The Roman emperor who died from eating too much cheese

Lots of emperors met ignominious ends. And then there was Antoninus Pius.

The Roman Empire conjures up images of military power, gladiatorial contests, and feats of engineering, but to the men who ruled, life was complicated and fraught with risk.

Julius Caesar, whose power grabs laid the groundwork for the first Emperor Augustus’s ascent, was not the only would-be tyrant to die violently: some emperors ruled for just a few weeks, while others met sticky ends at the hands of trusted bodyguards and family members. For those who survived, their imperial status gave them the opportunity to indulge their whims and flex their muscles—and their obsessions were often strange indeed. From exiling their own children to introducing a tax on urine, the emperors of Rome made the most of their unfettered control. Here are some of the most ambitious, bizarre, and egotistical projects they embarked upon—and some of the most uncomfortable ways they ended their rule.

Augustus banished his own daughter

In 18 BCE, the Emperor Augustus passed a sweeping set of moral reforms known as the Julian Laws, which sought to revive traditional Roman virtue by rewarding marriage and punishing adultery. For the first time in Roman history, infidelity became a public crime rather than a private scandal—one that carried the penalties of exile and property confiscation. The laws were meant to model civic discipline, but their most famous victim was Augustus’s own daughter, Julia, whose glamorous and notoriously unrestrained social life soon became a public embarrassment. Ancient writers such as Suetonius, Cassius Dio, and Velleius Paterculus report that when Julia was found guilty of adultery, her father exiled her to the desolate island of Pandateria (modern Ventotene). According to Suetonius, she remained there for five years before Augustus allowed her to return to the mainland. He never recalled her from exile, however, and felt humiliated by her behavior. When one of Julia’s confidantes, a former enslaved woman named Phoebe, hanged herself around the same time, Augustus is said to have remarked, “I would rather have been Phoebe’s father.”

Even if Julia was the most harshly treated, Augustus’s desire to control and shape his family members did not stop there. According to Suetonius, who wrote his biography of the twelve Caesars roughly a century after Augustus’s death, the emperor had a very particular handwriting style. It was so distinctive that Augustus insisted upon teaching his heirs how to write in the same style, training them “to imitate his handwriting.” This kind of “scriptory micromanagement,” writes Australia National University Professor of Classics Tom Geue, “is unique to Augustus” and offers evidence of an almost obsessive desire to secure his legacy by replicating himself in his successors.

Claudius tried to change the alphabet

As with Augustus’ laws of virtue, the emperor Claudius (41-54 CE) also wanted to change the fundamentals of Roman society. According to Suetonius, he attempted to add new letters to the Latin alphabet: the antisigma Ↄ which sounded like a bs or ps; Ⱶ, a half H which seems to have been a short vowel sound; and the digamma Ⅎ that sounded like a “w.” Suetonius adds that Claudius even wrote a book to explain the theory behind them.

Though this may seem audacious, ancient languages did evolve and change. It was that practice, the historian Tacitus writes, that led Claudius to attempt this shift. Tacitus remarks that it was once Claudius “discovered that not even Greek writing was begun and completed at one time” that he decided to design “some additional Latin characters.” In her book Empire of Letters, MIT professor Stephanie Frampton explains that Claudius’s introduction of new letters was seen as part of a tradition whereby language and the alphabet developed over time.

Though examples of the Claudian letters have been found in archeological discoveries, the endeavor was effectively a failure. Suetonius notes that the letters quickly fell out of use. Even the emperor of Rome couldn’t change how people wrote.

(The most expensive mistake in ancient Roman history.)

Nero forced people to listen to him perform

If Augustus was focused on managing his household and the empire, the Emperor Nero, who ruled from 54-68 CE, was more interested in entertaining and performance. Destined for a life in politics, Nero longed instead to tread the boards of the stage. In addition to writing poetry and appearing in chariot races, he regularly forced his subjects to attend his musical recitals. According to Suetonius, “while he was singing, no one was allowed to leave the theater even for the most urgent reasons.” Suetonius adds that pregnant women went into labor and delivered infants while he was performing. Others, fatigued from applauding his efforts, attempted to escape the locked gates which held them as a literal captive audience, risking injury by jumping from the walls of the theater. The particularly desperate, wrote Suetonius, feigned death so that they might be carried out for burial. The story is likely exaggerated, but makes for juicy gossip nonetheless.

Many other stories around Nero, however, are rather less charming: his relationships with the women in his life were tinged with violence. When he tired of his controlling mother Agrippina’s political interventions, he plotted her death. After several failed poisoning attempts, he orchestrated a shipwreck that she managed to survive by swimming to shore. When news of her survival reached the emperor, he finally had her stabbed and claimed that she committed suicide.

After Agrippina’s death, Nero’s behavior grew increasingly bloodthirsty. After divorcing and exiling his wife Octavia, he accused her of adultery and had her executed. Suetonius claims that he kicked his second wife, Poppaea, to death while she was pregnant with his child. Like many of Suetonius’s stories, this may have been invented to exaggerate Nero’s cruelty.

Nero’s willingness to discard those close to him extended to his neighbors in the city of Rome. Many ancient historians accuse Nero of starting the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE in order to clear the ground for his extravagant building projects. Cassius Dio writes that, as the fire burned, he climbed to the roof of his palace dressed as a lyre-player, and sang the song “The Capture of Rome.” This likely false detail is the origin of the myth that Nero fiddled while Rome burned, but it cements his reputation as an obsessive musician.

(Did Romulus and Remus really build Rome?)

Vespasian had an unsavory past

Vespasian (69 -79 CE) brought stability to the Roman empire after a year of chaotic civil war following the death of Nero, but his background was suspect: the founder of the Flavian dynasty, who is best known for conquering most of Judea during the First Jewish War, may have made his initial fortune as a slave trader specializing in castrati or eunuchs.

Around 62 CE, the future emperor finished his term as proconsul of Africa in financial trouble. His credit was ruined, and he mortgaged his property to his brother. He turned then to commerce of the most dubious sort. Suetonius writes that Vespasian was a “mango” (a kind of ne’er-do-well merchant) who dealt in “mules.” In 2002, A. B. Bosworth published a convincing argument in Classical Quarterly that the term mulio (mule) was used to refer to those who traded in human beings and that the “mules” in question were not donkeys but young boys who had been enslaved and forcibly castrated. Eunuchs were a valuable commodity in the Roman slave trade, and if Vespasian was engaged in this kind of business, it would explain how he restored his fortunes so swiftly.

Even once he became emperor, Vespasian was not averse to profiting from taboo industries. Sarah E. Bond, associate professor of ancient history at the University of Iowa, said that when the frugal Vespasian became emperor, he inherited an empire “in dire financial straits.” As part of his austerity measures, he reintroduced a tax on urine (vectigal urinae), an important product in the laundering and tanning industries of Ancient Rome. “The urine,” said Bond “came from public latrines and from ceramic chamber pots emptied out into the streets from the apartments above.” We don’t know exactly how much money was made, she added, but “in a city of 1 million” there would have been “hundreds of tanners [and fullers]” who “would have needed to use these human waste products for their businesses.” The tax must have generated a sizeable sum for Vespasian.

Both Suetonius and Cassius Dio write that when Vespasian’s son, Titus, found the whole enterprise quite unbecoming of their status and expressed his revulsion, Vespasian held up a gold coin and asked Titus if they had any stench. This anecdote is the origin of the expression “money doesn’t stink.”

(Quiz: How much do you know about the Roman Empire?)

Antoninus Pius died of a cheese overdose

Not all imperial quirks are so unrelatable. Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE) was something of a homebody who enjoyed cheese. Mild-mannered and eminently capable, he is known to later historians as one of the “good emperors” since he guided Rome through a relatively peaceful 23-year reign. Unfortunately, his love of dairy proved to be his undoing. According to the Historia Augusta, a fourth-century biographical collection, “he died of a fever which he brought upon himself by eating Alpine cheese too greedily. After taking a bath on the third day [of his fever], he lay down, summoned his friends, and gave orders that Marcus [Aurelius] should be commended to the soldiers as emperor. Then, as if in sleep, he passed away.” The Historia Augusta is our lone source for this tidbit and is known for being historically unreliable. Nevertheless, if true, Antoninus’ death was one of the more sympathetic among the Roman rulers.

(Life on the Roman frontier revealed by soldiers' letters.)

Valerian ended his life as a footstool

Other Roman emperors met far more bloody ends than the cheese-loving Antoninus. Nero committed suicide; Galba was murdered by his bodyguards, the praetorians; and Geta was murdered by his brother Caracalla—with his mother’s assistance. Arguably the most degrading end fell to Valerian, who ruled in the middle of the third century CE.

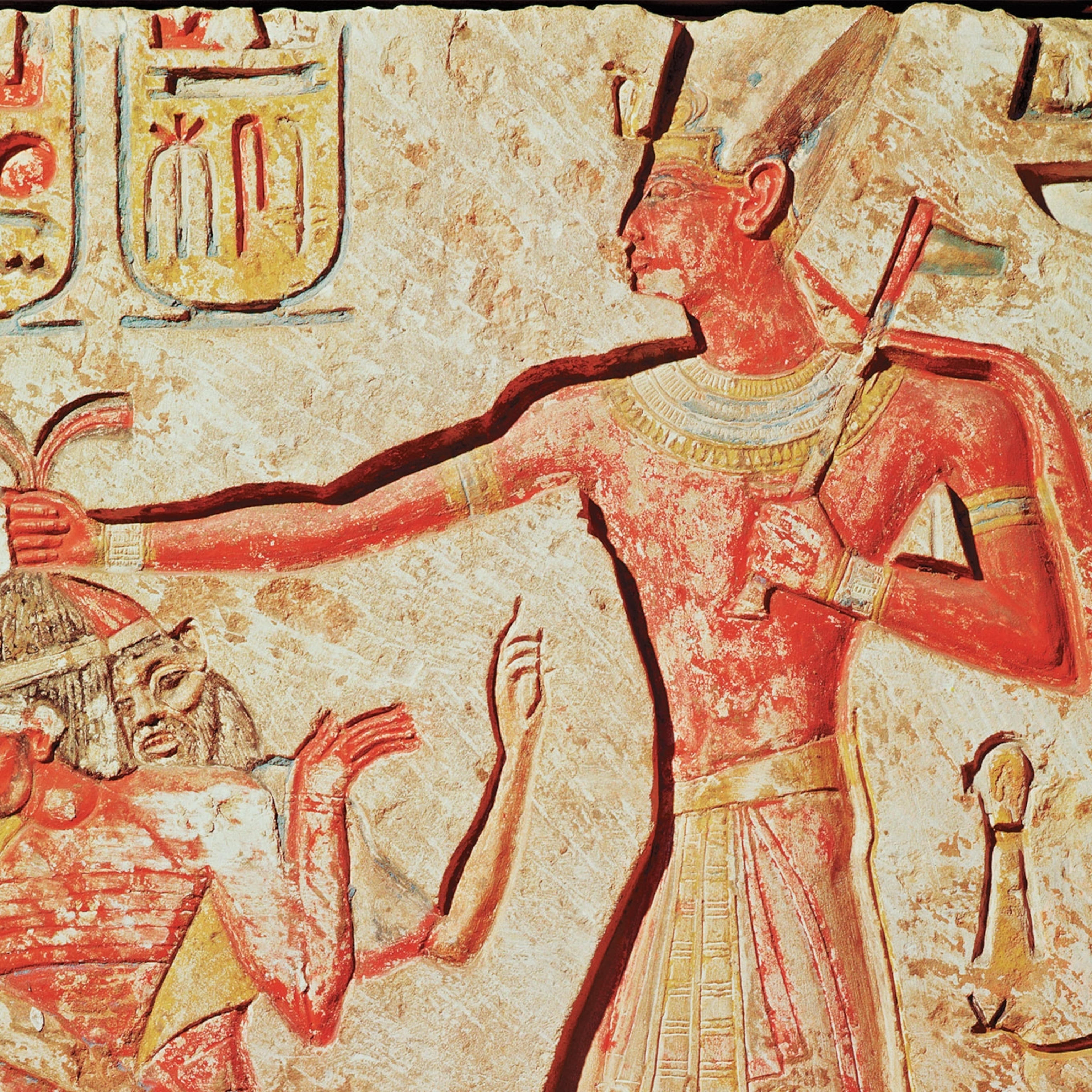

Valerian spent most of his career fighting the Persians on the eastern frontier, where he was eventually captured by King Shapur I. Shapur proved to be a cruel victor. Having taken Valerian prisoner, he kept the fallen emperor alive as a trophy and delighted in regularly humiliating him. According to the fourth-century writer Lactantius, whenever “Shapur wished to mount his horse or chariot, Valerian was made to offer his back, and the king placed his foot on the Roman emperor as a step.” After a long period as a human footstool, writes Lactantius, Valerian was turned into a macabre scarecrow. He was “finally flayed alive, and his skin, filled with straw and dyed red, was displayed in a Persian temple as a perpetual memorial of the king’s victory.” To be sure, the historical accuracy of this story is debated. It comes from the sensational On the Deaths of the Persecutors by Lactantius, a Christian author who despised Valerian’s mistreatment of Christians. While other historical sources describe Valerian’s capture and mockery by the Persians, and a relief at Naqsh-e-Rustam in modern-day Iran depicts him in captivity, no other references to his flaying have survived.