Exclusive: Ancient port from Cleopatra’s time found underwater in Egypt

During her hunt for the Egyptian queen’s lost tomb, National Geographic Explorer Kathleen Martínez uncovered the sunken landscape near the ruins of Taposiris Magna.

For two decades, National Geographic Explorer Kathleen Martínez, an outsider in the world of archaeology, has searched for Queen Cleopatra’s tomb in hidden, underground sites that others discounted.

Many archaeologists think Cleopatra, Egypt’s last pharaoh and Ptolemaic ruler, died and was buried near the royal palace in Alexandria, where she was born and ruled. Martínez, a criminal lawyer-turned-archaeologist from the Dominican Republic, has been piecing together Cleopatra’s past like a crime scene to be deciphered. Her quest has led her instead to Taposiris Magna, an overlooked temple about 30 miles west of Alexandria in the Egyptian coastal town of Borg El Arab.

Now, miles offshore of Taposiris Magna, her team has discovered what Martínez believes may be a crucial clue in the 2,000-year-old mystery: a sunken port in the depths of the Mediterranean Sea. The finding, announced Thursday by the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, suggests that Taposiris Magna was not only an important religious center, but also a maritime trading hub, far more expansive than anyone previously realized.

“That makes the temple really important,” Martínez says, adding that it “had all the conditions to be chosen for Cleopatra to be buried with Mark Antony,” the Roman politician she loved and fought beside.

Back in 2022, Martínez and her team of Egyptian and Dominican excavators announced the discovery of a trove of artifacts and structures at the ruins of Taposiris Magna dating to Cleopatra’s reign—as well as a 4,300-foot tunnel, headed straight toward the sea.

Located about 40 feet underground, the tunnel was partly submerged and flooded by seawater. Inside they found ceramic jars and pottery from the time of the Ptolemies. Taken together with the most recent offshore discovery, Martínez says it suggests “the port was active during the time of Cleopatra and before at the beginning of the dynasty.”

To explore this unexpected intersection of land and sea, Martínez recruited the help of marine archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer at Large Bob Ballard, who famously discovered the Titanic. In their deep-sea operation they came across large and unmistakably man-made underwater structures, including a highly polished floor.

“This is one of those moments when you feel so alive,” Martínez said, floating on a raft at sea, in a scene captured for the upcoming documentary special, Cleopatra’s Final Secret, which premieres Sept. 25 at 10/9c on National Geographic and streams the next day on Disney+ and Hulu. “The divers are down—they’ve discovered a port!” she told Ballard over the phone.

“After 2,000 years nobody has ever been there,” Martínez told her team back on land. “We are the first ones.”

An extraordinary life—and mysterious death

Born in 69 B.C., Queen Cleopatra VII ascended the throne at 18. She was the final leader of the Ptolemaic period, the longest ruling dynasty in ancient Egyptian history, which came to power in 305 B.C. after Alexander the Great conquered Egypt. She was an “extraordinary woman” who also made powerful men afraid, says Martínez.

The Romans vilified Cleopatra, especially for her relationship with Julius Caesar. They characterized her as “a dangerous, exotic seductress who lured reputable Roman statesmen away from their responsibilities to the Republic,” says Sara E. Cole, associate curator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum, who is not part of the Taposiris Magna research team. “And Western historians and artists very much picked up that baton and ran with it.”

To Martínez, Cleopatra’s life is a lesson in fierce defiance of gender roles of her era. “She was a philosopher. She was a doctor in medicine. She was a chemist. She was a specialist in cosmetology.”

Following Caesar’s assassination, the queen had an 11-year passion-filled and politically charged romance with one of his generals and potential successors, Mark Antony.

The ancient writer Plutarch described Cleopatra’s encounter with Antony as she sailed up the river Cydnus “in a barge with gilded stern and outspread sails of purple, while oars of silver beat time to the music of flutes and fifes and harps.” Cleopatra greeted him under a golden canopy, dressed as the goddess Venus.

“Cleopatra’s appearances at sea were carefully orchestrated,” says Cole. “She created spectacles intended to awe audiences and to convey ideological messages. Appearing before Antony in a golden barge at Tarsus and overwhelming him with her riches was part of a strategy.”

Cleopatra’s political and personal relationship with Antony ended at sea as well. In 31 B.C., their naval forces faced off against the Roman ruler Octavian, Antony’s rival, at the Battle of Actium off the western coast of Greece, where Cleopatra commanded her own fleet.

Following their defeat, Antony fled to Egypt and is said to have stabbed himself with his own sword in Alexandria, later dying in Cleopatra’s mausoleum, in her arms. Threatened with captivity by the Romans, Cleopatra took her own life at age 39, some speculate by using snake venom, though that has never been proven.

The search for Cleopatra’s tomb

Plutarch wrote that Antony and Cleopatra were buried together in her mausoleum in Alexandria, but no evidence of her tomb has ever been found there. The city was struck by a major earthquake and a tsunami in A.D. 365, and today much of the historic royal quarter is submerged 20 feet underwater.

But in her pursuit for the tomb, Martínez also considered Cleopatra’s resistance to Octavian. Martínez thinks that rather than submit to Rome, the queen instead devised a plan to vanish, hiding her body along with Antony’s in a place the Romans would not even think to look.

“She had to choose a location where she could feel safe for her afterlife with Mark Antony,” says Martínez.

Martínez considered all the possible temples the queen could have reached from Alexandria within a day. She ultimately narrowed her search down to Taposiris Magna and in October 2005, her team began their search.

(Learn more about Kathleen Martínez and her search for Cleopatra)

The expedition led to a series of remarkable findings. Notably, Martínez’s team unearthed a foundation plate at the temple site, with an inscription in Greek and hieroglyphics that indicated the temple had been dedicated to the goddess Isis—a link that holds significance, since many considered Cleopatra a living embodiment of Isis.

To Martínez, it made sense that the queen would want her final resting place to be in the temple of Isis, the goddess that Cleopatra so deeply identified with.

“She didn’t want to die as a slave or a prisoner,” Martínez speculates. “She wanted to die as a daughter of Isis.”

At the temple, her team in collaboration with the Universidad Nacional Pedro Henríquez Ureña in Santo Domingo, has discovered hundreds of human remains, including mummies that were once covered in gold leaf, as well as pottery, and more than 300 coins, some bearing the image of Cleopatra. The ceramics date to around the time of Cleopatra’s rule, 51 to 30 B.C., the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced last December.

“So far, we have discovered more than 2,600 objects in a place where everybody believed there was nothing to be found,” Martínez says. “We have changed the history of the area so far, even though we have not discovered the tomb of Cleopatra. I have proved all those professors wrong.”

But “regardless of whether Taposiris Magna has anything to do with Cleopatra’s burial,” says Cole, “Martínez and her team appear to have been making significant discoveries there that have the potential to enhance our understanding of the Ptolemaic period in Egypt and of the temple complex itself.”

A port connected to Cleopatra

Martínez believes Cleopatra’s body was brought to Taposiris Magna and possibly carried through the tunnel, before being laid to rest, hidden and out of reach of the Romans. Over the centuries, at least 23 earthquakes struck the Egyptian coast between A.D. 320 and A.D. 1303, causing parts of Taposiris Magna to sink beneath the waves. Martínez’s latest discovery beneath the sea builds on two decades of evidence, broadening the search and reaffirming the temple’s prominence in Cleopatra’s era.

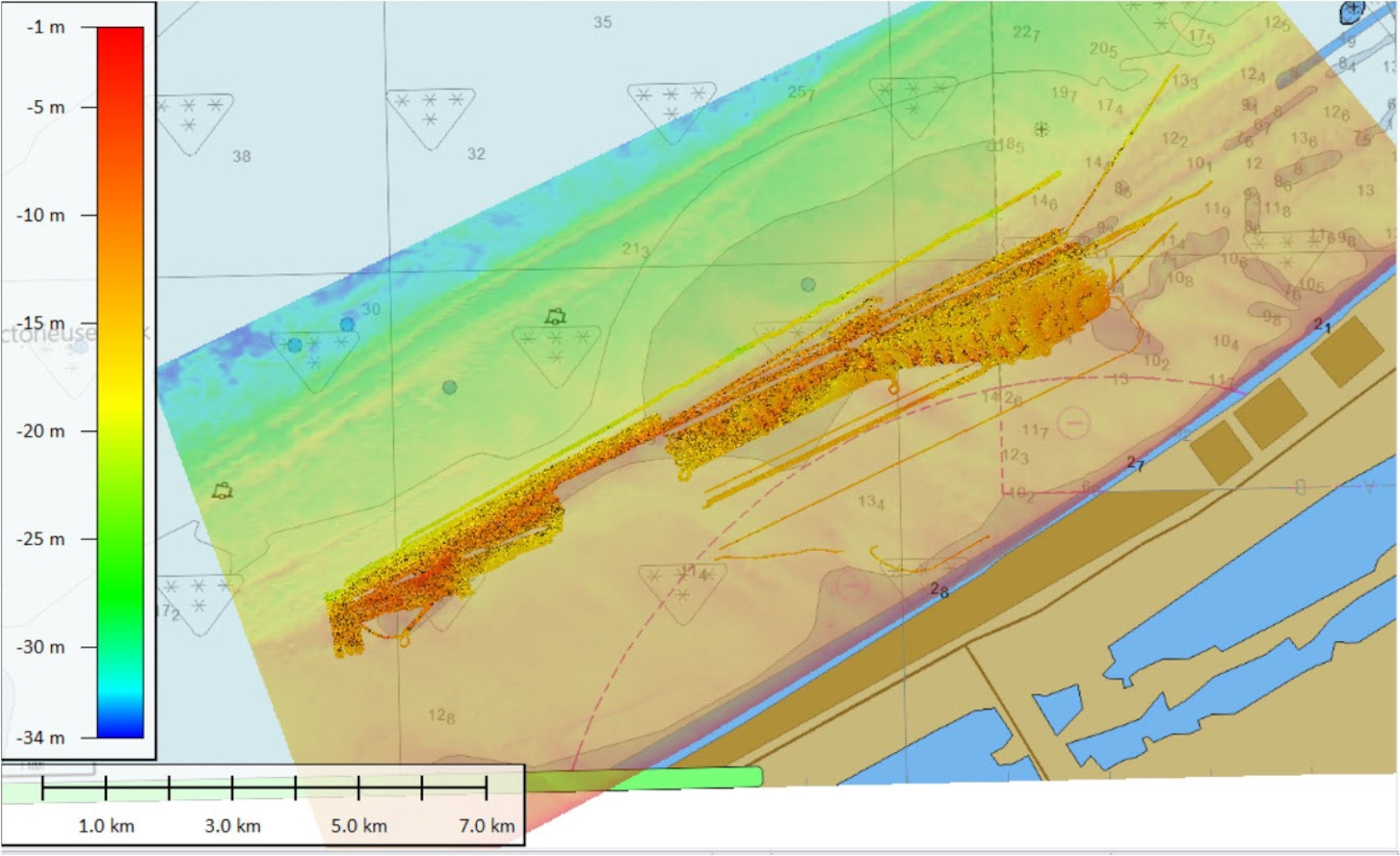

In their underwater search, which included help from the Egyptian Navy, Ballard says his team first found stone pockets where long ago fisherman had stored gear like fishing net and weights, indicating that the area must have once been a shoreline. Using sonar, they mapped a picture of the sea floor—where divers then discovered a profusion of ancient relics.

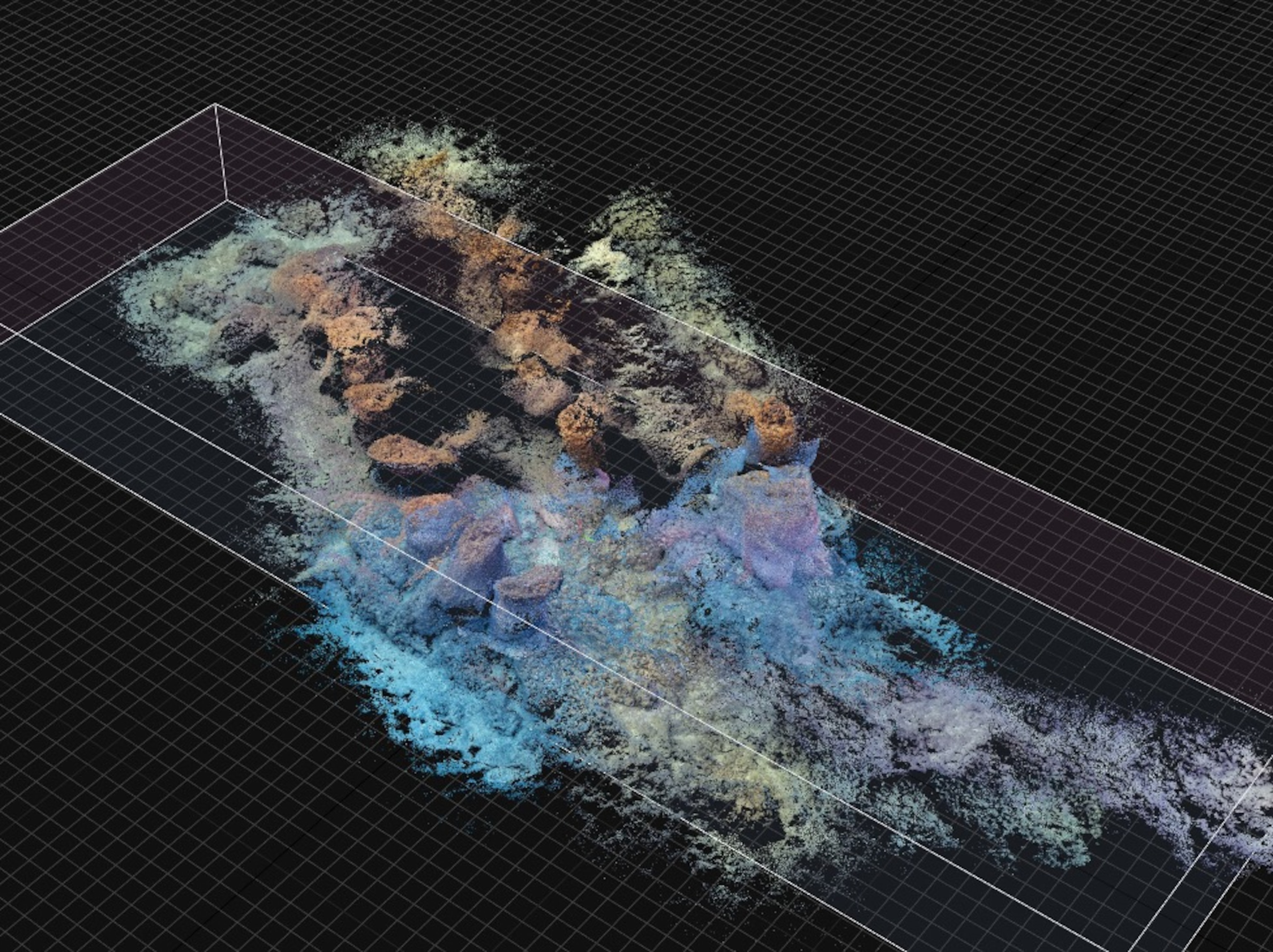

“We started seeing structures,” says Ballard, a series of colossal constructions covered in sediment, arranged in rows and over 20 feet high—cemented blocks, columns, smooth stone, as well as multiple anchors and amphora (containers used by the Greeks and Romans to transport goods). The evidence suggests it may have been a port connected to Taposiris Magna that was once used in Cleopatra’s time.

“We found it,” says Ballard, “and the tunnel pointed directly at it.”

One feature, dubbed "Salam 5" had several tall and flat, rectangular stone structures. Divers there also uncovered a basalt base resembling the pedestals of broken statues at the Taposiris Magna temple. Nearby, they found another stone structure with three pillars, which they called the “Three Sisters."

For Martínez, the discovery of this submerged port has brought her one step closer to her goal. “We will continue searching on land and underwater,” Martínez says. “This is the beginning of this huge task.”

Ballard has built a detailed technological map showing about six miles of key areas, with images of the port, submerged shoreline and other underwater structures. Following his map, Martinez and her team plan to begin new excavations with drills and divers focusing on "Salam 5" later in September.

“Nobody can tell me that Cleopatra is not at Taposiris Magna,” Martínez says. “To say that you have to excavate the whole area and not find her.”

Martínez remains steadfast in her mission. “I’m not going to stop.” Martínez feels that Cleopatra’s tomb is now closer than ever before. “For me,” she says, “it’s a matter of time.”