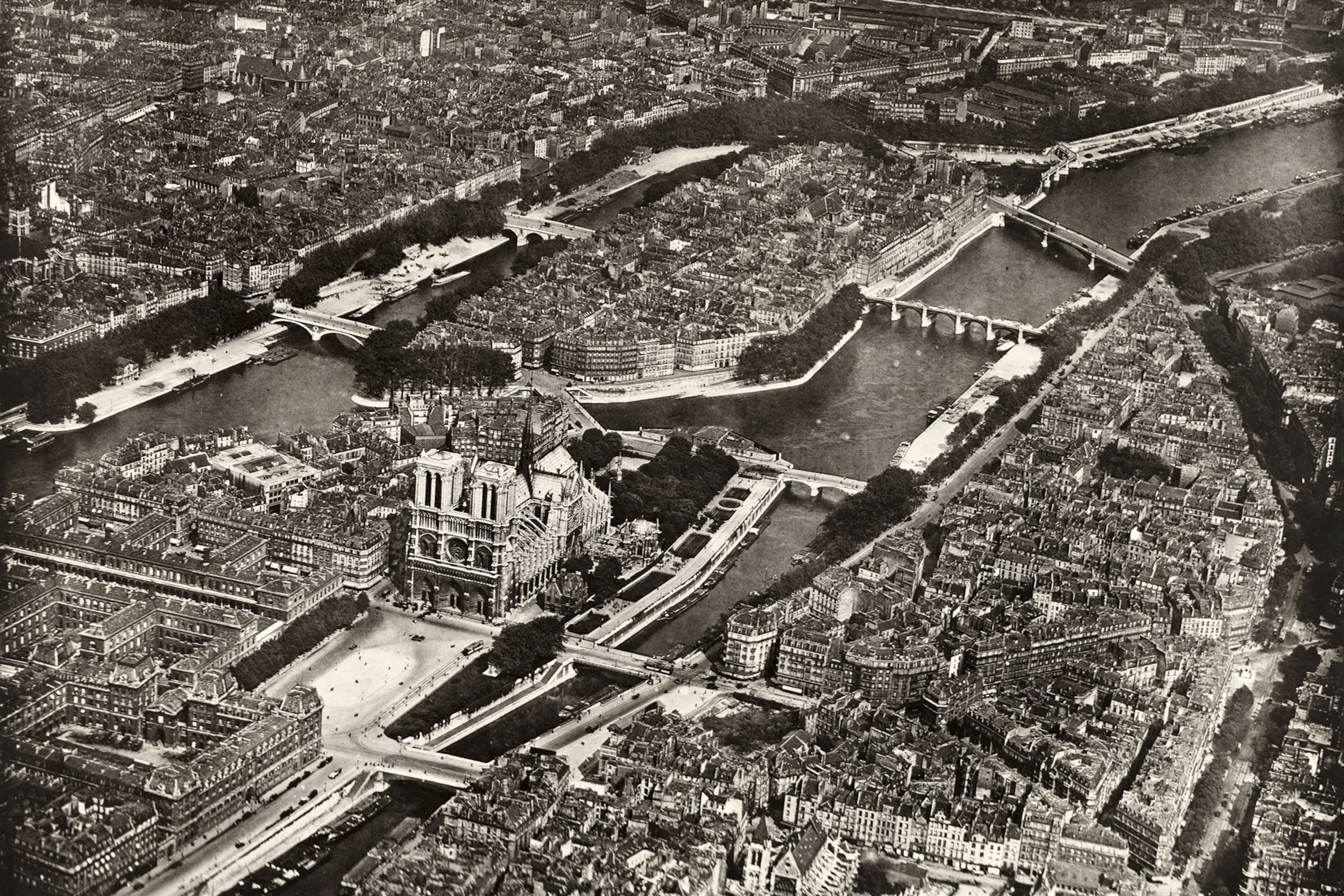

As France’s most famous cathedral burned, people around the world paused, horrified by footage of the catastrophic fire. Now they’re breathing a sigh of relief with news that firefighters managed to save much of Notre Dame de Paris from the flames.

But the fire has ignited a longstanding debate about how best to protect cultural heritage sites—places that too often lack adequate defenses against a range of disasters.

“Many World Heritage properties do not have any established policy, plan or process for reducing risks associated with disasters,” UNESCO writes. “As a result, hundreds of sites are critically exposed to potential hazards.”

Those hazards, which range from fire to flood, climate change to conflict, have wiped out many of the world’s cultural treasures in recent years.

Last year, Brazil’s National Museum was decimated in a fire, leaving artifacts such as the museum’s Egyptology collection and audio recordings of now-lost indigenous languages in ashes.

In 2016, Islamic State militants destroyed the Mashki and Adad Gates at the ancient site of Nineveh in Iraq. And the 2015 Nepal earthquake laid waste to culturally significant temples and other sites.

But cultural caretakers aren’t always eager to engage in disaster planning, says Jonathan Bell, director of the National Geographic Society’s Being Human Initiative. “It’s not a cheap undertaking,” he says, and local officials may feel pressure to maximize tourism dollars and minimize closures.

Collaboration between researchers, preservation experts, and local leaders is key, says Valéry Freland, director of ALIPH, a cultural heritage foundation that intervenes at sites threatened by conflict. “We must pay attention to the local situation and the real needs on the ground, and work with local actors.”

Restoration is risky business

Ironically, the Notre Dame fire occurred during a long overdue bid to save the cathedral from crumbling. But that comes as no surprise to experienced conservators. According to the Getty Conservation Institute, the majority of fires at cultural institutions occur during renovation or construction.

“Conservation and restoration work is really sensitive,” says Bell, an architectural conservator who advises local professionals at World Heritage sites. For example, restoration work can expose old materials to electrical wiring and other hazards.

Bell recalls visiting one historic site where he noticed a lightbulb charring the surface on which it had been placed—inches from a priceless wooden dome. “I’ve seen that kind of thing on many sites,” he says.

Something similar may have sparked the conflagration at Notre Dame. Despite its monumental stone masonry, the cathedral’s interior skeleton was made of trees felled in the 12th century. “The Forest,” as its 1,300-year-old roof structure was nicknamed, appears to be a complete loss. (Watch how one historian used lasers to digitally archive the cathedral's structure.)

Notre Dame’s rector told a local radio station that fire monitors check the wooden roof three times a day, the New York Times reports. He confirmed that there is a firefighter on site, though it’s unclear whether that person was present when the fire broke out, or whether a firefighter is on duty 24/7.

Will the lessons of the Notre Dame fire sink in at other heritage sites? At the Palace of Westminster, the seat of Britain’s government, the architects of a massive renovation will have the blaze in mind as they further modify the structure’s fire suppression systems.

“We stand ready to learn any lessons that emerge from the fire at Notre Dame to ensure we do everything possible to protect our people and buildings on the Parliamentary Estate,” a Parliamentary spokesperson told National Geographic.

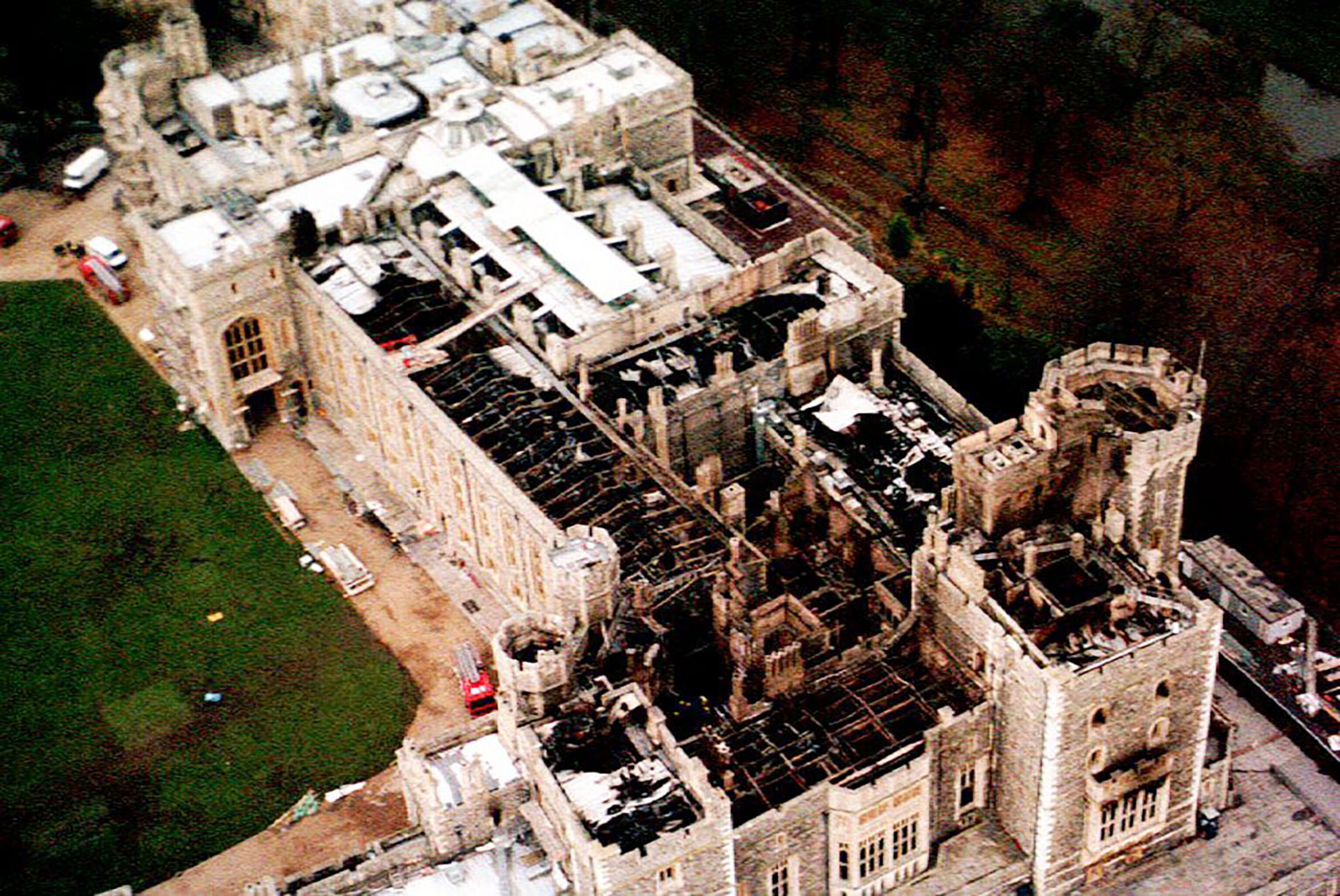

Officials at Windsor Castle, which was built around the same time as Notre Dame and which suffered its own catastrophic blaze in 1992, tell National Geographic that the structure is monitored around the clock for fire.

While other cultural heritage sites revisit their fire protection plans, officials must now decide how to repair Notre Dame. They’re getting support—and a big dose of hope—from craftspeople who helped another English landmark come back from the ashes almost four decades ago. (Discover why history says Notre Dame will rise again.)

In 1984, lightning sparked a catastrophic fire at York Minster, a Gothic cathedral built around the same time as Notre Dame. The church was restored with the help of craftspeople who used traditional materials to repair the cathedral’s damaged roof, stained glass, and other elements. John David, a York Minster master mason, told the BBC that restoring Notre Dame with traditional techniques is “quite achievable.”

Bell, who grew up in France, hopes those restoration plans include robust disaster preparation. “When you're working with a historic site, the value of that place is much greater than a typical building,” he says. And if the worst does happen, “It’s like losing an old friend.”