The ‘timber detectives’ on the front lines of illegal wood trade

Germany’s Center of Competence on the Origin of Timber tracks down which EU wood imports come from illegal sources in the world’s third-biggest criminal sector.

Hamburg, Germany — Under tungsten light on a bleak winter day, Gerald Koch gazes up from a black microscope, adjusts his rimless glasses, and gestures at a monitor displaying a slice, thinner than a hair, of suspected illegal timber.

“I only need to look at these two to know immediately it comes from South America,” he says, pointing at a pair of large white cells on a canvas of charcoal gray. “This is down to our years of experience.”

The quiet corridors of the Thünen Institute, a cluster of dreary, 1960s-era concrete buildings in a leafy suburb of Hamburg in northern Germany, might not tally with the image of a world-leading hub fighting international crime. But housed in a second-floor laboratory overlooking the institute’s 22-acre grounds, which are filled with 1,500 tree species, is the foremost center for timber authentication in the world.

“A lot of the timber being illegally logged is difficult to trace and often customs declarations are wrong,” says Koch, who leads the institute’s Center of Competence on the Origin of Timber. “It’s our job to uncover the truth.”

The illegal timber industry, worth $152 billion a year, is the world’s third largest criminal sector after drugs and counterfeit goods, according to Interpol. As the global wood trade has boomed—the value of forest product exports more than quadrupled between 1980 and 2020—so too has the awareness of its illegal component. The WWF estimates that 16 to 19 percent of the European Union’s wood imports come from illegal sources.

Funded by the German government, the Hamburg institute acts as a scientific authority for government agencies, timber traders, and consumers on the origin of wood products.

Every day a team of 15, including four forensic scientists, inspects a curious array of wooden objects—from children’s toys to window frames, coat hangers, and umbrella handles—to determine where they were made and whether they were made of endangered or protected trees. The team alerts German authorities if any sample is found to be in breach of the European Timber Regulation, which since 2013 has banned illegal timber imports, or the Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), a multilateral treaty to protect plants and wildlife.

Koch’s team are, as a tongue-in-cheek sign on their laboratory door puts it, “the timber detectives.”

A musty archive of wood

With 41,000 samples from 11,300 different tree species, the Thünen Institute’s wood library, called a xylotheque, is one of the world’s largest collections of authenticated wood specimens. Its size allows the team to determine the genus of practically every traded wood—legal or illegal—by comparing the fresh samples with the extensive archive.

In one musty room, thousands of specimens in every imaginable shade of brown line the shelves. Another holds such rarities as a 300-year-old Siberian larch trunk, a Mexican bowling ball made of guaiacum—one of the densest and hardest known woods, as heavy as coal—and a tool used to fix pyramid stones in place during the rule of Tutmoses III, around 1400 B.C.

In 2021, the Thünen Institute produced around 1,000 in-depth reports on timber and 10,000 analyses of individual samples. “We have never failed to identify a sample,” says Koch. As many as 25 percent turn out to have been wrongfully declared.

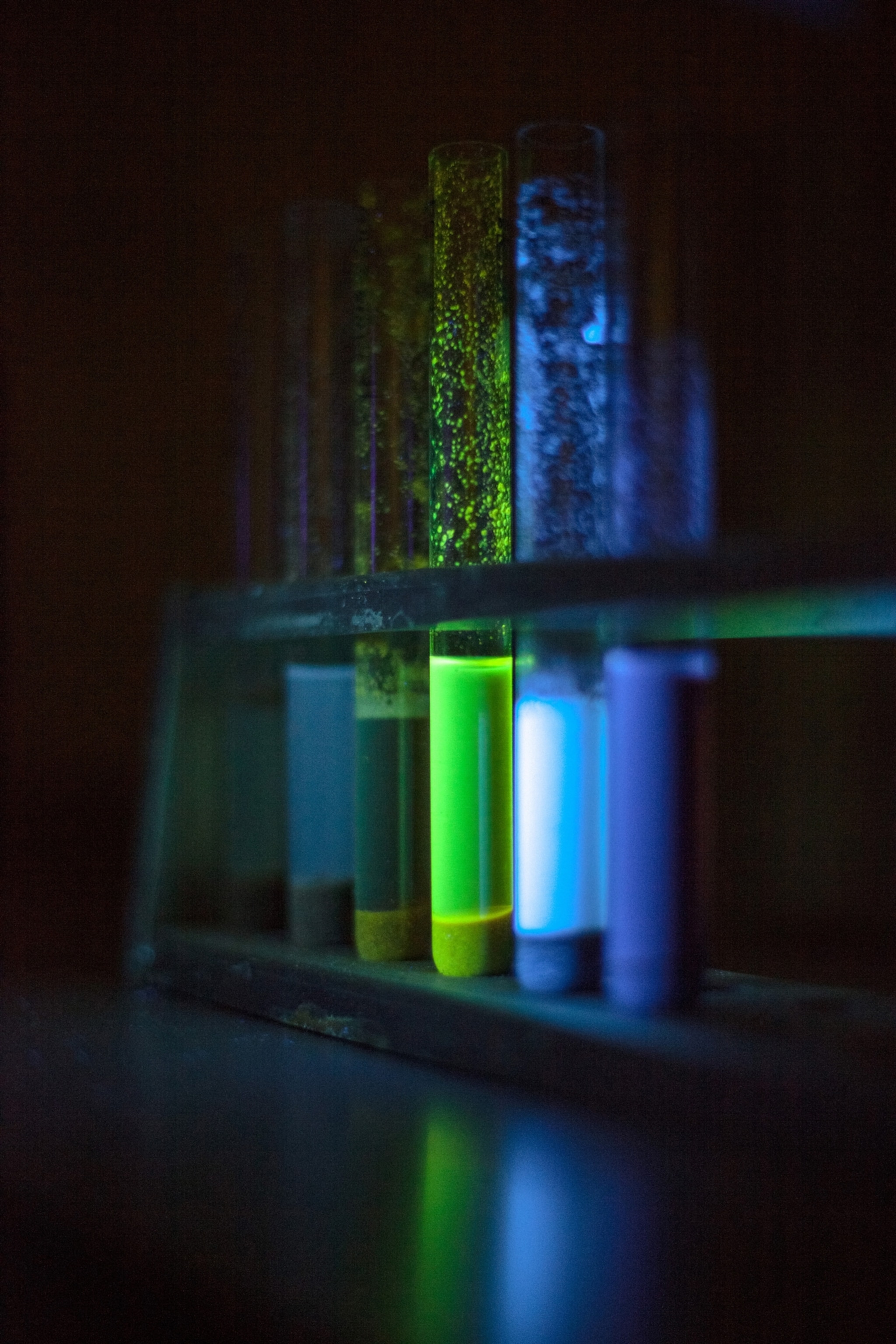

As part of the identification process, cubes of wood are cut from each sample, boiled in water for 30 minutes to remove air bubbles, and then planed into microscopic slices. The specimens are then analyzed under a microscope and compared with the tens of thousands of samples in a digital database.

Requests come from far and wide, but more than three-quarters are by European companies doing due diligence to ensure their products’ materials are legal.

“‘Are these decking boards made of durable Bangkirai or lesser-quality wood substitutes?’” says Koch. “‘Has the origin of these mahogany logs been properly declared?’ ‘Are the importation documents correct and genuine?’ These are just some of the questions we must answer.”

Faith Doherty, forests campaign leader at the Environmental Investigation Agency, an international nonprofit that gathers field evidence of illegal logging, says that

paperwork alone can no longer be trusted. “What’s become abundantly clear is that signing a document isn’t enough for verifiability,” she says. “We need to go on the ground to see what’s really happening and analyze products being manufactured.”

Since 2013, when the Center of Competence on the Origin of Timber opened, orders for anatomical wood analyses have more than tripled. But the proportion of wrongful declarations has fallen—which is taken as a sign of improvement.

John Hermanson, a research scientist at the University of Washington’s School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, believes the institute’s work is more important than ever before. “They’re playing a big role in what is a huge global issue,” he says. “They’re engaged in the global community, as well as bridging that gap between science and practice, bringing these cases to light for authorities.”

For the U.S. Forest Service, Hermanson is developing a handheld device called the XyloTron, which scans and quickly identifies timber using the service’s own collection. “Getting high-quality samples is difficult,” he says. “It’s expensive. That’s where having a xylarium like they do in Germany is very useful.”

Blind spots remain

There are limits to what the timber detectives can do. While they can determine the genus of a sample, ascertaining exact species or geographical origin can be more difficult. The same tree species can grow in more than one country or even continent; timber can be harvested, processed, and manufactured into products across multiple regions before being sold. Paper products, whose fibers are macerated and therefore harder to analyze, can be even more of a problem.

“One notebook could be made of wood from eight countries in three continents—the hard cover, front pages, and inner pages could all be different,” says Hermanson.

But the Thünen Institute, which researches sustainable uses of natural resources across agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, is multidisciplinary, so Koch’s team of wood anatomists can draw on the expertise of specialists in forest genetics, trade, and economics from other departments. Forgery experts can sniff out fake customs paperwork; geneticists can find clues to a piece of wood’s geographical origin.

Blind spots remain, however—for example, genetics can’t verify whether timber was grown wild or on a plantation, which can be crucial for determining illegality. The institute is developing the use of stable isotope analysis, a process that measures the proportions in a sample of heavier or lighter versions of particular chemical elements such as nitrogen, to help pinpoint the geographic origin of wood.

“Wood anatomy, which has been in use for a century, must be deployed with other techniques,” says Peter Gasson, lead wood anatomist at Kew Royal Botanical Gardens, London. “Two or three techniques in combination will give you a much more refined answer.” He’s involved in the WorldForest ID program, a new project run by a consortium of organizations to improve wood authentication.

Meanwhile, emerging technology could vastly improve the speed and capacity of the Thünen Institute’s work. During a three-year collaboration with the Fraunhofer Institute, a research organization, microscope specimens are being used to train artificial intelligence software to identify timber. “It could do in one night what would normally take our team a month,” says Andrea Olbrich, the project lead.

But for now, as the rapid logging of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Siberia continues, the old-school sleuthing of Gerald Koch and his fellow detectives remains the primary way to identify illicit timber. And their huge archive needs to grow. A study published in January estimated that there are about 73,000 tree species, 14 percent higher than the current known figure.

“We’re a long way away from having a comprehensive collection,” says Koch. “We must continue to build on that and improve our knowledge. Even though our methods are improving each day, so are the criminals that we are fighting against.”