These Ghost Towns Once Thronged With Life

Economics, volcanoes, and even democracy can wipe a city off the map.

Isn’t it a tad creepy to be obsessed with ruins? Aude de Tocqueville doesn’t think so. For her, they hold a mysterious, poetic fascination that no living city can match. In her new book, Atlas of Lost Cities: A Travel Guide to Abandoned and Forsaken Destinations, de Tocqueville sets off on a journey of exploration to 44 places that once thronged with life but now lie dead and often buried. On the way, she discovers that, like us, cities are mortal. (Experience Chernobyl’s haunting ruins in 360-degree photos.)

Speaking from her home in Paris, the French writer explains how abandoned cities appeal to our imaginations, how a town in Quebec was voted out of existence, and how nature always reasserts itself among the ruins.

(Pictures: Centralia Mine Fire, at 50, Still Burns With Meaning)

We have to get one thing straight immediately—are you a descendant of Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote the famous travelogue, Democracy in America?

[Laughs] I am not a direct descendant of Alexis de Tocqueville. We are from two different branches of that family. Unfortunately! Because he was a great man and I’m a fan of everything he wrote.

You say, “Fond as I am of cities … I am even fonder of dead cities.” Are you a morbid person by nature?

[Laughs] Absolutely not! On the contrary, I’m extremely cheerful and a great lover of life. To excess, my husband would say. [Laughs] The reason I’m fascinated by ghost towns is because they appeal enormously to the imagination. As you walk through them, you can imagine all kinds of things. You can make them your own, invent their life, their history, the people who lived there. Unlike inhabited cities and towns, there are no limits.

I also love lost cities because I’m mad about architecture. Depopulated and abandoned, these towns often reveal impressive structures and architectural remains. Take Fatehpur Sikri in India, for example. Devoid of its palace wall hangings and the animation of its inhabitants, it is reduced to marble, stone, and infinite silence. It is breathtakingly beautiful.

What are the different reasons a city can vanish?

There are four main reasons for the demise of a city: Natural disaster, as in the case of Bam in Iran or Balestrino in Italy, which both disappeared as the result of earthquakes; economic problems, as with the gold rush towns in the United States, where the depletion of the mines robs a place of the very reason for its existence; human folly, of which there are numerous—often terrifying—examples. Epecuén, a charming lakeside resort in Argentina, was submerged because the flood-protection barriers were neglected. Kantubek, in Uzbekistan, the site of a biological weapons research center, was evacuated in a hurry following a series of laboratory accidents.

A town can also die as the result of the death of a civilization, as was the case with a number of Roman cities and also cities in South America such as Tikal, a Mayan center that disappeared because its civilization simply ran out of steam.

Pompeii symbolizes a place obliterated by a natural disaster. But other forces threatened what remained of the city, didn’t they?

Following the well-known eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii was the victim of a new and sorry catastrophe. When I visited, whole sections of the site were closed because buildings were in danger of collapsing as a result of the failure to renovate them. The Italian government could no longer afford to maintain this ancient city that has taught us so much about how the Romans lived 2,000 years ago.

The discovery of precious metals can lead to the hasty creation of a city—and then its abandonment. Tell us about Calico, in California.

Whether in America, Europe, or Africa, the discovery of precious metals has always led to the extremely rapid—and often shoddy—construction of towns, which are usually destined to disappear just as quickly as they sprang into life.

Calico in California is a striking example. Born in 1881 and abandoned in 1907, the town had 10 bustling years of hotels, stores, saloons, and prosperous existence. Then it was suddenly deserted. What is strange is its second life because, unlike us, a town can be reborn.

Its ghost-town character, its wooden façades, and Western atmosphere gave a local farmer the idea of turning it into a tourist site. Over the years, the original town was reconstructed exactly as it was and today it has become a much-loved tourist attraction. In 2005, Arnold Schwarzenegger, then governor of California, even designated the place the “official ghost town of the Silver Rush.”

In 1982, the zip code of Centralia, in Pennsylvania, was officially withdrawn, marking the end of its existence. There’s an amazing story behind that, isn’t there?

The story of Centralia is particularly spectacular. It’s incredible to think that this town died as the result of an underground fire in 1962, which has been impossible to extinguish ever since. A group of municipal employees set fire to a pile of rubbish in a cemetery. The fire spread underground because Centralia is a former mining town and riddled with subterranean galleries. Initially, no one realized the fire had spread. But over the next few months, cracks appeared in the ground from which smoke and—most worryingly—carbon monoxide were released. In 1981, the entire town was evacuated and a year later the zip code was discontinued. The craziest thing is that smoke is still escaping from the fissures in the ground. As a result, Centralia has become a tourist attraction and has even inspired a video game.

Some cities are sacrificed for economic reasons. Tell us about Tignes in your native France and Shi Cheng in China.

In 1952, Tignes, an adorable little mountain village in the French Alps, with traditional wooden chalets, was engulfed within the space of a few minutes by the waters of a dam designed to power a hydroelectric plant.

The same thing happened in 1959 in China to the city of Shi Cheng. There, however, a city more than a thousand years old disappeared beneath the waters of an artificial lake. For almost 40 years, nothing more was heard of Shi Cheng until one day divers rediscovered its magnificent and, most importantly, well-preserved remains almost 40 meters below the surface. I would love to have been that first diver to have seen the city. [Laughs] Today, you can go on scuba excursions to the submerged ruins.

Another cause for a city vanishing is nuclear catastrophe. Tell us about Pripyat.

Human folly has been the cause of instant and terrible destruction, as in the case of Pripyat, in Ukraine, and also Fukushima. In 1986, the inhabitants of Pripyat were forced to leave their homes within a quarter of an hour. They were told: “You’ll be returning in three days’ time.” But they have never been able to return, due to the continued radioactivity: The zone has never undergone decontamination. Today, nature has reasserted itself. Numerous animals now live among the automobile carcasses and children’s toys that lie abandoned on the ground. It’s a truly pitiful sight, brought about by the negligence of mankind—and our inability to take good care of our planet.

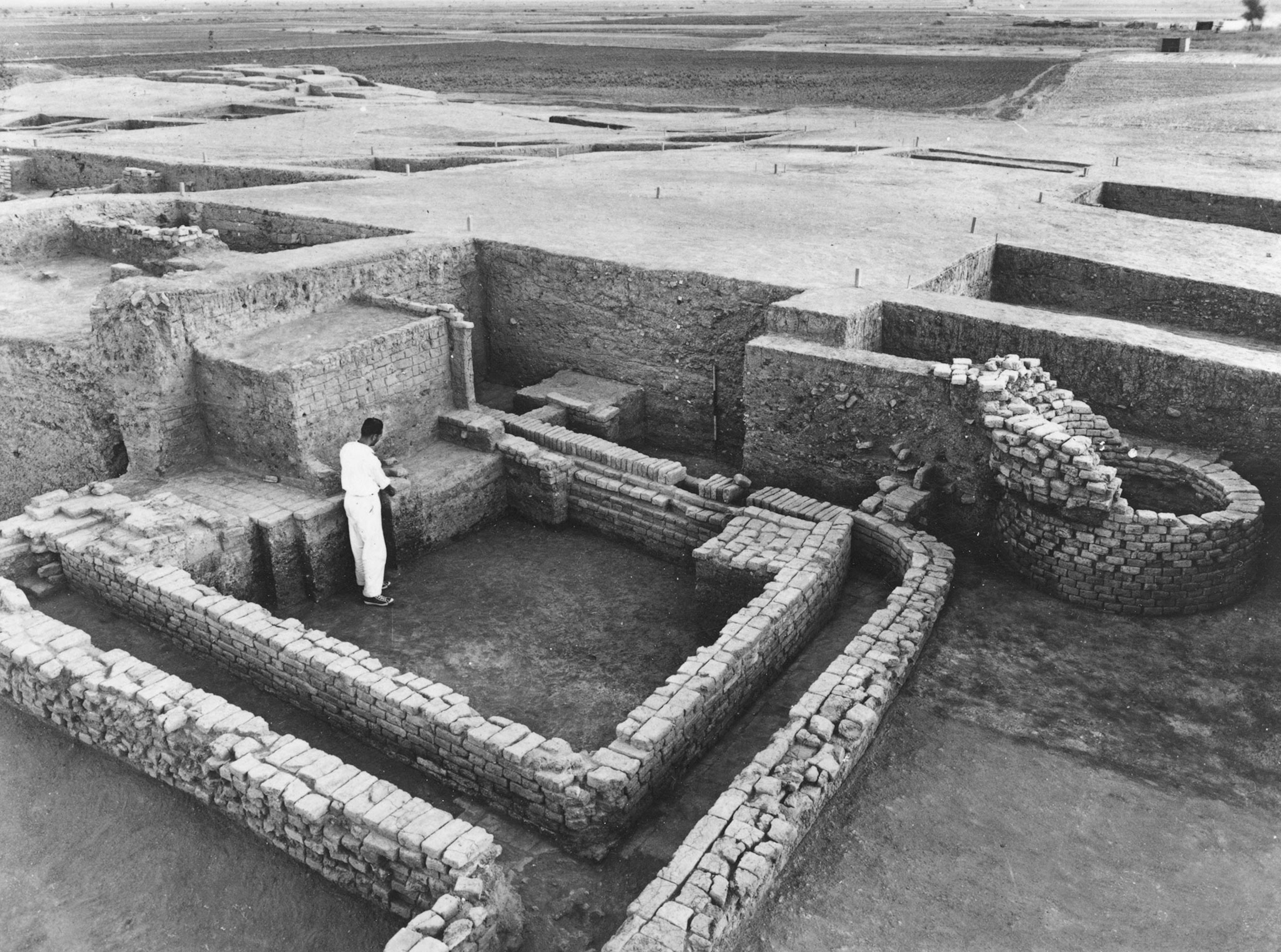

Shifting geography can also cause a place to vanish. Talk about Lothal, in India.

Lothal is a good example of a city that disappeared as the result of a natural movement of the earth. The region around it was submerged little by little by repeated floods until they eventually wiped out the city. This is also the story of one of the world’s most ancient civilizations, the Indus, which flourished between 3300 and 1900 B.C.

What fascinates me about lost cities is that, like us, they are born in a particular place in the world, grow up, and then die. These towns touch us emotionally because they are so ephemeral, just like ourselves.

Gagnon, in Canada, has a very unusual reason for vanishing: It was voted out of existence. Tell us the story.

How can a town be erased from the map of the world? Gagnon came into being in 1957, following the discovery of an iron ore deposit. But as soon as this deposit was exhausted, this remote town was abandoned. And in 1984, a vote of the National Assembly of Quebec simply wiped it off the map, even though there were still more than 4,000 inhabitants living there!

Today, Gagnon definitely deserves to be called a “ghost town.” Not a single dwelling or road remain as a reminder that a town once existed in this remote region of the North Coast of Quebec. But, as fate would have it, in 1987 a direct route to this inaccessible region of the far north opened up—in other words, only three years after the total destruction of Gagnon by bulldozer.

Some cities, like Jeoffrecourt, in France, you were not able to visit, were you?

Jeoffrecourt is really a special case, because it has technically never existed! Located in northern France, it was created from scratch as a place to train soldiers from all over Europe in urban warfare. There is everything in this town—a mall, a place of worship, even an RV park—but it has never been inhabited. It even includes a section of the Hindenberg Line, one of the defensive positions established by the German rearguard in 1916. It’s a very strange place, like a video game.

In all, you describe 44 lost cities. How many did you visit yourself?

I am a compulsive traveler, and most of my books have been travel books. But I traveled less for this book than for others, because this is not meant to be a travel guide. It contains neither addresses nor tips. It is a book to be read at home, telling what I hope are moving, poetic, and mysterious stories of towns that have been abandoned. Of course, I hope it will inspire readers to go and discover these places for themselves. Or, in the case of the more distant spots, that it will make them dream.

Which lost city left the deepest impression on you?

As you have gathered, I have a particular fondness for ruins, like those of Carthage, Djémila, and Marib, which I have visited. Along with Fatehpur Sikri in India, it is perhaps this town in Yemen that affected me the most. There is not much left to see of the ancient capital of the kingdom of Sheba: a few columns of rammed clay, a few Sabaean inscriptions that can be made out on the stones of the buildings. But the air is uniquely arid (Marib is in the heart of the desert) and the history extraordinarily rich: This was the crossroads of the Incense Route.

The mind conjures up images of caravanners resting in the cool shade of palm trees at the foot of the ramparts. Today, there are just goats and a few children, who are proud to show off the ruins. But one way and another these abandoned cities continue to live: Nature is flourishing once again at Pripyat, Italians grow vegetables among the ruins of Pompeii, and there is an annual music festival in the ruins of Djémila. Life doesn’t desert any place forever.

This interview was translated from the French and edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.