What happened to the Ark of the Covenant? Here’s what we know.

Traditional sources and scholars have long hypothesized the location of this sacred chest. But tracing its whereabouts is more difficult than it seems.

In A.D. 70, after a brutal, months-long siege, Roman troops under General Titus stormed Jerusalem to crush a Jewish revolt against imperial rule. The city fell, and the Second Temple—the spiritual heart of Judaism—was plundered and burned. Roman soldiers seized its sacred treasures. However, one crucial artifact was noticeably missing: The Ark of the Covenant. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, an eyewitness to the events, wrote an account a few years later in The Jewish War, detailing the temple’s destruction and the triumphal parade in Rome that followed:

“The golden table, of the weight of many talents; the candlestick also, that was made of gold... and the last of all the spoils, was carried the Law of the Jews.’’ Amongst all the treasures, there is no mention of the ark, in which the Tablets of the Law should have been housed. The ark hadn’t been destroyed in the siege. It had vanished centuries earlier.

Origins of the ark

The story of the ark is difficult to pin down, mainly because sources provide differing accounts. Some scholars have raised the possibility that more than one ark may have existed—perhaps built at different times, or even used simultaneously—leaving open the question of which, if any, was the original. The Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) describes the ark’s origins at length. After the Israelites fled Egypt during the Exodus in the 13th century B.C., they made camp at Sinai, described as a wild region located outside of Egypt. They stayed there for two years, receiving divine law and guidance for their future as a nation. Yahweh (God) gave Moses the Tablets of the Law, on which he had inscribed his ten commandments. Yahweh ordered Moses to keep them in a chest made of wood and gold, with five main features. The chest was to be made of acacia wood, 2.5 x 1.5 x 1.5 cubits (3.75 x 2.25 x 2.25 feet) in size, with gold overlay inside and out.

Four rings were to be attached to the bottom of each corner, through which carrying poles made out of acacia wood would be inserted, also in gold overlay. Finally, the Israelites were to place inside it the tablets of the law, a pot of manna, and the rod of Moses’ brother Aaron, which is said to have had miraculous powers.

A home for the ark

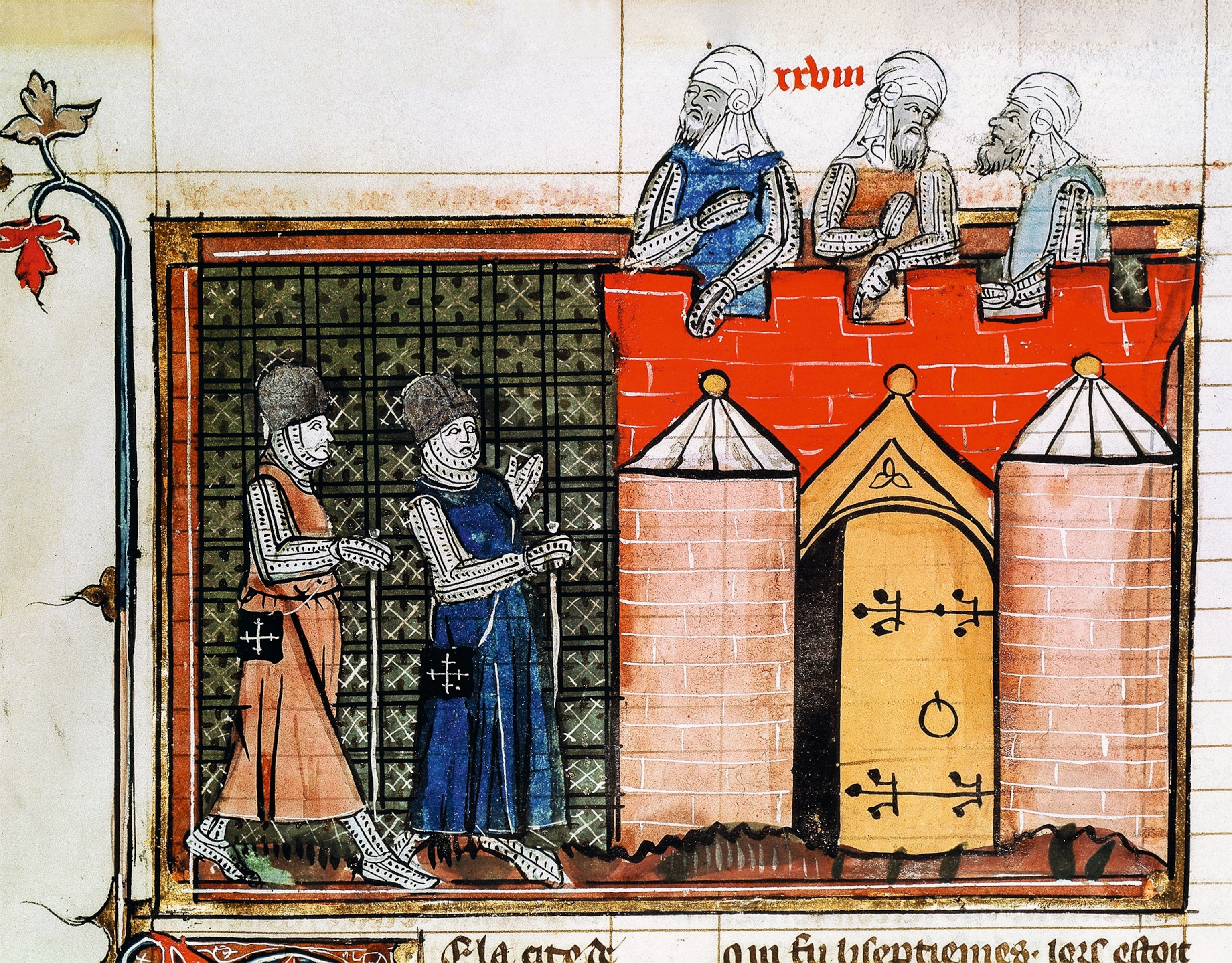

Having fled Egypt, the Israelites enter the wilderness where they will remain for about 40 years. When they reach the sacred Mount Sinai, Moses, their leader, is summoned to the top by Yahweh, who appears wrapped in dense cloud and gives Moses the Tablets of the Law inscribed with the Ten Commandments. Yahweh also provides instructions on how the Israelites should offer sacrifices to him. (Top left)

II - CONSTRUCTING THE ARK

After coming down from Mount Sinai, Moses carries out Yahweh’s orders to build an ark to house the Tablets of the Law: “Have them make an ark of acacia wood—two and a half cubits long, a cubit and a half wide, and a cubit and a half high. Overlay it with pure gold, both inside and out, and make a gold molding around it” (Exodus 25:10). (Top right)

III - THE TABERNACLE

Yahweh also commands Moses to cover the ark with a tabernacle—a kind of tent—made with curtains of blue, purple, and scarlet linen. The book of Exodus mentions various other items that should be made to accompany the ark. These include a lampstand (menorah) of pure gold and paraphernalia required for making offerings. This miniature depicts Moses placing the tablets inside and Aaron placing his rod. (Bottom left)

IV - BURNT OFFERINGS

The Israelites perform the first sacrifice or burnt offering after receiving the Tablets of the Law. They are obeying the following command given by Yahweh: “Bring the bull to the front of the tent of meeting, and Aaron and his sons shall lay their hands on its head. Slaughter it in the Lord’s presence at the entrance to the tent of meeting” (Exodus 29:10-11). (Bottom right)

The Israelites brought centuries of exposure to Egyptian culture to the builiding of the ark. The ark’s design is steeped in the ritualistic style of the Late Bronze Age (c.1550- 1200 B.C.), particularly the boatlike chests used in Egyptian religious festivals to carry images of the gods. The ark’s construction also evokes the gold-covered wooden shrines found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. The cherubs atop the ark, winged guardians, bear a striking resemblance to figures in Egyptian and Near Eastern art. On Tutankhamun’s quartzite sarcophagus, for instance, goddesses with outstretched wings are carved at each corner, shielding the pharaoh in death. Yet the inclusion of these cherubs raises a theological tension: it appears to contradict the commandment, “You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below” (Exodus 20:4).

The presence of Yahweh

While the Israelites were still wandering in the wilderness, Yahweh manifested himself in a pillar of cloud by day and fire by night, leading them onward. With the ark, his presence was believed to dwell on the “mercy seat” between the cherubs, offering a constant reminder of the covenant. After the destruction of the Temple by the Romans in A.D. 70, the teachers of Jewish law developed the concept of Shechinah to mean the “presence of God” (literally “dwelling”). Shechinah did not refer to the physical presence of Yahweh, but rather to an unmistakable sign of his nearness. In time, even without the ark or Temple, that presence was said to remain.

This contradiction between the commandment forbidding the making of graven images and the inclusion of golden cherubs atop the Ark of the Covenant has long puzzled scholars. To resolve this, many biblical scholars and theologians have pointed to the context and purpose of the cherubs. They were not idols meant for worship but symbolic guardians of the divine presence, placed atop the ark in the innermost sanctuary where no ordinary worshipper could see or access them. Their role was not representational but theological: they framed the “mercy seat,” the space where God’s presence was said to dwell. The cherubs were divinely sanctioned and functioned more like ritual art than forbidden images, underscoring the unique and controlled nature of Israelite worship. The Ark of the Covenant became central to Israelite religious life, and during the 40 years they spent wandering in the desert following their escape from Egypt, the ark was always carried ahead of them. The Israelites believed that the ark and its precious contents had the power to protect them and punish their enemies.

The journey

Joshua succeeded Moses after his death and ultimately led his people to Canaan, the Promised Land. According to the Book of Joshua, when they reached the Jordan River it was flooded. Following God’s command, the priests carrying the ark stepped on the water, and it miraculously stopped flowing, allowing the Israelites to cross on dry ground. When they faced their first military challenge, capturing the Canaanite stronghold city of Jericho, their ark-led march around the city caused its walls to collapse. The ark had an aura of immense, even dangerous, power. It was said that looking inside or touching it could lead to death.

After several conquests, the Israelites finally settled in Canaan and established the city of Shiloh as their religious center. There, they set up the Tabernacle (a portable tent), placing the sacred chest in its innermost chamber, its first permanent sanctuary. But when they went to battle against the Philistines at Ebenezer, in 1116 B.C., the Israelites brought it to the front lines for protection—only to lose both the battle and the ark itself. The Philistines captured it and took it through the cities of Ashdod, Gath, and Ekron, but wherever it went, plagues followed. Convinced they had angered the Israelite god, the Philistines returned the ark.

Later, King David (r.1000–962 B.C.),second king of a unified Israel, brought the ark to his new capital, Jerusalem, where it was also housed in a tent sanctuary. His son, Solomon, finally gave it a permanent home, the Temple on Mount Moriah. There, in the Holy of Holies, the sacred chest rested—hidden from view, accessed only once a year—and only by the high priest.

The ark’s whereabouts

The Book of Chronicles refers to the ark’s likely presence in the Temple in the time of King Josiah of Judah, who lived in the second half of the seventh century B.C.: “He said to the Levites, who instructed all Israel and who had been consecrated to the Lord: ‘Put the sacred ark in the temple that Solomon son of David king of Israel built. It is not to be carried about on your shoulders.’”(2 Chronicles 35:3).The passage does not clarify the ark’s location before the order was given to restore it to the Temple.

The trail shifts to Ethiopia

When the Queen of Sheba visited Solomon, they conceived a son, Menelik. On his 22nd birthday, Menelik went back to Israel to meet his father. Solomon recognized him as his son and heir, which riled the religious elites. Solomon was forced to send his son back to Ethiopia, but, angered by the way Menelik had been received, Solomon ordered all the first-born sons of Israel, some 12,000 males, to accompany Menelik to Ethiopia. According to this legend, it was they who stole the ark and took it with them, telling Menelik that they had the ark only when it was too late to take it back. The ark is said to have remained in Ethiopia, in the Church of St. Mary of Zion, Aksum, where it was said to be accessible only to the monk assigned to take care of it.

Non-biblical sources state that when King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon conquered Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple in 586 B.C. there is no mention of him finding the ark. The sacred chest was likewise missing from accounts of Titus’s destruction of the Temple six centuries later. The Bible does not make explicit when, or how, the ark disappeared from the temple. Based on biblical and other accounts, some scholars argue the disappearance took place sometime between the time of Josiah in the late 600s B.C. , and 586 B.C., when the Babylonians captured Jerusalem.

Various explanations emerged regarding the fate that might have befallen the sacred object. Several non-biblical, religious writings account for the fate of the ark. The Talmud, the foundational body of Jewish civil and religious law compiled between the third and sixth centuries A.D., recounts that some years before the Babylonian destruction of the First Temple in 586 B.C., King Josiah foresaw the threat and hid the ark. According to this version, it was buried, along with other sacred artifacts, in a chamber beneath the Temple that Solomon had prepared centuries earlier for such a purpose.

Additional accounts appear in the non- biblical, Christian texts known as the Apocrypha. An apocryphal text based on the Book of Ezra describes scenes of devastation as King Nebuchadnezzar’s forces destroyed the Temple. Among the horrors witnessed, the text claims the Babylonians carried the ark away. If true, this would suggest the chest was taken to Babylon; however, no ancient source confirms this account.

Another story focuses on the early sixth-century B.C. prophet Jeremiah. According to the Second Book of Maccabees (a text recognized as part of the biblical canon by some Christian denominations, but not by others), Jeremiah received a divine revelation warning of Jerusalem’s fall: “The prophet, in virtue of an oracle, ordered that the tent and the ark should accompany him, and... he went to the very mountain that Moses climbed to behold God’s inheritance.” Scholars believe the mountain referred to is Mount Nebo, in what is now Jordan, from whose heights Moses is said to have glimpsed the Promised Land before his death. There, Jeremiah hid the sacred objects in a cave and sealed the entrance. According to that tradition, no one who accompanied him could later find the spot again.

The raiders

Scholars have sometimes speculated on the fate of the ark in biblical and religious texts where there is no explicit reference to the sacred chest. The First Book of Kings, chapter 14, states: “In the fifth year of King Rehoboam, Shishak king of Egypt attacked Jerusalem. He carried off the treasures of the Temple of the Lord and the treasures of the royal palace. He took everything.” Most researchers identify this Shishak of the biblical account with Pharaoh Sheshonq I, founder of the 22nd dynasty, who around 935 B.C.,undertook a military campaign in Palestine.

If Sheshonq I attacked Jerusalem and carried off “the treasures of the temple of the Lord,” the ark might have been among such spoils. However, in this text, Jerusalem is not included in the list of cities subdued during the campaign. All the conquered cities mentioned are, in fact, located in the Negev desert, the area in the south of the kingdom of Judah, close to Egypt but far from Jerusalem.

There is no mention of an object resembling the ark in the Egyptian sources. It could be argued that to the Egyptians, the sacred chest was nothing more than a wooden box covered with gold, and that, accustomed as they were to seeing much more sumptuous objects, they did not pay much attention to it. This, of course, is the theory explored in Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, featuring treasure hunter and archaeology professor Indiana Jones. In the movie, the ark is believed to be in the city of Tanis in the Nile Delta, at a place known as the “Well of Souls,” having been hidden there by Shishak. It is likely that the pharaoh was indeed buried in the royal necropolis at Tanis, although his tomb hasn’t been found; and if it had been, it was probably looted centuries ago.

The ark and the templars

The knights occupied the area near what is today known as the Dome of the Rock. This has fueled numerous legends linking the Templars to the lost Ark of the Covenant. Some stories claim the knights searched the subterranean vaults in vain; others suggest they did, in fact, discover the ark and secretly transported it to England or France. One of the most persistent versions comes from a 1966 book by Louis Charpentier, who argued that a group of Templars, fleeing persecution after the order’s violent suppression in 1312, smuggled the ark to France and hid it beneath the cathedral of Chartres.

Ark hunters have found other passages in the Bible that could refer to the Ark of the Covenant without explicitly naming it. One such account reaches back to before the destruction of Solomon’s First Temple. During the seventh-century B.C. reign of the “wicked” King Manasseh, Judah faced Assyrian aggression again. The Bible’s Second Book of Chronicles describes how Manasseh was captured and taken to Babylon with a hook in his nose and bound in bronze shackles. Though eventually released, he returned to Jerusalem as a vassal, subject to the Assyrian empire. As such, he would have been expected to pay tribute—with regular offerings or gifts—to the Assyrian king. The Bible portrays Manasseh as a ruler who desecrated the Temple and turned away from Yahweh. This has led some to speculate that the gold-covered ark might have been offered up as tribute. Another theory is that the high priests removed the ark from the Temple so that Manasseh could not melt it down.

Mystery on the mount

Modern hypotheses have emerged surrounding the whereabouts of the Ark of the Covenant. One of the most respected theories was put forward by Leen Ritmeyer, a Dutch archaeological architect and expert on the Temple Mount. In 1996, he published an article stating he believed the Holy of Holies was located in the First Temple, arguing that there was a possibility that the ark was still located inside it. The Holy of Holies was only entered once a year by the High Priest, so it was effectively buried from view. This could explain why there is no later reference to the ark in Jewish literature.

Ritmeyer proposes that the Holy of Holies lies beneath a rectangular depression in the floor of the Dome of the Rock, which currently stands on the Temple Mount. The Dome of the Rock is part of the Al Aqsa Mosque complex, revered by Muslims. The theory that the ark is still under the Dome of the Rock is shared by some Orthodox and Conservative Jews who advocate the building of a third temple on the site of the previous two. Because of the centrality of the site to Judaism and Islam, the Temple Mount is a significant regional flashpoint.

For now, the ark remains an enigma, its fate obscured by layers of history, theology, and politics. Each new theory, each new speculation, continues to capture the imagination of believers and nonbelievers alike.