Visiting a U.S. national park—for the retro architecture

During the mid-20th century, the National Park Service launched the Mission 66 initiative: a bold plan to ditch rustic "Parkitecture" and go modern. It took decades for parkgoers to warm up to the audacious style.

In 1956, the National Park Service was in a pickle. The number of visitors to the parks had more than doubled in the prosperous decade since the end of World War II, and the parks were nowhere near ready for the surge. More than 50 million people came through the entrance stations that summer, most of them arriving in big old cars of post-war make, often pulling onto roads designed in the era of the Model T. Staffing shortages were rampant, and maintenance issues plagued the few rustic buildings that offered visitor services.

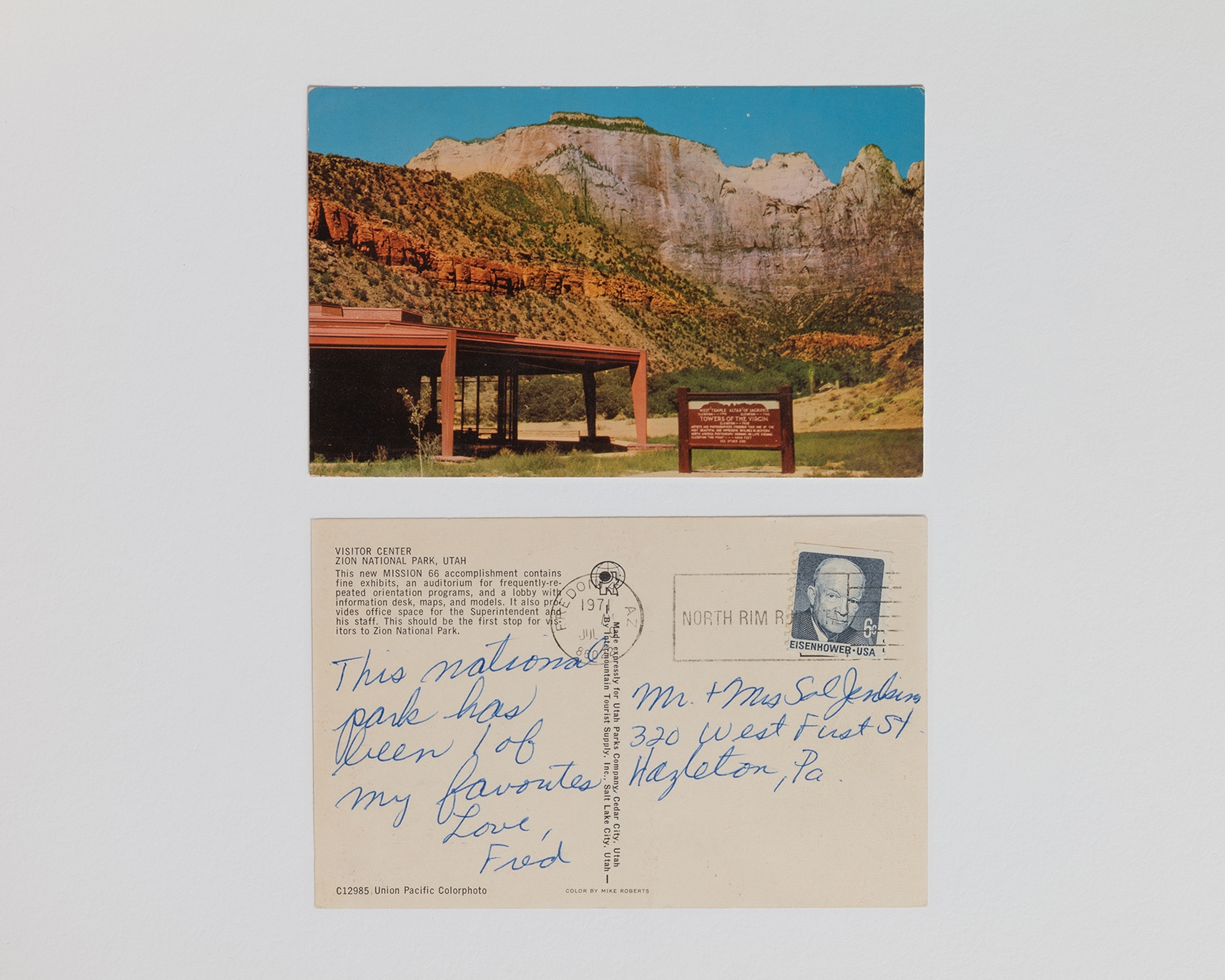

So the NPS set out to rescue the flailing parks with a 10-year, billion-dollar effort to modernize them. It was dubbed Mission 66—as in, revamp the visitor experience by 1966, the 50th anniversary of the park service. The effort saw the construction of centralized hospitality villages, what the NPS director at the time called “zones of civilization in a wilderness setting.” It introduced the then-novel concept of the visitor center, borrowing ideas from the shopping centers springing up around the burgeoning suburbs. And it brought mid-century-modern architecture to a park system where most buildings fell somewhere on a spectrum between ramshackle hunting cabins and Bavarian chalets.

Not every Mission 66 building was a showstopper—plenty were bland and functional ranger stations, admin buildings, or picnic shelters. But some were grand, architect-designed specimens of Jetsons-esque flair or Brutalist gravity. And right from the beginning—and for decades to come—they were debated, derided, and dismissed. “Ugly beyond words to describe,” wrote the traditionalist editor of National Parks magazine in the 1950s. “Some regrettable architectural legacies,” summed up a historian in the ’90s, at a time when calls to dismantle Mission 66 buildings were becoming commonplace.

But lately, defenders of Mission 66 architecture have seen a shift: What was once viewed as egregiously contemporary has come to be considered historic. What seemed out of step with the lodge-like style known as “Parkitecture” now seems nostalgic—even complementary. According to Ethan Carr, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the author of Mission 66: Modernism and the National Park Dilemma, people once associated modernist park architecture with the problems of modernity, like traffic and overcrowding—but less so as those have become mundane headaches.

“Nowadays,” Carr says wryly, “the whole American landscape is so devastated that people look at modernist architecture and think it’s quaint.”

The Cyclorama turning point

Architectural historian Christine Madrid French worked for the park service in the 1990s, at a time, she says, when Mission 66 buildings were often dismissed as eyesores. Many were overdue for repair, and the NPS’s mid-century tendency to site buildings right next to natural and historic resources had come to be viewed as intrusive. “At that point, most of these buildings built between ’56 and ’66 were not considered historic," says French, today the executive director of California’s Napa County Landmarks. “They were at a critical juncture: ‘Are they going to survive or not?’”

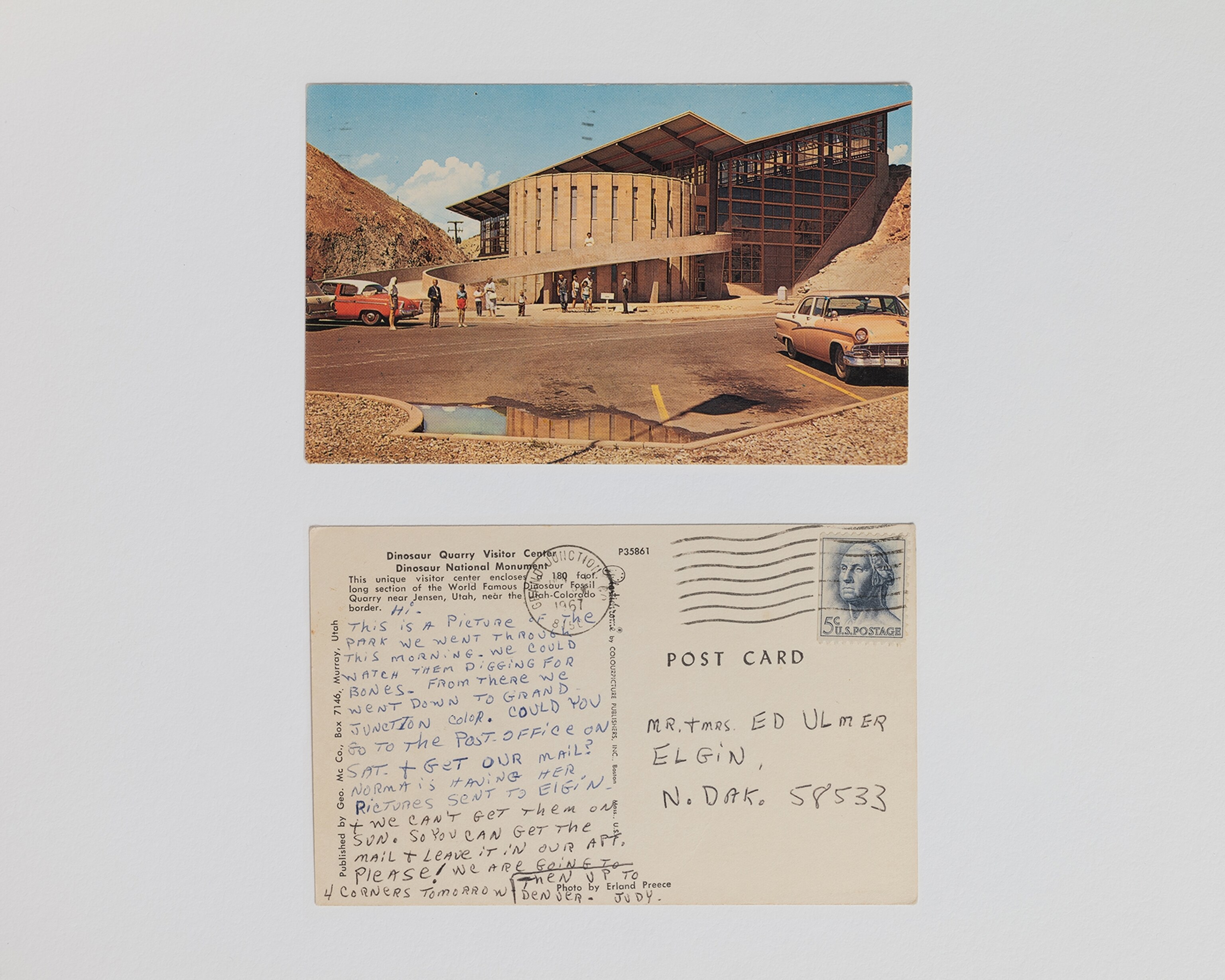

Some did not. A spate of Mission 66 demolitions in the 2000s included the Quarry Visitor Center at Utah’s Dinosaur National Monument, a squat and imposing concrete cylinder, and the Paradise Visitor Center at Washington’s Mount Ranier National Park, which was often compared to a flying saucer.

But the highest-profile wrecking ball swung in 2013, knocking down the drum-shaped, concrete-and-glass Cyclorama visitor center at Gettysburg National Military Park. Designed by influential modernist Richard Neutra, it was dedicated in 1962 right atop the site of Pickett’s Charge. Decades later, the NPS decided visitors would be better served with the hillside restored to something like its Civil War pastoral state. French led a legal and public-relations effort to save the Cyclorama, working together with the architect’s son, Dion Neutra, and a small but growing constituency of mid-century preservationists. But ultimately, it was to no avail.

“It was unpopular,” French says. “People just didn’t like it. They were like, what is that?”

The loss of the Cyclorama, however, seemed to kick off a reassessment of other Mission 66 structures. The very next year, the Neutra-designed Painted Desert Community Complex at Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park—itself briefly slated to be razed in the ’90s—was named a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. A collection of low-slung, glass-and-stucco buildings, it became a National Historic Landmark in 2017.

“What happened after the Cyclorama is that there was a change,” French says. “That was the big moment where everyone just said, ‘Stop, this is so cool! I want to see this stuff!’”

More than nostalgia

In the years since, French says, the prestige of mid-century design has only snowballed, and she credits everything from Mad Men to Palm Springs’ Modernism Week for Mission 66’s renewed cachet. These days, when a modernist park building has outlived its purpose, the conversation tends to be about adaptive reuse rather than demolition. Mid-century modern is the whole motif at Yellowstone’s Canyon Lodge, the first Mission 66 project to break ground, back in 1956. It was adapted beyond recognizability over the years but more recently restored to its Eisenhower-era glory, right down to the starburst chandeliers and egg chairs.

But Mission 66 was about far more than aesthetics, reminds Carr. It was a wholesale reimagining of how parks work in an era of auto tourism, carried out across the gamut of NPS properties—a level of top-down planning that’s perhaps rarer today, he suggests, when individual park initiatives and donor-led projects may play a bigger role in shaping infrastructure.

The planners and architects of Mission 66 “were really interested in this very specific visitor experience,” says preservation consultant Rebecca Zeller, whose Columbia University master’s thesis surveyed the state of the era’s visitor centers. And though she says it has sometimes been muddled by retrofits—gift shops and snack bars cluttering the intended flow—she praises the elegance of the buildings’ original purpose, guiding visitors through an almost choreographed routine of parking, welcome, and interpretation, all culminating in an appeal “to go out and explore the resource.” That final flourish was often a grand set of windows framing a park tableau—an invitation to leave the visitor center behind.

Kathryn O’Shea-Evans is the author, with Max Humphrey, of Lodge: An Indoorsy Tour of America's National Parks.