How strep throat may trigger autoimmune disease

Growing research suggests the bacteria left behind by the common childhood infection may trick the immune system into attacking both the invader and the body's own cells.

For most people, strep throat is a temporary infection that can be cleared with a short course of antibiotics—something an estimated 5.2 million people in the United States are treated for each year.

But in a handful of cases—as many as 1 in 200 children diagnosed with certain post-streptococcal autoimmune conditions—the story does not end when the painful swallowing subsides. Instead, the infection can leave a lasting imprint on the immune system—one that, under some circumstances, may trigger autoimmune disease and other long-term complications.

“Your immune system is designed to protect you from infections,” says Ilan Shapiro, medical director of health education and wellness and a physician at AltaMed Health Services. “But sometimes that system becomes confused and starts attacking healthy tissue instead, which is when autoimmune disease develops.”

A growing body of recent research examining how infections can disrupt immune signaling and even wreak havoc on the brain is sharpening scientists’ understanding of how that confusion begins—and the role strep throat may play. In some individuals, the bacteria that cause strep don’t just irritate the throat, they can set off immune reactions that spread throughout the body, affecting the heart, joints, blood vessels, and even the brain.

Some researchers are even exploring whether longer-lasting immune changes after infection could contribute to illnesses such as chronic fatigue syndrome, a condition marked by extreme fatigue lasting at least six months.

What is emerging is not a story of inevitability or alarm, but of biological nuance—as scientists work to understand how a familiar childhood illness can intersect with the immune system in ways that can lead to long-lasting effects.

How strep triggers the immune system

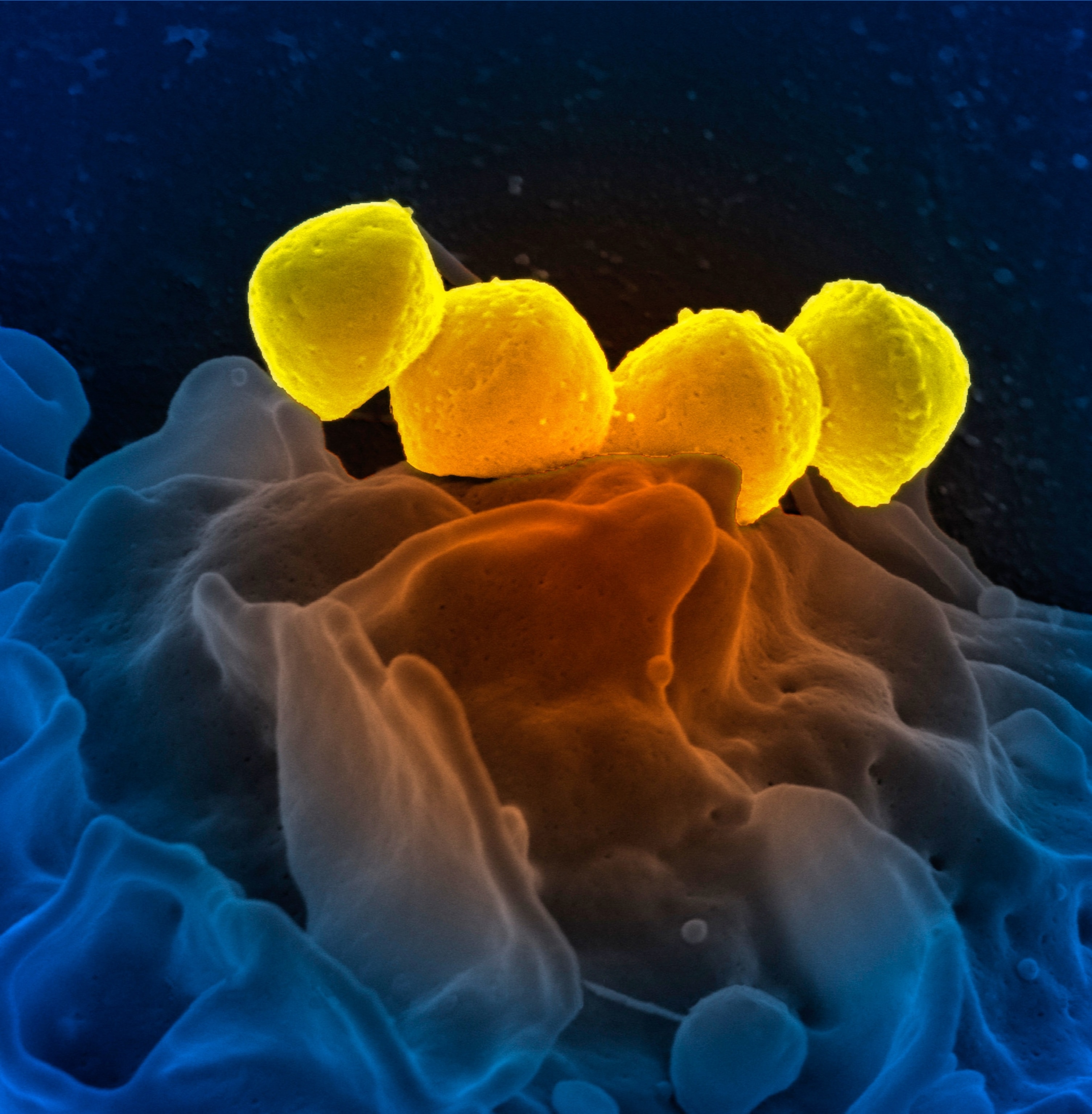

Strep throat is one of the most common bacterial infections in the world, affecting some 600 million people globally each year. It’s caused by Group A Streptococcus, a bacterium that spreads through close contact with an infected person.

“Swallowing can also be painful, and the lymph nodes in the neck may become swollen and tender as well,” says Jason Nagata, a pediatrician at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. And unlike viral sore throats, he adds, strep throat typically does not cause a cough or runny nose.

(What your mouth can reveal about your health.)

For most people, time or antibiotics clear the infection completely. But strep is unusual among infections because it has long been linked to delayed complications that can appear weeks or even months after the sore throat resolves. These complications can affect multiple systems, including the heart, joints, skin, blood vessels, and nervous system.

Links between strep infection and autoimmune complications date back to the late 1800s in the case of scarlet fever or rheumatic fever; and PANDAS—often characterized by the sudden onset of obsessive-compulsive behaviors, tics, or both—was first described in the early 1990s. Yet scientists are still investigating why strep is such a well-established trigger for such a wide and still-expanding list of autoimmune conditions.

In fact, an estimated 8 percent of the U.S. population lives with one of the 80 to 150 recognized autoimmune diseases—many of them experiencing chronic pain, fatigue, lifelong medication needs, and unpredictable flares that are very hard to plan around. “The patients who I have with these conditions struggle to go to school, pursue their usual extracurricular activities, and spend time with friends and family,” says Scott Hadland, a physician and chief of adolescent and young adult medicine at Mass General Brigham for Children.

Autoimmune disease develops when the immune system loses its ability to reliably distinguish between foreign invaders and the body’s own tissues. While researchers do not yet fully understand why this happens, Nagata says most evidence points to a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers.

In the case of strep, one mechanism stands out to researchers: molecular mimicry. This occurs when components of a pathogen closely resemble the body's own proteins, tricking the immune system into attacking both the invader and the body’s own cells.

“Molecular mimicry happens when the immune system makes antibodies to fight the strep bacteria (but) those antibodies don’t just recognize the bacteria—they also recognize similar-looking proteins in the body,” causing them harm, explains Hadland. This phenomenon appears particularly relevant in strep infections because certain streptococcal proteins share structural similarities with human tissues.

Another mechanism sometimes at play is an unusually large, non-specific immune response. In such cases, the Group A Streptococcus bacterium “releases a ‘super’ antigen, which causes such a large and broad inflammatory response that it attacks your own tissue as well as the bacteria,” explains Cassandra Calabrese, a rheumatologist and infectious disease specialist at Cleveland Clinic. In other words, instead of precisely targeting the infection, the immune system launches an all-out alarm—one that can end up damaging healthy tissue in the process.

Researchers are also uncovering how post-streptococcal immune reactions may also affect the brain as studies show that immune cells activated by a strep infection may travel along the nerves connecting the nose to the brain, and “can actually break down the blood-brain barrier,” Calabrese explains.

When that protective barrier weakens, immune cells and antibodies can also enter brain tissue, where they don’t normally belong. This can amplify inflammation in the central nervous system and may help explain why some children suddenly develop neurological symptoms, such as those seen in PANDAS, following a strep infection.

Could post-strep immune changes spill into chronic fatigue syndrome?

While Calabrese says there is strong evidence linking strep infection to many autoimmune disorders, “the evidence behind the cause of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is still under investigation and remains more uncertain than these other disease processes.”

One reason is that CFS—a condition marked by profound exhaustion lasting longer than six months that does not improve with rest—is not considered a classic autoimmune disease.

Instead, it is increasingly understood to be a complex disorder involving immune dysfunction, chronic inflammation, impaired energy metabolism, and abnormal responses to exertion.

That said, researchers increasingly believe CFS likely involves abnormal immune responses to infection or stress; “and some people do report CFS symptom onset after a strep infection,” says Nagata.

Several recent studies have strengthened this post-infectious framing. For example, a study published in 2025 found that people with CFS show exaggerated innate immune responses to microbial signals, suggesting the immune system remains stuck in a heightened defensive state long after an infection has resolved.

Other work has documented persistent inflammatory signaling and impaired immune regulation in patients following viral or bacterial illness.

But what remains unclear is the specific role the bacteria responsible for strep may be playing. “While it has been hypothesized that an acute bacterial infection can lead to more chronic immune changes,” says Zara Patel, a professor of otolaryngology and the director of endoscopic skull base surgery at Stanford Medicine, “at this point, most of the data are correlational, and we do not yet have high-quality evidence demonstrating direct causation.”

It is also unclear whether strep acts independently or as “one of several triggers,” says Shapiro.

How to reduce your risk for strep

While scientific understanding continues to evolve, clinicians agree that prompt diagnosis as soon as symptoms appear is critical. “This simple throat swab can be the crucial step in moving quickly forward with appropriate antibiotic treatment and prevention of the development of these post-infectious immune problems,” says Patel.

This is especially important, Shapiro notes, because the risk of long-term complications may be higher in people with repeated infections, delayed or incomplete treatment, and those with age-related vulnerabilities or a family history of autoimmune disease.

For those diagnosed with strep throat, “completing the full prescribed course of antibiotics is essential—even if symptoms improve quickly,” says Nagata.

To help prevent strep throat in the first place, “everyday hygiene goes a long way,” Nagata adds. This includes regular handwashing, avoiding shared drinks or utensils, and staying home when sick.

As research continues to connect everyday infections to long-term immune health, the takeaway is not fear, but perspective. “Serious long-term complications after strep are rare,” stresses Hadland. “Most people recover completely with appropriate treatment.”