The surprising way doomscrolling rewires your brain

Experts say graphic images, nonstop outrage, and the 24/7 negative news cycle don’t just upset us—they alter our stress response and harm mental health.

The first time Roxane Cohen Silver noticed the media may be psychologically damaging was in 1999. She had been in Littleton, Colorado, conducting research on the Columbine High School shooting when she observed an alarming trend—many of the parents and students she spoke to found it exceedingly difficult to cope with the journalists who interviewed and filmed them just hours after the tragedy.

But it wasn’t until the 9/11 attacks that Silver, a professor of psychology, medicine, and public health at the University of California, Irvine, began to understand just how harmful the media could be. She discovered, after tracking people for three years, that the more people engaged with news about the terrorist attacks, the more likely they were to report mental and physical health problems over time.

Two decades later, there’s now ample evidence showing that brutal news cycles can wreck the body’s stress response and lead to an onslaught of psychological issues in the days, weeks, months, and even years to come. Here’s why.

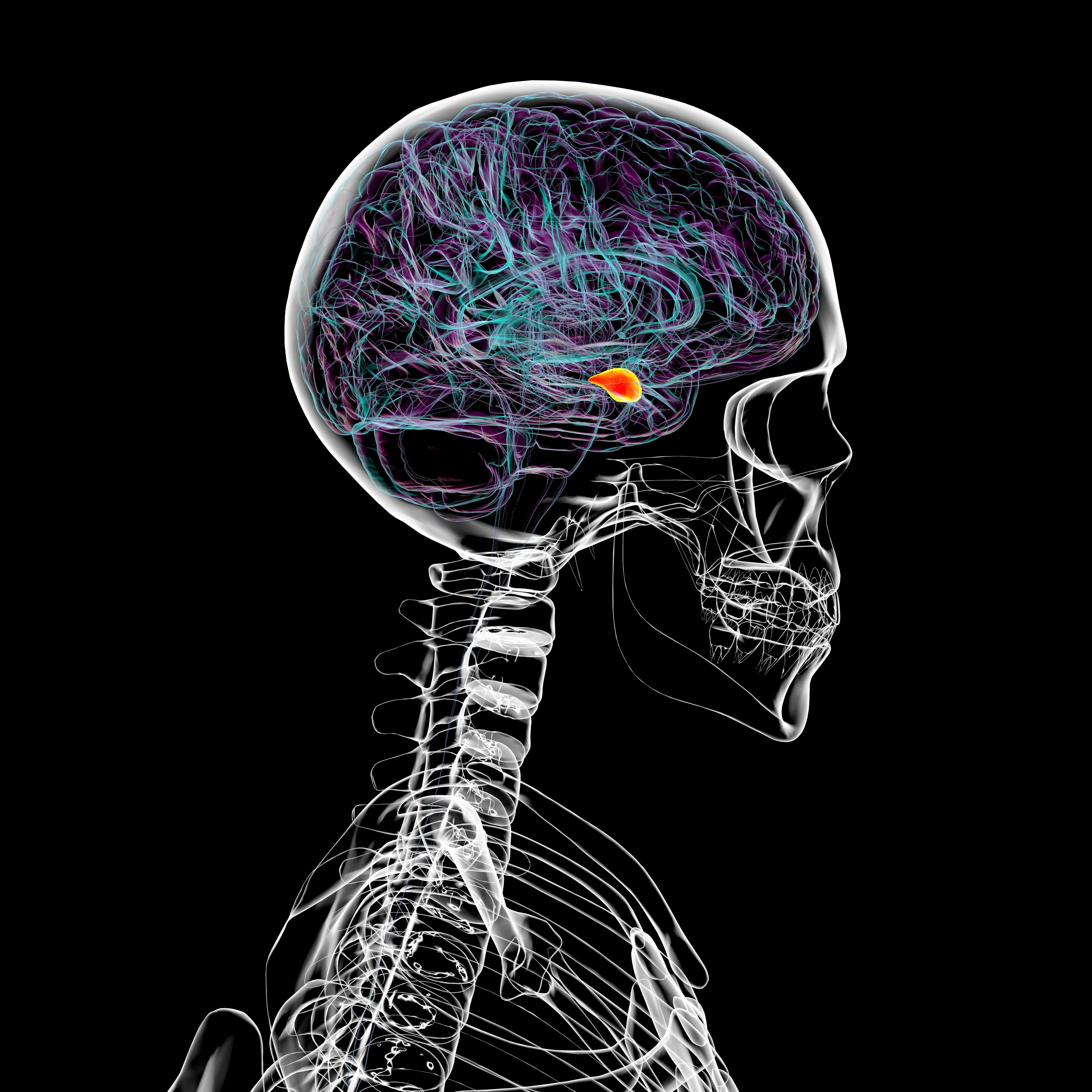

The news activates your stress response

Humans are wired to pay attention to threats, says E. Alison Holman, a UC Irvine health psychologist who has collaborated with Silver for years. Thousands of years ago, that vigilance helped us survive predators like bears or mountain lions. Today, the same instinct pulls our eyes to alarming headlines.

When you see a threat (in real life or through a screen), your fight or flight response turns on and your body releases cortisol and adrenaline, two hormones that provide you with the energy and mental acuity to take on said conflict.

(Endless scrolling through social media can literally make you sick.)

When the threat’s gone, your body returns to baseline. But repeated exposure keeps the system switched on, says Sara Jo Nixon, a professor of psychiatry and psychology in the UF College of Medicine. Over time, this constant activation wears the system down, disrupting both the stress response and the brain’s reward system.

The effects ripple through daily life. Things you once loved, like your friends or hobbies, become less appealing, Nixon says, and you may feel increasingly fatigued, hopeless, and anxious. “This can really impact your entire quality of life and ability to function,” Nixon says.

Indirect exposure to traumatic events can trigger symptoms of PTSD

After Silver’s 9/11 study, she investigated the aftereffects of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. By then, social media was widely used and gory images of limbs blown off were suddenly all over people’s minifeeds. “We had never seen anything like that before,” Silver says. Unlike traditional newspapers or broadcast news, there’s little monitoring or editorial oversight regarding what is or isn’t shared on social media—anything goes.

In studying the bombing, Silver and Holman uncovered two striking patterns. First, people who viewed more violent imagery were more likely to report post-traumatic stress symptoms—nightmares, hypervigilance, emotional numbness—six months later.

Second, individuals who consumed over six hours of media per day reported more acute psychological symptoms, like unwanted dreams, difficulty sleeping, and intrusive memories, than those who were actually at the bombing. “That’s what was so remarkable about those findings: people who were at the site of the bombing had less stress than the people who engaged with excessive amounts of media,” says Holman.

Studies on other disasters—the COVID-19 pandemic, racial violence, hurricanes, the Ebola outbreak, and the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami—have similarly found that when people watch distressing news, their stress levels soar and their well-being suffers—both in the moment and the future.

Repeated exposure also drives the brain into a loop of rumination, Silver’s team found. Each disturbing headline or image reactivates the trauma, forcing the mind to revisit it again and again. For those directly on Boylston Street, the acute event ended once they left the scene. For those glued to screens, the trauma never stopped.

The steady stream of bad news traps us in the trauma

After the Boston Marathon bombing, Silver wanted to know: who is most likely to turn to media during traumatic events? To find out, she and her team investigated the coverage of the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, FL. What emerged was a self-perpetuating cycle. People saw a disturbing story, felt distressed, clicked on more headlines, and grew even more distressed, Silver says.

This cycle can (and does) affect everyone, but those who relate to the victims’ identities or are already prone to fear and anxiety appear to be even more at risk for getting sucked in. Then, in an effort to mitigate their anxiety, they become hyper-vigilant about future threats. “You start constantly worrying about whether something bad will happen again,” Holman says.

This, in turn, boosts the likelihood you’ll go straight to the media when the next disaster strikes and get pulled in all over again, Silver says. “It’s almost like a cycle one can’t break from,” she says. You may know this as doomscrolling.

Here’s how back-to-back stressors affect us

Since Silver first began her research, the media landscape has transformed. Today, a constant stream of headlines pours through the phones in our pockets, delivering bad news at any hour. On social media, the imagery is more graphic than ever, Holman says—and algorithms ensure that once we click, we’re shown even more of it.

(”Urgency culture“ might lead you to burnout. Here’s how can you combat it?)

The year 2020 revealed just how harmful terrible news cycles can be. There was the pandemic, an economic recession, race-driven social unrest, and weather-related disasters. Recent years have been no different: wars in Gaza and Ukraine, political upheaval, mass detentions, floods, and hurricanes have kept audiences locked in a cycle of crisis.

“When event upon event upon event occurs, your body cannot regulate itself,” says Holman. The evidence is undeniable—these compounding traumas broadcast across multiple platforms are harming us psychologically.

How to mindfully consume the news

It may feel impossible to follow the news without feeling overwhelmed, but researchers say a few simple habits can help.

Holman recommends first taking a deep breath before you whip out your phone or turn on the TV. Take note of how your body’s feeling. Then, as you scroll, keep deep breathing (it will keep you relaxed and connected to your body) and take stock of yourself. If you become tense, your heart rate increases, or your shoulders tighten, pause for a moment. These signs indicate the news is triggering your stress response, and it’s time to step away, says Holman.

(Here’s what happens to your brain when you take a break from social media.)

Everyone has a different threshold; some people may be able to engage for 15 to 20 minutes; others may burn out after five. “You have to know what works for you,” says Holman. Don’t play on your phone throughout the day, she adds. Instead, choose one or two designated windows to catch up on the news and set a timer. “You need to give your brain and your body a break,” says Nixon.

Finally, follow Silver’s lead. She avoids graphic images at all costs because she knows how destructive they can be. When she’s reading a story about, say, Gaza, she puts her hand over the disturbing images. This protects her psychologically, she says, while allowing her to stay up-to-date on world events. “I take my research quite seriously in my own life,” she says.