The fight to preserve Mexico’s portals to the underworld

Can the Yucatan Peninsula’s enchanting cenotes be saved?

On a sweltering day in April 2025, a small group of cave researchers led by José “Pepe” Urbina, a veteran cave diver, and Roberto Rojo, a biologist and speleologist, trudged single file through the dense, tropical forest of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. They were about 15 miles inland from the Caribbean coast. Moving slowly, they parted the brush with a machete as they searched for signs of their destination: a remote stretch of the flooded Zumpango Cave that probably no one had set foot in for years.

Suddenly, the vegetation thinned, revealing the jagged entrance of a gaping limestone tunnel heading underground. The air chilled as the team descended, navigating carefully around large stalactites. Then someone shouted “Uy!” and everyone saw it: There was an ancient Maya pot sitting on a recessed shelf of rock.

Such discoveries are not uncommon in the Yucatan, which contains a vast subterranean network of limestone caves with rivers running through them. When part of a chamber collapses, it forms a natural sinkhole that is called a cenote, a term that originates from the Maya word ts’onot.

For the Maya people, these cenotes are sacred places where gods and spirits dwell. They are also geological wonders that may contain historic artifacts and endangered aquatic species, although some have been converted into tourist spots for visitors who want to swim in their traditionally crystalline waters.

Critically, Southern Mexico’s cenotes serve another time-honored purpose: They’re part of a deep aquifer that spans 64,000 miles and supplies the only source of freshwater to millions of people within the region. “Everyone is connected through the cenotes,” says Urbina. For him, Rojo, and a growing band of conservationists, that makes surveying exactly what’s happening inside these enchanting portals ever-more important.

Cenotes have been threatened by agricultural farming runoff and residential sewage leaks for decades. But in recent years, the arrival of Tren Maya, a rail line connecting tourist destinations across Mexico, has increased the urgency to better understand these fragile ecosystems. The 966-mile cross-country loop, which cost an estimated $30 billion to build and began running in late 2024, was constructed in part by drilling massive support pillars directly into the same bedrock that holds the cenotes.

(Cancun’s Tren Maya is a tourist’s dream—and an underground nightmare.)

At the same time, Urbina and Rojo fear that increasing development in the train’s shadow may impact cenotes even more. For years, the duo worked separately to sound the alarm about these treasured spaces. Urbina runs a conservation group called Sélvame del Tren, and Rojo cofounded Cenotes Urbanos. But it wasn’t until Tren Maya was announced that they joined forces and a larger movement coalesced.

Now that rail line is fully operational, they’re part of collective of at least 10 different cause groups that are racing to catalogue the ecosystem’s many changes before it’s too late. “I trust wholly that there are solutions,” says Rojo, although he worries it may take generations to undo the ecological damage.

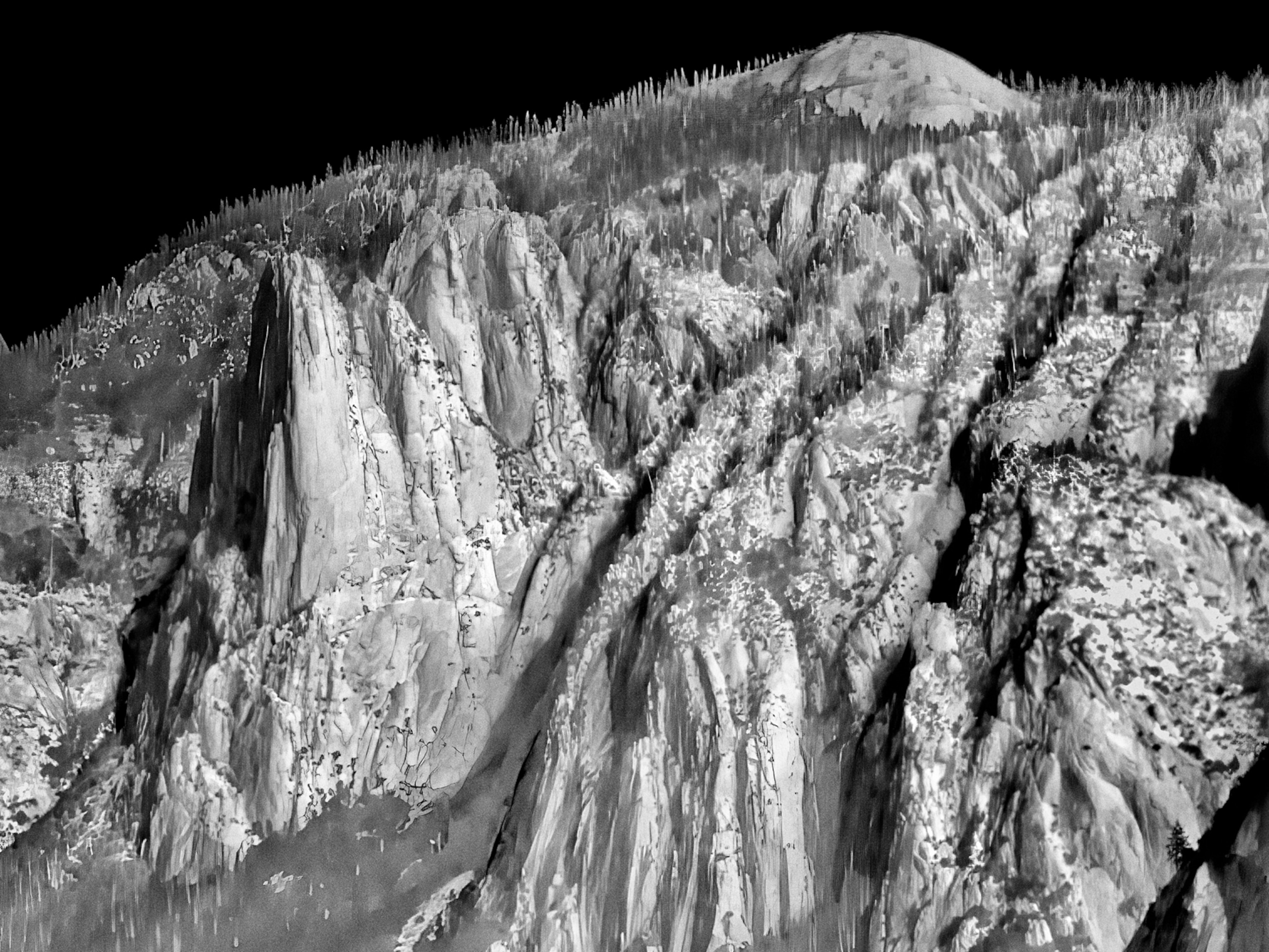

One major challenge is understanding the scope of the network. There at least 8,000 registered cenotes in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, but because sinkholes can appear suddenly, as limestone cedes to centuries worth of fissures, there could be many more. To chart the underground system, Urbina and other divers have mapped roughly 900 miles of caverns. Still, he estimates that is only about 10 percent of the overall maze.

One thing is clear: Pollution can easily travel through water flowing from one cenote to another and, eventually, out into the sea. Flor Arcega-Cabrera, an environmental geochemist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, says the agricultural industry has become the single largest source of contamination. Her research shows that animal waste laced with hormones, fertilizers with heavy metals, and pesticides from crop fields are likely trickling into the aquifer. This matters because people use well water and feed it to their babies, Arcega-Cabrera says. For example, nitrate, a common ingredient in fertilizer, can replace iron in the blood. This may result in blue baby syndrome, where babies’ systems are no longer able to carry oxygen through their body.

Many residents without access to sewage treatment facilities also filter sewage through the soil—a system that causes issues with porous limestone. (Once, as Rojo was exploring a cave, he heard the faint whoosh of a toilet overhead and watched as excrement rained down around him.) Near tourist sites and industrial parks, some cenotes have also been turned into illegal dumping grounds.

And then there’s the train. Construction on Tren Maya began in 2020, even as many scientists, cave divers, and members of local Indigenous communities objected. Urbina, who has been a cave diver for more than thirty years, joined a lawsuit that reached Mexico’s supreme court and briefly suspended construction in 2023. But the win was short-lived. Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador, citing issues of national security, simply called in the military to finish the job.

In total, Tren Maya is now anchored by 15,000 pillars, some of which were driven into cenotes. Researchers worry about what archeological discoveries might have been lost along the way. In 2014, a diver stumbled upon the 13,000-year-old skeleton of a girl within a cenote. Scientists later established she was genetically related to modern Native Americans—a revelation that has led to a more accurate understanding of how the Americas were first populated.

The caverns also serve as a critical habitat for animals like jaguars, tapirs, opossums, foxes, and coati, which use cenotes as a water source. “When you arrive at a healthy cave, you see crickets, blind fish, blind shrimp, bats,” Rojo says. But when a cave is impacted, the original inhabitants are overrun by cockroaches and rats.

Today, Sélvame del Tren and Cenotes Urbanos stay in regular contact to maximize their research and find ways to inspire more public awareness. The expedition to Zumpango Cave, for instance, was part of a combined effort to map and track the health of existing caves within the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, which includes resort areas like Cancún and Playa Del Carmen that are now easily reachable by train.

While Urbina started Sélvame del Tren to raise awareness of environmental concerns on social media, organize peaceful protests, and monitor pollution, the scope of the organization has expanded to tracking how the train has interrupted animal movement in the region. Since Rojo founded Cenotes Urbanos alongside fellow activists Talismán Cruz and Ximena Chávez nearly eight years ago, the group has grown to almost 500 members. They now conduct about twenty annual re-dignifying expeditions to pick up trash and collect water samples and host workshops on mapping and spelunking.

Guillermo D. Christy has worked as a water quality consultant for over 25 years, advising hotels on purification and treatment processes. Now he’s partnering with Sélvame del Tren and Cenotes Urbanos to measure water quality in eight caves in Quintana Roo that are home to increasingly threatened animals that have specially adapted to live in the darkened caves, such as the blind swamp eel (Ophisternon infernalis) and the Mexican blind brotula (Typhliasina pearsei), a transparent white fish. He tests for things like increased salinity, heavy metals, and bacteria like E. Coli. So far, the effort has revealed elevated levels of E. Coli in the region, which D. Christy has shared with local communities and government officials to encourage better sanitation practices.

D. Christy has also been analyzing water samples from cenotes penetrated by Tren Maya’s support pillars. The tests show iron oxide in the water, a sign that metal from the piles may be leaching out. Large concentrations of these chemical compounds can spur blooms of toxic algae, says Arcega-Cabrera, which could affect the development of eggs and larvae from animal species that live in the cave.

Earlier this year, Urbina, Rojo and D. Christy took officials from Mexico's Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) and the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP) to Oppenheimer Cave, another cenote about thirteen miles outside Playa del Carmen. As they passed from the first chamber into the second, turquoise waters and towering stalactites gave way to muck and concrete pillars that oozed iron oxide.

In the weeks after their visit, officials from SEMARNAT made a public announcement concluding that the construction of Tren Maya had damaged ecosystems in Yucatan. More than seven million trees were felled, and 125 caves and cenotes were punctured as pillars were installed. The agency has committed to a rescue plan, which involves removing fences that are impeding wildlife movement and prohibiting the construction of secondary roads to touristic sites.

For his part, Urbina believes that if government officials see the beauty of these places, they will want to protect them. One day this April, he took Oscar Rébora Aguilera, the Secretary of Ecology and Environment in Quintana Roo, cave diving in Sac Actún, one of the largest flooded cave systems in the world. As they emerged from the water, he says he told Aguilera about plans to put a road overhead. Soon after, the Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection issued a temporary order to suspend the construction. It’s one sign that their collective efforts may be paying off.