This little-known type of fat may actually protect your heart

A new mouse study suggests that "beige" fat surrounding blood vessels can send calming signals to the arteries—revealing an unexpected biological link between fat tissue and heart health.

Too much fat in the body is associated with a host of negative effects, including high blood pressure—or hypertension—a condition that plagues nearly 50 percent of U.S. adults. It’s easy to assume that less fat is always a good thing. But the effects of fat aren’t so black and white. They are, instead, white, brown, and beige.

In a new mouse study, researchers found that beige fat cells nestled around certain blood vessels appear to send signals that help arteries relax, keeping blood pressure lower.

The findings, published January 15 in Science, also showed that humans with some genetic variants in beige fat cell expression are more likely to have high blood pressure, suggesting that this specialized fat tissue—and the chemical signals it sends—could one day inform new treatments.

Not all fats are created equal

Biologically, fat tissue isn’t a single entity. Instead, scientists consider it an endocrine organ, a collection of distinct cell types sending hormonal signals to the body.

“The public kind of thinks about fat tissue in general as being something that’s nasty,” says Patrick Seale, a biologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia who was not involved in the study. “It’s actually quite the opposite.” Fat tissue both stores and burns energy. It can also increase or decrease the amount of energy the body uses, or its metabolic rate. “It’s not really having the fat tissue that’s a bad thing,” Seale says. “It’s having fat tissue that doesn’t work very well.”

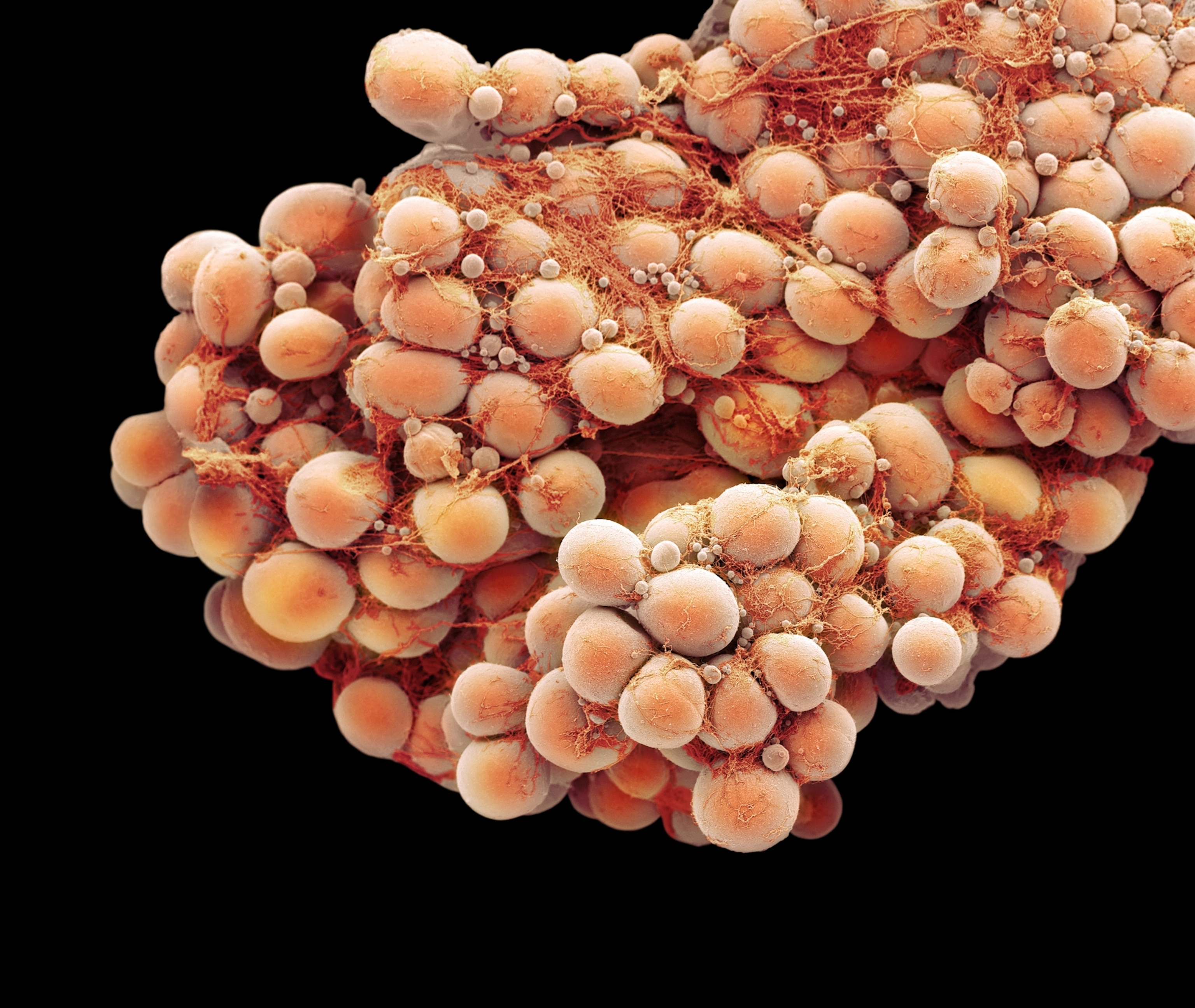

Adipose (or fat) tissue can be divided into three major cell types. White fat cells store excess energy and release it on cue. This is the fat that forms pads under the skin and around internal organs. “White fat is generally in kilogram quantities,” says Paul Cohen, a cardiologist and scientist at The Rockefeller University in New York City. Too much white fat is associated with high blood pressure.

(What is brown fat—and how does it control obesity.)

By contrast, “an adult human might have a few 100 grams of brown fat,” Cohen says, usually located around the neck and collarbones. This fat type is thermogenic—it creates heat and burns energy. People with more brown fat have lower odds of hypertension—even if they are in larger bodies.

Then, there’s the third kind of fat, known in mice as beige fat. These fat cells can store energy like white fat under some conditions and burn energy like brown fat under others. In humans, this type of fat is called inducible brown fat. These cells are interspersed with white fat and are found in cushions surrounding some of the body’s largest arteries.

From human to mouse

The project began with a clinical observation. Cohen had noticed that his patients with more brown fat were less likely to have high blood pressure. To understand why, he teamed up with researcher Mascha Koenen, also at The Rockefeller University. In mice, the identity of beige fat cells is controlled by a protein called PRDM16. The scientists used a mouse model in which they could disable this protein, effectively eliminating beige fat and converting the fat surrounding the animals’ arteries into white fat.

(Fat cell number is set in childhood and stays constant in adulthood.)

Without their beige fat, Koenen says, the animals’ blood pressure increased. They also produced more angiotensinogen, a precursor to the hormone angiotensin II, which powerfully constricts blood vessels, raising blood pressure. “And we did find that these arteries specifically had a hypersensitivity to angiotensin II,” Koenen says.

The team also focused on an enzyme regulated by beige fat called QSOX1. In humans, gene variants in QSOX1 are associated with blood pressure differences. In mice, beige fat-deficient animals showed elevated QSOX1 levels and developed high blood pressure. But when the scientists developed mice lacking beige fat cells or QSOX1, their blood pressure remained normal, suggesting that the enzyme plays a key role in beige fat’s effects on the arteries.

From mouse to human

To see whether the same biology might apply in people, Cohen, Koenen, and their colleagues turned to banks of human DNA. Examining the genes of more than 200,000 people in the United Kingdom’s BioBank and in the Mount Sinai Million Health Discoveries Program, they showed that people with gene variants in their PRDM16 gene were more likely to have high blood pressure. And in reviews of more than 1700 heart echocardiograms, they found that people without brown fat had larger left ventricles—a sign of long-term high blood pressure.

Scientists knew that fat cells were hugging close to blood vessels, Seale says, and that beige and brown fat protected against hypertension. But how fat might directly affect the blood vessels had been a mystery. “This is really one of the first demonstrations that there's actually an important role for that tissue and that it's likely to be clinically relevant,” he says. “I think it's very exciting.”

(The groundbreaking promise of “cellular housekeeping”.)

The study offers a new pathway that can increase or decrease blood pressure, which provides new targets to help control it, says Kazutaka Ueda, a cardiovascular molecular biologist at the International University of Health and Welfare in Japan who was not involved in the study. He also noted that the effects differed by sex. The most substantial impact of beige fat on blood pressure was in male mice, while female mice were protected.

While the findings could eventually help scientists develop drugs, they also show that fat can have positive effects on other organs. “What I think is really exciting is this communication between the different organ systems,” Koenen says. “The adipose tissue talks to the vasculature.” When that fat tissue is beige, its messages could have a soothing effect.