Unique trees from Nat Geo’s photo archives mark amazing moments

From sequoias to cherry blossoms, the National Geographic archives record a long love affair with trees.

Every tree tells a story. It may be a memorial to sorrow, an expression of belief, or a signpost of history. Most of all, these narratives speak to how trees nourish the earth and us. It is no stretch to say that trees exhale so that we might inhale, but they enrich us in other, more spiritual, ways. Buddha, after all, found enlightenment under a Bodhi tree in Nepal, an event echoed by John Muir’s observation that “The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.”

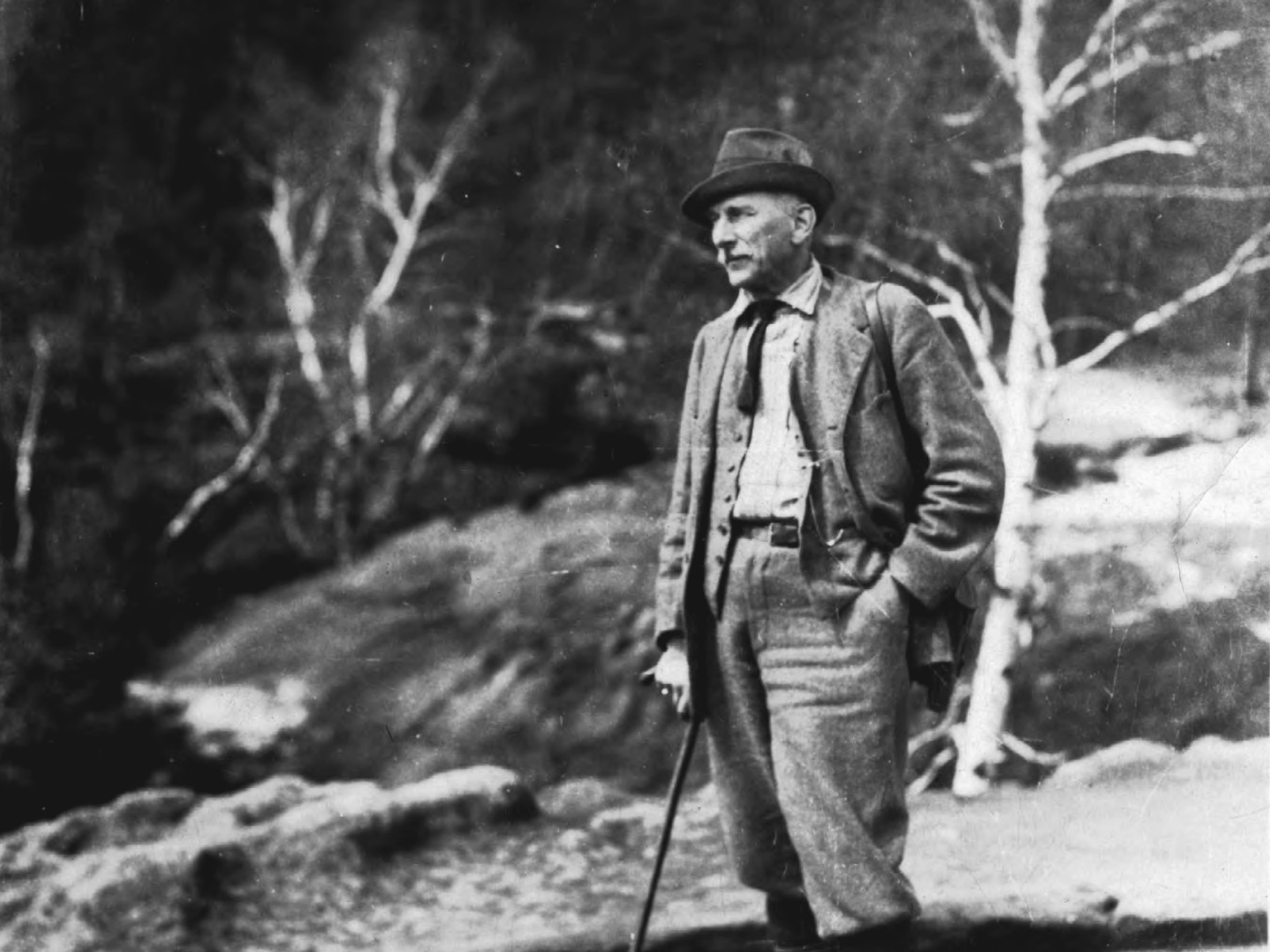

As our photographic archives reveal, for more than a century, National Geographic has used the power of the image to champion and spotlight trees, especially irreplaceable giants like the redwoods and sequoias that form the centerpiece of national and state parks in the western United States. In 1921, the National Geographic Society donated $100,000 to save what would become the Giant Forest of California’s Sequoia National Park, then imperiled by logging. The effort was spearheaded by the magazine’s first full-time editor, Gilbert H. Grosvenor. In his office he kept a photograph he took of 20 men linking their arms around the mammoth trunk of the 2,200-year-old sequoia known as General Sherman. “It’s like they were protecting it,” he said.

Grosvenor’s son and successor as editor, Melville Bell Grosvenor, would do the same for redwoods. He dispatched the Society’s senior scientist to a California forest to find the “world’s tallest tree”—a 367-foot-tall redwood. Grosvenor had the stupendous tree’s portrait made with a tiny figure (which just happened to be himself) standing beneath it. The image appeared on the cover of the July 1964 issue, and the Society donated $64,000 toward a study that helped establish Redwoods National Park in 1968.

The magazine would faithfully return to these trees, most notably in December 2009, when it published the image of a 300-foot-tall redwood in a California state park. Photographer Michael “Nick” Nichols and his crew rigged a nearby tree and incrementally lowered three remote-controlled cameras to shoot 84 top-to-bottom images of the mammoth redwood; the photos were then digitally stitched together. The six-page foldout that resulted, Ken Geiger, the picture editor on the story said at the time, “was an impossible view—the photographic equivalent of reaching Mars. You couldn’t see the tree that clearly even if you rented a helicopter.”

Nichols pulled off a similar feat for the December 2012 cover, which featured a 247-foot-high sequoia crowned with snow in Sequoia National Park.

Other less lofty, but no less memorable, trees have starred in the magazine pages or reside in its image archives. Some of the photos’ stories are poignant, such as the catalpa trees outside a Civil War hospital in Virginia, where Walt Whitman witnessed amputated arms and legs tossed out of a window, or the Callery pear “survivor tree” left standing after the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center.

Some are inspirational: the apple tree in a grove at Sir Isaac Newton’s childhood home in Woolsthorpe, England, that reportedly inspired his eureka moment about the laws of gravity, and the whimsical tree with serpentine branches at Christ Church College, Oxford, that was the inspiration for the favorite perch of the Cheshire Cat in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

And then there are the celebratory images. In 1885, Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, the Society’s first female writer, photographer, and board member, visited Japan and was enchanted by the flowering cherry trees that bordered the Tokyo’s Sumida River. After returning home, she petitioned officials in Washington, D.C., to plant trees like them. First Lady Helen Taft used her clout to get the idea off the ground—or, rather, firmly planted in it. The first of the trees (among 3,000 donated by the Japanese government) were placed around the Tidal Basin on March 27, 1912, and are today the spring glory of the annual National Cherry Blossom Festival.

Yet, the shadow of ephemerality persists. Nothing, not even a millennial-old tree, is guaranteed forever status. In 1990, photographer Sam Abell photographed a boab tree that, in the austere landscape of Western Australia, had turned white with age. When the magazine published the photo, Abell’s guide returned to the spot to re-photograph it with the page bearing the image held up in the foreground. By then only a skeletal trunk remained. After more than 900 years, the boab had been struck by lightning.