The curious link between Alzheimer’s disease and cancer

Scientists have long observed that cancer patients have a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease. New research reveals a possible reason why.

In recent years, scientists have been starting to ask themselves this question: What if Alzheimer's disease isn’t simply a disease of the brain?

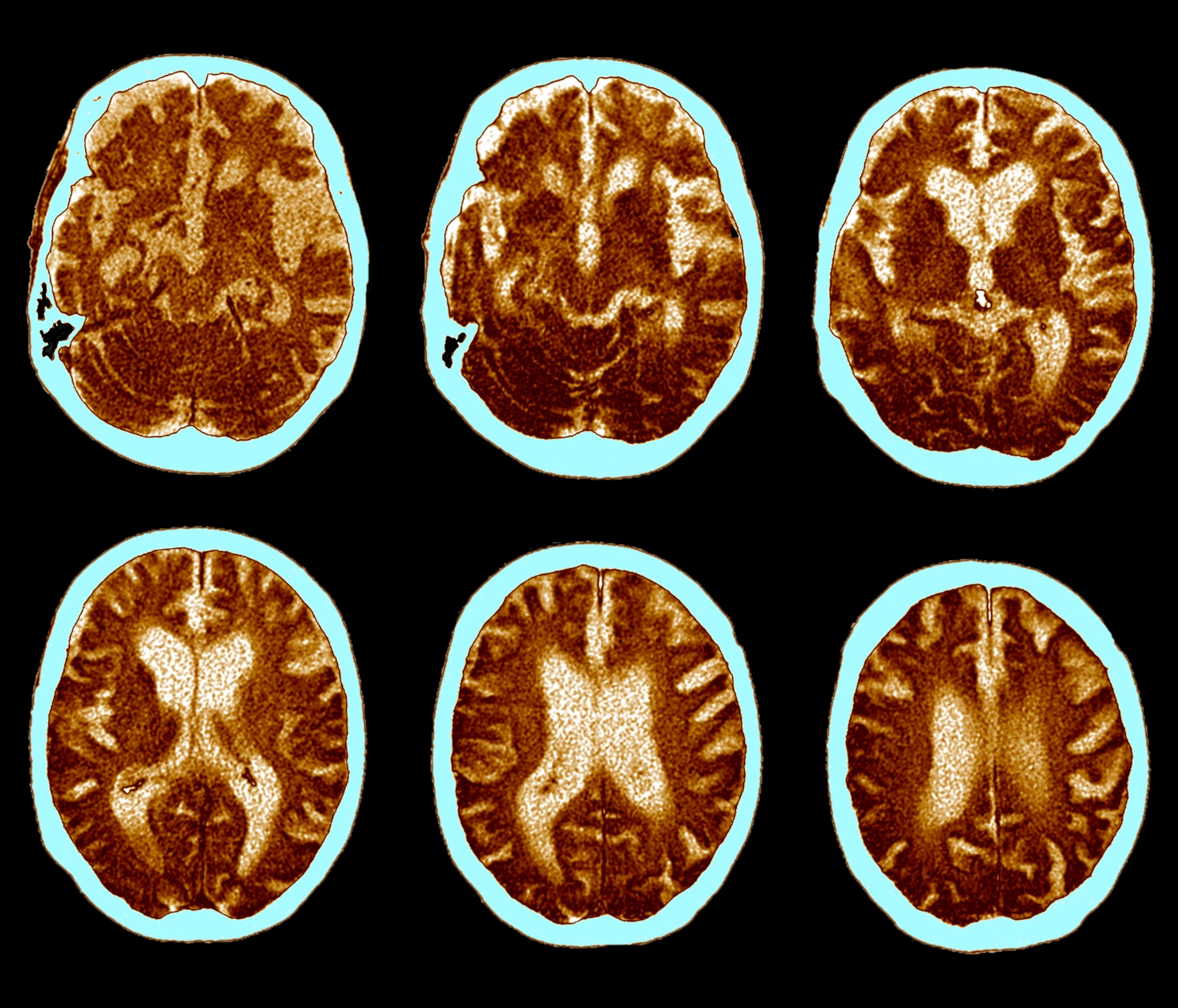

It certainly has always seemed to be. The defining feature of Alzheimer's—the most common form of dementia, affecting millions of people worldwide—is the buildup of proteins that cause amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain. This buildup is then followed by the death of neurons, which causes memory loss, mood disturbances, and behavioral changes.

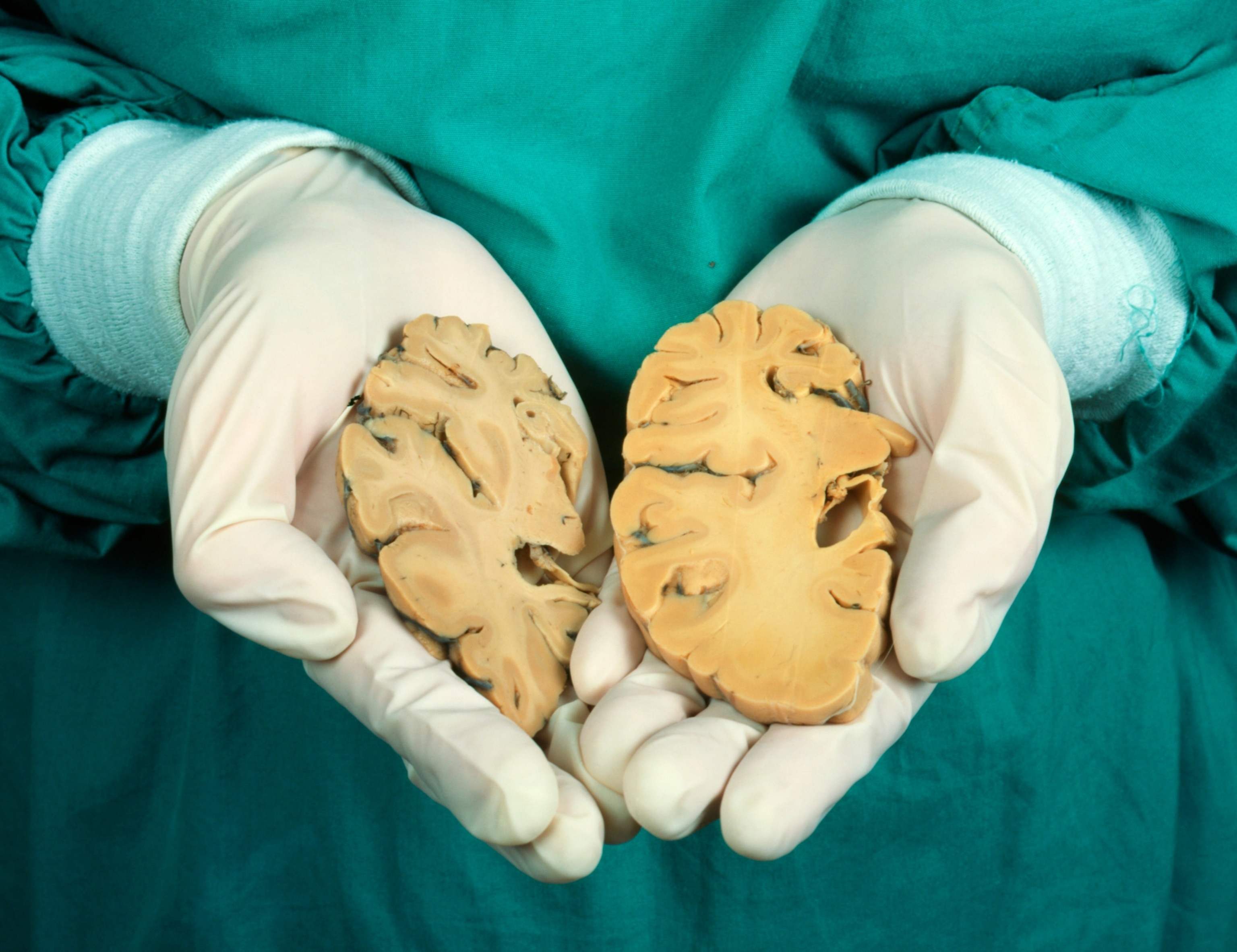

Yet for decades, researchers and physicians have noticed a curious phenomenon, where their cancer patients seemed to have a much lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s, while their Alzheimer's patients tended not to be cancer survivors. This phenomenon has been borne out in a number of epidemiological studies, yet the exact reason for it has always been unclear.

(What are the signs of dementia—and why is it so hard to diagnose?)

In a recent study, published in the journal Cell, researchers found one possible mechanism with the discovery of a shared biological pathway between cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

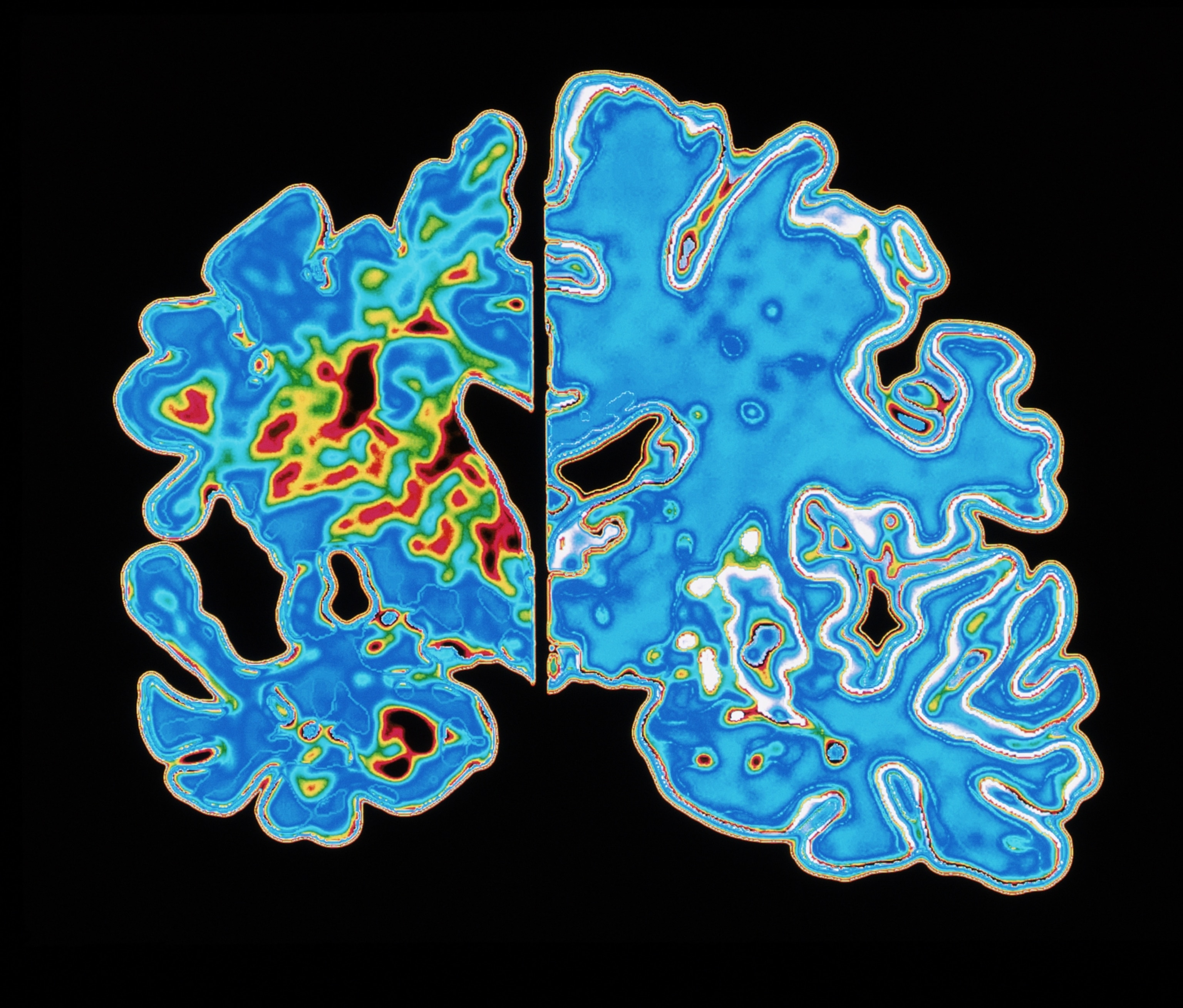

“Cancer and Alzheimer's disease sit at opposite ends of several core biological processes,” explains Jordan Weiss, a longevity researcher in the Division of Precision Medicine and Optimal Aging Institute at NYU Grossman School of Medicine who was not involved in the study. “Too much of something predisposes you to one of those outcomes, not enough of it predisposes you to the other.”

These shared biological processes have to do with the immune system and the way the body clears out proteins to keep them from building up. The new study provides additional evidence that the immune system may play a bigger role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease than we originally thought. “Now we’re seeing Alzheimer's disease […] as a disease of failed immune homeostasis in an aging brain,” Weiss says.

An immune system that’s too active can lead to the death and destruction of neurons you see in Alzheimer’s patients, while too little immune system activity can allow cancer cells to survive. Similarly, clearing proteins too aggressively can destroy proteins that are useful for keeping your body healthy, while not clearing them aggressively enough can lead to the accumulation of proteins in the brain, known as plaques, leading to neuron damage.

A link between cancer and a reduced risk of Alzheimer's

The link between cancer and a reduced risk of developing Alzheimer's has long been observed.

One study, published in 2012, found that cancer survivors had a significantly lower risk of Alzheimer's, while people with Alzheimer's disease had a lower risk of being diagnosed with cancer. Another major study, published in 2024, looked at over three million individuals and found that cancer survivors had a 25 percent reduced risk of developing dementia. A third study, published in 2025, found that APOE disease, a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease, was also linked to a reduced cancer risk.

(Lithium plays a mysterious role in the brain. Could it be used to prevent Alzheimer’s?)

One of the early theories for this phenomenon has been that the process of treating cancer somehow helps prevent the development of Alzheimer's disease. This theory is supported by a number of studies that show the progression of Alzheimer’s disease is linked to changes in immune system activity.

“You give someone chemotherapy to kill a cancer cell, but your immune system is also reduced in activity for quite a while,” which was thought to potentially slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, says Paul Schulz, a neurologist at UTHealth Houston.

However, this new study adds fuel to another theory that suggests the link may have more to do with the biological overlap between cancer and Alzheimer’s disease—and how they interact with the immune system.

Alzheimer's disease and the immune system

For years, Alzheimer’s researchers primarily focused on the characteristic amyloid plaques, convinced that they were the primary cause of the disease. However, as research is showing, these plaques aren’t necessarily harmful in and of themselves, but rather, it’s the immune system’s response to the plaques that damages neurons.

“Some people get Alzheimer's in their 50s, some get it in their 90s, and some people pass away with more amyloid [plaques] in their brain than either of those, and they never develop the disease,” Schulz says. “The hypothesis is that amyloid and tau protein in the brain don’t directly cause neuronal damage, they cause it when your immune system reacts to them.”

As a result, researchers and clinicians are starting to think of Alzheimer's disease as a “disease of dysregulated brain immunity,” Weiss says.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, cancer is also linked to changes in the immune system, as part of the immune system’s job is to scan the body for cells that are dividing too rapidly, and to then dispose of these potentially harmful cells. If the immune system becomes less active, it can lose the ability to identify and dispose of these cancerous cells, leading to the growth of a tumor.

(The unexpected ways Ozempic-like drugs might fight dementia.)

“There are a lot of perturbations in the immune system that are important for cancer and for Alzheimer's, and it makes sense there would be crosstalk between them in that regard,” Schulz says.

But what exactly is that crosstalk? The new study published in Cell “proposes another possible mechanism,” says Ian Grant, a neurologist at Northwestern Medicine.

Molecule linked to cancer can degrade plaques in brain

In the recent study, which was conducted in mice, researchers transplanted human cancer cells into mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. What they found was that the mice with transplanted cancer cells did not develop Alzheimer’s disease. Something about the cancer cells seemed to be having a protective effect. “So then we asked, ‘why’?” Youming Lu, a neurologist at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China, and the lead investigator of the study, told Nature.

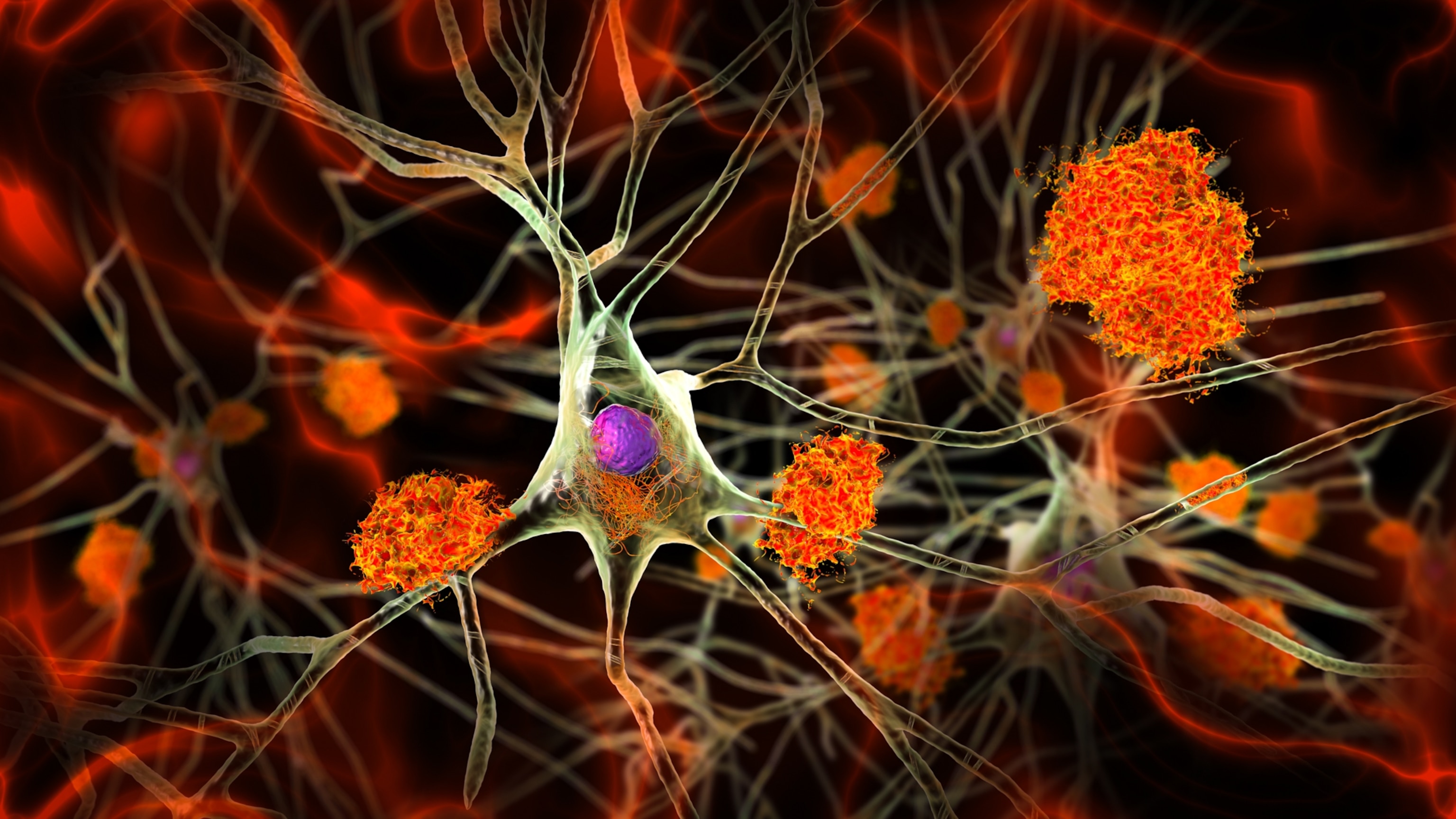

In follow-up experiments, Lu and his collaborators found that the development of tumors is linked to a rise in a molecule called cystatin C, which plays a role in regulating the immune system as well as ensuring the removal of built-up proteins. In turn, the study showed that cystatin C activates a molecule in the brain called TREM2, which can help dissolve amyloid plaques.

(Your eyes may be a window into early Alzheimer's detection.)

These results could explain the link between cancer and a reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease, however the finding will need to be validated in further studies. This includes studying whether the pathways are similar in humans, and identifying the ways in which this pathway overlaps with other processes. These results will also need to be replicated.

“It’s a great finding,” Schulz says, adding that “there’s a precedent for what’s going on in this paper.”

Identifying a new potential mechanism could help yield additional insight about Alzheimer's disease, while also suggesting possible therapeutic targets. Research results like this “force me to reconsider bold, new ideas that might play a role in this disease,” says Kumar Narayanan, a neurologist at the University of Iowa Carver School of Medicine.

However, as experts also caution, although these results are interesting, we are still a long way away from having these results translate into new therapies for Alzheimer's disease. “It doesn’t mean that cancer is protective, and it certainly doesn’t mean that anyone should view cancer as beneficial, in terms of staving off Alzheimer's disease,” Weiss says.