Scientists identify 4 key turning points for your brain as you age

New research has charted the major developmental stages in the brain’s wiring—from early-life pruning to late-life network breakdown—offering a new roadmap for how our brains evolve.

It’s no secret that our brains change as we age. The ease with which we form new connections—whether learning a language or picking up a new skill—shifts throughout life. But scientists are now showing just how dramatic and how patterned those shifts really are.

A new study from the University of Cambridge has identified five distinct phases of brain development across the human lifespan. The phases are marked by four turning points: ages nine, 32, 66, and 83, where brain rewiring shifts. “At different points in time, the brain is expected to be doing something different,” says Alexa Mousley, a research associate at the University of Cambridge and lead author of the study. “These phases show that the development of the brain is non-linear.”

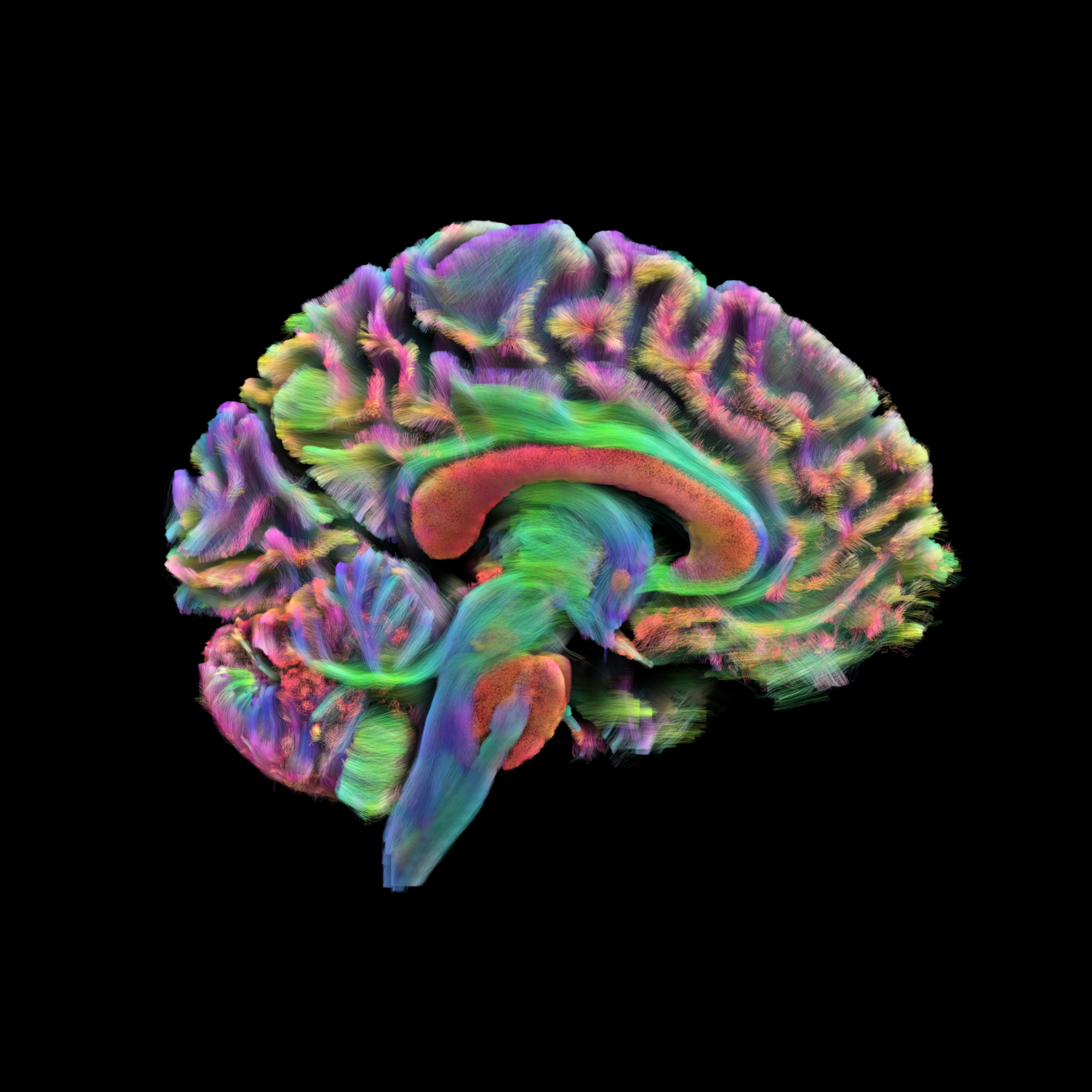

To uncover these stages, researchers studied data from brain scans of nearly 4,000 people to identify where myelin—the fatty insulation that speeds electrical signals along nerve fibers—and the movement of water along those fibers, which helps reveal how different regions connect. “Myelin is basically insulating the connection, making it quicker,” Mousley explains.

By mapping these features from infancy through age 90, the team revealed how the brain’s communication pathways strengthen, stabilize, and eventually decline in recognizable patterns. These patterns may eventually help researchers identify why certain mental health issues develop at specific points in a lifetime and provide a benchmark for evaluating cognitive ability. Here’s what happens inside the brain at each stage.

Infancy to childhood (0-9): How the brain rewires itself

Early childhood is often seen as a period of rapid learning, but the research team found that the brain actually becomes less efficient during this period. Between birth and age nine, the number of synapses—the junction that allows neurons to pass signals—decreases as the child ages. Only the most active synapses survive, a pruning process that helps streamline the brain’s circuitry.

At the same time, white matter, areas where myelin helps transmit signals, and gray matter, areas filled with neurons, rapidly increase. Together, white and gray matter work to facilitate critical cognitive abilities, including learning and memory.

“We know from past work that things like dementia and mental health are related to the way the brain is wired,” Mousley adds. Although the researchers can’t definitively say these wiring patterns are related to mental health disorders that appear in childhood, “It’s a reasonable hypothesis, but hasn't been directly explored yet,” she says.

Adolescence (9-32): When the brain reaches peak efficiency

By the time a person reaches their early 30s, their brain hits a period of “peak” efficiency—regions of the brain are using the most direct pathways to communicate. White matter continues to increase, and connections across the brain follow the most efficient paths.

But, Mousley says, this isn’t inherently better than the other phases: “It doesn’t necessarily mean that kind of the things that are happening in later phases are, quote, unquote bad. It’s just a different point in time.”

Perhaps the most surprising conclusion from the study is that adolescence extends far longer than we typically imagine. Based on how the brain forms and refines connections, this developmental window lasts until roughly age 32.

But this distinction is based on the brain’s efficiency at making connections, not behavior, Mousley notes. “Nothing about our work suggests that you should be behaving like a teenager into your 30s,” she says.

Compared to other mammals, Mousley notes, humans take a long time to reach adolescence. “The idea that we don’t peak until we’re early 30s, that’s a very, very long time,” she says. “We’re seeing that it’s something that sets us apart as humans. There’s some theories that this is why humans are so diverse, that having this development be slow lets us make more complicated connections than other species.”

Adult (32-66): Why the adult brain enters a long plateau

Adulthood marks the longest and most stable stretch of brain development. Researchers found that “there’s no major shift in structural rewiring for those three decades,” Mousley says. “There’s changes happening, but there’s not one that really sticks out.”

(Your brain shrinks after 40. Learning a musical instrument can reverse it.)

Instead, the brain settles into a long plateau: communication pathways hold steady, and the rapid pruning and fine-tuning of earlier years taper off. Other studies have shown that personality and intelligence stabilize during this time.

Early aging (66-83): How the brain’s wiring breaks down

Around age 66, the brain enters a period where its wiring begins to fray. White matter begins to degenerate more rapidly during the early stages of aging.

As a result, the brain’s network becomes more clustered: regions talk efficiently within small, tight-knit groups but communicate less easily across the whole system.“ Segregating into small, well-connected groups—that’s increasing,” Mousley says. This time period has been associated with a higher onset of dementia and hypertension in other research.

Late aging (83-90): When the brain’s network fragments

In the final phase, the brain’s communication network becomes even more fragmented. Mousley likens the late-aging phase to bus routes: Some buses stop running, so trips that once required a single direct line now require multiple transfers.

(The unexpected ways Ozempic-like drugs might fight dementia.)

“What we suspect is happening is that there’s reducing connectivity, and potentially less connections,” Mousley says. “So to get information across the brain through the structural connections, certain regions become very important for that process.”

What these age milestones really mean for your brain

Because this study reflects population averages, these turning points shouldn’t be read as precise milestones. Most won’t suddenly feel a notable cognitive shift on their 66th birthday.

“If you go to your doctor, and you ask for medicine, I don’t want what the average 40-year-old gets,” says Richard Betzel, a neuroscientist at the University of Minnesota who was not involved in the study. “I want something that's tailored to my specific needs. Every individual is not sitting right at that middle point.”

(When does old age begin? Science says later than you might think.)

Still, these ages may serve as useful benchmarks as scientists learn more about which brain connections strengthen or fade during each phase and how those changes relate to learning, personality, and mental health.

“Maybe it's a useful target saying, ‘I’m approaching one of these transitions. Let’s see.’ It forces people who wouldn’t otherwise reflect on their brain health [get] a little nudge to do it,” Betzel says. “So I can see that being a really powerful inadvertent effect of this.”