These drugs could be a game changer for end-of-life care

Certain psychoactive substances can improve the mental health of terminally ill cancer patients—but few patients can currently access them.

Several years ago in Vancouver Island, Canada, a 32-year-old mother with advanced metastatic cancer was so wracked with pain and a fear of dying she constantly wept in bed. Through a targeted Canadian government program, the woman accessed psilocybin, the main psychedelic ingredient in magic mushrooms. The day after taking a dose of the drug she was pain-free, able to joke with family members and reconnect with old friends before she died the following week.

Palliative care physician Valorie Masuda remembers this patient well; her experience led Masuda to grasp the power of psychedelic drugs for people with terminal diagnoses for the first time. The drugs can help with “the existential component of pain that is tied in with spiritual and psychological experiences,” something conventional medicine has few tools to address, says Masuda, a physician with SATA Centre for Conscious Living, who has since facilitated dozens of psychedelic sessions for similar patients.

Some 400 terminal patients in Canada have legally accessed psilocybin in the past five years via its special programs, and several countries already allow for similar uses. Due to federal drug laws, terminally ill people in the U.S. cannot currently take psilocybin outside of a handful of clinical trials.

But this may finally change, as government agencies are evaluating whether to allow its use for end-of-life care—thanks to pressure from physicians and years of research. Many palliative care doctors in the U.S. say the change can’t come soon enough.

The psychedelic medicine does not treat metastatic cancer, end-stage kidney or lung disease, or other terminal conditions, but it often reduces the depression, anxiety, and dread that accompanies them, experts say.

“The facts about their life don’t change, but how they interpret them changes. They are able to tell a full story of their lives, where the illness is no longer the dominant theme,” says Manish Agrawal, a physician and philosopher who is chief executive officer at Sunstone Therapies in Rockville, Maryland, who has overseen psychedelic research in more than 100 cancer patients.

Studies show large and lasting improvements

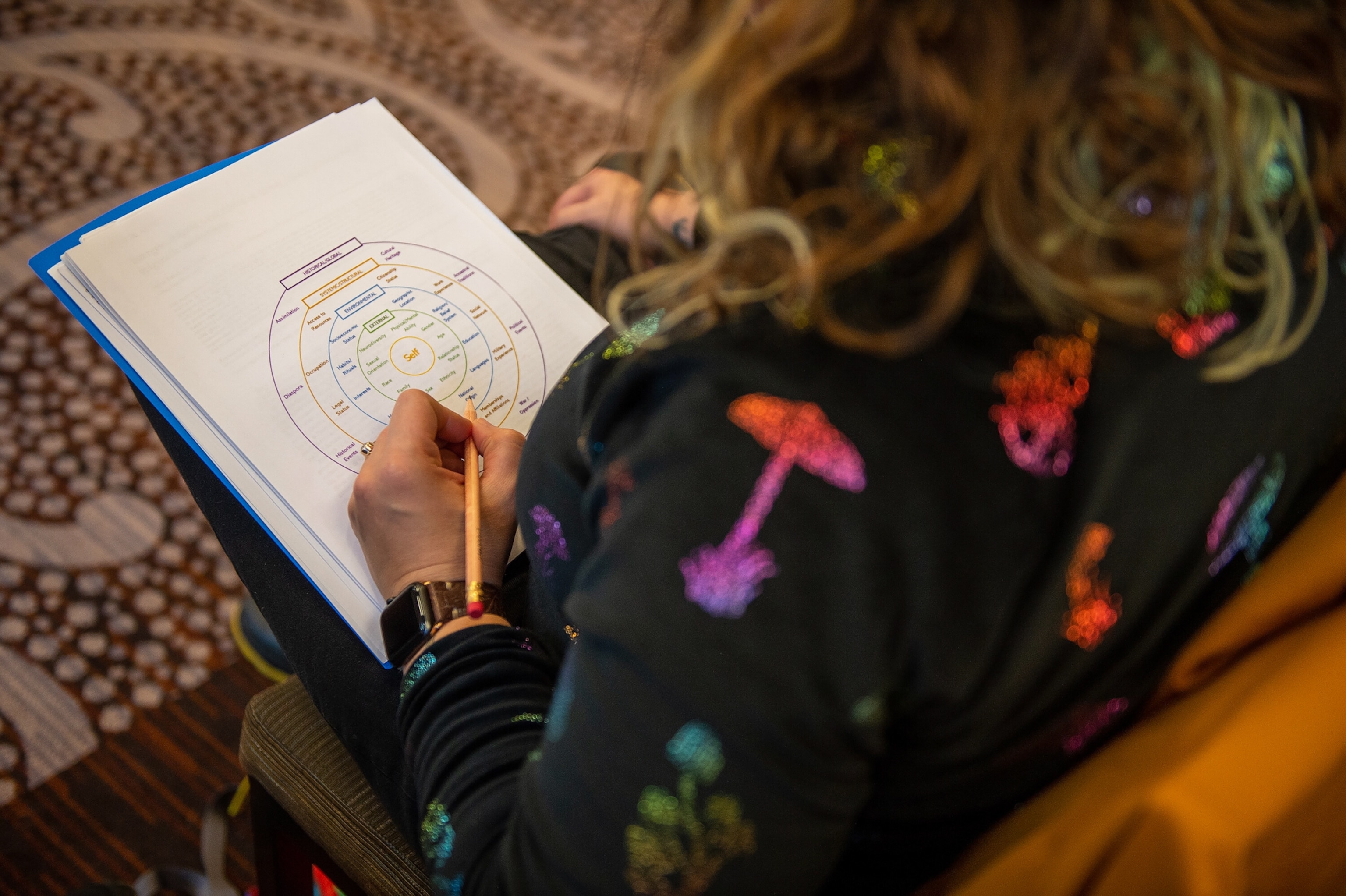

Most of the research on psychedelics in palliative care has focused on people with cancer. Typically, patients undergo physical and psychological evaluations in the weeks before the drug is administered and have several psychotherapy “integration” sessions afterwards. Often just one psilocybin session can produce ongoing mental health benefits.

In one Sunstone study published in 2023, half of the 30 participants with advanced cancer saw their depression go into remission within two months. When surviving patients were reassessed two years later, most remained in this improved state, Agrawal reported last summer.

Earlier psylocibin work showed impactful results in other aspects of mental health, too. A 2011 study at the University of California, Los Angeles, found anxiety plummet in a dozen advanced-cancer patients. In 2016, psilocybin improved mood and anxiety in 80 percent of the 51 cancer patients treated at Johns Hopkins University, while more than 60 percent of those treated at New York University (NYU) felt less hopeless six months after receiving the drug.

“This is a paradigm shift,” says Anthony Bossis, a clinical psychologist at NYU who co-led the 2016 research. Rather than solely providing symptomatic relief with an antidepressant, offering a psychedelic “enables the person to potentially explore their cancer, their life, the things that are existential and meaningful, which often resolves the suffering” at its deepest level, Bossis says. This may be why 70 percent of the NYU participants rated their psychedelic journey as among the most meaningful experiences in their life.

Psilocybin also reduces the demoralization many people undergo when diagnosed with a serious disease, even if they don’t have clinical depression, Bossis says.

Benefits for non-terminal cancer patients, too

Outside of clinical trials, U.S. law allows terminal patients to use a drug that is promising but experimental, on the theory they have little to lose. But psychedelic medicines are an exception. Palliative care physicians are unable to prescribe them for their patients because the compounds are classified the most restrictive category for illegal drugs, known as schedule 1. However, last summer, the Drug Enforcement Agency requested that U.S. Health and Human Services conduct a scientific review of psilocybin, a prelude to a possible rescheduling.

Separately, several private companies are working towards receiving U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of the drug for various mental-health conditions, which could widen its availability for people with less lethal diagnoses.

Ellen Labgold, a Leesburg, Virginia, psychotherapist who was diagnosed with stage 1 invasive breast cancer in 2022, knows the power of the drug for people in her situation. Her cancer retreated after a double mastectomy and medication, but knowing it could return, the mental scars remained.

Constantly anxious and depressed, “I’d wake up thinking about it, go to bed thinking about it, and wake up in the middle of the night thinking about it,” Labgold says of her cancer. She lost the desire to socialize and to host her annual pre-Christmas holiday bash. Every time she gazed at her baby granddaughter, joy mixed with sadness, as she worried she might not live to watch the girl grow.

In November, Labgold participated in a psilocybin clinical trial at Sunstone for people with various stages of cancer. While under the drug’s effects she felt like she was experiencing the universe as an interconnected whole, visualized by interlocking bands of jewel-colored energy. “It was really profound,” she recalls. “I felt connected to everything. Even the stuff that we see as ‘bad’ was still beautiful.”

(Psychedelics may help treat PTSD—and the VA is intrigued.)

From the moment the session ended, the negative thought patterns that had plagued her for years were gone, “It was a complete reset to my brain,” she says. She no longer fears her cancer’s return. This year she hosted her holiday party and feels optimistic about the future.

The future of cancer treatment

Not everyone improves after taking psylocibin, however, and those that do can intermittently backslide, more than a dozen global researchers including Bossis cautioned in an article in the Journal of Palliative Medicine. In fact, when eight participants in one of Canada’s programs were asked about their experience, most reported gains in depression, relationship issues, and spiritual well-being, but one said the drug had worsened each of these aspects.

For patients to benefit, the drug must be administered by someone properly trained in psychedelic medicine and delivered in a thoughtful setting that makes participants feel secure, Agrawal says.

(Psychedelic medicine is coming—but who’s going to guide your trip?)

During a session, the drug can cause headaches and nausea, as well as raise heart rate and blood pressure. For these reasons, as well as its hallucinogenic effects, some terminal people should generally avoid psychedelic medicine, including those with heart disease or psychosis.

But Labgold’s transformational experience highlights the limitations of current care for cancer, including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Agrawal likens them to treating the tip of the iceberg. The process downplays the psychological and spiritual support people diagnosed with this or other life-threatening diseases equally need.

“We need much better tools for advanced illness and end-of-life issues than we have now,” he says. Psychedelic drugs are “one of the most powerful I’ve ever seen.”