What it was like to visit Petra more than 100 years ago

Less than a century after it was rediscovered, National Geographic's correspondent explored the ruins of Petra and found its beauty almost indescribable.

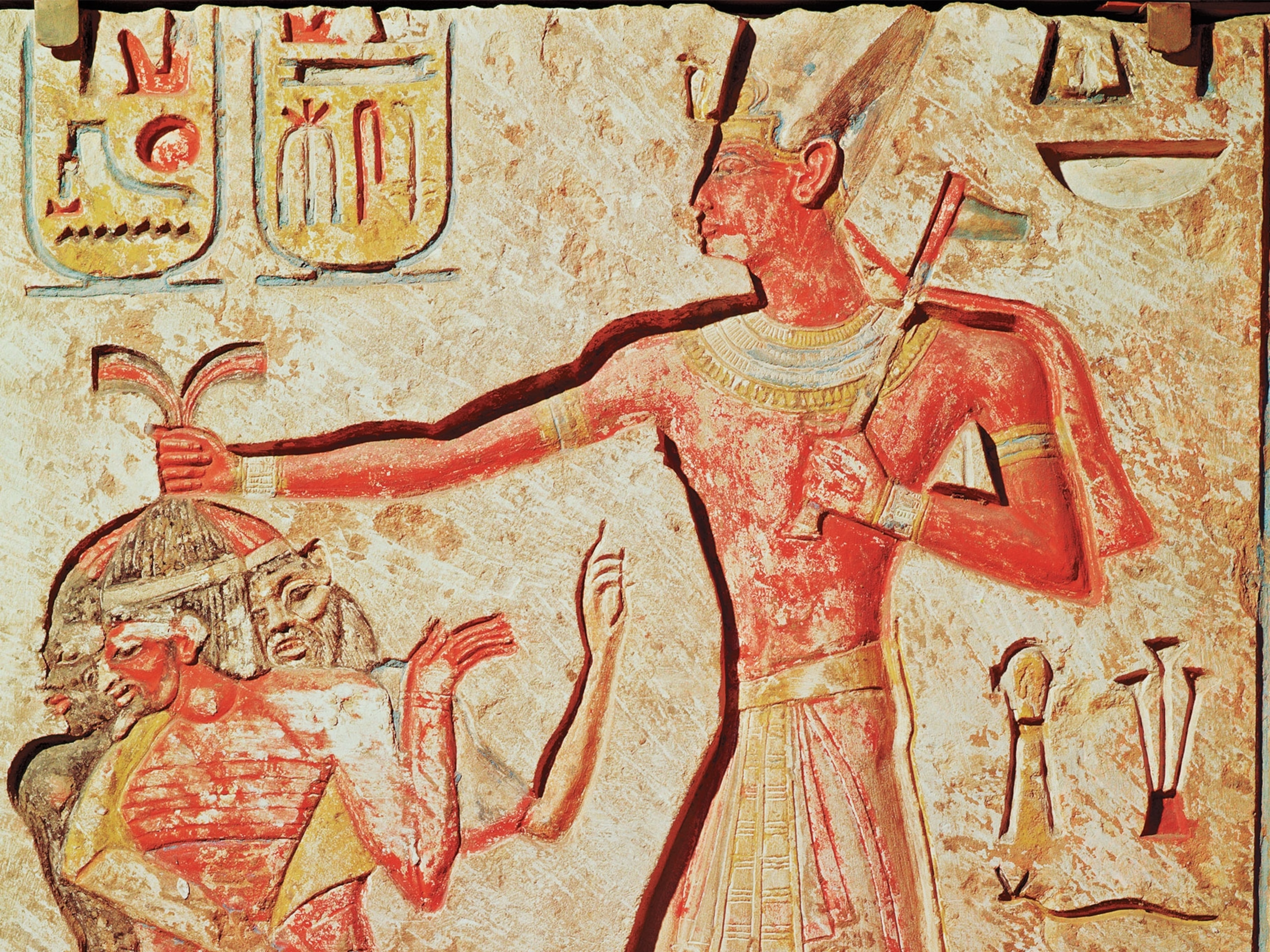

The highlands east of the Jordan River are strewn with ruins marking the rise and fall of successive civilizations—Semitic, Greek, Roman, Christian, Mohammedan, and Crusader. These ruins have been preserved for the modern explorer by the tides of nomadic life, which have swept up from the Arabian desert; but at the southern end of this no-man's land, deep in the mountains of Edom, lies one of the strangest, most beautiful, and most enchanting spots upon this earth—the Rock City of Petra. Its story carries us back to the dawn of human history. When Esau parted in anger from Jacob he went into Edom, then called Mount Seir, and after dispossessing the Horites became the progenitor of the Edomites, who remained the enemies of the children of Israel for a thousand years. These Edomites had princes, or kings, ruling in the Rock City while the children of Israel were still in Egyptian bondage. Some of the darkest maledictions of the Old Testament prophets are those aimed at Edom.

A great ‘safe deposit’

In the days of the Nabatheans, Petra became the central point to which the caravans from the interior of Arabia, Persia, and India came laden with all the precious commodities of the East, and from which these commodities were distributed through Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and all the countries bordering on the Mediterranean, for even Tyre and Sidon derived many of their precious wares and dyes from Petra. It was at that time the Suez of this part of the world, the place where the East and the West met to trade and barter. It was also in fact a great "safe deposit" into which the great caravans poured after the vicissitudes and dangers of the desert. Its wealth became fabulous, and it is not without some good reason that the first rock structure one sees in Petra, guarding the mysterious entrance, is still called "Pharaoh's Treasury." It must have been the Nabatheans who developed the natural beauties of the situation and increased the rock-cut dwellings and temples and tombs to the almost interminable extent in which they are found today.

(Who built the ‘lost city’ of Petra—and why did they leave?)

The palmy period of the Nabatheans extended from 150 B. C. to 106 A. D., when the Romans conquered the country and city, extended two Roman roads into it, and established the province of Arabia Petra. The Rock City was always to these regions and peoples what Rome was to the Romans and Jerusalem to the Jews. Horites, Edomites, Nabatheans, and Romans have all rejoiced and boasted in the possession of this unique stronghold and most remarkable city of antiquity.

When Rome's power waned and the fortified camps on the edge of the desert were abandoned, no doubt the soldiers were withdrawn from such cities as Petra. Then the Romanized Nabatheans or Nabatheanized Romans held their own against the desert hordes as long as they could, and went down probably about the same time as the Greek cities of the Decapolis (636 A. D.). From the time onward Petra's history becomes more and more obscure, and for more than a thousand years Edom's ancient capital was completely lost to the civilized world. Until its discovery by Burckhardt, in 1812, its site seems to have been unknown except to the wandering Bedouin.

The silk or entrance defile

The entrance to the Rock City is the most striking gateway to any city on our planet. It is a narrow rift or defile, bisecting a mountain of many-hued sandstone, winding through the rock as though it was the most plastic of clay. This sik, or defile, is nearly two miles long. Its general contour is a wide semicircular swing from the right to the left, with innumerable short bends, having sharp curves and corners in its general course.

The width of the Sik varies from twelve feet at its narrowest point to 35 or 40 feet at other places. Where the gloomy walls actually overhang the roadway and almost shut out the blue ribbon of sky, it seems narrower, and perhaps at many points above the stream the walls do come closer than 12 feet. Photographs of these narrower and darker portions of the defile are impossible. Only where the walls recede and one side catches the sunlight was it possible to secure any views that would reveal the actual beauties of the place. Then no camera could be arranged to take in the whole height of the canyon. The height of the perpendicular side cliffs have been estimated at from 200 to 1,000 feet. Heights, like distances, in this clear desert air are deceptive, but after many tests and observations we are prepared to say that at places they are almost sheer for 300 to 400 feet.

Seen at morning, at midday, or at midnight, the Sik, this matchless entrance to a hidden city, is unquestionably one of the great glories of ancient Petra. Along its cool, gloomy gorge file the caravans of antiquity—from Damascus and the East, from the desert, from Egypt and the heart of Africa. Kings, queens, and conquerors have all marveled at its beauties and its strangeness. Wealth untold went in and out of it for centuries, and now for over thirteen hundred years, it has been silent and deserted.

(Like Petra, these 10 stunning UNESCO sites were immortalized on screen.)

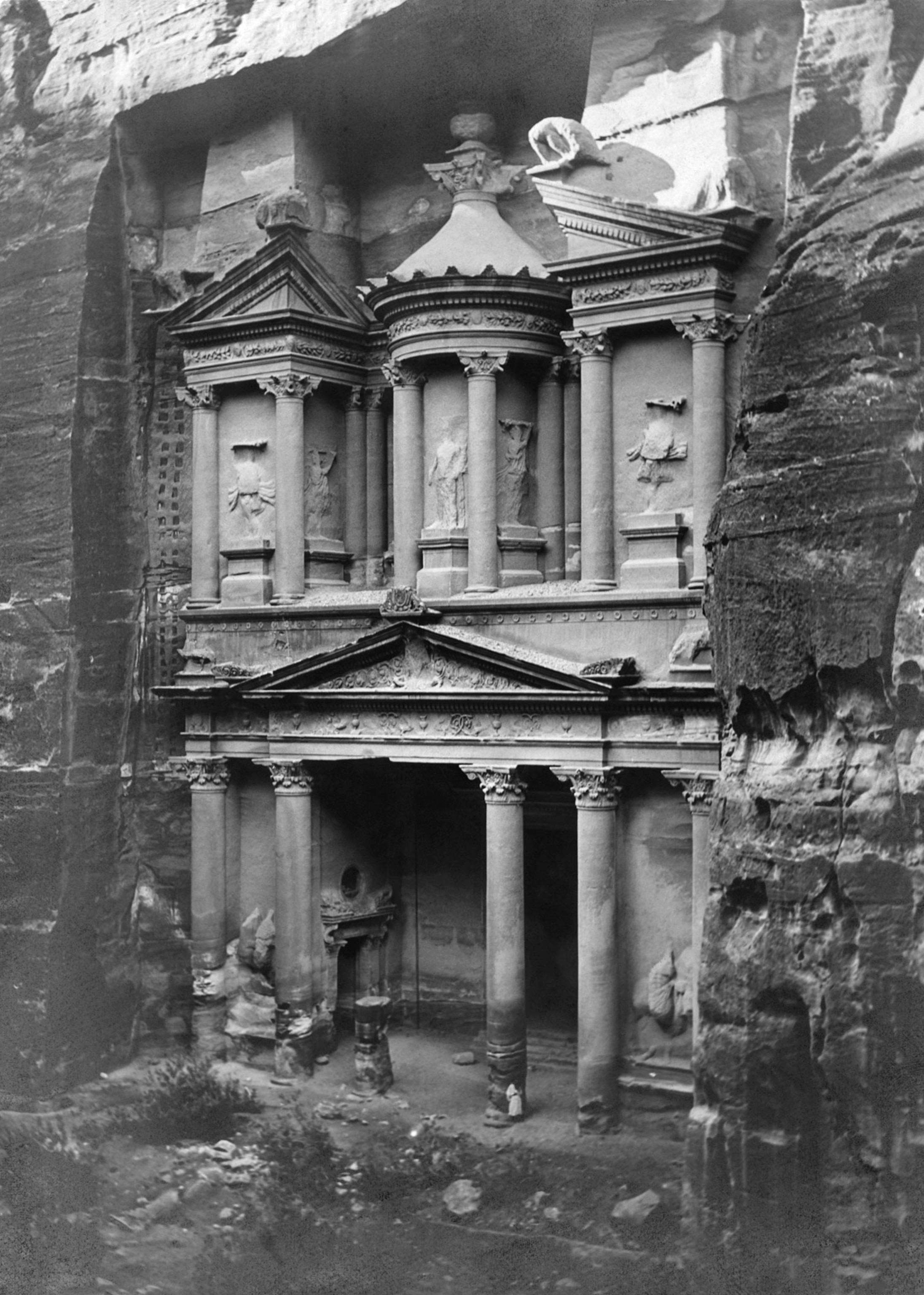

Pharoah’s Treasury

The first time we picked our way into this matchless defile we wandered on amazed, enchanted, and delighted, not wishing for, not expecting, that anything could be finer than this, when a look ahead warned us that we were approaching some monument worth attention, and suddenly we stepped out of the narrow gorge into the sunlight again. There in front of us, carved in the face of the cliff, half revealed, half concealed in the growing shadows, was one of the largest, most perfect, and most beautiful monuments of antiquity—Pharaoh's Treasury. Almost as perfect as the day it came from beneath the sculptor's chisel, fifteen hundred or two thousand years ago; colored with the natural hues of the brilliant sandstone, which added an indescribable element to the architectural beauty; flanked and surmounted by the cliffs, which had been carved and tinted in turn by the powers of nature; approached by the mysterious defile—it is almost overpowering in its effect.

Descriptions of the width and height and the details of this monument of antiquity may enable many to reproduce for themselves some of its striking features; but neither language, measurements, nor pictures can give more than a bald idea of the temple and its charming surroundings. The secret of its magic seems to be the culmination of man's best efforts with the powers and beauties of nature.

(How one explorer tricked his way into Petra, a secret for centuries.)

Located at the end of a long and difficult journey, whether one comes from the valley of the Euphrates, from Sinai, from Egypt, or from any point of Syria east or west of the Jordan; set in the mountains of mystery, at the gateway of the most original form of entrance to any city on our planet; carved with matchless skill, after the conception of some master mind; gathering the beauties of the stream, the peerless hues of the sandstone, the towering cliffs, the impassable ravine, the brilliant atmosphere, and the fragment of blue sky above—it must have been enduring in its effect upon the human mind. We saw it in its desolation, a thousand years after its owners had fled—tempest, flood, and earthquake having done their worst, aided by the puny hand of the pandering Arab, to mar and disfigure it—and we confess that its impression upon our hearts and memory is deathless.

To portray the marvelous coloring of these masses of sandstone and to give anything like a correct view of this unique feature of Petra is something we attempt with misgivings. From the moment we sighted the great castellated mass in which the city lies hidden until we took our last glimpse from the highlands above, we never ceased to wonder at the indescribable beauties of the purples, the yellows, the crimsons, and the many-hued combinations. Whether seen in the gloom of the Sik, or the brilliant sunshine, that seemed to kindle the craggy, bristling pinnacles into colored flames, they continued to inspire our surprise.

Travelers have vied with each other in their attempts to describe these beauties. After the solid colors of red, purple, blue, black, white, and yellow, the never-ending combinations are best compared with watered silk or the plumage of certain birds.

(Discover the epic path that crosses the Middle Eastern kingdom of Jordan.)

We shall be listened to if we say with all soberness that "the half was never told" of the effect of this many-hued landscape; for as we saw it glistening with the rain drops after the showers, we saw it before the sunrise, we saw it under the noonday sun, and we noticed, as perhaps no one had done before us, the way in which these ancient sculptors fixed the levels of their tombs and temples and dwellings so as to make most artistic use of the more beautiful strata in the mountain walls, and we marveled again and again, in the never-ending ravines, how these ancient dwellers consciously practiced a kind of landscape gardening, where, instead of beautiful effects produced by banks of fading flowers, all was carved from the many-hued and easily wrought solid stone, which took on new beauties as it crumbled away.

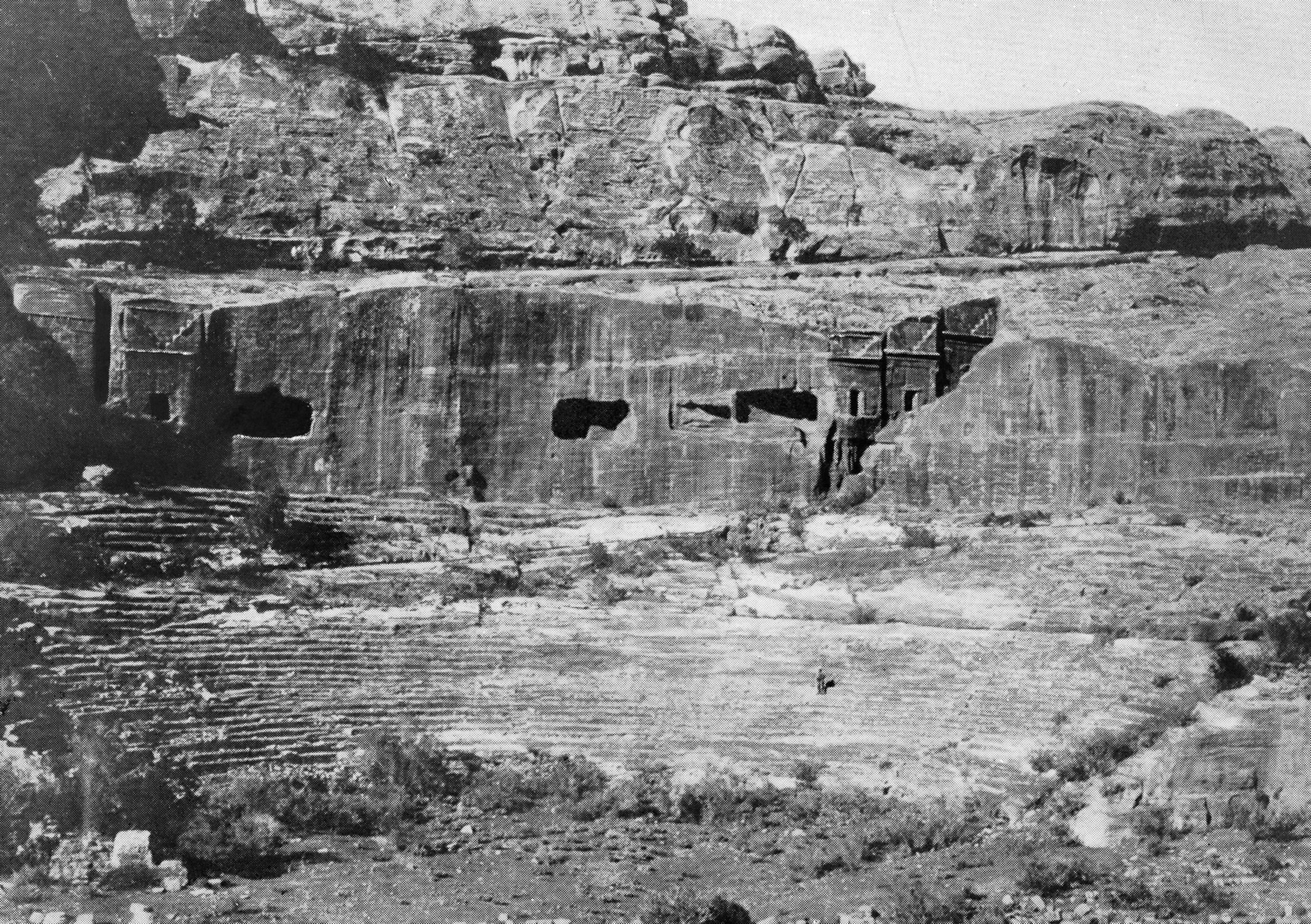

The great theater

Not far from Pharaoh's Treasury is a great theater cut in what may be called the Appian Way of the city. It stands among some of the finest tombs—a theater in the midst of sepulchers. The floor of the stage is 120 feet in diameter. Fully 5,000 spectators could have found comfort in the thirty three rows of seats. Here also the coloring of the sandstone is brilliant, and at certain places in the excavation the tiers of seats are literally red and purple alternately in the native rock. Shut in on nearly every side, these many-colored seats filled with throngs of brilliantly dressed revelers, the rocks around and above crowded with the less fortunate denizens of the region, what a spectacle in this valley it must have been! What an effect it must have produced upon the weary traveler toiling in from the burning sands of the desert, along the shadows of the marvelous Sik, past the vision of the Treasury, and into the widening gorge that resounded with the shouts of the revelers, in the days of its ancient glory.

The eastern wall of the valley, near the entrance, rises to a height of more than five hundred feet. For a length of a thousand feet the face of the cliff is carved and honeycombed with excavations to a height of three hundred feet above the floor of the valley.

Here are found some of the most impressive ruins in the city. The Urn tomb in the center has in the rock behind it a room over 60 feet square, whose beautifully colored ceiling can be compared to a great storm in the heavens. The Corinthian tomb and temple are among the largest and most beautifully colored monuments in any of the walls.

The Deir is reached by one of the great ravines up which winds a path and stairway until an elevation of 700 feet is attained. A small plateau opening toward the south gives an extended view of Mount Hor and all the southern end of the Dead Sea cavity. The spot is wholly inaccessible except by the one rocky stairway and winding path.

The Deir is carved from the side of a mountain top, but not protected by any overhanging mass. It is larger than the Treasury. but not nearly so fine in coloring or design. It is impressive in its size and its surroundings, but cannot be called beautiful.

Finally, if you will remember that originally the whole valley, from its beginning at the door of the Sik until its exit among the fissures at the southern end of the Dead Sea, is one huge excavation made by the powers of nature, the torrent and the earthquake; and that the hand of time, the frost, the heat, and the tempest have been busy through the ages cracking, smoothing, chiseling mountaintop, deep ravine, and towering cliff into a myriad of fantastic forms, and that the subtler, silent agencies of Nature's alchemy have been adding the most brilliant hues to moldering sandstone strata. You cannot but be charmed and amazed at the result of her handiwork.

Then when you enter the city by the winding valley of the Sik, gaze at the stupendous walls of rock which close the valley and encircle this ancient habitation, and mark how man himself, but an imitator of Nature, has adorned the winding bases of these encircling walls with all the beauty of architecture and art—with temple, tomb and palace, column, portico and pediment—while the mountain summits present Nature in her wildest and most savage forms, the enchantment will be complete, and among the ineffaceable impressions of your soul will be the memories of this silent, beautiful "rose-red city half as old as time."

(The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?)