America’s last slave ship is more intact than anyone thought

Archaeologists studying the Clotilda, which was identified in 2019, say the shipwreck may contain a wealth of well-preserved artifacts, from barrels of food to human DNA.

When the 160-year-old wreckage of the Clotilda, America’s last known slave ship, was positively identified in the murky waters of the Mobile River in 2019, that was enough for Joycelyn Davis.

Growing up in historic Africatown near Mobile, Alabama, Davis always believed the stories she heard about the origin of her community: That a wealthy white businessman made a bet that he could import enslaved Africans into Mobile, long after the practice had been outlawed. That the Clotilda’s captain, William Foster, returned from Africa in 1860 with 108 captives on board—including Charlie Lewis, Davis’s ancestor and one of the founders of Africatown. That Foster had tried to destroy the evidence of his crime by burning and scuttling the Clotilda. And that somewhere out there in the Mobile River lay the remains of the vessel.

“The ship in itself doesn't make it real for me,” Davis says. “Just knowing my ancestors were documented, the books that were written ... those were enough for me. But the ship was icing on the cake.”

Now, archaeologists have come up with more revelations that make the already exceptional Clotilda rarer still.

Since the Clotilda’s identification, researchers have been studying the shipwreck and the history surrounding it. Their efforts have resulted in the vessel being named to the National Register of Historic Places. They’ve also revealed that much more of the ship has survived than was first thought, making the Clotilda not only the last American slave ship, but also the best preserved.

“This is the most intact slave ship known to exist in the archeological record anywhere,” says Jim Delgado, a maritime archaeologist who leads research on the Clotilda for SEARCH, Inc. Delgado estimates that up to two-thirds of the ship’s wooden structure has survived, including bulkheads and other modifications that turned the trading schooner into a slaver.

“There’s actual direct physical evidence not just of the ship and its use, but also of the changes done by Foster and his crew to make it a slave ship,” Delgado says. “We can say what the size is of the area where people were held, and that was a very sobering and emotionally powerful moment for the team to see.”

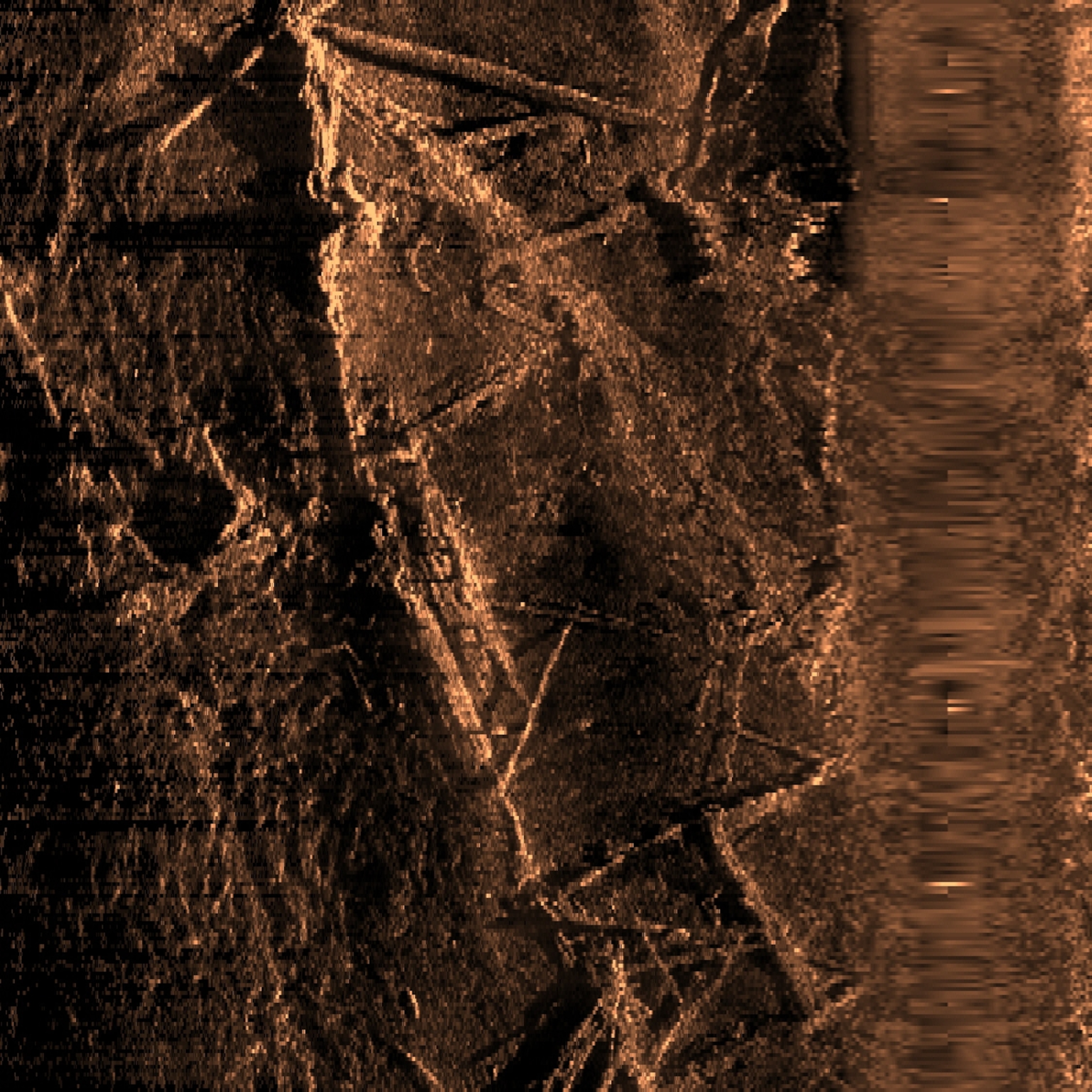

Getting a clear view of the shipwreck in the muddy river is all but impossible, so researchers have relied on sonar to peer through the murk.

“We’re talking about a wreck that sits in a river where visibility for a diver is measured by a couple of inches,” Delgado says. “Sonar has turned the lights on for us.”

Researchers have also gained new insight into the ebb and flow of silt covering portions of the shipwreck.

“We now know the mud that’s on the site does move. Sometimes it comes off, sometimes it goes on,” Delgado says, likening the movement to a tide coming in and out. “Sometimes, things are exposed that haven’t previously been exposed then get covered again.”

A “limited and targeted” excavation of the wreck is planned for March, Delgado says. Supplies that were likely stored in the vessel—including barrels of water, pork, beef, rice, rum, molasses, flour, and bread—may still lie buried in the ship’s hold. There’s even the possibility of recovering human DNA from traces of bodily fluids or excrement between the ship’s planking.

“Those types of things may very well be in there,” Delgado says, adding that the potential for future discoveries helped make the case for the National Register listing.

The upcoming excavation will include taking wood samples, examining the aquatic species colonizing the wreck, and determining what can be done to offset deterioration of the site. The information will be used to determine what should come next for the Clotilda, including whether or not its remains can be raised.

Stacye Hathorn, State Archaeologist with the Alabama Historical Commission, is doubtful.

“One of the problems you have is that as you excavate something, you destroy context, and context tells the story,” Hathorn says. “You have to be very careful to gather all the information you can, because you only have one shot at it. You don't preserve things by destroying them.”

A better option may be to preserve the shipwreck in place and construct a memorial nearby, similar to what was done with the U.S.S. Arizona in Pearl Harbor. In any case, archaeologists and state officials will work closely with the Clotilda’s descendant community in determining the best course. A new museum, Africatown’s Heritage House, is expected to open next summer.

For Davis, any detail uncovered by researchers feels like a small miracle, each one an opportunity for her community's story to be told on an international stage.

“It's amazing,” she says. “You could not have told me 10 or 15 years ago all of this would unfold, because it was a myth—but everything was documented.”