Mangroves' crucial role in protecting Hong Kong's coasts

Mangroves play a vital role in Hong Kong’s marine ecosystem, but expanded conservation efforts are needed to preserve this natural wonder.

Hong Kong has no shortage of natural treasures—from a highly diverse array of endemic flora and fauna, to globally unique volcanic rock formations—but one of its most important is arguably also one of its least appreciated: mangroves.

Found in around 60 locations spread across six areas of Hong Kong—including Sai Kung, Tolo Harbour, Deep Bay, the Northeast New Territories, Lantau Island and Tai Tam in the south of Hong Kong Island—mangrove forests are home to an abundance of marine life such as fish, shrimp and crabs, and play a crucial role within the territory’s coastal ecosystem. They are also adept at absorbing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, as well as protecting our coastal areas from storm surges and swells.

And yet, despite the many benefits they bring, these natural defenders need protection of their own if Hong Kong is to continue to enjoy the many benefits they offer.

One of the territory’s foremost authorities on mangroves is Dr Stefano Cannicci of The Swire Institute of Marine Science and School of Biological Sciences at Hong Kong University. As Principal Investigator at HKU’s Integrated Mangrove Ecology Lab, Dr Cannicci’s research focuses on the role of mangroves within Hong Kong’s coastal ecosystems, and he is quick to highlight their importance.

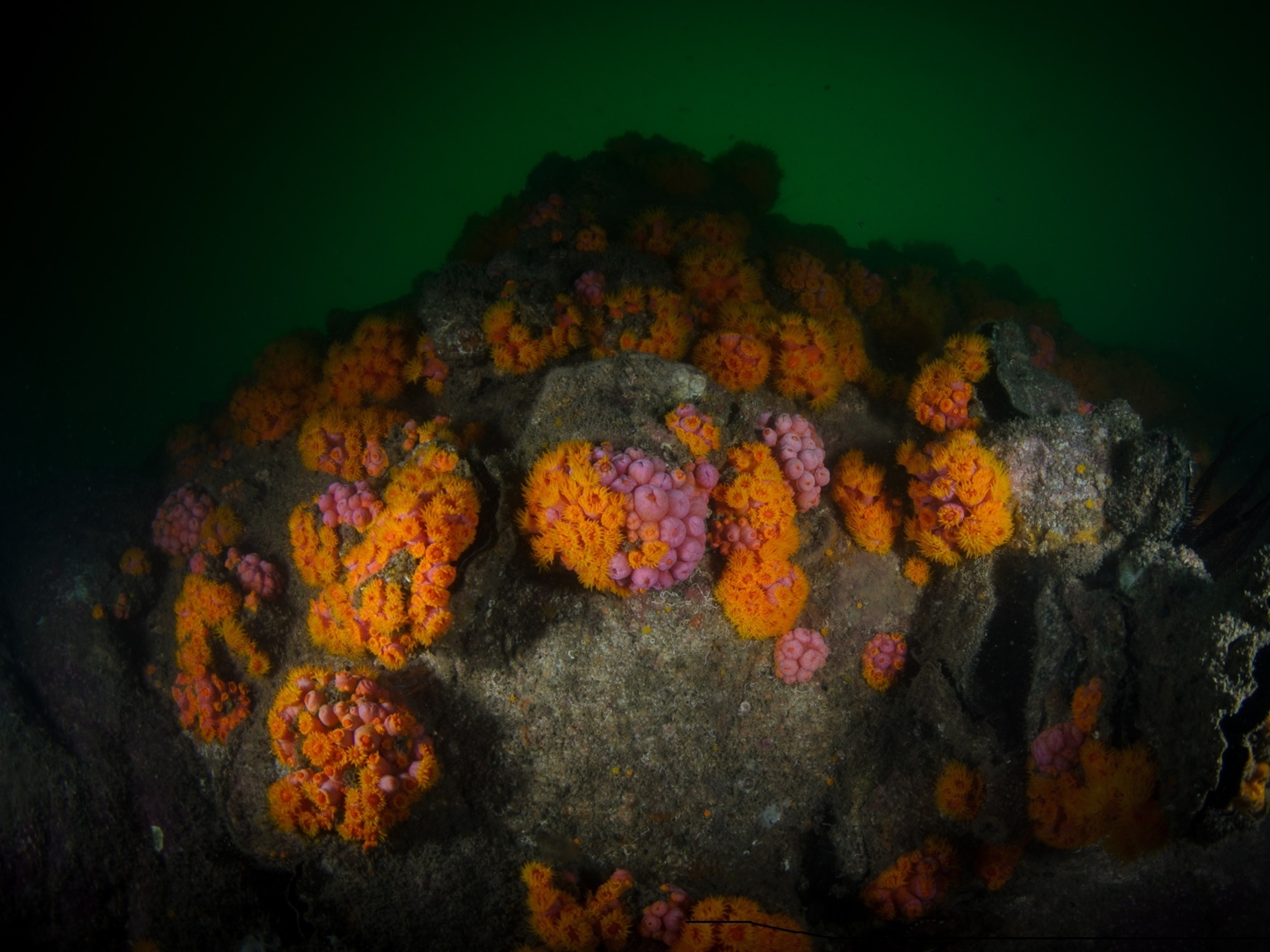

“We have to think about coastal ecosystems such as corals, seagrass beds and mangroves as a single, connected habitat,” he says. “With this in mind, we can understand how corals or seagrass beds will not thrive without mangroves, and vice versa.” Dr Cannicci also points out that mangroves provide nursery sites for juvenile fish, including for commercially important species, as well as being home to more than 50 species of crabs, including a new species of mangrove-climbing micro-crab discovered by Dr Cannicci and his team in 2017.

A natural defender

Beyond their place within the marine ecosystem, Dr Cannicci also emphasizes the significance of mangroves for humans. “Healthy mangroves are very effective in protecting coastal settlements, thanks to their root systems and the complexity of the forest,” he says. A recent example of this is when the mangroves of Mai Po Nature Reserve almost certainly saved the residential estate of Fairview Park in Yuen Long from being flooded when Typhoon Mangkhut hit Hong Kong in 2018. “Another key issue is climate change mitigation,” he continues. “No other ecosystem can replace mangroves in terms of carbon sequestration.”

Dr Dan Friess, Associate Professor at the Department of Geography and head of the Mangrove Lab at the National University of Singapore, further underlines the vital role that mangroves play in protecting coastal areas. “Mangrove roots cause friction with incoming waves, reducing their height and energy. An added bonus is that their roots can trap sediments, helping build up their surfaces and keep pace with sea-level rise.”

But while mangroves are proficient at countering forces such as these, there are other, man-made, threats that pose a much greater danger to their health and even existence.

“Nitrogen and heavy metal pollution, as well as microplastics, are a real danger,” says Dr Cannicci. “We found that the mangroves colonizing the west coast of Hong Kong suffer from a high load of heavy metals. The trees seem to have evolved strong physiological adaptations to cope with such metals, but the crabs are accumulating those pollutants. This is quite worrying, since they are the main food source of water birds that overwinter in Hong Kong, especially in Mai Po.”

In addition, large areas of mangrove forest have been cleared to make way for coastal developments and infrastructure over the past few decades, and Dr Cannicci explains that this poses another threat to their ecosystems. “Hong Kong’s mangroves are already too fragmented. On the west coast, there are remnant patches of what used to be a long stretch of mangroves. We know that small mangrove forests can act as biodiversity reservoirs, but if we keep reducing their area, will they still be functional?”

And, with increased development inevitable in the Pearl River Delta as the Greater Bay Area initiative gathers steam, pollution is likely to pose a growing problem for these forests. “We need this development to be sustainable and as green as possible to avoid intoxicating mangroves and other marine habitats. Without mangroves, the quality of the waters surrounding Hong Kong will drop, threatening all the commercial activities that depend on such waters.”

Indeed, commercial imperatives such as these may play a significant role in protecting mangrove forests in the future. Dr Friess says that there is a growing interest in incorporating mangroves into hybrid engineering, while Dr Cannicci points out that an increasing number of hedge funds and banks around the world are poised to invest in mangrove conservation to mitigate the effects of global warming.

Maintaining our mangroves

But what can Hong Kong do to help preserve its eight mangrove species? A good start, says Dr Cannicci, would be to reduce the use of plastics, especially single-use plastics, as these can harm young trees and enter the food chain of the creatures that inhabit mangrove forests. He points to the widespread use of Styrofoam in the fishing and aquaculture industries as a particular problem, making any initiatives or legislation around that particularly welcome. Dr Cannicci also highlights that mangroves are not specifically protected by law in the Hong Kong SAR, which presents another possible way to consolidate conservation efforts at a policy level.

Dr Cannicci urges for the establishment of better practices to minimize possible negative impacts on mangrove forests. “We have to be cautious in developing our coastline,” he says. “Development plans designed for particular areas and bays can have enormous effects on currents and sediment dynamics in adjacent bays.”

Moreover, education is key. “We need to change the idea that mangroves are wastelands,” says Dr Cannicci. “Too many times I have found incredible amounts of rubbish—including fridges, motorbikes and water heaters—in mangroves near rural villages in Hong Kong. We need to educate people about the importance of healthy mangroves for them, and for the environment surrounding them.”

Lastly, both experts agree that experiencing mangroves firsthand is one of the best ways to engage people in protecting them, and so they urge Hongkongers to visit and appreciate local mangrove forests, such as the SAR’s largest in Mai Po Nature Reserve.

As Dr Friess concludes, “We all rely on mangroves without even knowing it. They are working quietly in the background, soaking up our carbon emissions, supporting our fisheries, and more. But they can only provide these benefits if we protect them.”

Find out how to preserve Hong Kong’s marine biodiversity at Oceans Tomorrow.