King Tut: The Teen Whose Death Rocked Egypt

Famous for his tomb full of golden treasures, the boy pharaoh was a pivotal figure in shaping the future of Egypt.

Nearly a century after the discovery of King Tut’s tomb, archaeologists are once again crowding into the crypt of the boy pharaoh.

Recent scans of the tomb reveal that it might have yet another secret within its walls—hidden chambers, including one which might have been the final resting place for Queen Nefertiti.

Why would two of ancient Egypt's most famous rulers share the same tomb? The answer might lie in the story of Tut’s life and death. His premature demise in about 1322 B.C. likely shocked his subjects—and left them deeply apprehensive about their future.

The young pharaoh ruled at the end of the 18th Dynasty, at a time when Egypt had become fabulously rich and powerful. The country had prospered for more than a thousand years, keeping traditions that had arisen even before the now famous pyramids at Giza were built. By Tut's time, Egypt had gained access to the legendary gold mines of Nubia to the south, and had conquered territory along the Mediterranean coast to the northeast.

But Egypt was in turmoil when Tut took the throne. A pharaoh named Akhenaten, possibly Tut's father or half brother, had turned traditions upside down by ordering everyone to worship the sun god Aten, closing the old temples, and smashing all the statues of Amun, a popular god with powerful priests.

The heretic pharaoh also moved the country's capital to the western desert, far from the life-giving waters of the Nile. He called the place Akhetaten, now the archaeological site of Amarna, and forced more than 20,000 people to do the backbreaking work of building an entire city from scratch.

It's unclear who became pharaoh right after Akhenaten died, but Tut soon rose to the throne. His full name was Tutankhamun Nebkheperure, quite a mouthful for a small boy. Tut was only eight years old or so, which must have set his subjects to worrying all over again. A boy king? How could he rule a whole country? And how could he ever hope to protect Egypt from its enemies?

His top officials, though, appear to have offered him good advice and worked diligently to set Egypt right. For starters, that meant moving the capital back to the banks of the Nile, where the city of Luxor is now located. During his decade-long reign, Tut became a symbol of this restoration, a return to ma'at, the proper order of things.

Photo Gallery: King Tut’s Fabulous Treasures

Untimely Demise

And then, stunningly, the teenage pharaoh died. The cause is uncertain. Maybe a lethal infection set in after he broke his leg in an accident. Or malaria did him in. Or he had a fatal genetic weakness that arose from the royals' habit of marrying their siblings.

However it came about, Tut's passing created an immediate practical problem: There was no finished tomb to put him in. And why would there be? No one could have imagined that a teenager would suddenly drop dead. Egypt's officials must have thought they had plenty of time to prepare his place of eternal rest.

Many experts think Tut may have been buried in a tomb that had already been prepared for someone else. It's now known as KV62—uncovered in the Valley of the Kings, which was the cemetery for rulers and their relatives during the 18th and 19th Dynasties.

But what if KV62 was already occupied, and Tut was buried in a few small rooms near the entrance? That's what the current scans of the walls of Tut's burial chamber are meant to determine.

Maybe the first occupant is lying in larger rooms beyond Tut's modest suite. And if it's the beautiful queen Nefertiti, or a royal of the same stature, the rooms might be filled with great treasures, all untouched by looters.

Unfortunately, Tut died without a son and heir, plunging Egypt yet again into a period of anxiety that lasted about two decades, until a new dynasty was founded.

As the tombs of new pharaohs were carved into the limestone cliffs in the Valley of the Kings, chunks of rock must have piled up everywhere. In time, the debris spilled over the entrance to Tut's tomb. With no physical reminder of his whereabouts, the teenager was all but forgotten.

More than 3,000 years later, wealthy Europeans began to explore the various royal burial grounds of the ancient Egyptian capital, searching for stunning artifacts to fill their homes and museums. One of these was Lord Carnarvon, whose home was Highclere Castle. Television viewers today know it as the setting for the PBS show Downton Abbey.

Beginning in 1907, Carnarvon employed a fellow Brit, Howard Carter, to supervise the excavations he was funding. They had some success, finding upper class tombs and previously looted royal burials, but by the winter of 1921-22 they had yet to make the big score they had hoped for.

Carnarvon was ready to pull the plug, but Carter convinced him to hang in for one more season of digging. It was one of the best calls in the history of archaeology.

In November 1922 Carter's workmen began clearing a previously neglected triangle of ground in the Valley of the Kings. After just a few days, they hit the descending stone staircase that would lead them to Tut's underground grave.

By the end of the month, they had come to a doorway sealed with plaster that had the name of Tutankhamun stamped all over it. Carter broke a small hole through the plaster, held up a candle, and looked in. What he saw would make newspaper headlines around the world:

"At first, I could see nothing," he wrote later, "the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle to flicker, but presently, as my eyes became accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, gold—everywhere the glint of gold."

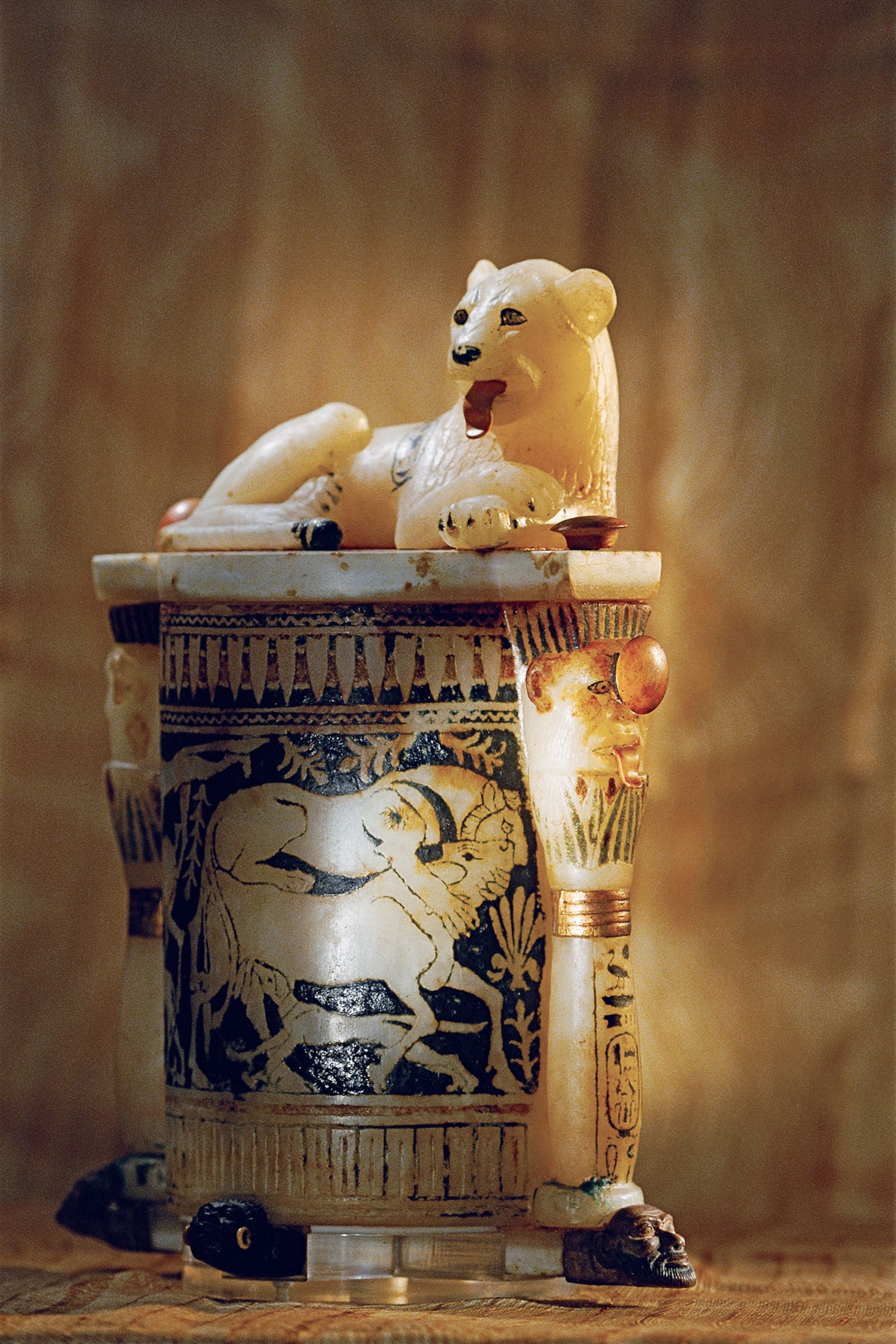

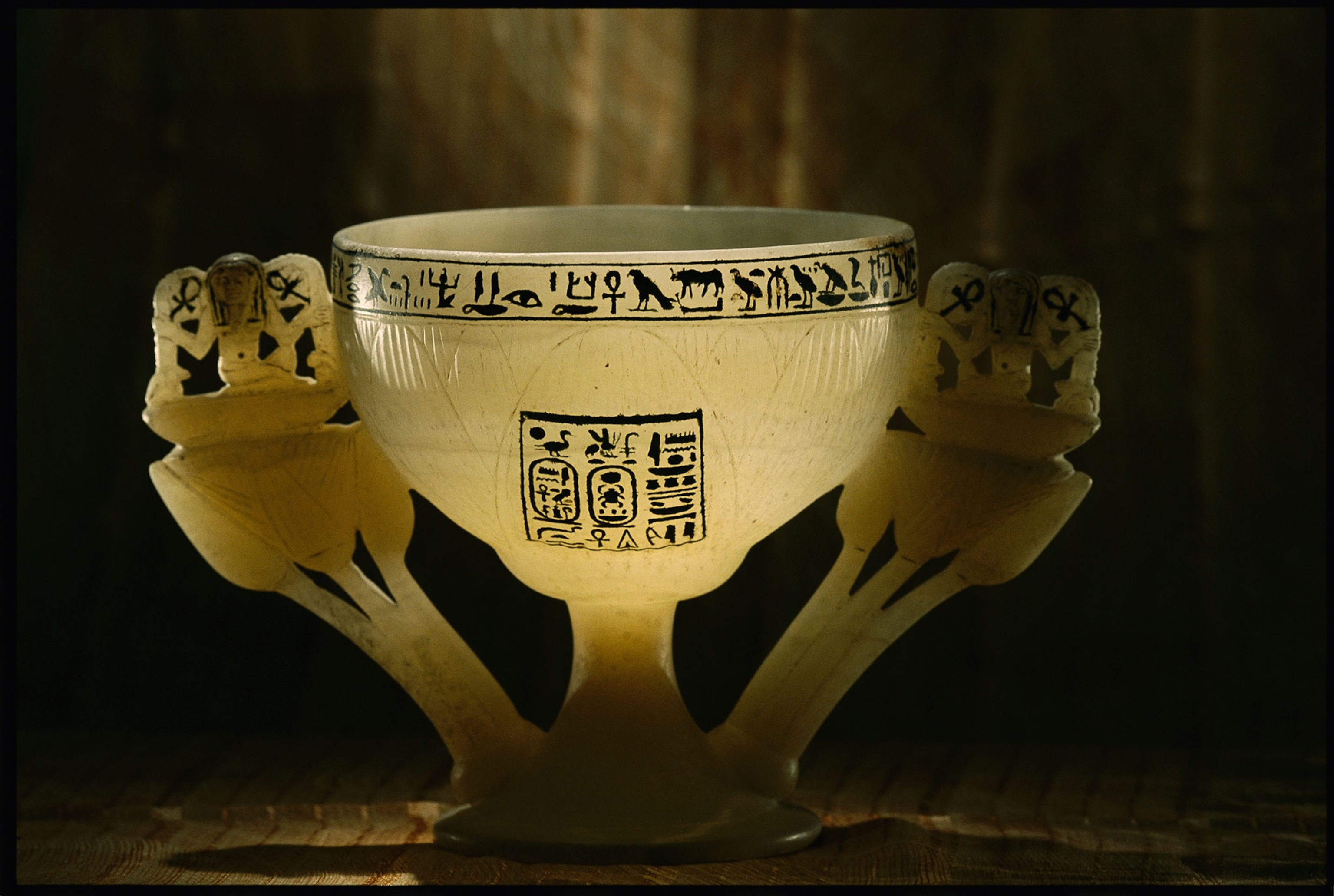

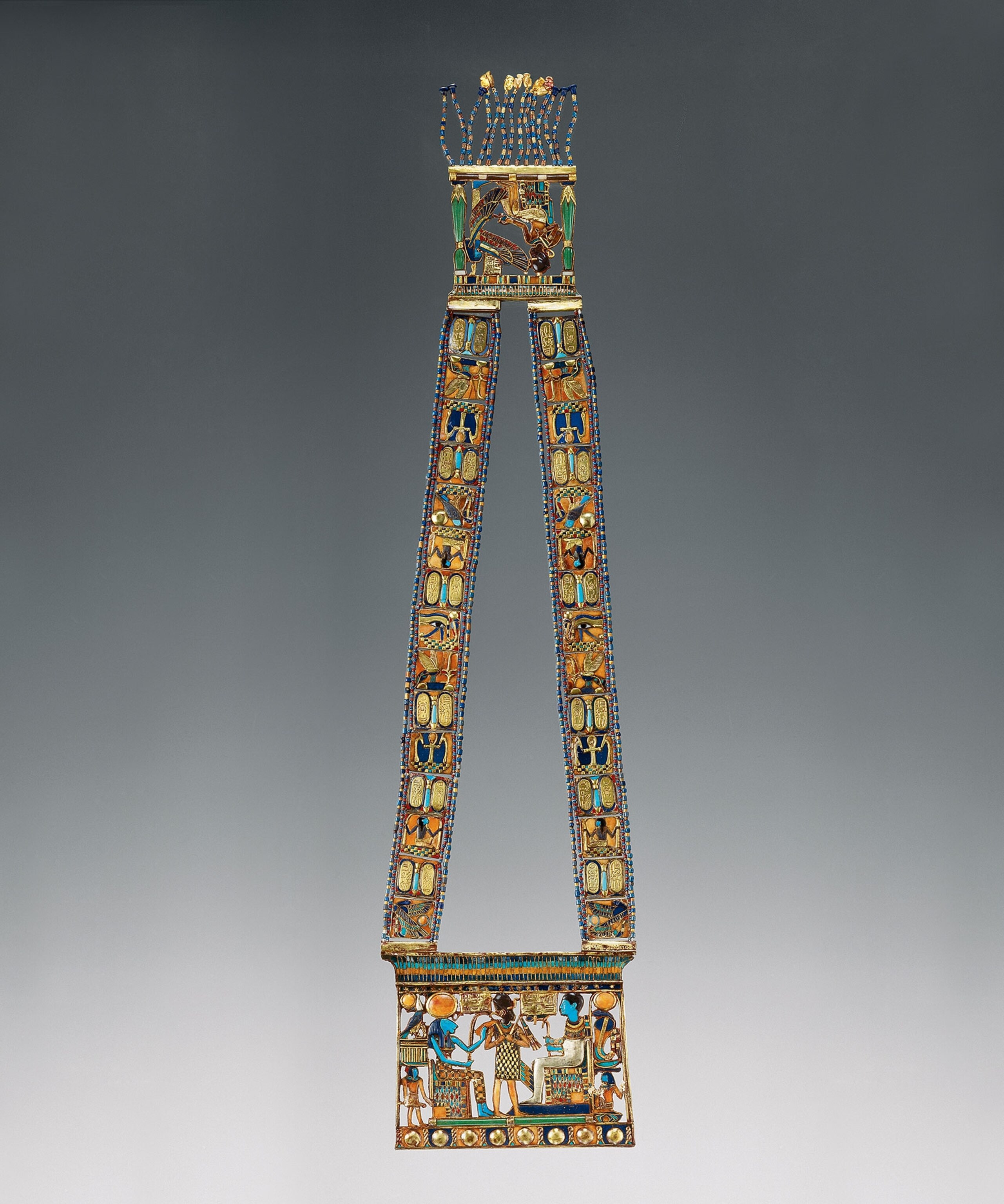

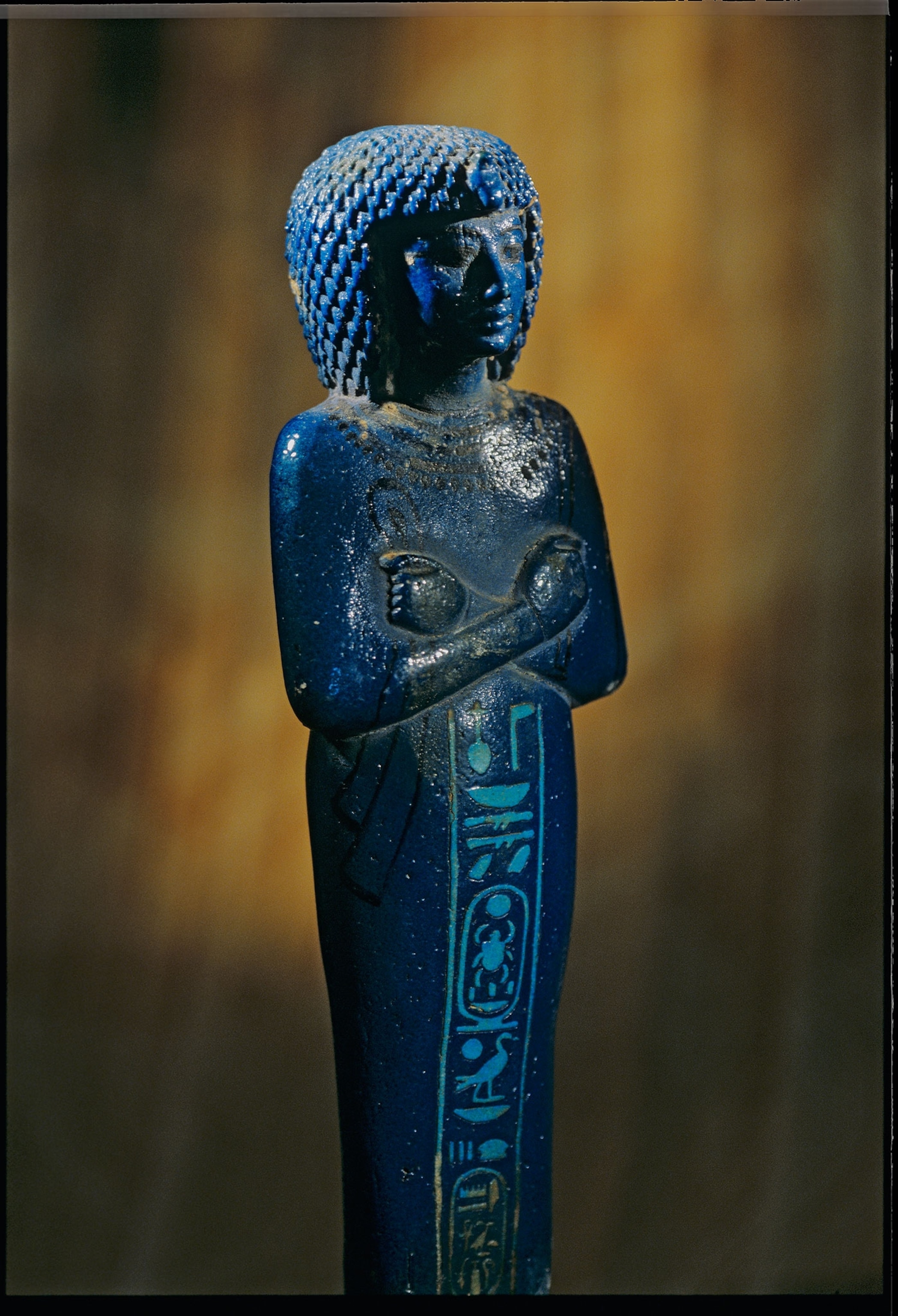

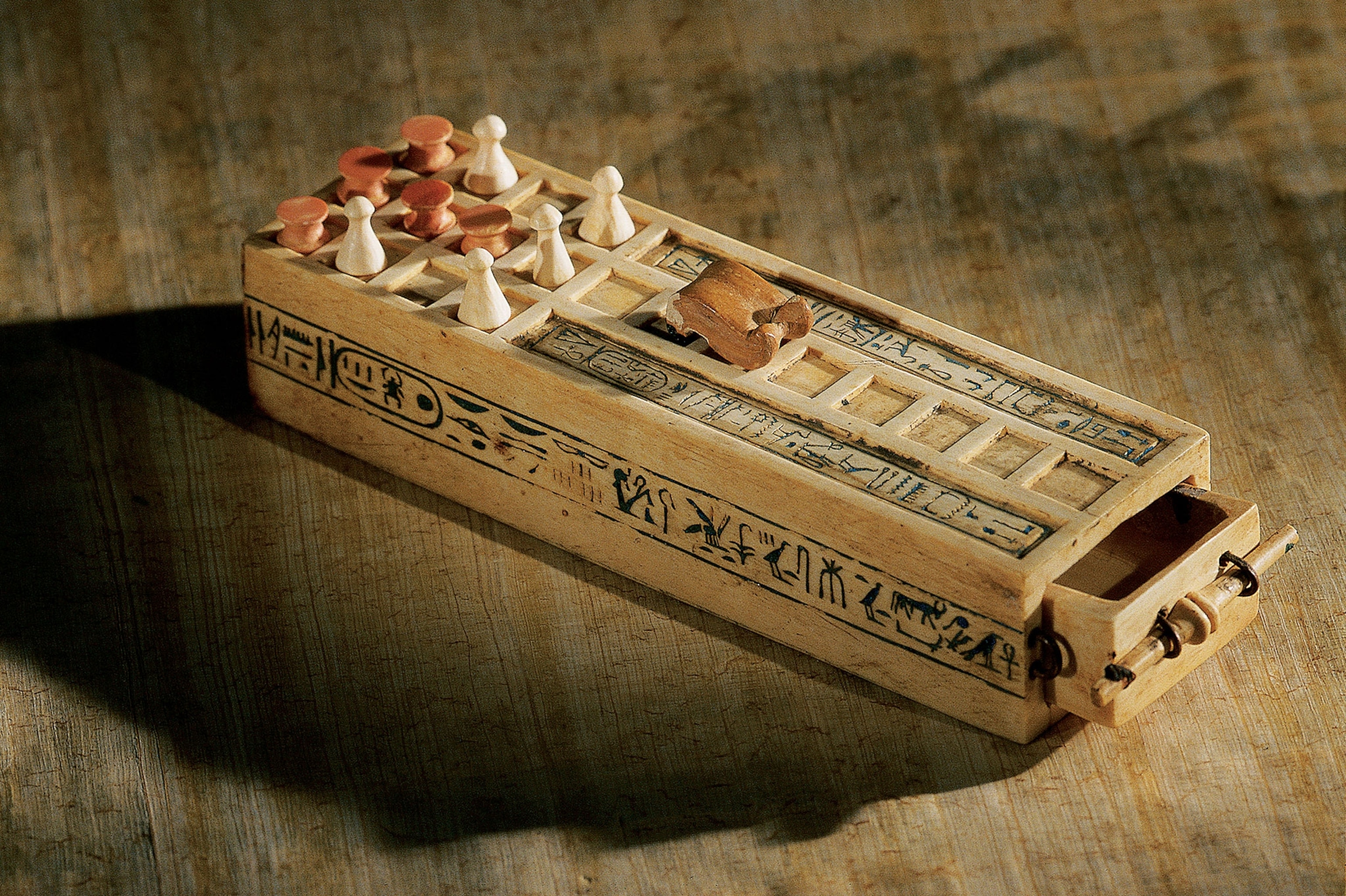

It would take Carter the next ten years to catalog all of Tut's treasures. The boy king had been provided with 5,398 things he might need in the next life—everything from a solid gold coffin and face mask to beds and thrones, chariots and archery bows, food and wine, sandals and fresh linen underwear.

Although looters had broken into the tomb at least twice in antiquity, it remains the most spectacular burial ever discovered in Egypt. And this was for a teenager with a relatively short reign. The mind boggles at the thought of the wealth that must have been buried with one of the big names—like Nefertiti.

Tut's reign may not have been filled with great military battles or political coups, but he was more than a minor blip on the list of kings. His death, without an heir, made him a pivotal figure in shaping the future of Egypt.

He and his wife, Ankhesenamun, tried to start a family but found only heartbreak. Their two daughters were delivered before term, both apparently stillborn. The tiny bodies were mummified, according to tradition, and laid to rest with their father in KV62.

Tut's successor, Aye, was an old family retainer and only ruled for four years. He too left no heir.

Next up was Horemheb, a military general. And oddly enough, he and his wife had no children either.

Egypt was a country that needed a strong, healthy, fertile king to take the reins firmly in hand and perpetuate the royal line. What to do?

Horemheb ended up adopting an army buddy as his heir, a man named Ramses, who became the first ruler of the 19th Dynasty. And so began the chapter in history that's often linked to the Bible, and to Ramses' grandson, Ramses II. That great pharaoh would reign for 67 years, father more than a hundred children with multiple wives, and mount military campaigns that covered Egypt in further glory.

It was a happy outcome, all in all. And yet, the haunting question remains: What would have become of Egypt if Tut and his wife had brought a strapping baby boy into this world?