11 Museum Surprises: Rediscovered Treasures, from a Celtic Brooch to an Early Hitchcock Film

These newly identified objects were mislabeled, misplaced, or simply mysterious.

A museum is like a theater for art and artifacts. In the front of the house, the pieces of the collection play their various roles for an attentive audience gathered in a hushed space.

But behind the scenes, the support staff works in controlled chaos, scrambling to put on the show. Inevitably, in the midst of the drama, curators lose track of things for a while—sometimes a very long while.

Take the case of a mysterious lump of organic material that the British Museum acquired in 1891, along with other objects from a Viking grave in Norway:

1. All That Glitters

The lump, perhaps the remains of a wooden box, sat in storage until recently, when a glint of something shiny caught a curator's eye.

An x-ray scan revealed a staggering discovery: The lump contained an ornate gilded Celtic brooch created in Ireland or Scotland in the eighth or ninth century. Vikings must have looted the ornament in a raid and taken it home, where it was buried with one of their high-status women.

Now cleaned and curated, the brooch was scheduled to be put on display on March 27, at long last.

But its saga isn't unique. Museums are filled with surprises waiting to be rediscovered—things that were mislabeled, misfiled, miscataloged, misidentified, unidentified, or, like the British Museum's brooch, stored and ignored.

Here are ten other tales of historic objects that were hiding in plain sight:

2. Geographically Challenged

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark collected a Native American bear claw necklace during their 1804-06 expedition across what is now the western U.S. The artifact was first cataloged in 1889 at the Peale Museum in Philadelphia.

After changing hands a couple of times, it ended up at Harvard University's Peabody Museum, where someone mislabeled it. Two collections assistants found it during an inventory in December 2003 among artifacts from the South Pacific Islands.

3. Ice Age Silhouette

In the 1830s or '40s a village priest in France found a 14,000-year-old reindeer antler engraved with the image of a horse. Likely the first piece of prehistoric art ever discovered, the antler was acquired by the British Museum in 1848 and then transferred to London's Natural History Museum when that institution was created in 1881.

There it was briefly displayed, put in storage, rediscovered in 1989—and promptly forgotten again for more than a decade. Finally, in 2013, a team of experts gave the antler its due, conducting a proper study and publishing a paper about it in the journal Antiquity.

4. Dial H for Hitchcock

In 1989 the New Zealand Film Archive acquired a collection of old movies from the U.S. More than 20 years later an American film expert came to check them out—and discovered the first half hour of The White Shadow, a long-lost silent film from 1923 that Alfred Hitchcock worked on early in his career, before becoming a famous Hollywood director.

The first two reels bore the label "Twin Sisters," and the third was listed as an "Unidentified American Film." Whether the last three reels of the movie have survived somewhere is unknown.

5. Fossil Flub

The remains of an extinct marine reptile came to light on a Kansas ranch in 1950. They were identified at the time as belonging to a creature called Brachauchenius lucasi—a misidentification, it turns out.

The Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays, Kansas, put the fossil on display, with the skull embedded in plaster so it appeared as if it were still encased in stone. And there the fossil remained for more than half a century, described as one of the best specimens of its kind.

Last year a paleontologist from another museum decided that the ID seemed fishy and convinced the Sternberg to investigate.

After the plaster was removed from the skull, experts realized that the fossil belonged to a previously unknown ocean predator that lived 91 million years ago. Based on its giant head studded with dagger-sharp teeth, they gave it the name Megacephalosaurus eulerti. The first word means big-headed reptile. The second is a nod to Otto Eulert, the man who owned the land where the fossil was found.

6. Masterpiece Unveiled

A notorious 16th-century Italian's portrait was acquired by the National Gallery in London in 1924. His name? Girolamo Fracastoro. His claim to fame? A word for the sexually transmitted disease that was terrifying his countrymen—syphilis—was derived from a poem he wrote.

The portrait was damaged, darkened by varnish, and unsigned, so the museum staff relegated it to a basement gallery despite Fracastoro's renown.

Eventually, cleaning and conservation revealed the hand of a master artist. After close examination, curators decided last year that the artist must be the famed Venetian painter known as Titian. The portrait now hangs in one of the museum's main galleries.

7. Famous Words

The audio recording of a long-lost speech by Martin Luther King, Jr., came to light last year at the New York State Museum in Albany.

King gave the speech on September 12, 1965, one year before his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. Lasting about 26 minutes, it was recorded on a reel-to-reel magnetic tape.

In November 2013, during the museum's 10-year project to digitize the thousands of audio and video tapes in its collection, a college intern spotted an intriguing label on a box. It read "EP Dinner NYC" and "Rockefeller, Martin Luther King, Sept. 12, '62."

The intern removed the reel that was inside the box, placed it on a tape machine, and hit the play button.

In one electrifying moment, King's voice came to life once again. He was speaking to the New York State Civil War Centennial Commission, convened by New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, to celebrate the centennial of a document known as the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

"We've exhibited the typewritten text of the speech before," said a state official quoted in a January 2014 press release, "but this audio recording allows us to experience the real power and courage of Dr. King's speech as he delivered it back in 1962."

Click here to listen to the speech and learn about its historic context, including the efforts made by King and others to bring racial equality to the U.S. more than a century after President Abraham Lincoln freed the country's slaves.

8. Odd Object

The 2010 excavation of a trash heap from about 1810 near New York's City Hall turned up a puzzling three-inch-long (7.6-centimeter-long) cylinder of animal bone. "We thought it might be a pin case or some sort of spice grinder," said archaeologist Lisa Geiger in an email, "but we weren't confident in either of those ideas."

The mysterious cylinder was sent to storage at Brooklyn College along with the ceramics, glassware, and butchered bones that were also found at the site.

When Geiger later volunteered briefly at Philadelphia's Mütter Museum—home to all manner of historic medical curiosities—she came across a clue that helped her solve the puzzle of the cylinder. It was a similar-looking object from the mid-19th century, identified as a metal vaginal syringe.

"Once I had that to go on, I started to realize there were many of these syringes recovered from 19th-century sites, usually made of metal, glass, or early Bakelite plastic," she says. "My research revealed how many women began adopting vaginal syringes for douching as a hygienic practice and as a contraceptive. Ads for syringes used a lot of coded language suggesting they were for 'married women'—approved sexually active women—and could be used with a variety of astringent tinctures."

Now that the cylinder's place in history has been established, Geiger hopes a museum will find a place for it in the future.

9. Pharaoh's Adviser

Sometime between 1894 and 1907, excavations at the ancient Egyptian site of Deir el-Bahri uncovered a badly damaged fragment of a limestone statue. Measuring 19 inches (48.5 centimeters) tall and 12 inches (31 centimeters) wide, it was shipped to the Manchester Museum in the U.K., where it was cataloged as a Middle Kingdom (ca 1975-1640 B.C.) piece based on the hieroglyphs it bore.

A recent re-reading of the hieroglyphs revealed an intriguing title: Priest of Amun-Userhat. Only one person is known to have held that position, a man named Senenmut. As a close adviser of Queen Hatshepsut, he was one of the most powerful nonroyal people of the New Kingdom (ca 1539-1075 B.C.).

The museum summed up the discovery by saying: "It just goes to show what treasures lie undiscovered in our storerooms."

10. Christian History

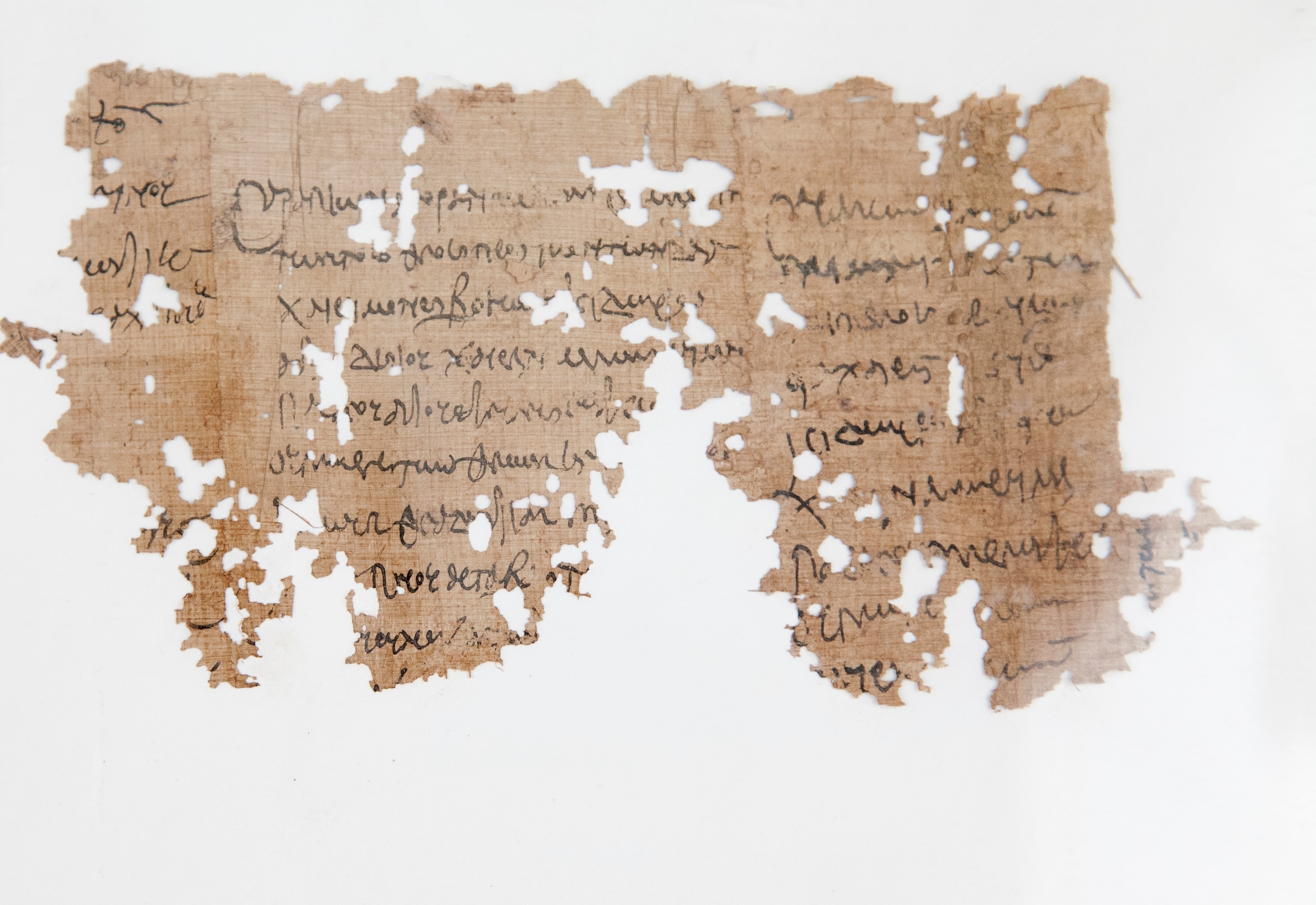

A cardboard box sitting in a storeroom for decades at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, held a stack of ancient treasures—nine papyrus documents from ancient Egypt. In January a sophomore uncovered them as she was going through the papers of a deceased professor.

All were written in ancient Greek and date from the first to the fifth centuries A.D. Most deal with accounting, but one was quite rare. Known as a libellus, it dates to the year 250, when Emperor Decius launched Rome's first great persecution of Christians. According to his decree, all loyal subjects of the empire were ordered to make a sacrifice to the gods.

A libellus confirmed in writing that a Roman citizen had complied with the decree. Christians were forbidden by their beliefs to make such sacrifices, so they'd never receive a libellus unless they procured it illegally. Without one, they were subject to arrest and even execution.

The professor who owned the papyri taught classics at the college for many years. He probably collected the documents when he worked on an archaeological excavation in Egypt in 1924-25.

As soon as preservation work is completed, the college plans to display the papyri in its library. It also hopes to put digital copies online for scholars around the world to study.

11. Wrong Folder

An important document from the time of the U.S. Revolutionary War almost ended up in the trash at New York City's Morris-Jumel Mansion. Constructed as a British colonel's summer house in 1765, the building became General George Washington's headquarters in the fall of 1776. It has been a museum since 1904.

The 12-page document is a final plea for reconciliation addressed to the people of Britain in 1775. The handwritten draft was penned by Robert R. Livingston, a prominent New York attorney, at the behest of the Continental Congress.

It was likely donated to the museum in the early 1900s and was somehow misfiled in a folder of doctor's bills from the colonial period. Deemed not worth keeping in the 1970s, the folder was supposed to be thrown out. Instead, it ended up in a desk drawer in the museum's attic. That's where an intern discovered it last year.

The museum decided to sell the letter, which brought $912,500 at auction this past January. Part of the windfall will pay for improvements to the mansion, and the rest will fund an endowment for future needs.

The original letter has not survived. By the time it got to London, King George III had already set the wheels of conflict in motion.

Follow A. R. Williams on Twitter.