Searching for life across the planet’s frigid frontiers

In order to understand the massive changes afoot in the warming polar regions, oceanographer Allison Fong is hunting for the tiniest clues.

The northern and southern reaches of our planet are heating up faster than anywhere else on Earth. While researchers already know that the region is poised to change dramatically—with ice melting and sea levels rising—there’s a larger question of just what species may survive under those new conditions. Which is how microbial oceanographer and National Geographic Explorer Allison Fong found herself wearing a dry suit and 80 pounds of scuba gear underneath a 26-foot-thick ice floe in the Arctic Ocean, clutching a glorified turkey baster.

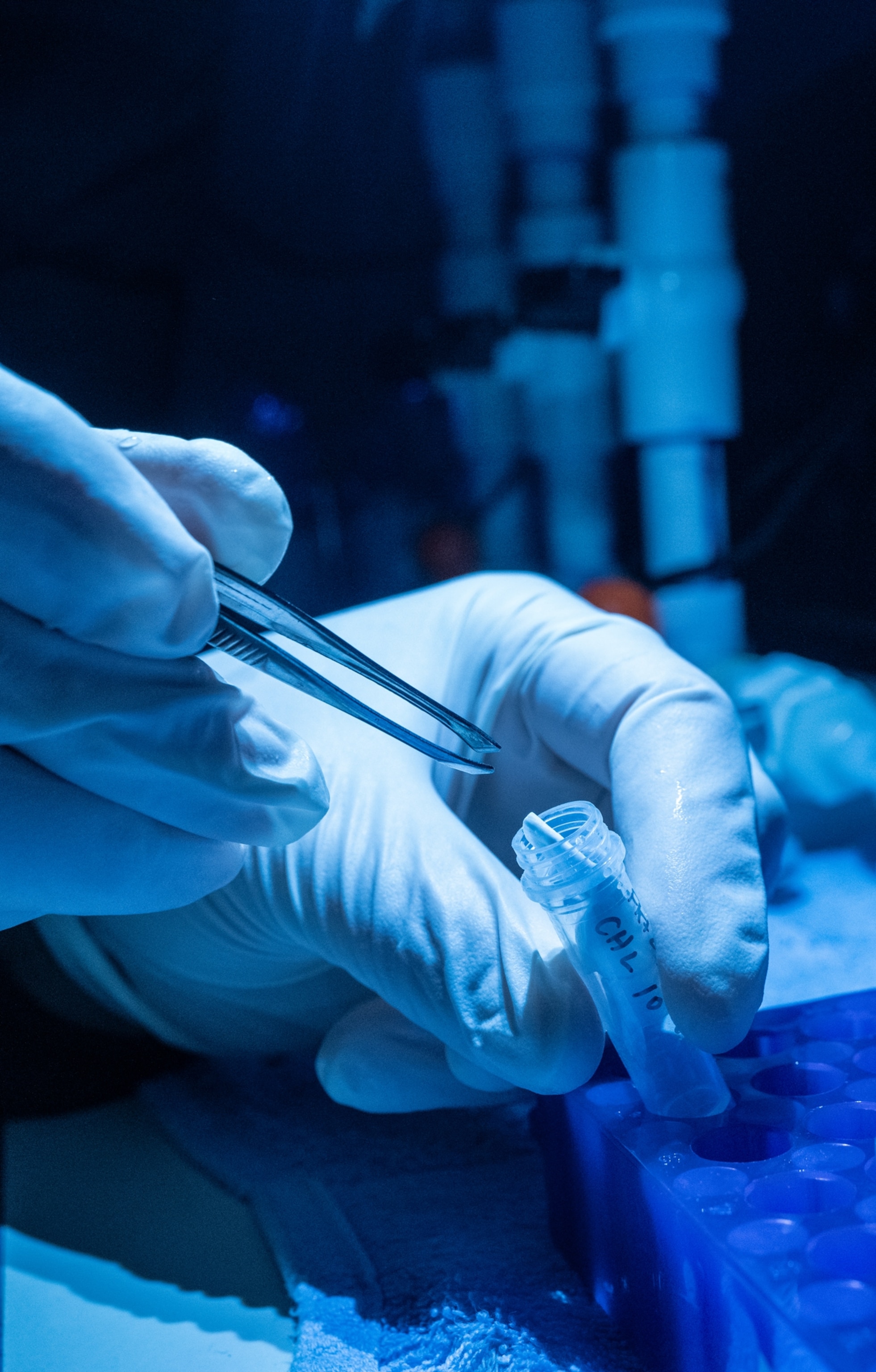

Fong was using the enormous syringe to slurp up a thin film of tiny organisms living in the floe’s underbelly. These microbes, like photosynthetic phytoplankton and sea ice algae, are “fundamental to the habitability of Earth,” she says. By studying them, we can understand how ecosystems are thriving—or not—and how different parts of the planet will transform as climate change accelerates.

In polar food webs, microbes capture energy from the sun and become nutrients for all the animals above them in the food chain. But unlike larger creatures like polar bears and whales, microbes have short lifespans, sometimes as brief as a few days, making them much more responsive to what’s happening in their environments. In the past six years, Fong has measured oxygen concentrations in microbial communities found in sea ice at both poles to assess what biologists call productivity, which is a measure of food availability in an environment. Her research could provide a window into the types of species that are able to flourish and those that may flounder.

Take the Pacific cod. Currently, there are hardly any of these fish in the high Arctic, because there isn’t enough available food. But as sea ice decreases, more sunlight will reach the water. In turn, some scientists expect the microbe population to grow, providing nutrients at the base of the food chain, thereby allowing the fish to migrate and making the far north and south a potentially lucrative opportunity. One report from the Fisheries Economics Research Unit at the University of British Columbia projects total fisheries revenue in the Arctic may increase as much as 39 percent by 2050.

But commercially exploiting the waters of the Arctic would have huge implications for both the ecosystem and the Indigenous communities that rely on marine life to support their subsistence livelihoods. Experts warn that models predicting new fish stocks are extrapolating too much from a small amount of available information. After all, the Arctic is a massive area, where few people have collected reliable data.

Fong is well aware of how her measurements may be construed. “People could look at our data at the base of the food web and then make a couple of leaps,” she says. One minute you’re measuring microbes; the next, a government department is saying the poles are ripe for the picking.

From Fong’s perspective, that makes capturing the most complete picture of how the region is changing ever more urgent. “When we lose sea ice from our polar regions,” she says, “we are altering the landscape of what can and cannot exist.”