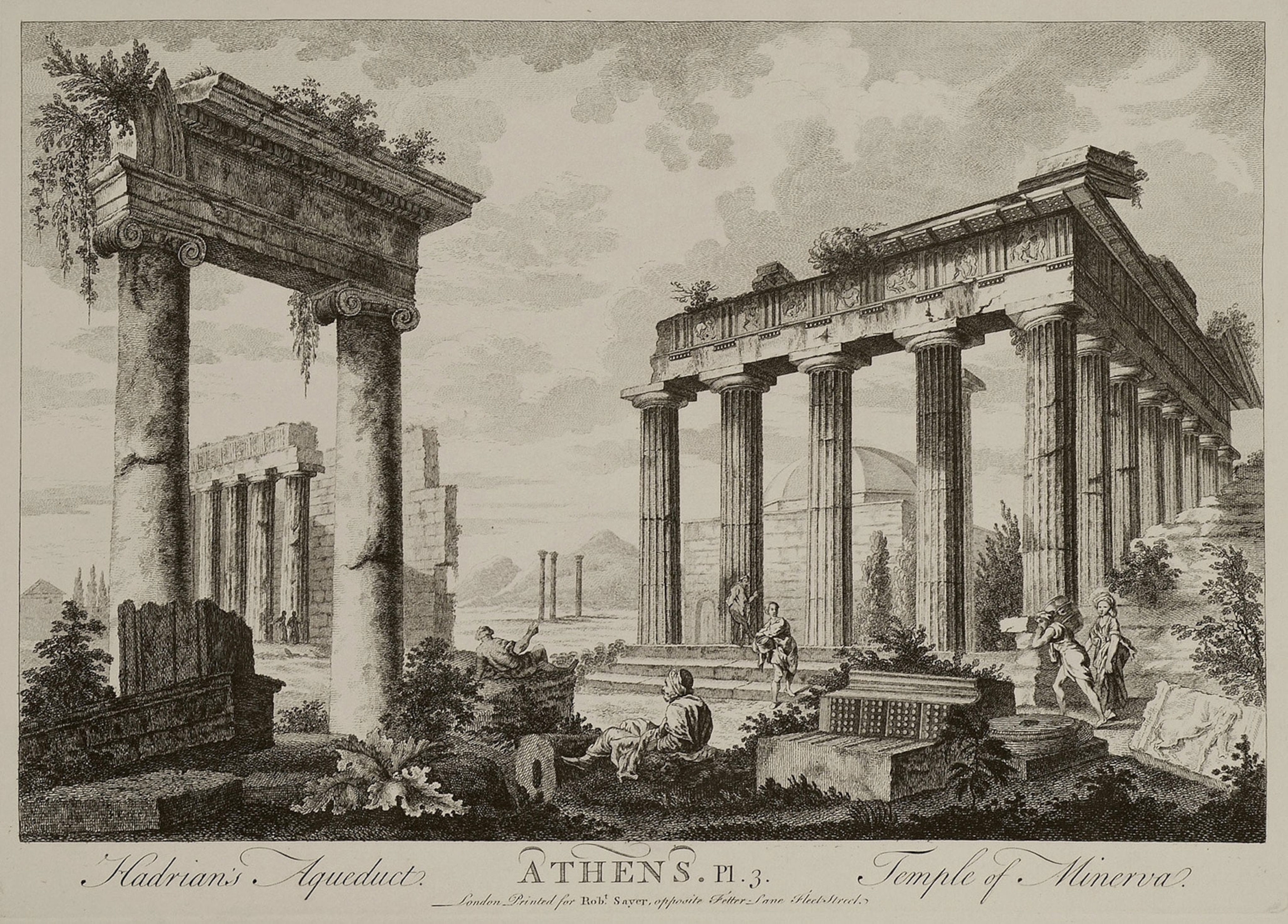

Athens is reviving a 2,000-year-old Roman aqueduct: 'the miracle is that it still works'

Engineers believe Hadrian’s Aqueduct, which was constructed in the second century, can help the city conserve dwindling water supplies amid worsening droughts.

Athens, Greece — When Eleni Sotiriou and her neighbors turn on their taps in the coming weeks, they’ll be getting water from an ancient aqueduct connected to a bygone, underground waterway that many Athenians are unaware exists.

“It’s very exciting that something built 2,000 years ago will be used by modern Greeks for such an important reason,” said Sotiriou, an environmentally conscious 65-year-old who admonishes neighbors for wasting dwindling drinking water on activities such as washing their cars. “We have to be careful,” she said. “There isn’t an unlimited supply.”

Sitting on Europe’s sweltering southeastern border, Greece has been hard hit by a water crisis worsened by climate change. Last year, an acute shortage of rainfall prompted several Greek islands to ration water as farmers struggled to produce crops. Growing tourist numbers increased the strain on water. So did rising temperatures, stoking wildfires that intensified dry conditions.

In Athens, where water levels are the lowest in a decade, authorities plan to link the main reservoir to an artificial lake and are modernizing the water network to plug leaks while developing sustainable ways to recycle wastewater.

The most innovative response, however, relies more on ancient inventiveness than modern technology: tapping into an aqueduct built at the height of the Roman Empire.

Indeed, after a project five years in the making launches in July, scores of homes in one Athens suburb will gradually be drawing water directly from the ancient pipeline in an experiment aimed at saving water and cooling the city. The water won’t be potable, but officials hope it will conserve drinking water by supplying another source of water for uses like gardening.

"The miracle is that it still works,” said Giorgos Sachinis, director of strategy and innovation at the Athens Water Supply and Sewerage Company, adding that Roman hydraulic engineering is “truly admirable.”

Connecting the past to the present

Commissioned in the second century A.D. by Roman Emperor Hadrian to satisfy the growing demand for water in Athens—one major use being the public baths favored by Romans—the 15-mile aqueduct was “a grandiose” project, longer and more sophisticated than previous waterways, according to Theodora Tzeferi, an archaeologist at Greece’s Culture Ministry.

(The most expensive mistake in ancient Roman history)

It supplied Athens for more than 1,300 years before falling into disrepair during the Ottoman occupation of the Greek capital, which began in the mid-15th century and lasted for nearly 400 years. The aqueduct was revived in the late 19th century amid a water shortage and then largely abandoned in the 1920s when the capital’s first reservoir was built to serve growing demand.

But the water never stopped running. Hadrian’s Aqueduct still flows beneath the capital, from a mountain north of the city to central Athens. As the aqueduct runs downhill, it’s filled by aquifers and riverbanks.

It is the only ancient monument in Greece that has operated for so long, according to Tzeferi. She’s overseeing the project, which received structural damage during past construction on the city’s metro system.

Talk to Athenians in a café near the central reservoir and most are unaware of the aqueduct beneath them. “They don’t know about it as you can’t see it,” Tzeferi said.

Currently the water is wasted, joining the sewage system and then the sea. A new two-and-a-half-mile pipeline has been built to connect the aqueduct to households in Halandri, the suburb where the initiative is being tested.

“It’s quite simple. We pull the water out of a Roman well, we process and filter it in a modern unit next to the ancient one, and from there it goes to homes,” Sachinis said.

The pipeline will first supply civic buildings and then around 80 houses with non-potable water for cleaning and gardening, allowing them to conserve drinking water while using digital meters to monitor what they use from the aqueduct. Buildings closest to the pipeline will each be connected via an outdoor tap with dozens more getting their water by truck.

The aim is to expand supply to another seven districts under which the aqueduct runs.

A model for other parched cities?

Project managers concede that anticipated water savings are small—one percent of the 100 billion gallons of water used annually in Athens—but their focus is on creating a new “water culture” of cautious consumption.

Using tap water to cool sidewalks in summer, for instance, is “criminal,” Sachinis remarked.

Experts say this cautious consumption is crucial.

“I’m worried we’re heading towards a semi-arid climate,” said Eleni Myrivili, a senior advisor for the Washington, D.C.-based Climate Resilience Center at the Atlantic Council, referring to her native Greece.

“Hadrian’s Aqueduct is a brilliant way of creating resilience,” said Myrivili who also holds the title of global chief heat officer for the United Nations Environment Program and its Human Settlements Program. She recently co-authored a report with proposals for using water from the aqueduct, and other underground sources, to irrigate vegetation in town squares and along sidewalks, which could help reduce temperatures and thus water consumption.

Awareness campaigns are important tools to change habits, experts and officials agree.

Campaigns run by the water board and local authorities in Halandri are so far resonating with residents. Sotiriou is one—she helps run an organization formed to manage the aqueduct’s water, and students have learned about water conservation while designing water tanks for their schools.

In 2023, the project won an award for urban planning and design and is now serving as a model for other cities facing water shortages. Christos Giovanopoulos, a project manager at the Halandri authority, and his colleagues are advising five cities on similar projects, including Rome, which is restoring a historic orangery (a type of greenhouse), and Serpa, Portugal, which is repurposing a 17th-century aqueduct.

Officials say they are confident of the project’s technical success— the challenge will be convincing more mayors, schools, and residents to opt into the program.

Sotiriou is doing her part at the grass roots, helping manage usage in her suburb and encouraging neighbors to get involved.

“We want people to think about natural resources and what will be left for the next generation,” she said. “We can’t leave parched earth.”