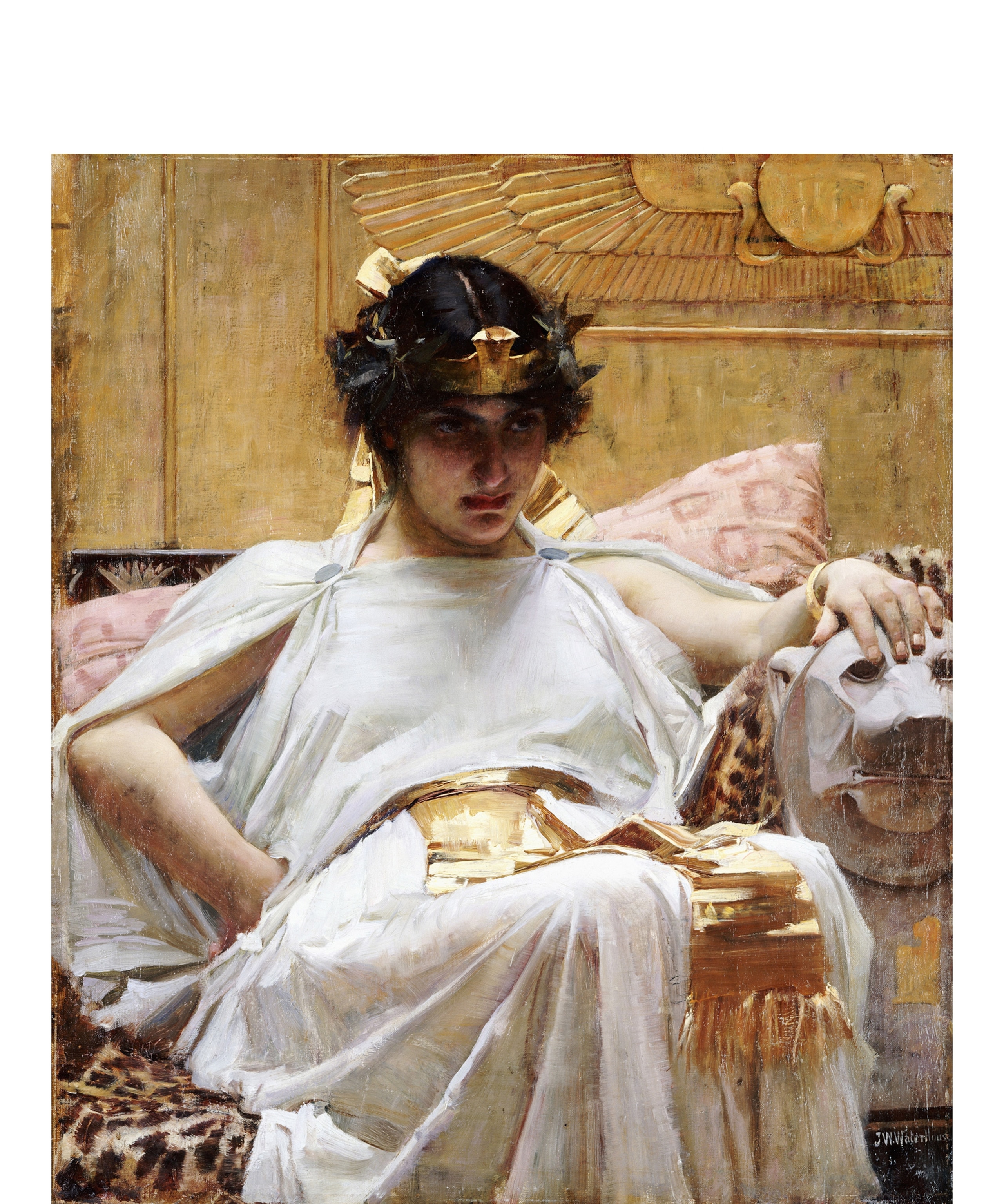

Who was the real Cleopatra?

History paints Cleopatra as a seductress. But there’s little we actually know about Egypt’s politically savvy last queen.

Was Cleopatra beautiful? Debatable. Was she charming? Probably. Was she politically astute and bent on using both her gender and her outsized power to further her needs? Certainly.

Perhaps no historical figure has so enflamed passions—and debates—than Cleopatra VII. Destined to be the last of her dynasty, the Egyptian pharaoh used seduction and political savvy to further the interests of ancient Egypt in the face of the expansion of the Roman republic.

But though she is one of the best-known women in history, there’s little that historians and archaeologists can say for sure about Cleopatra. Here’s what is known about the legendary, yet mysterious, queen of Egypt.

Who was Cleopatra?

Born to Egyptian king Ptolemy XII Auletes and an unknown mother in 69 B.C., Cleopatra was a descendant of the ancient Greek Ptolemaic dynasty that had taken over Egypt in 305 B.C.

(Should women rule the world? The queens of ancient Egypt say yes.)

Though the Ptolemaic Kingdom had adopted some Egyptian religious traditions, it ruled from the largely Greek city of Alexandria. As a result, she grew up speaking Koine Greek, though she was reportedly the only one of her lineage to also learn Egyptian.

Her life would be inextricably bound to unrest in Egypt—and the politics of the Roman Empire through two of Rome’s greatest leaders, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony.

How Cleopatra became queen of Egypt

When her father died in 51 B.C. Cleopatra, then 18, was plunged into a controversy over which of Ptolemy XII’s children should rule Egypt. At first, she ruled jointly with her brother Ptolemy XIII, even marrying him in a nod to Egyptian tradition.

But the young king wanted the throne for himself, and civil war soon broke out as they formed factions to help them gain full power. In response, Cleopatra was briefly forced to flee to Roman-controlled Syria.

(Cleopatra IS brat? These 5 women in history were the OG brat girls)

Her father had been sympathetic to—and reliant on—Rome during his rule. The warring siblings were no different, and they quickly aligned themselves with different sides in Rome’s own brewing civil war.

From her exile in Syria, Cleopatra turned to Julius Caesar, then a general and politician intent on becoming Rome’s sole dictator, for help regaining her throne.

Cleopatra and Julius Caesar

Despite a dramatic age difference—Caesar was 52 when he met Cleopatra, about 30 years older—and the fact that he was married, they began a romantic relationship, and he pledged his support for her.

In 47 B.C., while fleeing Caesar’s troops, Ptolemy XIII drowned in the Nile River near Alexandria. With Egypt in the hands of Caesar, Cleopatra took back the throne as her own, swiftly married her 12-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIV, and declared him her co-ruler. She gave birth to a child her contemporaries assumed to be Caesar’s son, whom she named Caesarion. (No, this is not the origin of the term “cesarean section.”)

(Will the real Julius Caesar please stand up?)

Cleopatra and Caesar’s relationship lasted until his murder on the Ides of March in 44 B.C., at the hands of his enemies in the Roman Senate.

Cleopatra had been on an extended visit to Rome at the time of Caesar’s murder and briefly remained there in the hopes of convincing the Romans to recognize Caesarion as the rightful heir of Roman power.

Soon, however, she returned to Egypt, where historians believe she ordered her brother’s assassination by poison before taking up her throne once more alongside her son Caesarion.

(Meet the only woman privy to the plot to kill Julius Caesar)

Antony and Cleopatra

Caesar was dead, but Cleopatra’s relationship with Rome was far from over. Roman general Mark Antony—who had ascended to power as one of Rome’s three joint leaders, or triumvirs—demanded a meeting with Cleopatra in an effort to continue the Egyptian-Roman alliance.

Eager to maintain Egypt’s close relationship with Rome, Cleopatra traveled to Tarsus in modern-day Turkey to meet him in 41 B.C. Scholars believe she arrived in Tarsus in high style on a sumptuous barge.

“Cleopatra invested her ocean excursions with carefully chosen costumes, divine associations, expensive textiles and jewels, music, and exotic essences,” wrote art historian Diana E. E. Kleiner in her book Cleopatra and Rome.

The pharaoh meant to impress, and it worked. Almost immediately, she began a torrid love affair with the married Antony, who moved to Alexandria to be with her.

(Inside the decadent love affair of Cleopatra and Mark Antony.)

How Cleopatra died

But Antony’s infatuation with Cleopatra—and the reputed excesses of their life in the Egyptian seat of power—led to both their downfalls. The Roman ruler plunged into outright war with his co-triumvirs and his own people, who resented what they saw as Egypt’s influence in Roman affairs.

After Mark Antony’s defeat in the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C., the Egyptian queen barricaded herself in her royal mausoleum and told him she planned to kill herself. In response, Antony stabbed himself, eventually dying in her arms.

Cleopatra attempted to negotiate with Octavian, her lover’s former co-ruler. But when she realized he intended to take her captive and parade her in the streets as a prize, she again barricaded herself in her tomb with some servants and killed herself, likely with poison. The rule of her dynasty was over, and Egypt was taken over by Rome.

What we don’t know about Cleopatra

Legend has it that Cleopatra took her life with the help of a poisonous viper called an asp, but there is no proof. Nor have archaeologists ever found the mausoleum where she, and likely Antony, died. As Chip Brown wrote for National Geographic’s July 2011 issue, “Most of the glory that was ancient Alexandria now lies about 20 feet underwater.”

However, history hunters, such as lawyer-turned-archaeologist Kathleen Martinez, continue to search for her tomb. Martinez’s years-long effort is documented in Cleopatra’s Final Secret, premiering September 25 at 10/9c on National Geographic and streaming the next day on Disney+ and Hulu. (Check local listings.)

(Explore the elaborate tomb of Nefertari—and see how ancient Egyptians buried their royals)

There’s also no way to gauge the accuracy of historical portrayals of the queen, which are deeply contradictory and show the biases of their time. Some extant coins show Cleopatra as a plain-looking woman, while others depict a mirror image of Antony, reflecting their makers’ opinions about the female ruler’s liaison with her Roman lover.

Debates also still rage about Cleopatra’s race, although historians point out that not only do we not know for sure but our entire concept of race didn’t exist in Cleopatra’s time.

Written sources about Cleopatra are also scant. The library of Alexandria was destroyed multiple times, taking contemporary accounts of Cleopatra with it.

According to the ancient chronicler Plutarch, whose biography of Antony is one of the most detailed accounts of Cleopatra’s reign, she was a woman of “the most brilliant beauty and … at the acme of intellectual power.”

But he wrote about the Egyptian queen hundreds of years after her death in August, 30 B.C.—and brought a decidedly Roman viewpoint to his work on the queen.

(Searching for the true face—and the burial place—of Cleopatra.)

Despite our lack of understanding of Cleopatra’s life, she remains relevant today. From Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra to television shows, she has gained a nearly legendary reputation as a wily politician with an almost superhuman ability to seduce.

Though the former was almost certainly true, we may never know why some of the world’s most powerful men succumbed to Cleopatra’s charms.

What is certain is that, Cleopatra was a woman who so cannily ruled men—and her people—that she’s managed to enchant and mystify people more than 2,000 years after her death.