LSD for anxiety and depression? Some early studies show promise.

Researchers are investigating whether the drug could be used in mainstream medicine—with and without its hallucinatory effects.

In 1943, biochemist Albert Hoffman accidentally ingested a chemical that he had synthesized from a fungus and discovered that it created hallucinations. The mind-bending chemical was lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and psychiatrists seized on its possibilities. Within a decade, research determined the psychedelic to be safe, nonaddictive, and potentially valuable for treating trauma, substance use disorder, and other conditions. Some midcentury psychiatrists even conducted clinical sessions with patients under the influence.

But by the late 1960s, LSD lost its luster. It became the poster child for counterculture excesses, and laws restricted its access. Now, more than 50 years after it was banned, with growing acceptance of all psychedelic medicines and early research again showing the substance’s potential, LSD is roaring back.

In two important, if small, studies this fall, one or two sessions of LSD quelled symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder and major depression, results that lasted for months. Other researchers are evaluating the chemical for schizophrenia, end-of-life pain, cluster headaches, and other diseases.

LSD offers “exciting” possibilities, says Maurizio Fava, chair of psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital and a coauthor of the anxiety study, which used a proprietary form of the drug called MM120. “The standard medications that we use for depression or anxiety have either modest effects … or unwanted side effects, and you have to take them every day,” he says, while this compound seems “more efficacious and long lasting.”

Despite the recent flurry, LSD research lags other psychedelic medicines, especially methylenedioxy-methamphetamine, or MDMA, which was considered—and rejected—by the Food and Drug Administration in 2024, and psilocybin, a compound legally available in several states.

Some practical limitations make LSD harder to study. Trips are longer compared to other compounds, leading to higher costs for hiring therapists to supervise, and there are few pharmaceutical-grade manufacturers of the classic form of the drug.

But a key reason is its stigma, says David Olson, director of the Institute for Psychedelics and Neurotherapeutics at the University of California, Davis. LSD has a “branding issue,” he says. Because of its deep association with the counterculture, “people have a lot of misinformation about LSD.”

What does LSD do in the brain?

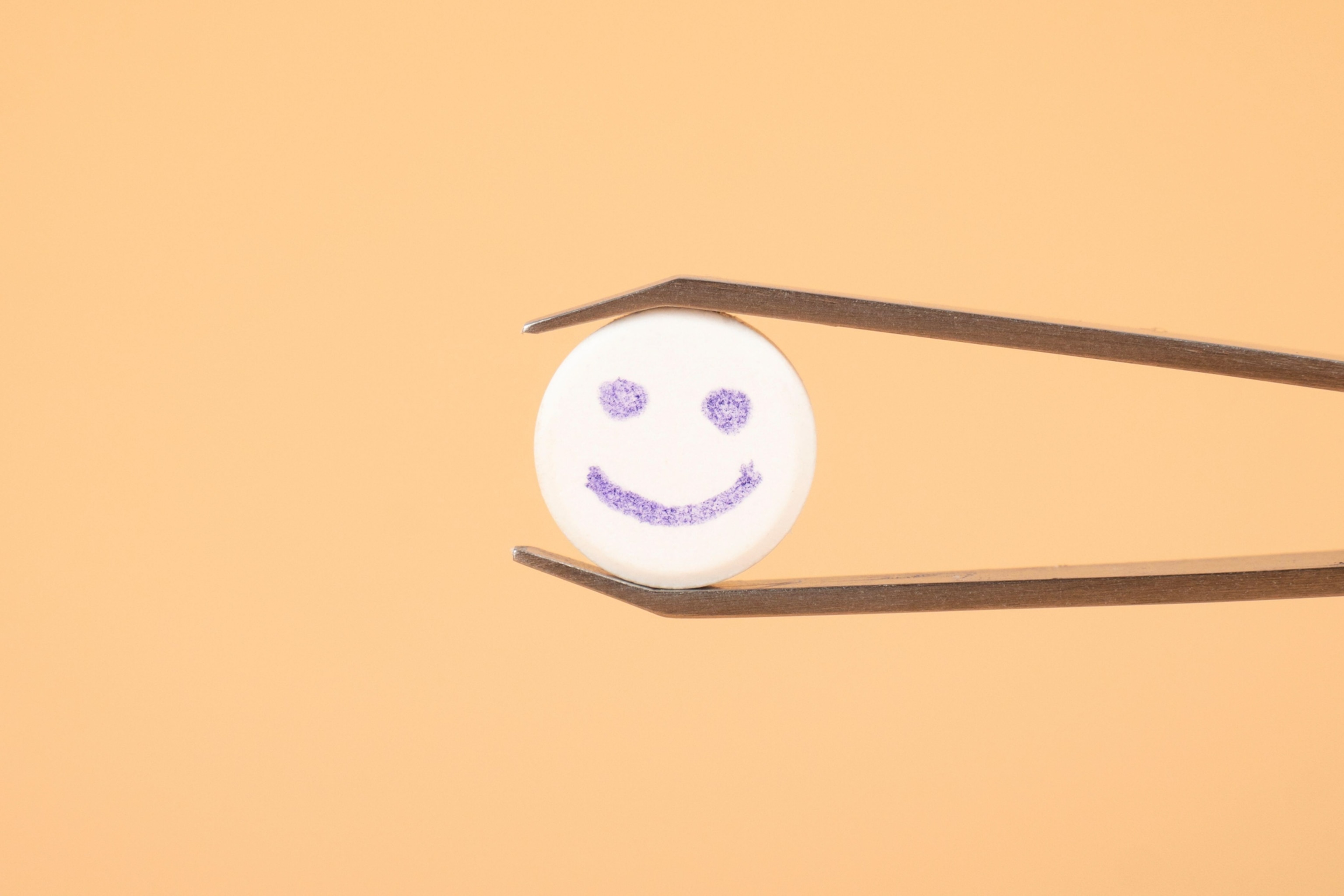

Researchers generally administer LSD in capsules, tablets, or oral solutions. (Ingesting the drug from decorated blotter paper is generally limited to illicit uses.) Once absorbed, the drug causes extensive visual hallucinations, powerful distortions in the sense of time and personal identity, and impaired perception of objects and sounds. One defining characteristic is sensory crossover, known as synesthesia, such as hearing the color purple or seeing musical sounds.

Like other psychedelics, the drug may produce a “good trip” with positive sensations and personal insights, or a “bad trip” of panic, fear, and despair—sometimes both in a single session. Common side effects include nausea and headaches.

LSD affects the serotonin system, intricately involved in mood and mental health. It also stimulates growth in brain neurons, especially the parts that enhance memory and learning.

But the question of “what exactly happens in the brain when people are having these extraordinary experiences under LSD is a huge mystery … and we are very, very far from having an answer,” says Kenneth Shinozuka, a psychiatry researcher at Stanford University.

Still, researchers are taking small steps toward solving the mystery. An imaging study published this summer found that brain regions become less coordinated with one another and activity in each becomes less predictable, though the results have yet to be reviewed by other scientists.

Shinozuka’s own recent work, published in April, reveals that a section in the front of the brain, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, wakes up during a trip. That area is implicated in depression, which is why it is stimulated with magnetic pulses to treat severe cases of the disease, he says. The thalamus, a gatekeeper that selects which sensory inputs to send to the rest of the organ, is also altered, “supporting the hypothesis that psychedelics open the doors of perception” a famous phrase of the late author Aldous Huxley, says Clayton Coleman, another of the study’s researchers.

Anxiety seems especially ripe for LSD

Whatever their mechanisms, it’s becoming evident that the substance yields mental health improvements, especially for anxiety. In a small study published in Biological Psychiatry a few years ago, anxiety fell substantially in the months after two sessions with 200-micrograms of classic LSD.

The latest MM120 study looked at multiple dosage levels. Some 200 people with generalized anxiety disorder received one of four dosages, 25, 50, 100, or 200 micrograms, or a placebo. Almost half of those getting the two higher doses were in remission by the three-month follow-up, while the two lower ones fared no better than the placebo. Larger studies are currently underway to further test the medicine for anxiety and for depression with results expected in 2026, according to MindMed, the drug’s developer.

The approach of using different doses helped to alleviate a common criticism of psychedelic medicine studies—that people can easily deduce whether they got the drug or the placebo and potentially skew the results, Fava says. Because people in all four groups experienced some measure of hallucinations, this reduced their ability to successfully guess, leading to more accurate “blinding,” a hallmark of quality research.

(Will psychedelics ever live up to their hype?)

Can LSD work without the trip?

Not all of the current LSD research involves a journey to outer space. Some scientists are exploring very low doses, known as microdosing; others are examining a version specially designed to remove the psychedelic experience but still deliver the brain benefits.

Harriet de Wit, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, began studying LSD microdosing after reading reports from thousands of people online who claim their (illegal) intakes boost their mental health and productivity. But when she gave 56 healthy people 13 or 26 micrograms or a placebo four times over several weeks, mood and performance did not improve. New Zealand scientists employing 10 microgram doses had similar results.

Despite the negative findings, De Wit’s lab has several ongoing microdosing studies, including one evaluating depression. “With so many people saying microdosing changed their lives,” research may yet uncover its potential, she says, perhaps by giving the drug for longer or targeting specific groups of patients that may be more likely to benefit.

(Can microdosing psychedelics boost mental health?)

Transposing two atoms in LSD can remove its psychedelic effects entirely. UC Davis’s Olson is experimenting with this analog, called JRT, in high doses. In laboratory tests, the molecule encouraged neurons to grow and change, or increase plasticity, and in mice, it improved depressive behavior.

Such a medicine could be a game-changer for people with conditions characterized by a loss of tissue in the brain’s cortex for whom hallucinations could be harmful, says Olson, a cofounder of Delix Therapeutics, which is developing the drug. Schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, and traumatic brain injury all fall into this category. It might also benefit those who don’t want to take a full day off work for a psychedelic medicine experience. Studies in humans are expected to begin in the next few years.

(Why scientists want to create psychedelics that give better trips.)

Some question whether the mind-altering experience is expendable or is instead a crucial part of the healing. In the Biological Psychiatry study, people having mystical-type experiences during their trip were more likely to reduce their anxiety. In a recent editorial in JAMA discussing MM120, experts note it remains unclear whether the benefits “were related to … the intensity of perceptual changes or experiences during the dosing sessions.”

Whatever forms ultimately prove most therapeutic, “LSD is a compound with enormous therapy potential,” Olson says. That’s the vision he hopes people will eventually conjure, instead of hippies turned on and tuned in, when they hear the letters LSD.