Childbirth is still too dangerous. This ancient profession can help.

Midwives are making a big comeback, and solving a crisis in maternal health care.

It’s 5 a.m. at Mother Health International (MHI), a birth center in Northern Uganda affiliated with Yale University, when the call comes in from a local midwife about 12 miles away. A woman in her village has gone into labor. The alert sets a series of gears into motion: a motorcycle driver is immediately dispatched to zip down the mostly unpaved roads to her location, while the nurse midwives at MHI prepare a room for labor and delivery. Within an hour, the laboring mother and her local midwife arrive at MHI where she’s greeted by nurse midwives who work together to ensure a safe delivery. An ambulance stands ready in case the birth becomes difficult, but it isn’t needed. Soon, the room celebrates: a new baby is welcomed into the world and placed onto her mother’s chest.

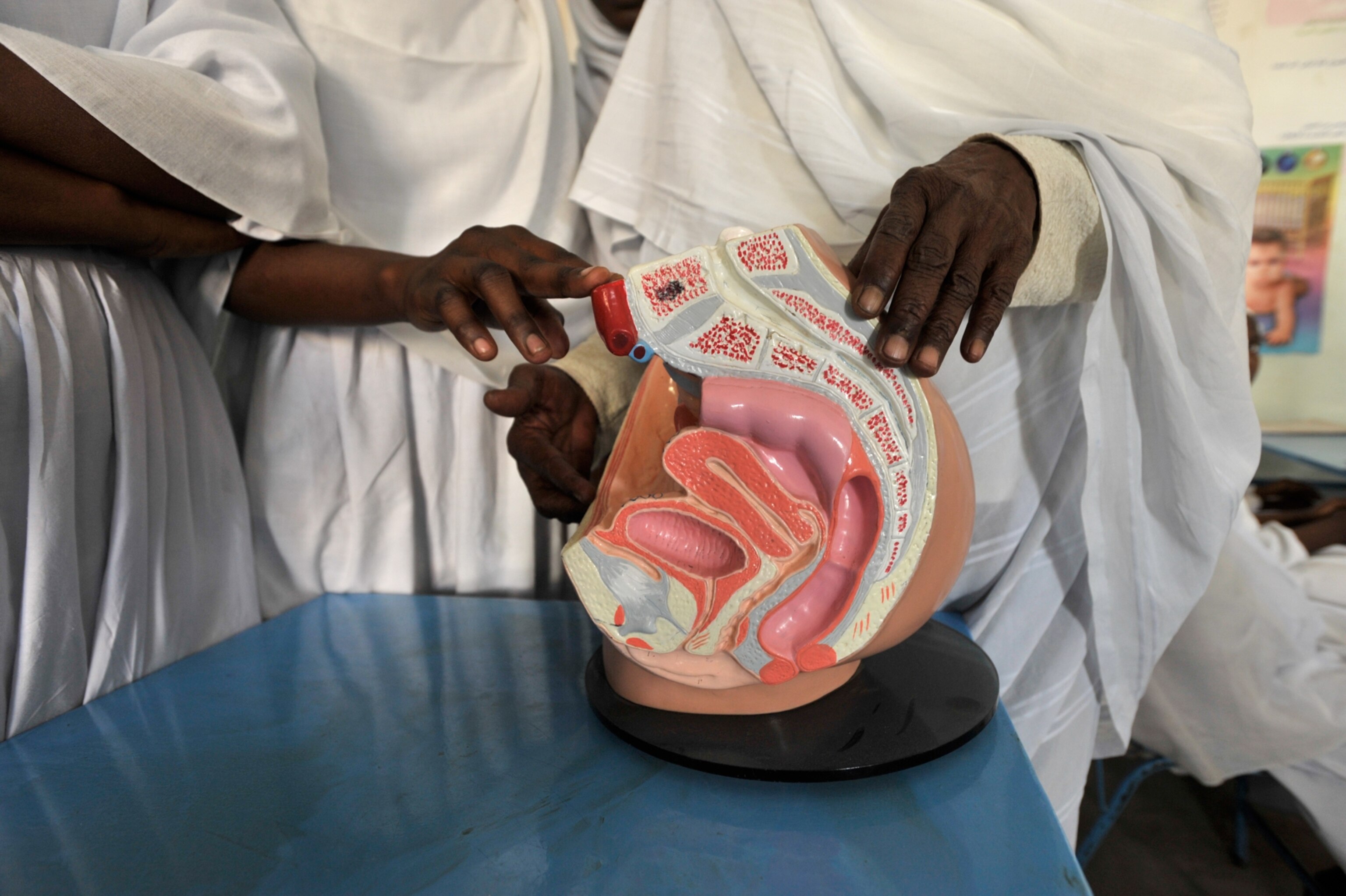

Midwife Rachel Zaslow, the executive director of MHI, has been in this situation many times. During her nearly 20 years at the center, Zaslow has seen the near-miraculous transformation in care for Uganda’s pregnant women. When she arrived in 2006, up to 30 women might deliver babies daily in a worn-torn hospital with a single midwife. Now, MHI’s highly effective model, called the Framework for Quality Maternal and Newborn Care, facilitates collaboration between traditional midwives in local communities and certified nurse midwives. The results are impressive.

Healthy and safe births are commonplace at MHI, which has assisted with over 20,000 births since 2007. Zaslow says they have never lost a mother. That, she adds, is “extremely rare” in East Africa, and the rest of the world. Since implementing their model, the maternal mortality rate has dropped significantly, representing over 60 maternal lives saved.

Could the United States, which has a maternal mortality rate much higher than other wealthy nations, benefit from MHI’s midwife-centric approach to maternal care? Research suggests that it could.

In the U.S. the overall maternal mortality rate is 18.6 per 100,000 live births; for Black women, the figure is even higher at 50.3 deaths per 100,000 live births, worse than MHI’s numbers, a statistic Zaslow describes as “alarming.” Plus, in the U.S., the maternal mortality rate has been climbing—it’s already the highest among high-income countries—and experts anticipate that rate to rise for a variety of reasons, including patchwork maternal care that fails many, as well as medical discrimination that disproportionally impacts Black, Native American, Hawaii and Pacific Islanders.

According to a recent article in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, midwife care (which includes prenatal, labor and delivery, and postpartum care in settings such as hospitals and birth centers) can lower mortality rates as well as lead to fewer preterm births and low birthweight infants as well as reduced interventions, like C-sections, in labor. The authors note that although midwifery is growing, midwives attended just 10 percent of births in the U.S. in 2020.

And in low- and middle-income countries, 82 percent of maternal deaths could be prevented by scaling up midwifery care, according to an estimation tool developed by the Institute for International Programs at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. More recently, a 2025 systematic review in BMC found that midwifery significantly improves maternal and newborn health in low- and middle-income countries while also lowering newborn mortality and morbidity.

In late 2024, the World Health Organization published a position paper that echoed the benefits of a midwifery model of care, noting that it leads to more equitable outcomes and declining numbers of maternal mortality. Given the evidence, it’s no surprise that more women are turning to midwifery, looking for solutions to the country’s fractured maternal healthcare system.

“I think patients have read a lot about the gaps in the U.S. maternal health model and they're looking for better experiences and more modern versions,” says Anu Sharma, founder of maternal health start-up, Millie.

As a result, one of the oldest forms of person-to-person medical care is experiencing a renaissance—and the field is expected to grow significantly over the next decade. “We're bringing ancient wisdom back into the modern era,” Sharma says. This is a revolution of what was once the norm: person-to-person care that treats childbirth as routine while leveraging medical advancements and technology as needed.

The long history of midwives

Midwifery is by no means new; the system of women caring for women is mentioned in ancient texts and books authored by midwives’ date to the Renaissance. In early America, Black midwives who survived the Middle Passage brought their skills with them, practicing midwifery while enslaved. Known as granny midwives, these women delivered the infants of fellow enslaved women as well as the wives of their white owners. But midwifery practically disappeared in the United States at the close of the 19th Century as hospital births became the norm.

Though the transition from home to the hospital was made in the name of safety, it dramatically increased maternal mortality rates. That was “due to poor practitioner training, excessive interventions, and the failure to implement aseptic techniques, says Carol Sakala, who leads maternal health and maternity care programming at the National Partnership for Women & Families, a non-profit, non-partisan advocacy organization.

Maternal mortality rates, however, declined after 1920, due in part to public health advances and the development and use of antibiotics and aseptic clinical standards from the late 1930s as well as access to maternity care and safe and legal abortion.

“In the 20th Century, hospitals and doctors rose to the fore, gained a lot of power and control and systematically denigrated and displaced long standing birthing traditions, including midwifery care,” says Sakala, adding that there were campaigns to eliminate Black granny midwives and immigrant midwives along with their knowledge and cultural practices. According to Keisha L. Goode, PhD, Assistant Professor, Sociology at SUNY Old Westbury, anti-Black racism is “deeply intertwined with the story of midwifery.”

“The field of medicine essentially destroyed midwifery and took it out of the hands of women [and] significantly medicalized it,” says Dana R. Gossett, an OB-GYN and chair of the obstetrics and gynecology department at NYU Langone Health.

As a result, traditional methods of labor and delivery were replaced with medicalized intervention, both for the better and worse. While they are now considered emergency procedures, in the 60s and 70s it used to be common for doctors to perform episiotomies (i.e. surgical cuts between the vagina and anus) under anesthesia, and to pull infants out forcibly with forceps. Each resulted in enduring complications. Forceps can cause severe perineal tearing or injury to the newborn while episiotomies leave new mothers with severe pain and longer recovery times. Women eventually resisted these practices. Gossett points to the mainstreaming of Lamaze in the 60s as one of the earlier notable pushbacks against hyper-medicalized births.

“Lamaze is a specific form of childbirth preparation that uses breathwork and focus to manage the pain of contractions,” Gossett says. Women, she says, were “attempting to take back control of the birthing process from male physicians.” By midcentury, midwives started to resurge. “[When] I was born […], my mother took Lamaze classes and had a natural childbirth,” Gossett says.

Ina May Gaskin, often referred to as the “mother of midwifery” founded The Farm, a Tennessee community focused on providing midwife care and training future generations, after a traumatic birth where a physician used forceps, in 1971. Shortly after, she published Spiritual Midwifery, a landmark book that advocated for home births and breastfeeding.

In the next few decades, Gossett says that out-of-hospital births and the percentage of women using midwives began to increase.

Solutions for a “broken model of care”

In December 2019, Jillian Perez was lying in a medical gown on the table in her OB-GYN’s office for her first prenatal visit. She felt “like a number,” she remembers, as though her pregnancy was a problem to solve, rather than a natural process. “It just didn't jive with how I wanted my pregnancy to be treated and to go,” Perez says. “I want to be talking to somebody who I know and trust.”

Perez isn’t alone, and science tells us that this kind of bond with a midwife has documented health benefits for mothers and children. “When people feel safe and cared for, the hormones of labor work well, says Michelle Telfer, MHI midwife and Associate Professor of Midwifery & Women's Health at Yale School of Nursing. Research Telfer co-authored supports that women have better outcomes, including lower preterm birth rates, when they know their midwife and they have continuity of care with that midwife.

Plus, the personal, one-on-one care midwives traditionally offer can help with overcoming implicit bias, or attitudes that unconsciously affect behavior, that contribute to higher mortality rates among minority groups. Indeed, research published in JAMA states that implicit bias of physicians has been associated with false beliefs that Black patients have greater pain tolerance than white patients. Telfer, however, stresses that building relationships is key to overcoming this bias.

After her second appointment with an OB-GYN, Perez went to a local midwifery practice on the recommendation of a friend. “Immediately it felt so different,” Perez, now a mother of three, says. “I just felt like I was listened to, and my pregnancy was being treated as a normal thing that happens, and your body knows what to do.”

Sharma also experienced firsthand how different a medicalized hospital birth is compared to one that’s overseen by a midwife. In August 2019, during her third trimester, she developed gestational hypertension and had an early induction, which set off a two-and-a-half-day long labor and, ultimately, an unplanned C-section. Like nearly all new mothers, she was sent home with instructions to come back in six weeks. She ended up returning to the hospital 36 hours later with self-diagnosed postpartum preeclampsia, a condition that develops when blood pressure spikes dangerously high.

“I showed up literally on the verge of a stroke, and I saved my own life,” she says. “What I had already begun to sense as a patient […] became a full-blown realization that our care model is completely broken.”

In response to what Sharma describes as the “one size fits all” approach to pregnancy, she started building Millie in 2020. The maternal health startup combines obstetric and midwifery services that women can access in clinics and virtually. An app that provides stage-relevant content, care team messaging, and other resources, as well as remote monitoring tools. “It was just very much a pissed off mom who was trying to build a better experience,” she says. But Millie isn’t the only startup capitalizing on the midwife renaissance: Oula and Pomelo Care are both invested in rethinking women’s health.

A growing number of midwives

The percentage of births attended by midwives was 10.9 percent in 2022, up from 7.9 percent in 2012, according to the American College of Nurse-Midwives.

But it could be poised to grow exponentially, in part due to sheer need: According to 2021 projections from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, demand for OB-GYNs could exceed supply by 2030. That’s particularly true in rural areas where pregnant women must increasingly travel to get care, says Holly Kennedy, a nurse midwife and the Helen Varney Professor of Midwifery Emerita at Yale School of Nursing. Since 2010, over 500 rural hospitals have closed their labor and delivery wards and more are poised to close in the near future.

Kennedy only discovered midwifery herself “by the luck of the draw” during an internship in the early 1980s. She was so impressed by the midwives, she decided to go back to school to become one herself. Today, she’s passing on her knowledge to the next generation of midwives at Yale as a professor of midwifery and researcher.

Now, there are many routes to becoming a midwife. Nurse midwives, certified by the American Midwifery Certification Board, are registered nurses with a master’s or Ph.D. in midwifery. They have full prescriptive privileges and offer reproductive care from prenatal to birth to menopause. There are also midwives certified through the American Midwifery Certification Board without nursing degrees but who can operate in a similar manner, as well as professional midwives who are certified through the North American Registry of Midwives for non-hospital births. And then there are traditional midwives and doulas, who aren’t formally licensed but can play a vital role in the birth process.

According to the Commonwealth Fund, integrating midwives into health care systems could potentially avert 41 percent of maternal deaths, 26 percent of stillbirths, and 39 percent of neonatal deaths.

The benefits of a midwife model of care

Using a midwife doesn’t have to mean forgoing a doctor. At medical centers like NYU Langone’s Joan H. Tisch Center for Women’s Health, they’re innovating on integrating the two.

On a Thursday evening in May a group of about 50 women mingled over wine and hors d'oeuvres alongside the center’s OB-GYNS and midwives as well as local doulas and lactation consultants. Just last year, the hospital embedded midwifery into its obstetrics and gynecology department, chaired by Gossett.

She arrived at NYU via the University of California, San Francisco, which has a robust midwifery program, and admits that she was “startled” by the “lack of midwifery” at NYU.

“For the vast majority of women, [pregnancy] is a safe and healthy process,” Gossett says.

While physicians can play a critical role in reproductive care, they’re trained to view pregnancy as a disease process, says Gossett. In contrast, midwives treat pregnancy as a natural phenomenon.

“And to the degree that we can let [births] happen naturally. That's what we should be doing,” she says.

That’s why Gossett believes it’s important that the midwife or group of midwives is partnered with a physician group, including high-risk obstetrics. “When things go wrong in labor, they go wrong very fast and they can go very, very badly wrong,” she says, which is why having an embedded midwife practice within a hospital setting is ideal.

“Midwives are frontline maternity care providers in nearly all other nations, but ob-gyns are the dominant maternity care providers in the U.S.,” Sakala says. “Because having a baby is not inherently pathological, this is a deeply irrational situation.” A parallel, she says, would be using cardiologists for routine blood pressure checks who would have a “more interventionist approach” to healthy people.

“There's such a benefit [to a midwife model of care], but at the same time, you want to have an easy transition of care when things get more complicated or [a] patient changes from being a low risk patient to one that's more high risk,” says Joanne Stone, Professor and System Chair of the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

And other major medical centers have embedded midwifery as well—take Northwell Health, New York State’s largest healthcare provider, which has embedded midwifery at some locations, and the Midwifery Program at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, which operates independently but still prioritizes collaboration with physician colleagues.

Reimagining America's maternal healthcare system

Midwifery, Kennedy says, is a potential answer to the perinatal care crisis.

But even though a recent Listening to Mothers survey found that a majority of women said they would want or would consider a midwife, the interest currently “exceeds current levels of availability and use of midwifery care,” Sakala says. Growing pains in the profession will be inevitable since there’s a shortage of teachers in the field. Telfer points out that while doctors’ residencies are funded through the government, that’s not the case with midwifery.

Meanwhile, like all hospital care, the cost of hospital births is rising as much as 20 percent, according to some estimates. The median cost of a healthy vaginal birth in the United States is almost $29,000 (the median cost of a C-section is almost $38,0000). In comparison, midwifery is far less expensive and a more efficient way to deliver care. According to a 2020 case study by the National Partnership for Women & Families, childbirth costs at midwifery-led birth centers were 21 percent lower. “In my mind, this is a perfect moment for us to have grown our midwifery program because they do help us grow in a cost-effective way,” Gossett says.

There are also larger reforms on the horizon: Sakala cites a new model from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services called Transforming Maternal Health as “an immediate catalyst for midwifery.” This 10-year care delivery and payment reform model in 15 states will provide resources and technical assistance that includes requirements such as increasing access to midwifery care and birth centers, Sakala says.

She hopes it will “foster a tipping point for midwifery.” Her personal goal, and one shared by Birth Center Equity, is that 50 percent of births will be attended by midwives by 2050.

Getting there might require a radical rethinking of maternal health in the United States. Goode notes that there are social, structural, and political determinants of health at play, all of which need to be addressed. “We need a big picture, systems re-imagination of the perinatal healthcare system,” she says. Midwifery can, as the evidence shows, be part of that shift, potentially leading to better outcomes for pregnant women and, like MIH in Uganda, significantly lowering the maternal mortality rate.