Doctors are worried about prescribing GLP-1s to certain patients

With one in eight adults taking drugs like Ozempic and Mounjaro, emerging evidence shows that the medication has potential to both help and harm people with eating disorders.

When Chevese Turner first discussed Ozempic with her doctor to treat her diabetes, she was both worried and relieved. Finally, “there was something effective that [was] going to address my diabetes,” says Turner, the CEO of the Body Equity Alliance.

But as a weight discrimination activist, Turner knew how others in her community might view her taking a drug associated with rapid weight loss. She worried, too, about what it might mean for her eating. She is in recovery from a long, complicated relationship with food, and has experienced symptoms of both binge-eating disorder and atypical anorexia.

“After a lifetime of using food to help manage my emotions, and then using restriction to help manage my emotions, I was always using one or the other,” she says. Even if the drug caused fewer cravings, the instinct to use food or restriction to manage emotions was still there. “Those brain patterns didn’t just disappear,” Turner adds.

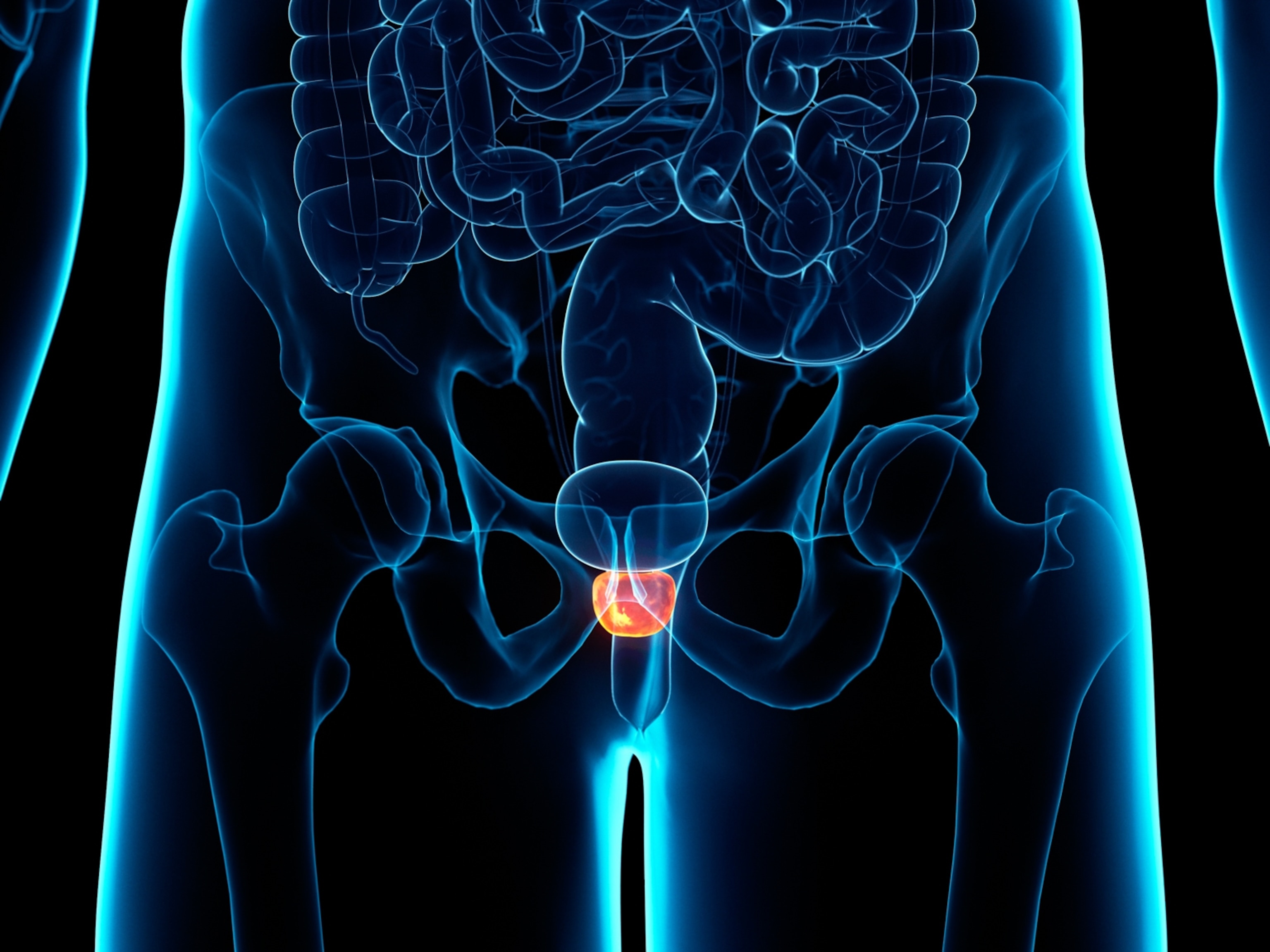

For people who have yo-yo dieted for years, or struggled to manage their diabetes, GLP-1 receptor agonists—drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy—can feel like a saving grace. These medications increase insulin production, reduce appetite, and delay gastric emptying, making people feel much fuller longer. Newer drugs like tirzepatide (sold as Zepbound and Mounjaro) combine GLP-1 drugs with glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptors to increase potency. They also appear to reduce food-related responses in the brain, quieting the constant “food noise” that can drive cravings. Sometimes, it doesn’t appeal at all.

The lack of appeal could help some people. There is early evidence that GLP-1 drugs might help reduce episodes of binge-eating, and researchers are now studying how they compare with current treatments.

But the same shift that can be helpful for some may be risky for others. Clinicians who work with people recovering from restrictive disorders like anorexia worry that the same appetite-suppressing effects could reignite harmful patterns. Screening for eating disorders before prescribing the drugs may help, but no national guidelines require physicians to do so—most professional groups only recommend it. With an estimated one in eight adults now taking a GLP-1, experts fear that vulnerable patients might start misusing the drugs to achieve weight loss at any cost.

Why anorexia may go undiagnosed

Media portrayals of disordered eating often focus on anorexia nervosa (AN), a psychiatric disorder marked by severe food restriction, intense fear of weight gain, and dangerously low body weight. But many people experience the same restrictive thoughts and behaviors while remaining in larger bodies—a condition called atypical anorexia (AAN).

“The main difference, really, is that folks with atypical anorexia are within the ‘normal’ or above weight range, according to BMI, while someone with anorexia nervosa would have BMI in the underweight range,” says Sara Bartel, a psychologist specializing in eating disorders at Nova Scotia Health in Canada. “Both individuals will be just as concerned about body size, concerned around weight gain, weight and shape really determining how they feel about themselves.”

(Why BMI fails to measure health—and what works better.)

A 2021 review suggests that between 0.2 percent and 4.9 percent of the population may meet the criteria for atypical anorexia. “It’s hard to say exactly how prevalent it is,” says Samantha DeCaro, a psychologist in Pennsylvania and the director of clinical outreach and education at the Renfrew Center, an eating disorder treatment program. “A lot of times these symptoms get lost in diet culture.” Because people in larger bodies are often praised for weight loss, she says, clinicians may miss early signs of relapse when these patients start GLP-1s.

The risk of relapse

There are no clinical studies on the effects of GLP-1s on symptoms of anorexia or atypical anorexia. “We don't have any data on these drugs and people with eating disorders,” says Susan McElroy, a psychiatrist at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Ohio, largely because obesity and eating disorders are still viewed in medicine as separate, rather than overlapping, conditions. “We feel that they overlap much more than people realize.”

But psychiatrists are beginning to see hints of what can happen. McElroy has published several case studies based on patients she’s treated. (McElroy has previously consulted for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and other companies.)

One case, published in 2025, involved a woman who had been treated for anorexia as a child and was later prescribed tirzepatide for diabetes, hypertension, and liver issues. The medication helped her metabolic conditions, but also appeared to reignite old restrictive patterns, prompting her to over-exercise and secretly continue dosing even after her physician stopped the prescription. A 2024 case described a similar pattern in a woman with childhood anorexia who misused semaglutide to lose significant amounts of weight. These cases are a small sample, McElroy says, but in both, “the tirzepatide seemed to activate the past history of anorexia,” McElroy says.

(Eating disorders are on the rise in older women—and menopause is playing a role.)

While the case reports are worrisome, McElroy says the GLP-1s themselves are not the issue. “People with anorexia misuse drugs with weight loss properties,” she says. In her practice, McElroy has seen patients misuse everything from stimulants to laxatives as part of their illness. The only difference, she says, is that the GLP-1 drugs work so very well. Because of that potency, “I won’t give you a GLP-1 if I discover that you had a period of anorexia, or even atypical anorexia,” she says.

Other researchers are documenting similar concerns. A 2023 analysis of adverse-event reports submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration found that misuse reports for semaglutide were four times higher than for other GLP-1 drugs at the time. Those misuse rates were comparable to those for phentermine-topiramate (Topamax), a combination weight-loss stimulant drug.

“These medications [GLP-1’s], they are extremely useful, extremely important. They are a breakthrough,” says Fabrizio Schifano, a psychiatrist at the University of Hertfordshire in England and co-author of the study. But “some people who are the vulnerable clients, including [those with] eating disorder[s], may have side effects and consequences.”

(The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Moujaro.)

Not everyone agrees that an eating-disorder history should automatically exclude a patient. Clinicians who specialize in obesity medicine, such as Jesse Richards at the University of Oklahoma in Tulsa, argue that the benefits may outweigh the risks for some patients. “I would say that it would be very important in patients with a history of disordered eating to monitor them, but that the potential health benefits may outweigh the risks in patients that these medications are being used on label,” he says.

In a statement, Novo Nordisk, developer of semaglutide, said “we recognize that eating disorders are serious conditions and deserve specialized clinical attention from healthcare who treat them. Patient safety is our top priority at Novo Nordisk. We stand by the safety and effectiveness of our GLP-1 medicines when used as prescribed and work closely with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to continuously monitor the safety profile of our medicines.”

Eli Lilly, maker of tirzepatide, similarly stated, “Mounjaro and Zepbound (tirzepatide) are indicated for the treatment of serious chronic diseases. Lilly does not promote or encourage use of any Lilly medicine outside of its FDA-approved indication.”

GLP-1 drugs and binge eating

While some people with disordered eating over-restrict, others can binge to deal with stress or difficult emotions. Amanda Lightbody, founder of The Rainbow Crosswalk, a nonprofit Pride organization in New Brunswick, Canada, remembers using food as a child to calm herself down during moments of anxiety or uncertainty. Between 0.6 and 1.8 percent of women and 0.3 and 0.7 percent of men worldwide are estimated to meet the criteria for the disorder.

As she got older, Lightbody sought treatment after her bingeing began affecting her health. “When my medical results started coming back with liver issues, I said, ‘Okay, I need to stop this, and I need to find help, because I cannot do it on my own.’” In addition to therapy, she was also prescribed Ozempic to bring her blood sugar down.

Cognitive therapy helped identify triggers, but she says Ozempic also reduced her urge to binge. “The drug provides me a feeling of satiation, so I don’t crave as much,” she says.

(Mindful eating vs. intuitive eating: Which one is right for you?)

Clinicians are noticing similar patterns. “People would just say their craving, specifically, for highly processed, oily, super salty, super sweet foods… just dropped off,” says Richards.

In 2023, Richards and his colleagues published a comparison between patients taking semaglutide and those using lisdexamfetamine and topiramate, a combination medication already approved for binge eating or weight loss. Those on semaglutide had lower binge eating scores, with fewer binge episodes and less feeling out of control around food. GLP-1s are not currently approved for binge-eating, though there are some clinical trials in progress.

Stopping bingeing, however, doesn’t necessarily mean a binge-eating disorder is cured, says Malin Mandelid Kleppe, a nutritionist at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway. She recalls a patient who had long struggled with bingeing but told her after starting a GLP-1 medication, “I cannot manage to binge anymore. So, it’s actually no longer a problem.”

But while the GLP-1 was treating the bingeing itself, it wasn’t treating the underlying psychological disorder. “She said, ‘When I know there will be a difficult and stressful time in my life, I [have] stopped taking these medications for a while, to binge to handle my life,” Kleppe says. “So, this was very surprising to me, but it told me two things. One, GLP-1s may have treated her binge eating, [but] two, her binge eating has a function.”

It was a single case, but it piqued Kleppe’s curiosity. She is currently running a clinical trial to compare GLP-1 treatment for binge eating with behavioral therapy. She is concerned that treating bingeing alone might not address that people overconsume for a reason—they are trying to cope.

“Studies on bariatric surgery patients have found [that] for some people, increased alcohol consumption and increased self-harm,” she says. So far, studies show GLP-1s may reduce alcohol consumption and drug use, and that there is no difference in risk of suicide or self-harm. But Kleppe wants to know if people find other harmful ways to cope. In other words, the bingeing may temporarily stop—but life and its stresses continue.

Providing care beyond body size

Patients on GLP-1s may have different vulnerabilities, and clinicians have different philosophies about how safe the drugs are—and who should receive them. There’s a spectrum, says Aaron Keshen, a psychiatrist at Dalhousie University and Nova Scotia Health in Canada. On one end are clinicians who treat eating disorders that see “restrictive eating in any form [a]s pathological.” They may refuse to prescribe GLP-1s to patients with even a distant history of disordered eating.

On the other end are some obesity specialists who view weight loss as the most important medical outcome. “The perspective tends to be obesity has consequences, both physical and psychological consequences, and weight loss is the solution.” That mindset might downplay the potential side effects.

Those side effects are very real, Turner says. GLP-1 drugs slow digestion and blunt appetite, and for some people that means persistent nausea, rapid fullness, or a loss of interest in eating altogether. In Turner’s experience, “living on these products is not fun. It takes some joy out of life.” While these medications might help people achieve control, “you’re not addressing any of the relationship with food,” she says. “You’re putting a big old Band-Aid on people’s food issues in a very chaotic world full of trauma. Right now, who doesn’t need comfort?”

Keshen has been working to bring together patients, eating disorder specialists, and obesity medicine experts to reach an agreement on how best to prescribe GLP-1s to those who need them, while ensuring vulnerable patients are safe.

“My perspective is that the truth lies somewhere in the middle,” Keshen says. “I think healthcare prescribers need to be aware of the unintended consequences of GLP-1s…but I also think it’s gone too far on the [eating disorder] end where there’s almost a perspective of GLP-1s are bad in almost any circumstance.” The trick, he says, is to support patients in getting the care they need in the safest way possible.

Part of that would be making sure every patient seeking a GLP-1 drug is screened for an eating disorder and monitored to ensure they’re eating enough, maintaining their health, and not losing weight too quickly. “In certain busy clinical settings, there’s limitations to what clinicians can do in terms of screening and monitoring,” he says. “But there are some very basic and quick things that anybody should be able to do to at least have some degree of monitoring in place.”

Without that screening, Turner says, clinicians may never realize how many patients are vulnerable. “The rate at which the medical community is giving out these drugs tells me that we’re hitting a lot of people with a predisposition for eating disorders.” Turner hopes that clinicians prescribing these drugs will take screening for eating disorders seriously and recognize that people can have eating disorders at every size. “There is a whole life on these drugs beyond what you’re seeing in the office.”