Amid the periods of turmoil in the history of the Roman Empire came the era of the Five Good Emperors. Instead of selection by dynastic succession, these five rulers were chosen and trained by their predecessors to ensure smooth, peaceful transitions of power. Among the five, Emperor Trajan (reigned 98–117 AD) acquired the title Optimus, or “best.” It was Trajan who not only expanded the borders of the Roman Empire to their greatest extent but also governed with singular benevolence and generosity toward his subjects.

Trajan’s selection as emperor by Nerva set an important precedent for Rome’s rulers. A military commander with Spanish roots, Trajan was the first emperor born outside Italy. The message of his elevation was clear: Qualified, educated men from throughout the empire could aspire to the highest office of the land.

Military might

Trajan extended the empire’s reach in Mesopotamia as far as the Persian Gulf, but he’s better remembered for his campaign against the Dacians. From their realm in modern-day Romania, the Dacians frequently raided Roman frontier towns. Trajan ended a two-year incursion into Dacia in 103 A.D. by signing a peace treaty with Decebalus, the Dacian king. Unwisely, however, the Dacians soon broke the treaty.

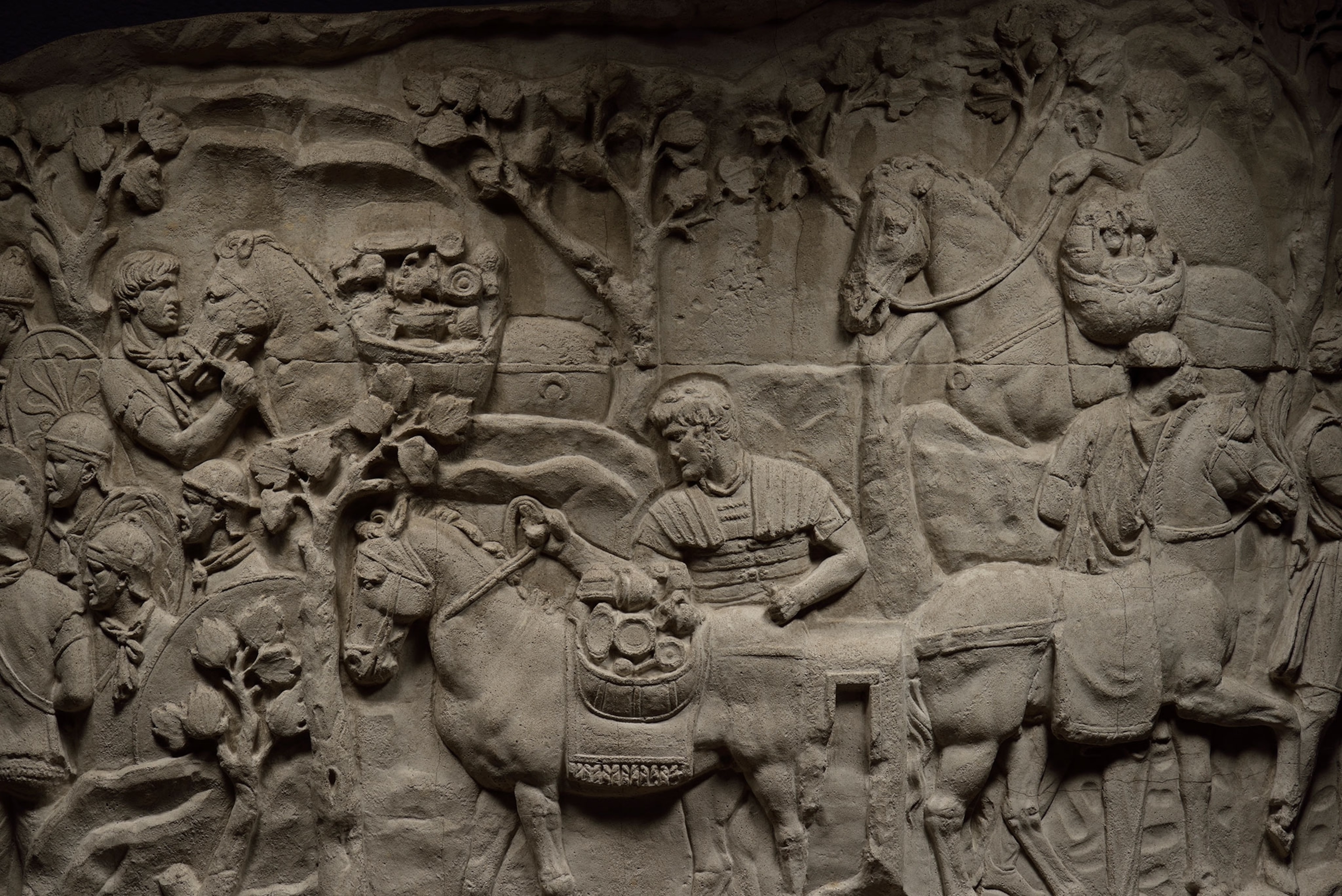

When Trajan returned to Dacia in 105 A.D., he showed no mercy. The devastation wrought by the Romans is depicted in elaborate carvings on the 126-foot-tall Trajan’s Column in Rome. A quarter of the column’s 155 scenes portray the battle: villages in flames, Roman soldiers holding the decapitated heads of the vanquished. When Dacia finally fell, Trajan took home an astounding bounty, estimated by one contemporary account to be half a million pounds of gold and a million pounds of silver. (Take an interactive tour of Trajan's Column.)

Trajan put the proceeds from the Dacian War to good use throughout the empire. He built roads, bridges, aqueducts, and harbors from Spain to the Balkans to North Africa. In Rome itself, a new aqueduct supplied the city with water from the north. Trajan’s Column towered over a magnificent new forum, which boasted two libraries, a grand civic space, and a colonnaded plaza.

Showing tremendous generosity to the Roman people, particularly in areas of social welfare, Trajan increased the amount of grain handed out to poor citizens and doled out cash gifts as well. He allowed provinces to keep gold remittances that would normally be sent to the emperor and reduced taxes. Trajan emulated his friend the historian Pliny the Younger by expanding public funds, called alimenta, to care for poor children.

In fact, it was Pliny himself who best captured the sum of Trajan’s reign in one of his many letters to the emperor: “May you then, and the world through your means, enjoy every prosperity worthy of your reign.” (Discover the story behind Trajan's ruins.)

Recording history

Much of what historians know about Rome in the time of Emperor Trajan is due to Pliny the Younger—Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (ca 61–113 A.D.). A noted orator, senator, and administrator, Pliny wrote ten books of letters that combined philosophy, history, and poetry. They expounded on matters ranging from his domestic life to senatorial debates. (Follow the hunt for missing Dacian treasure.)

He developed his epistolary under the tutelage of his uncle and honorary name-sake, Pliny the Elder, a scholar who wrote the encyclopedic Natural History. In 79 A.D., the younger Pliny witnessed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, with its “dense black cloud ... spreading over the earth like a flood.” Sadly, his uncle perished in the eruption. Pliny the Younger’s description of the event appears in one of his most famous letters.