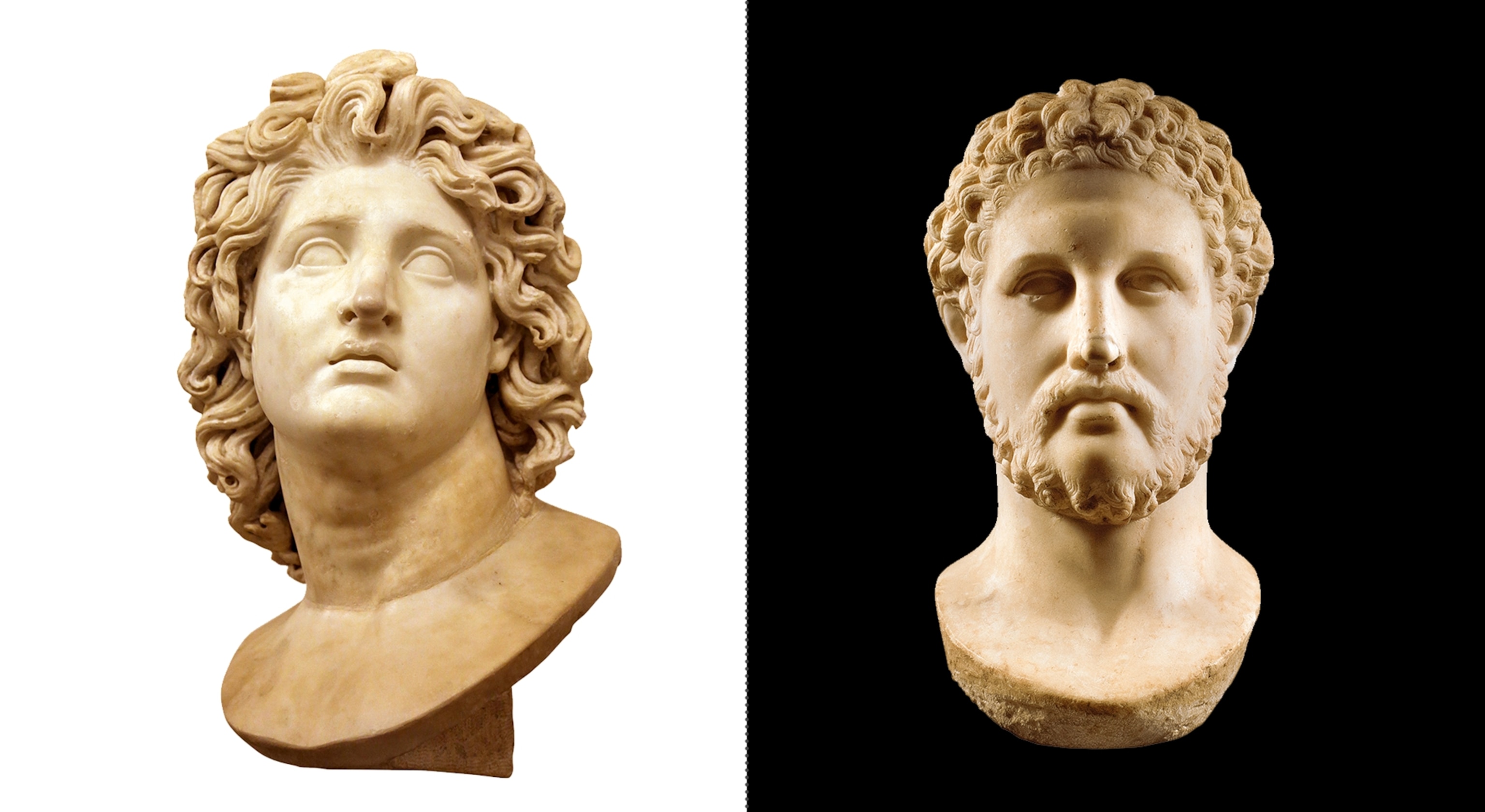

How Alexander the Great's daddy issues reshaped the world

Alexander had a love-hate relationship with his father, King Philip II of Macedonia. While at times he appeared to be the clear heir, polygamy, exile, and an assassination made Alexander's path to power much more complicated.

Alexander the Great’s childhood has often been presented as a time of conflict between his parents, Philip II and Olympias. But this image, so often explored in novels and films, is likely exaggerated. Most of the sources preserved from this period are Athenian; no Macedonian writings have survived. So it was Philip’s enemies, with their subjective and even manipulated accounts, who shaped what we know about the intricacies of the Macedonian court. Nevertheless, dynastic tensions evidently ran high at the court of Philip, and one factor that had an impact on family relations was the practice of polygamy.

Marriage in Macedonia was a politically oriented institution, often used to establish diplomatic relations or ensure royal succession. Philip had seven wives but among them they bore him only two sons: Philip III Arrhidaeus and Alexander. Some sources say there was a third, Caranus, who may have died in childhood, although his existence is doubtful.

The lack of a clear system for royal succession and the multitude of wives without any formal hierarchy increased conflict at court. Becoming the best candidate to inherit the throne depended on several factors. Foremost was to be a member of the Argead dynasty, descended from Perdiccas I, who founded the kingdom of Macedonia in the seventh century B.C. Until Alexander’s death, all the kings of Macedonia had come from this family.

(Who was Alexander the Great?)

A second determining factor was the political prestige and importance of the maternal family. If the mother belonged to Macedonian nobility, support for an heir among the local aristocracy would be stronger. The sons of foreign women, such as Olympias, who came from Epirus, had in principle, less legitimacy. A third factor was the support a potential heir could muster among different factions within the kingdom.

This was key to ensuring political stability. Although the final decision rested with the monarch, his wives had a role in placing their male offspring in the race for succession. In this context, Alexander had a relatively straightforward path to power. His older half-brother Arrhidaeus was mentally incapacitated. Some sources attribute this to Olympias poisoning him in order to remove him as a candidate for the throne. Alexander, meanwhile, was brought up in a manner befitting a Macedonian prince. His training combined traditional disciplines such as grammar, rhetoric, arithmetic, and geometry with physical activities like hunting and battle training. The most notable of his teachers was Aristotle, to whom Philip entrusted the education of his son for three years.

Smooth sailing, at first

While very young, Alexander was able to put into practice the solid education that his father had so carefully designed. Around 340 B.C., during one of Philip’s numerous absences, Alexander had to act as regent at barely 16 years old. The sources describe how he led a successful campaign against the Thracian tribe of the Maedi and went on to establish a military settlement he called Alexandroupolis Maedica, the first of many cities he would found and name after himself. His promising career continued with the Battle of Chaeronea.

Olympias, "perfidious" or maligned?

The couple would later become yet more estranged after the clash between Alexander and Philip on the eve of Philip’s wedding with Cleopatra. Olympias accompanied her son into exile and, according to the third-century A.D. Roman historian Justin, tried to conspire against her husband from Epirus. Some sources depict Olympias as the brains behind the plot to kill Philip and the subsequent brutality to Philip’s seventh wife Cleopatra. It is likely that behind the larger-than-life vengefulness attributed to her, a skillful political operator was at work.

His father assigned him to lead the left wing of the Macedonian army to disrupt the advance of the Sacred Band of Thebes. After the victory, it was Alexander who, in the company of the general Antipater, took charge of the subsequent negotiation in Athens—a precursor to the League of Corinth, a coalition of Greek city-states under Philip. The young prince was already shaping up to be a worthy successor to his father.

It seems that up until this moment, Philip, Olympias, and Alexander had a reasonably good relationship. In fact, after the victory of Chaeronea, Philip had a symbolic monument, the Philippeion, built to celebrate the triumph of the Argead dynasty over the Greeks. The circular stone building includes statues of Philip, his parents, Amyntas III and Eurydice I, Alexander, and Olympias. To include a statue of Alexander here was a clear indication that Philip had singled Alexander out as heir to the throne.

(This Wonder of the Ancient World shone brightly for more than a thousand years.)

Alexander, victorious at Chaeronea

The first clash

Shortly after erecting the lavish tribute, Philip made a controversial decision: to marry a young woman from the Macedonian aristocracy called Cleopatra. To date, none of Philip’s wives had been Macedonian: Audata was Illyrian, Phila was from Elimea, Philinna and Nicesipolis were from Thessaly, Olympias (Alexander’s mother) was a princess of Epirus, and the sixth, Meda, was of Thracian origin. With Cleopatra it was different; Greek writer Athenaeus, notes that Philip was “violently in love” with her.

(Alexander the Great's warrior mom wielded unprecedented power.)

But, as in previous marriages, there was likely a political purpose too. Earlier Philip had shown no interest in marrying into to the Macedonian nobility, but now he considered it necessary in order to garner support before beginning his invasion of Persia. Cleopatra was the niece of Attalus, one of the generals who was to lead the offensive, so this link was key. The decision to marry Cleopatra provoked unease in Alexander’s circle, since any future male descendant could jeopardize his succession.

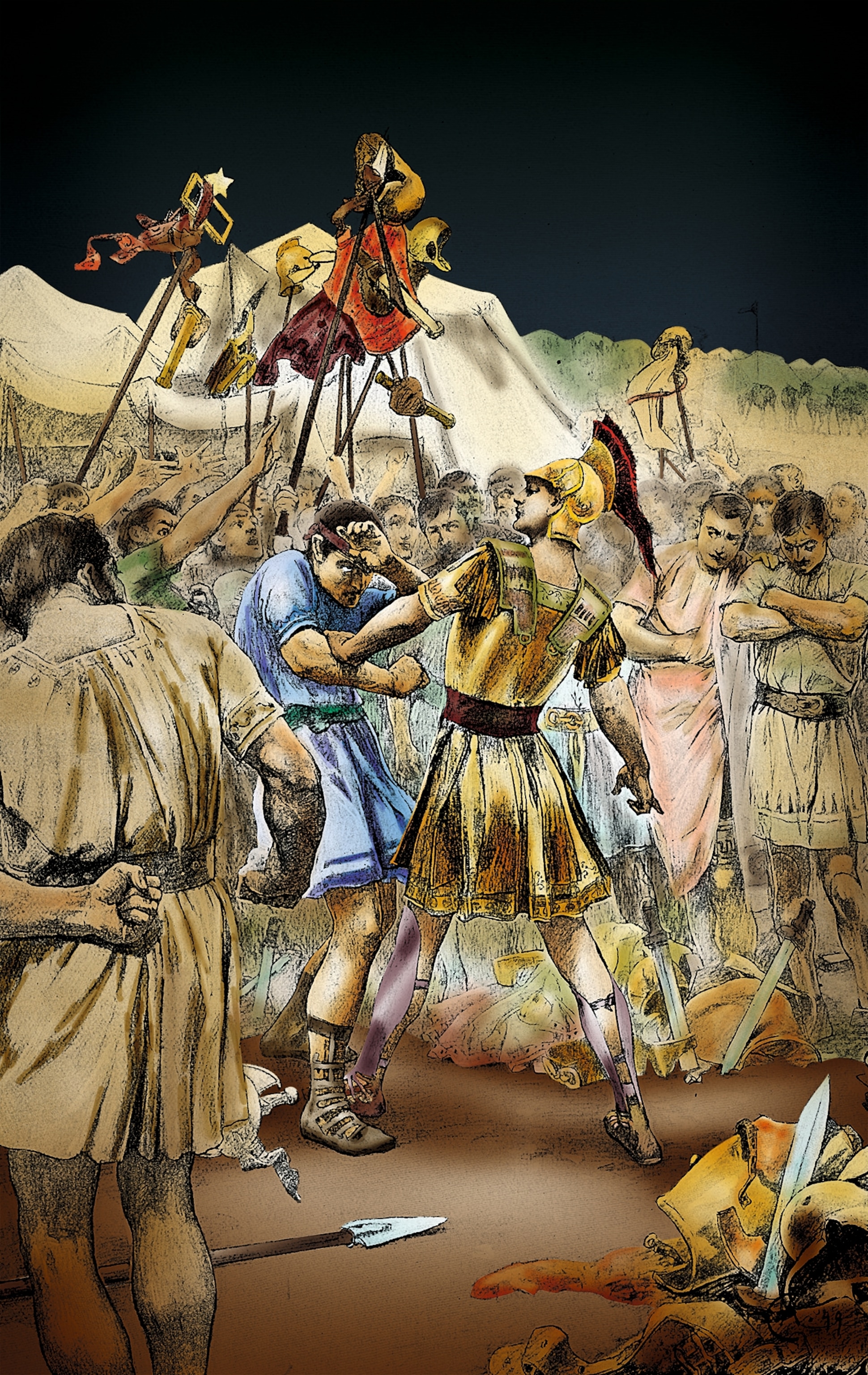

The situation exploded during a banquet on the eve of Philip and Cleopatra’s wedding. Attalus, Cleopatra’s uncle, took advantage of the toast to proclaim his desire for Cleopatra to ensure “a legitimate heir” for the kingdom. Alexander, who interpreted the statement as a personal attack, lashed out and was publicly reprimanded by Philip, who was perhaps compelled by the norms of hospitality. After this serious disagreement, Alexander went into exile with his mother Olympias, and possibly with his closest friends. First he took refuge at the court of his uncle, Alexander of Epirus, and then he was able to stay with Langarus, king of the Agrianians.

(Were Alexander the Great and Hephaestion more than friends?)

The banquet that set father against son

The second confrontation

It’s possible that there were other reasons behind Alexander’s exile. It’s been suggested that Philip wanted to leave Alexander in charge of Greek affairs during the invasion and that his son had not taken well to this important but secondary role. Whatever the true reasons for the exile, Philip knew he couldn’t venture into Asia before putting his own house in order, so he opened the way for Alexander to return.

Peace was short-lived, however, according to a somewhat confusing account from Plutarch about what happened next: the so-called Pixodarus affair. Although its chronology and veracity are doubtful, the affair points to a growing distrust of Alexander toward his father. According to Plutarch, Philip, eager to establish a foothold in Asia, had arranged to marry his son Arrhidaeus to the daughter of the Persian satrap Pixodarus. Alexander, wary that this marriage would relegate him to second place, interfered in the negotiations by putting himself forward as a potential husband. The interference ruined his father’s plans, and he meddled in something that was the exclusive prerogative of the king: to broker marriages for members of the dynasty.

Some researchers have suggested that Philip intended to follow a Macedonian custom and arrange the marriage of his last wife (Cleopatra) to his son (Alexander). This would have sent a clear signal that Philip was passing his kingdom to Alexander and may be why Philip had not thought of Alexander as a suitor.

(These historic Greek sites shed fresh light on Alexander the Great’s lost kingdom.)

An unexpected death

Soon after, Philip was assassinated in Aigai while celebrating the wedding of his daughter, also named Cleopatra, to her uncle Alexander of Epirus, brother of Olympias. The assassin, Pausanias, was a member of the king’s guard. Some accounts state he committed the assassination in revenge, feeling spurned by Philip, whom he loved.

What is certain are the consequences of the attack. Alexander was proclaimed king by the army. He eliminated any rivals who could overshadow him, a customary practice to avoid sources of instability. The purge was far-reaching: from Attalus, prominent in Asia, to Amyntas IV, Philip’s nephew who had reigned briefly while still a child, with Philip acting as regent. For her part, Olympias (according to the historian Justin) killed Europa, Cleopatra’s daughter, and then forced Cleopatra to hang herself in front of her little girl’s corpse.

The murky death of Philip of Macedonia

But did Pausanias act alone? Historians Plutarch and Justin suggest that the instigator was Olympias, as revenge for being spurned by Philip when he married Cleopatra. It would have been in Alexander’s interests

to ensure his father didn’t have children with Cleopatra, since they would challenge his claim to the throne. Second-century historian Arrian attributes the plot to the Persians, in a bid to stop Philip’s planned invasion. Other suspects include Demosthenes (leader of the Athenian resistance); certain nobles of Upper Macedonia; or the Macedonian general Antipater. The incident remains a great historical whodunit.

With the way clear and rivals purged, Alexander ascended the throne. It’s hard to gauge how close father and son had truly been but Alexander’s achievements and rise to greatness should be seen in the context of his relationship with Philip.

(After Alexander the Great’s death, this Indian empire filled the vacuum.)

Alexander's love-hate relationship

This speech contrasts with the episode some years earlier, when Alexander killed one of his generals, Cleitus the Black, during a banquet. According to first-century Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus, Alexander drunkenly boasted that the victory at the Battle of Chaeronea was down to him, but his father had jealously detracted from his glory. Alexander claimed that Philip, wounded on the battlefield, had feigned death and that he had shielded his father’s body from attack. Incensed at this slur on the honor of Philip, Cleitus angrily challenged Alexander, who took up a lance and ran him through.