The disease detectives who solve the world’s strangest outbreaks

When weird fungal epidemics crop up in far-flung places, scientists work together to unravel how the microscopic murderers show up and turn deadly.

In 1999, hikers on Vancouver Island suddenly began falling mysteriously ill. Doctors found strange nodules growing on their lungs, and several people died as cases mounted over the next few years. The culprit was Crypotoccus gattii, a microscopic fungus that typically lives on rotting logs in tropical rainforests and that had somehow found its way thousands of miles north.

“We had this new fungus showing up in the Pacific Northwest that wasn't supposed to be there,” recalls molecular epidemiologist David Engelthaler, who was called in by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to investigate the outbreak. The immediate question: “How on earth did it get there?”

Engelthaler and his fellow investigator, microbiologist and immunologist Arturo Casadevall, delved into genetics, shipping records, and soil samples. And the answer they found astounded them. As it turns out, the same strain of C. gattii had been present in Brazil over a century earlier. From there, it likely hitched a ride north in the ballast water of cargo ships after the Panama Canal opened in 1914. The ships dumped their water around Vancouver Island, where the fungus lived harmlessly off the coast for decades. Then, the Great Alaska Earthquake struck in 1964, triggering tsunamis along the Pacific Northwest coast—moving C. gattii onto land and allowing it to colonize the entire coastline at the same time, as soil samples suggested. It took 30 years for the fungus to fully adapt to life on land and grow ever more virulent. Then, it started killing.

The Vancouver Island cases might sound like a freak accident. But with climate change and the resulting uptick in frequent and severe natural disasters, fungal diseases are increasingly showing up in unusual places—in the wake of a tornado in the Midwest, the floodwaters of a hurricane or around archaeological sites. Meanwhile, scientists like Engelthaler and Casadevall are in a critical race to stay one step ahead of the microbes, as they piece together the weird, surprising paths fungi take to infect people. Casadevall and his colleague Daniel Smith have coined a term for their work: disaster microbiology. With each new case solved, they can help predict future outbreaks—and, potentially, save lives.

(Can an early-warning system for viruses help stop pandemics before they start?)

How investigators trace dangerous fungi

The CDC estimates that fungal ailments—from ringworm and minor yeast infections to more serious respiratory diseases such as aspergillosis and histoplasmosis—cause 13 million outpatient visits, 130,000 hospitalizations, and over seven thousand deaths in the U.S. annually, costing the economy $19.4 billion. And the true burden is likely higher as many fungal diseases go unreported. Worldwide, fungi kill 1.5 million people each year, especially as multidrug-resistant strains emerge, and cases are trending upwards.

Human immune systems and high body temperatures typically kill most fungi (unless the immune system is compromised). But as these organisms adapt to a warming climate, that may soon change. In other words, humans don’t yet have to worry about getting zombified by fungi as in the fictional apocalyptic world of The Last Of Us, but fungi are becoming an increasingly real threat.

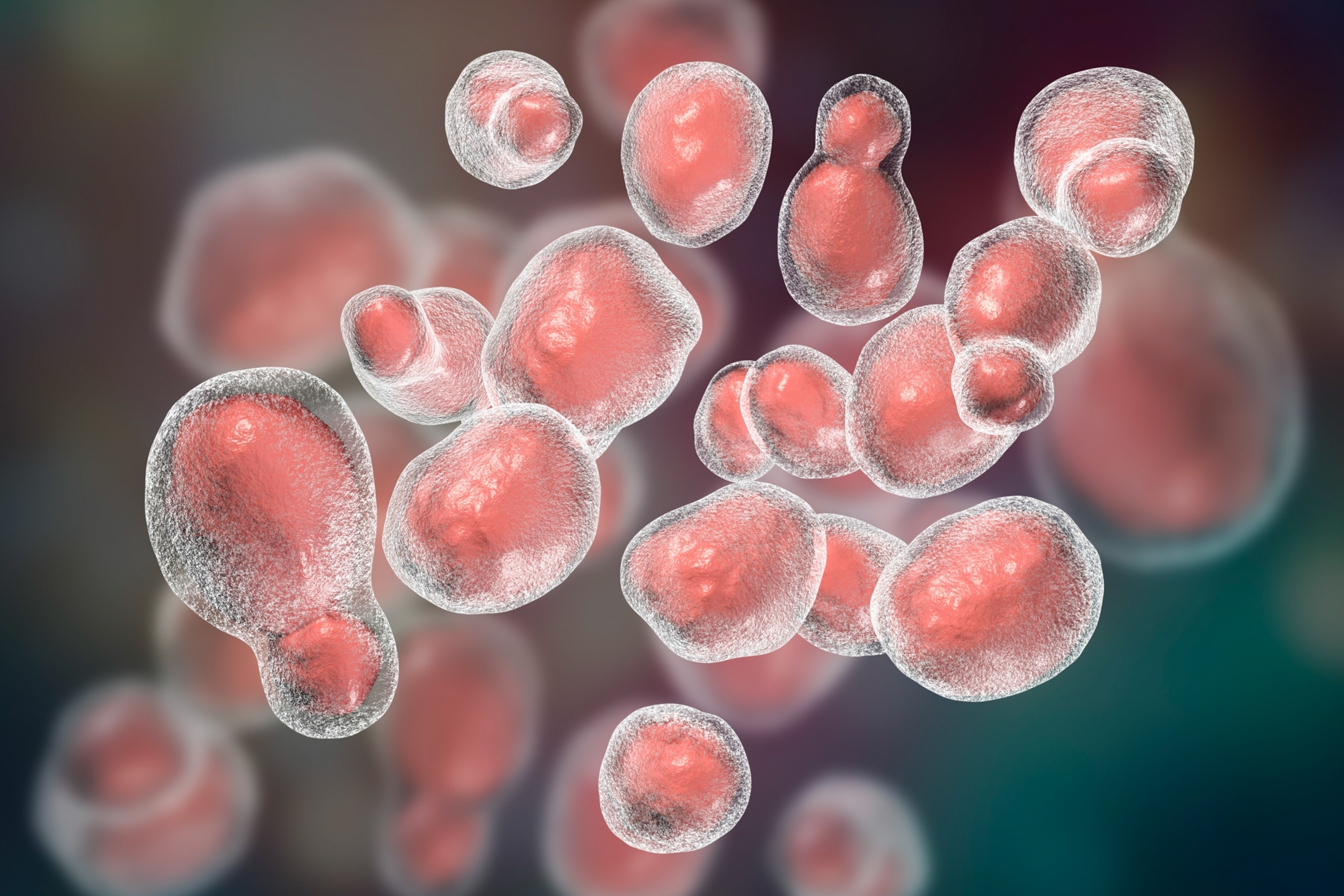

In 2019, Casadevall, now a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins University, found that a newly discovered species called Candida auris had emerged on three continents simultaneously as a deadly drug-resistant human pathogen, the first to “break through” thanks to climate change and adapt to higher environmental (and thus, mammalian) body temperatures.

At the same time, climate change is fueling more frequent and severe natural disasters that can physically reshuffle the environment, leading to fungal outbreaks in unlikely places. The CDC has typically deployed the first responders to deal with such outbreaks—officers from the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS). “They're used to being helicoptered into a hot zone and making sense of the chaos and the crisis,” says Seema Yasmin, an alumna of the program now at Stanford University.

Take, for example, the 2011 tornado that hit Joplin, Missouri. In the aftermath, patients showed up to local hospitals with deep cuts infected with a fungus called Apophysomyces variabilis. The fungus thrived in patients’ vascular systems, clogging arteries and spreading quickly.

To figure out how the fungus had infected its victims, EIS officers and scientists sampled soil along the tornado’s path and compared the fungi found there genetically with those extracted from patients’ wounds. In this case, they determined that A. variabilis had likely lived quietly in the Missouri soil for millions of years without ever causing a human outbreak. Then, the tornado spun it into the air along with water from ponds and bits of sharp debris that introduced the fungus to human bodies through penetration wounds.

Fungi similarly spawned outbreaks after a Columbian volcano erupted in 1985 and following Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

Critically, to determine an outbreak’s origins, investigators need to understand the entire environmental system, says Engelthaler, now executive director of the Arizona State University Health Observatory, and who was also involved in the Joplin tornado investigation. “We're missing most of the picture, almost all the picture, if all we're doing is looking at human cases.”

These infections following tsunamis, earthquakes, tornadoes and more showed fungal outbreaks can be difficult to predict, as disasters reshuffle human and microbial communities alike in unexpected ways and to devastating effect. But the lessons from Joplin and similar events have shaped how first responders and physicians approach natural disasters—to expect and be ready for the unexpected.

A threat from the deep past

Even when a natural disaster isn’t involved, solving a case often requires the collective brainpower of many different experts. When a valley fever outbreak struck Washington State in 2010, Engelthaler teamed up with soil and fungal biologists, experts on aerosolization, and anthropologists and paleoclimatologists to dig deeper into what was fueling the spread.

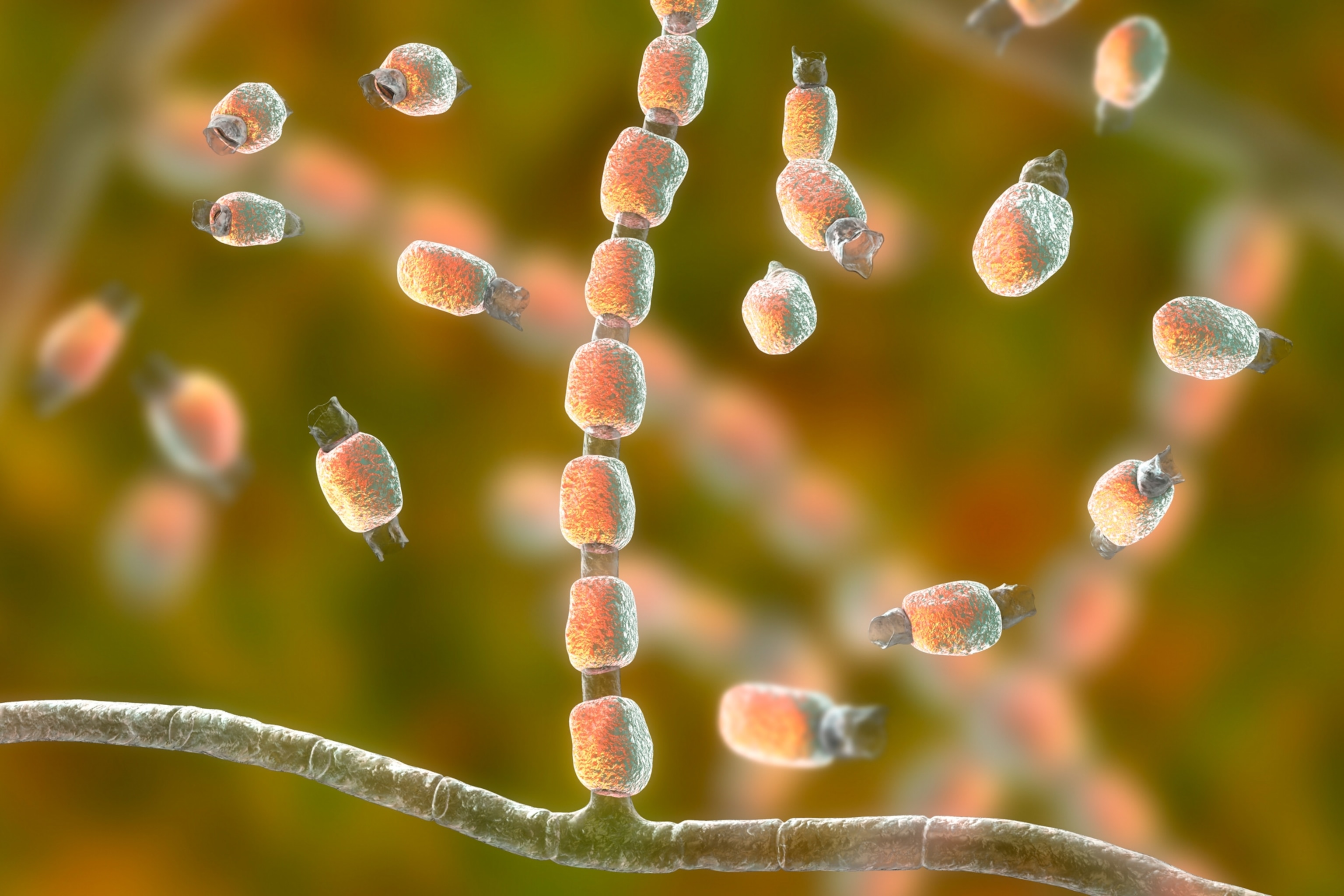

Washington is well outside the known range of the fungus that causes valley fever, Coccidioides immitis, which thrives in the hot, dry soils of the Southwest. At first, the researchers thought that dust storms following long droughts could be transporting fungal spores to new places. Indeed, valley fever has become a poster child for expanding disease ranges in a warming world.

Yet evidence began to stack up that the picture might be more complicated, at least in this instance. Soil studies did show that the warming climate had dried out the environment enough in central Washington for the fungus to survive. But genetic evidence suggested that the fungus was likely introduced only once, perhaps as many as 10,000 years ago. Back then, the area was even more arid and warm than it is today, providing a perfect incubator for C. immitis.

But how did it first get to the region? More clues emerged: The fungus thrives in animal carcasses, especially dogs. It severely infects the soil within 10 meters of a dead animal in lab studies and has turned up at archaeological sites with both human and canine remains. In one case from 1970, C. immitis infected 61 archaeological students at a dig site in Chico, California. Meanwhile, a decade before the disease popped up in the area, a 9,000-year-old skeleton called the Kennewick Man was discovered close to the Washington outbreak site. Shell beads from coastal California had also been found nearby, suggesting the presence of ancient long-distance trade.

Engelthaler’s theory? Thousands of years ago, an infected human or their dog likely carried the fungus up to what is now eastern Washington and died, contaminating the soil in just one place where they were buried. Warming temperatures helped the fungus thrive, but only in the infected location, although the full geographic range is still under investigation—meaning we shouldn’t necessarily expect valley fever to spread just anywhere even though temperatures are rising.

“We have to think about really deep time,” says Engelthaler. “We have to embrace complexity and bring these different pieces into models to understand how things got to where they are, how they may be changing, and where the risks are in the future.”

When clinical cases and evidence of fungal contamination pop up in surprising places in the future, Engelthaler hopes researchers will be primed to think across disciplines, piecing together genomic, geographic, climatic and anthropological evidence to suss out the scale and cause of each outbreak.

Facing an uncertain future

Valley fever cases have quadrupled in California over the last decade—possibly driven by a combination of droughts and wildfire smoke, or so disease detectives think. Cases hit record levels again this year. Yet fighting future fungal outbreaks and developing new treatments might get even harder with shrinking funding that has impacted the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) program as well as Johns Hopkins University, home of Casadevall’s lab, which is working on developing fungal vaccines.

The EIS program onboarded 47 new officers in its 2025 class, many of whom are assigned to state and local health departments, a CDC spokesperson said in a statement to National Geographic. The two-year program normally averages between 65 to 80 new officers each year. In October amid the government shutdown, around 70 EIS officers were abruptly laid off and then reinstated, according to reporting from the New York Times.

Since fungal diseases don’t typically infect many humans at once, they don’t get a ton of attention from private drug companies. Even the more common fungal pathogens get less attention than bacterial and viral superbugs. Though valley fever sickens hundreds of thousands of Americans, mostly in the southwest U.S., each year, the CDC still considers it an “orphan disease” since it’s a regionally limited scourge.

Grimly, for those infected, that means existing treatments are limited, and no vaccines currently exist. In cases where fungi have never caused an outbreak before, treatment options can be brutal. For example, no anti-fungal drug for A. variabilis exists. After the Joplin tornado, “it was Civil War treatment,” says Engelthaler. “It was amputation. You had to get ahead of it, so the fungus didn’t go to other parts of the body.”

“Biomedical companies, they have a bottom line they have to worry about,” says Engelthaler. “So, if they’re not going to make money, in the end they can’t put resources towards it. That’s why we need science for the public good.”

And in a globalized and warming world, “a threat anywhere,” he adds, “can become a threat everywhere.”