For youth in war-torn nations, education suffers profoundly. Schools are destroyed by indiscriminate shelling or deliberately turned into military posts. Children and teachers stay at home, afraid to step on a landmine or be caught in the crossfire of warring parties. The house of learning, envisioned as a safe haven, becomes a target.

For nearly a decade, photographer Diego Ibarra Sánchez has examined how conflict interrupts, interferes with, and obstructs learning. “Education is supposed to be the way forward, the way to build or rebuild a nation,” he observes. What happens to that goal when academic institutions can’t play their part?

After exploring that question in Pakistan, Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Colombia, Ibarra Sánchez turned to the Donbass region of Eastern Ukraine. Since 2014, fighting there between Kremlin-back separatists and pro-Ukrainian government forces has exacerbated nationalist sentiment—and sown chaos for education systems and their students.

When they miss months, even years of classes, students fall further and further behind and jeopardize their future, Ibarra Sánchez says. But when students do get schooling in war zones, they may find that curriculums have been co-opted, the teachings transformed to reflect the intentions of the faction in power.

In Donbass, Ibarra Sánchez says, the patriotic youth organizations he documented actively train children not only how to survive combat and handle weapons, but also “how to hate ‘the other,’ how to defend yourself against your neighbor and kill them if necessary for your country.”

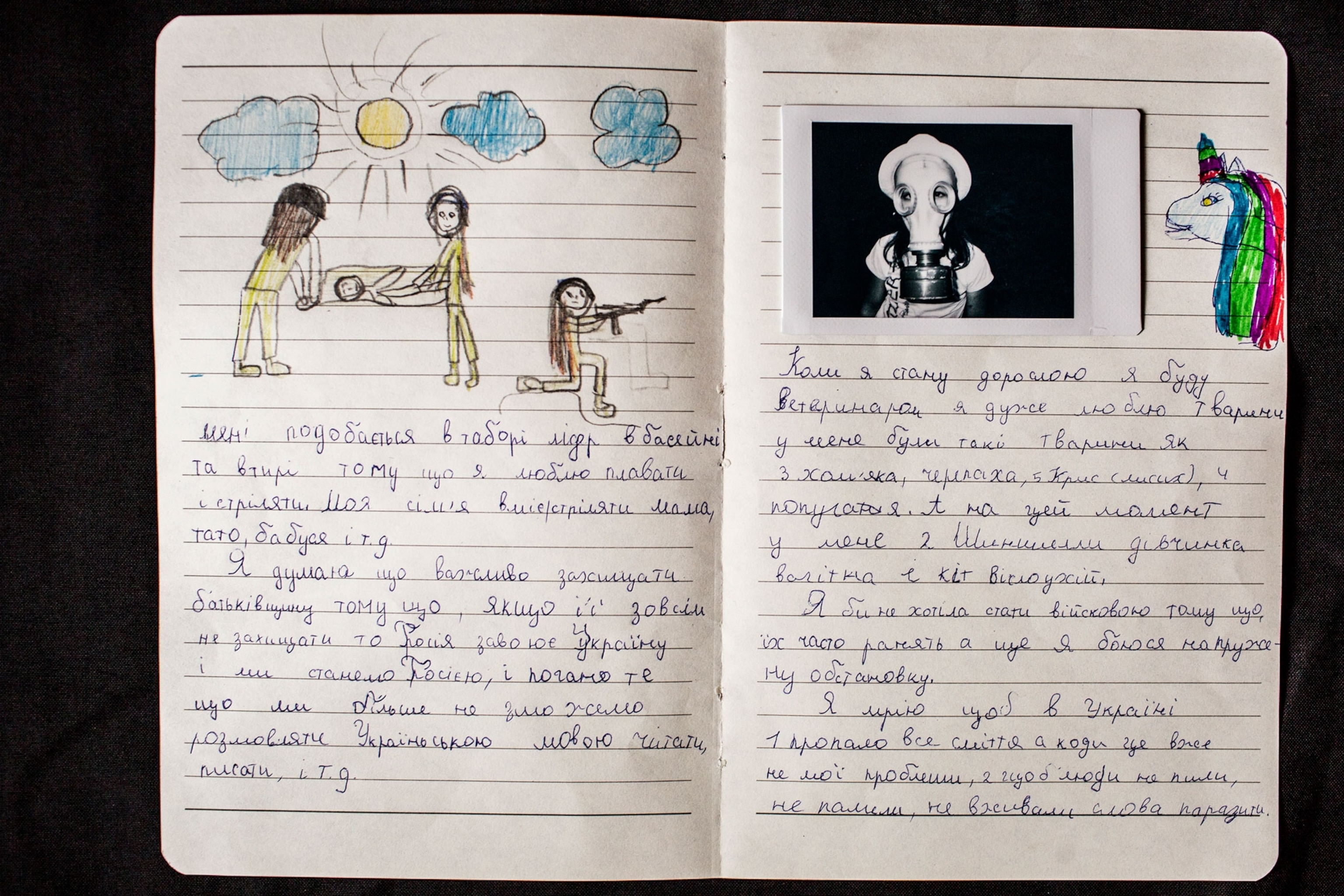

At LIDER, a summer camp for children age 6 to 17 in the outskirts of the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, youngsters wake up and listen to the national anthem during a flag raising ceremony, before taking part in various military training exercises. They learn how to crawl through trenches, how to put on gas masks, how to assemble and disassemble assault rifles, how to shoot, and more. The whole time, Ibarra Sánchez says, they are listening to anti-Russia and survivalist rhetoric. (Learn how boys from Ukraine and around the world become men.)

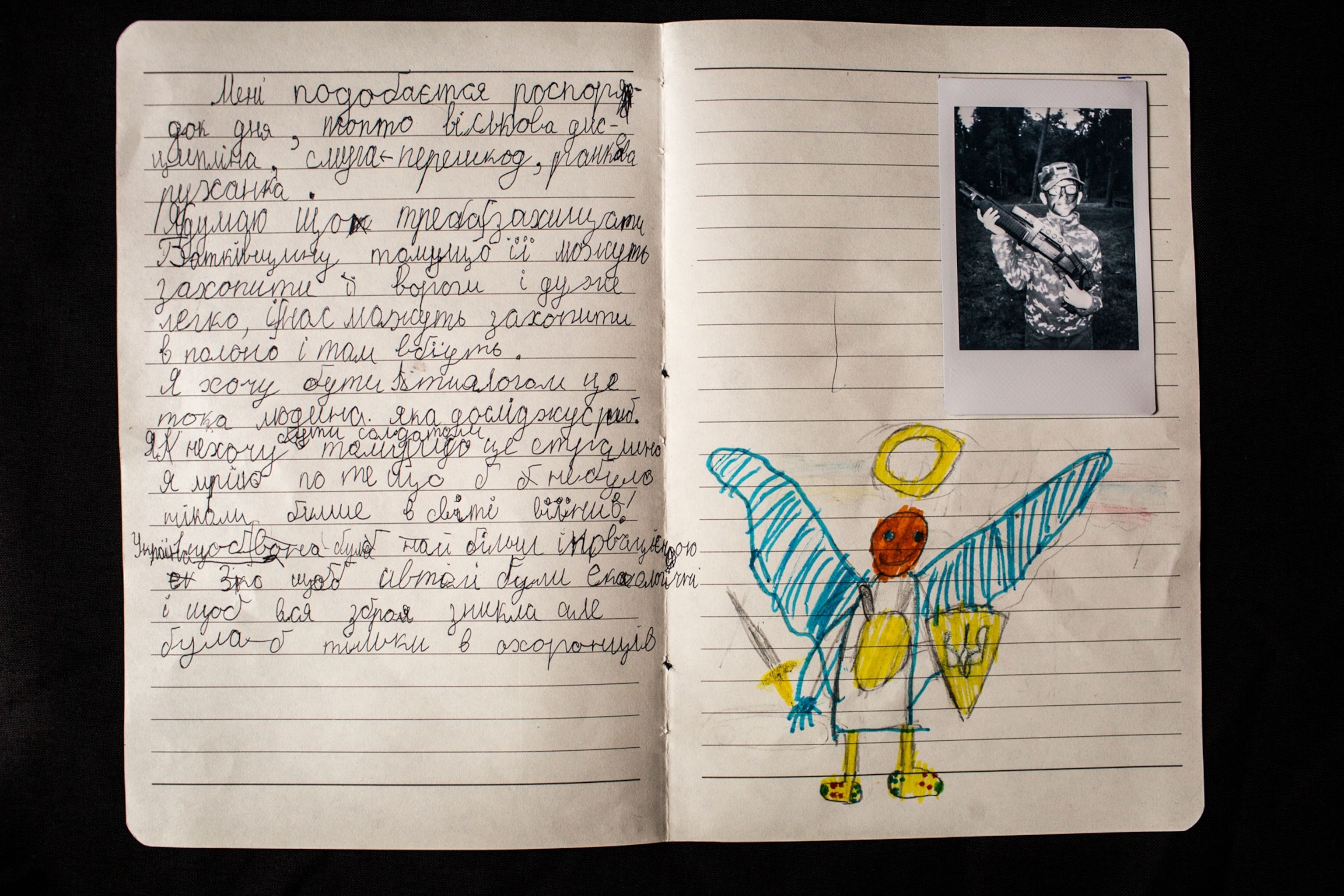

During his time at LIDER, the photographer asked the youngsters to answer three questions by writing and drawing in a notebook: why are they at the camp, why do they want to protect their country, and what are their dreams. Their answers reflect conflicting influences: the indoctrination at the camp, their understanding of the realities of war, and also their youthfulness and desire for a normal childhood. (See how students in Kiev celebrate the end of the school year.)

In her notebook entry, Yelena Shevel, 10, reported that she likes going to the swimming pool and the shooting range equally. Mykhailo Deinikov, 8, wrote that he believes “it’s important to defend the homeland because it can be captured by the enemy very easily and we can be taken hostage and killed.” Yet he also wrote about his peacetime dream of becoming a fish researcher: “I do not want to become a soldier because it’s scary. I dream that there will be no more wars in the world.”

On the other side of the frontline in this conflict, military academies are encouraging cadets to join the Kremlin-backed separatist armed forces. It’s been reported that the G.T. Beregovoj Military Lyceum in the Donetsk People’s Republic—the separatists’ self-proclaimed state in Eastern Ukraine—has graduated more than 300 students since the war began in 2014. There too, Ibarra Sánchez says, there’s a relentless emphasis on demonizing the foe: “Having an enemy is a powerful way to reinforce the idea of a nation with a common goal.”

Since 2014, more than 10,000 lives have been lost in Eastern Ukraine, according to UN estimates. To Ibarra Sánchez, the conflict—and the way that youth are being recruited to it—isn’t really about patriotism. “Love for the homeland is when your heart is at peace,” he says. “When you try to impose your ideas on someone else, when you think you’re superior to others—that your flag, your history, your politics, your values are better—that’s when it gets dangerous.”

_4x3.jpg)