This Roman emperor had a decadent grotto by the sea. Here's what was inside.

In 1957, the first fragments of statues were discovered at Sperlonga, Emperor Tiberius's pleasure palace from the first century A.D. But when Italian officials tried to take the relics to Rome, the locals fought back.

Steeped in wealth and opulence, Roman rulers had many private luxuries. During the first part of his reign, Emperor Tiberius (r. A.D. 14–37) extended a pleasure palace at Sperlonga, on the coast midway between Rome and Naples. Set back from the beach, the original villa was magnificent enough. But what really dazzled guests was the feature at the center of the complex: a vast grotto that opened onto the Mediterranean.

Tiberius had the floor of the grotto turned into a circular pool. Sculptural groups, based on the life of the hero Ulysses, adorned the cave’s interior—some placed on a platform in the water, others in galleries in the rock face.

Beyond the grotto’s mouth, Tiberius had an open-air rectangular pool carved into the beach. In the middle of this pool was an islet on which the emperor would hold banquets for his friends.

The discovery

In A.D. 26 part of the grotto collapsed. Second-century historian Suetonius recounts that as Tiberius “was dining near Terracina in a villa called the Grotto, many huge rocks fell from the ceiling and crushed a number of the guests and servants, while the emperor himself had a narrow escape.” Tiberius was saved by his confidant Sejanus, a prefect of the Praetorian Guard, who used his body to shield the emperor. After the accident, Tiberius left the villa and moved to Capri. But the villa was in use until the eighth century, after which it fell into disuse and was repurposed as a nymphaeum.

(See the summer solstice from a Roman emperor’s party cave)

A famous cave

As the centuries passed, stories emerged of people finding the remains of sculptures in “Tiberius’s grotto.” But it was not until the middle of the 20th century that formal archaeological excavations were carried out.

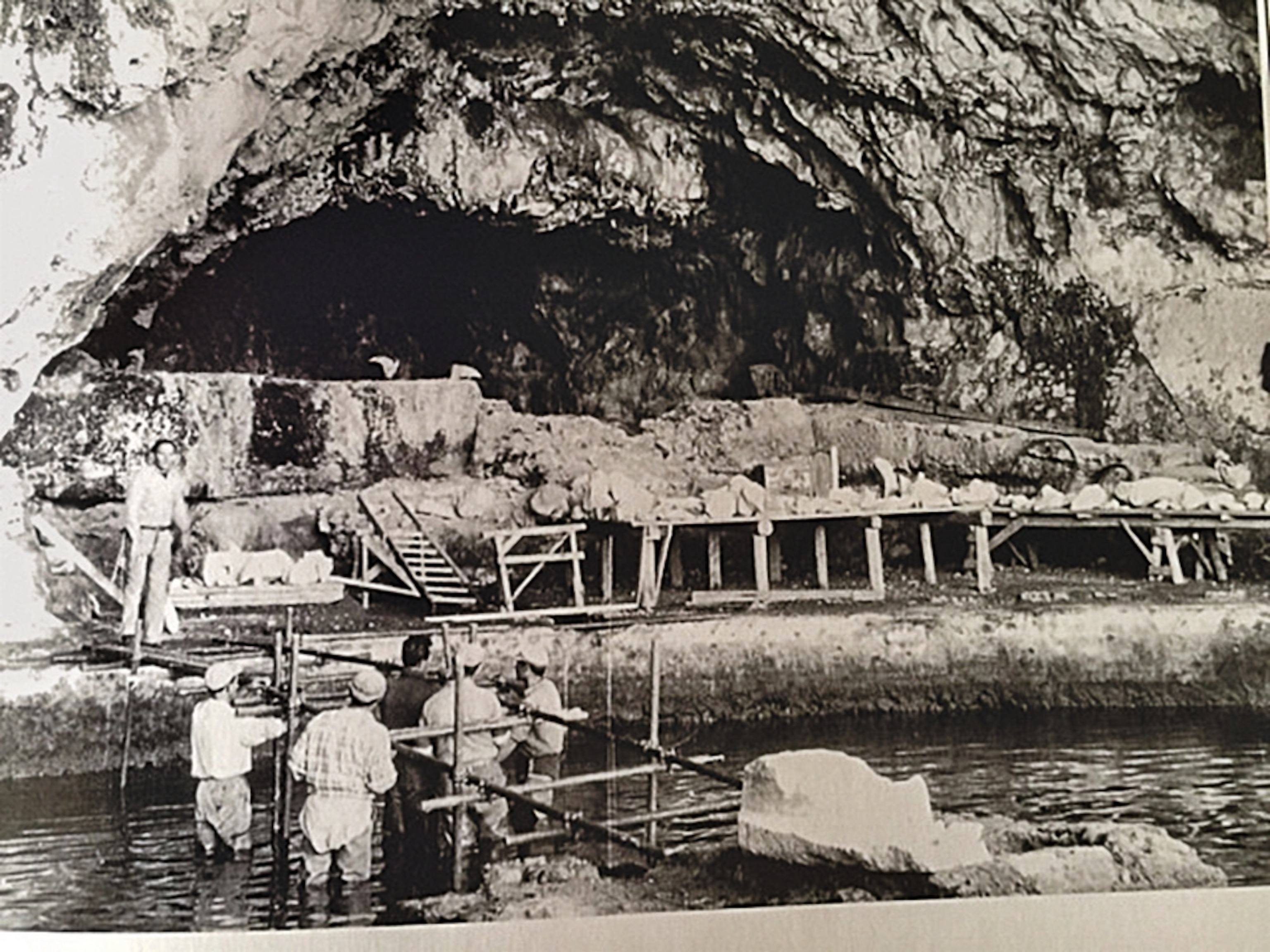

In 1957 construction work began on a highway to link the cities of Terracina and Gaeta. The route would pass close to Sperlonga, so the government commissioned archaeologist Giulio Iacopi to carry out an investigation of the cave. During an initial inspection on August 23, Iacopi noted the cave contained fragments of ancient sculptures.

ULYSSES AND POLYPHEMUS

CONFRONTING SCYLLA

A few days later, Iacopi received a visit from the director of the roadwork, engineer Erno Bellante. Bellante told him he was passionate about archaeology and offered to help in the research by whatever means he could. Iacopi assigned him some sites near the new road, but this was not enough for the archaeology-loving engineer. Familiar with what the classical sources said about the presence of Emperor Tiberius in Sperlonga, and without informing Iacopi, Bellante began excavating the cave. The marble fragments he found clearly belonged to Roman sculptural groups.

Under a layer of earth and sand, in the center of the grotto, he found evidence of a structure. A week later—without consulting Iacopi—Bellante informed the archaeological authorities of his findings. When Iacopi heard the news, he was furi- ous at what he considered the intrusion of “an unauthorized excavator” and quickly took back control of the project.

The fragments unearthed by Bellante suggested that the artifacts hidden in the cave would be highly significant, but Iacopi made errors of interpretation. One piece of marble bore an inscription mentioning the Greek sculptor Agesander. Iacopi seized on this and claimed that among the Sperlonga statues was nothing less than the original of the Laocoön sculptural group, made famous by the copy discovered in Rome in 1506. Iacopi’s hypothesis would soon be disproved.

More trouble was in store for Iacopi: When he attempted to take the statue fragments to Rome, the people of Sperlonga united to prevent what they considered to be a heist. One newspaper described how residents of Sperlonga threw balls of mud at the workers who had come to collect the artifacts.

(8 things people get wrong about ancient Rome)

An arduous task

In the end, the Italian authorities decided that the finds would remain in Sperlonga. Once all the fragments, some 6,000 in total, had been collected, restoration work began to reconstruct the statues and ascertain their original state. This momentous task was carried out by archaeologist Baldassare Conticello and sculptor Vittorio Moriello. Following much painstaking work, they pieced together, at least in part, four sculptural groups that decorated the grotto in the time of Tiberius. The locals of Sperlonga, suspicious of interference from Rome, ultimately got their wish: Since 1963 the restored groups have been on display in the National Archaeological Museum of Sperlonga, alongside Tiberius’s beachside grotto.