The teen who refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus—before Rosa Parks

Claudette Colvin’s bold stand comes into focus during Black History Month, highlighting young activists who helped shape the fight for civil rights.

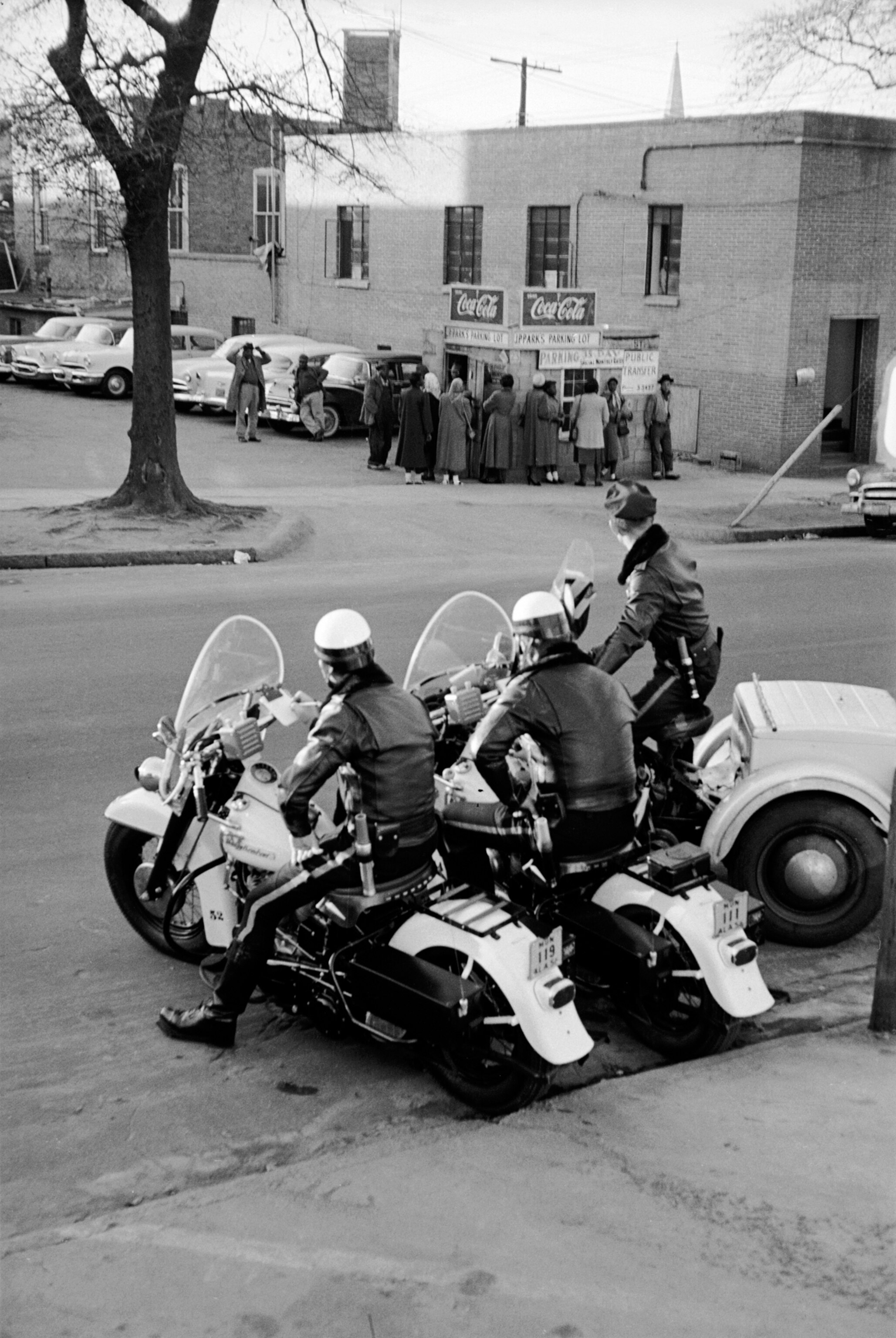

Police boarded the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, handcuffs and batons at the ready. A young Black woman had refused to give up her seat to a white passenger—even when she was told she’d be arrested. Soon, she’d been handcuffed and dragged off the bus, locked in a jail cell and charged with a crime against segregation. Unlike those who came before her, she would refuse to plead guilty in court.

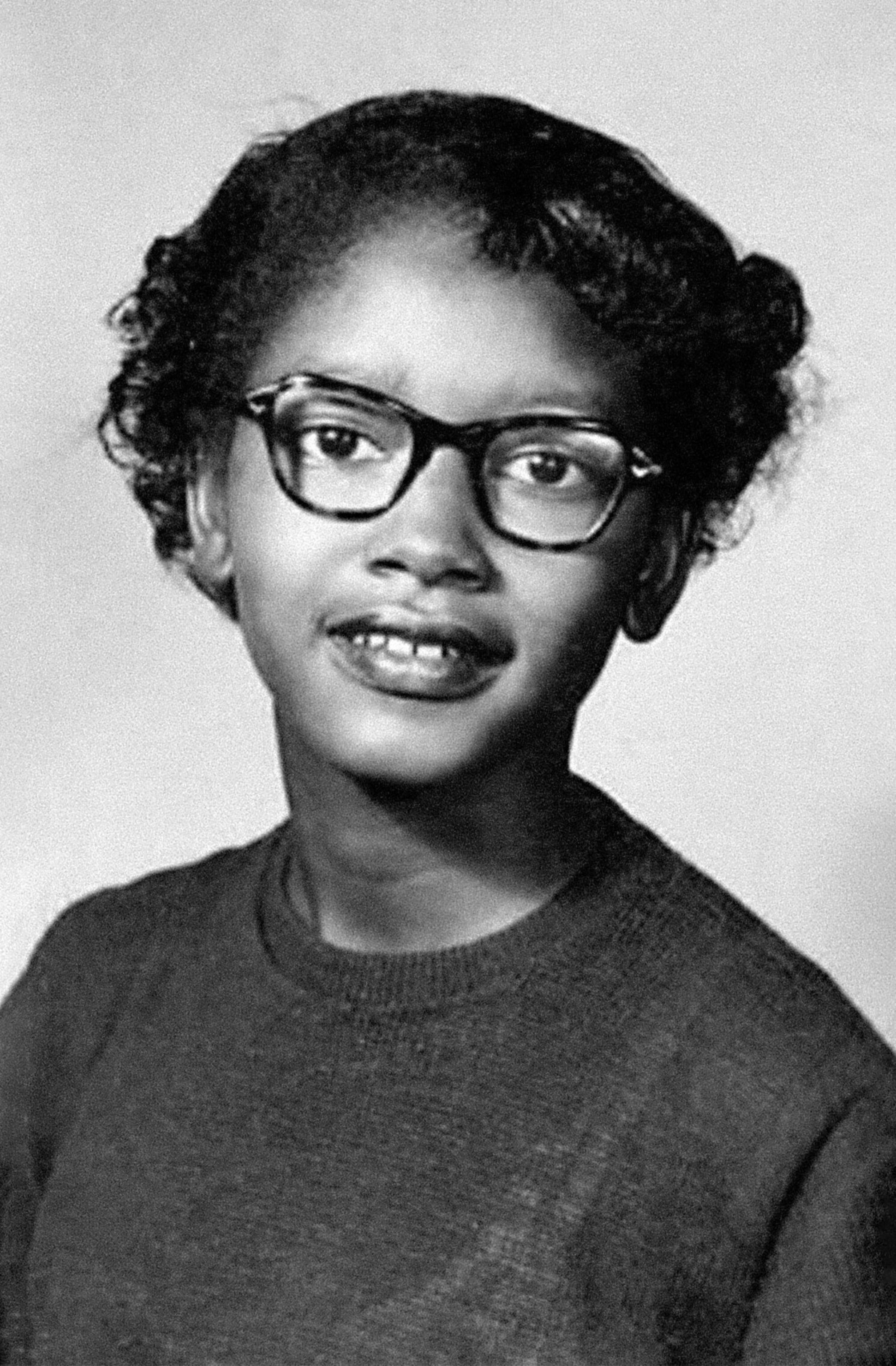

But the woman in question wasn’t Rosa Parks, the civil rights icon whose December 1955 arrest for refusing to give up a bus seat to a white passenger sparked a citywide bus boycott and became pivotal to the broader civil rights movement across the United States. She was 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, and it was March 1955, nine months before Parks’ protest.

Though Colvin’s story is less well-known than that of Parks, her rebellion helped set the stage for the movement. The civil rights pioneer recently died at age 87—but not before her early resistance became better known. Here’s how Colvin fought racial segregation—an act that would ultimately be overshadowed, and downplayed, by other civil rights figures.

Growing up under Jim Crow

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1939, the young Colvin grew up under the care of her great-aunt and great-uncle, who took Colvin in during a time of financial hardship for her single mother. After spending her early years in rural Alabama, she moved to Montgomery with her adoptive parents.

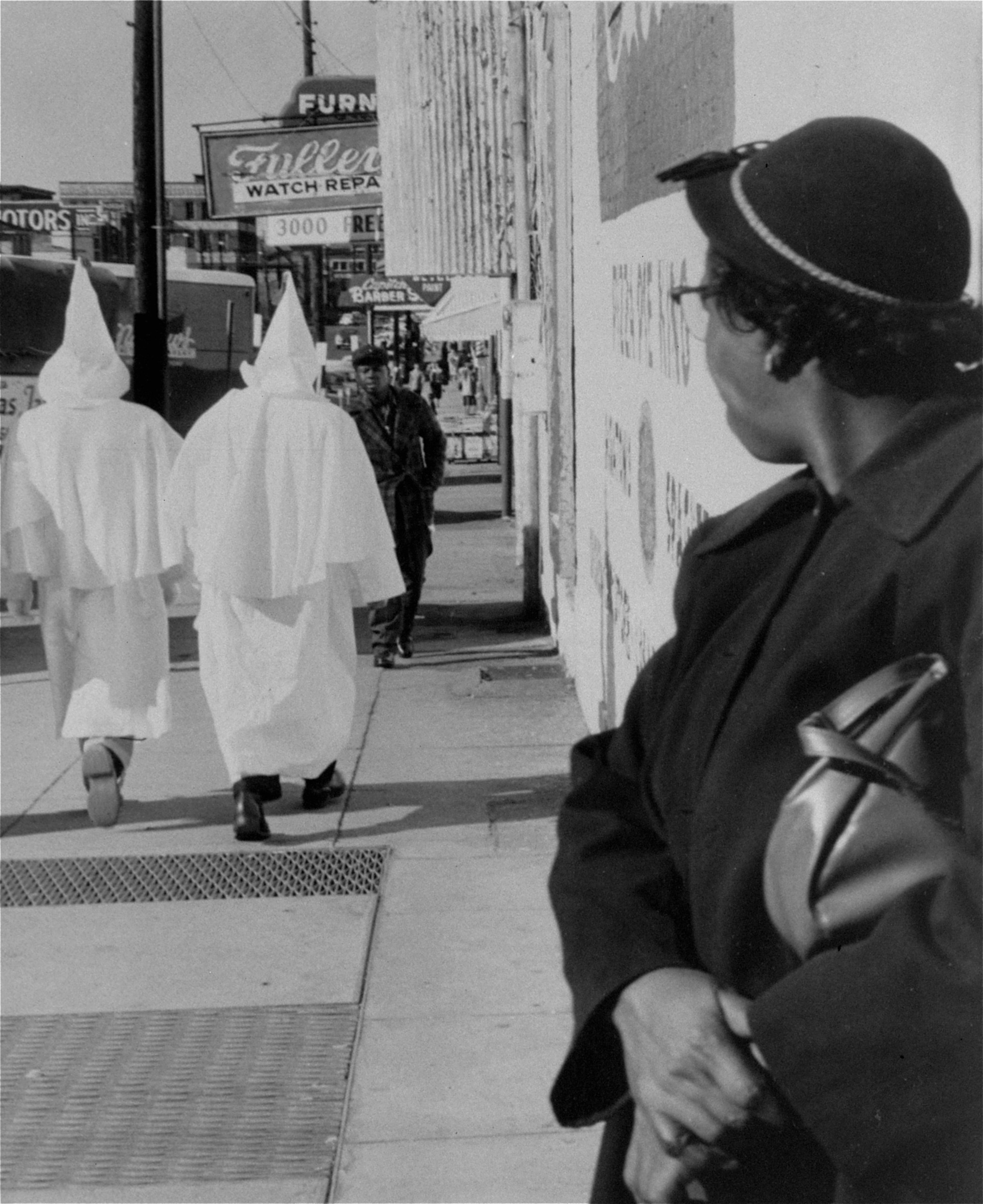

Like other southern cities at the time, Montgomery was ruled by strict Jim Crow segregation laws designed to separate and humiliate its Black citizens. On the city’s busy buses, Black passengers had to navigate a complex web of state and local laws and unspoken racial norms that dictated they could not sit next to, or in front of, white passengers. The bus system’s white drivers strictly, and sometimes brutally, enforced these laws, though Black passengers made up over 70 percent of riders.

(Jim Crow laws created ‘slavery by another name’)

Racism had already left deep impressions on the teenager, who in a 2000 oral history recalled resenting being forbidden to attend a local rodeo or try on shoes at a department store because of the color of her skin. “It bothered me when I got old enough to understand,” Colvin said. Booker T. Washington High School, the segregated school Colvin attended, was one haven, and Colvin was a bright student who enjoyed lessons on Black history and civics.

Claudette Colvin refuses to stand

Those lessons flashed back on March 2, 1955, when a bus driver told Colvin’s entire row to move so a single white person could sit. “It felt as though Harriet Tubman's hands were pushing me down on one shoulder and Sojourner Truth's hands were pushing me down on the other shoulder,” Colvin told the BBC in 2018. The high school junior told the bus driver she had a right to stay seated and refused to move, even after police officers boarded the bus and forcibly ejected her.

Handcuffed and taken to jail, Colvin was charged with violating segregation laws, disturbing the peace, and assaulting a police officer. Those who were charged with similar offenses typically pleaded guilty in court, knowing that all-white juries were virtually guaranteed to find them guilty and that they could face severe repercussions, including physical intimidation and the loss of job opportunities, for resisting. But the outspoken, unapologetic teen decided to plead not guilty. When Colvin was convicted of all three charges, fined, and sentenced, she appealed.

Colvin’s arrest galvanized the local Black community. But not everyone agreed Colvin was the figure the civil rights movement had been looking for. “Some felt she was too young to be the trigger that precipitated the movement,” wrote Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, a pivotal figure in the eventual boycott.

Eventually, youth would become a pivotal part of the civil rights movement. But making early activists like Colvin the face of the movement worried an older generation of Black Southerners who had been taught to remain silent in the face of racial oppression.

Another complication arose when civil rights leaders learned late in 1955 that the teenager had become pregnant out of wedlock. Historian Taylor Branch writes that leaders of the local NAACP and other organizations found Colvin’s personal circumstances and age disqualifying. The strict sexual mores of the time meant Colvin’s pregnancy was seen as unacceptable by people of both races in Montgomery—and potentially destructive to a cause in search of more “respectable” representatives .

"They said they didn't want to use a pregnant teenager because it would be controversial and the people would talk about the pregnancy more than the boycott," Colvin told the BBC’s Taylor-Dior Rumble in 2018.

Education historians Maisha T. Winn and Stephanie S. Franklin write that Colvin was like other Black girls in the juvenile justice system who were “forgotten and abandoned, especially when they have been marked as delinquent, troubled, and undeserving, thus pushing them further from the possibilities of respectability.”

Colvin’s role as a face of resistance against segregation was complicated by another factor too: Though she was fined $10 and given indefinite probation in her case, the judge had dropped the segregation and disturbing the peace charges. This meant her case did not offer a chance to directly oppose Alabama’s segregation laws in court.

And so, when the older, quieter Rosa Parks, a local civil rights leader, refused to give up her seat later that year, Parks and not Colvin became the face of the fight against segregation, sparking the bus boycott that would be pivotal in the struggle.

(How activist Rosa Parks changed the course of history)

Colvin’s federal lawsuit

In 1956, Colvin got another chance as a civil rights pioneer when community leaders asked if she’d be willing to participate in a federal case challenging Alabama’s segregation laws. Colvin agreed to be party to a lawsuit against Montgomery’s mayor, W.A. Gayle, other city and state officials, and the Montgomery bus company. Browder v. Gayle, a case that combined Colvin’s with three others filed by Black women who were mistreated on Alabama buses, went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declared bus segregation unconstitutional on December 17, 1956.

By then, the older Parks had become one of the most recognizable faces of the struggle. Colvin, on the other hand, was rarely mentioned in histories of the civil rights movement.

Colvin lived out the rest of her life in relative obscurity, working 35 years as a nurse’s aide at a New York nursing home. Phillip Hoose’s award-winning book Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice, and a variety of honors and accolades gave her more visibility in her later years, and in 2021, 66 years after the arrest, Colvin’s record was expunged by a Montgomery Juvenile Court judge. She died in January 2026.

Would Colvin have still resisted had she known she’d be overshadowed by other key players in the movement? In interviews taken throughout her lifetime, she never wavered on that question. “I’m not sorry I did it,” Colvin recalled in 2000. “I’m glad I did it. My generation was angry. And people just wanted a change.”