How Racism, Arrogance, and Incompetence Led to Pearl Harbor

The Japanese surprise attack should not have been such a surprise.

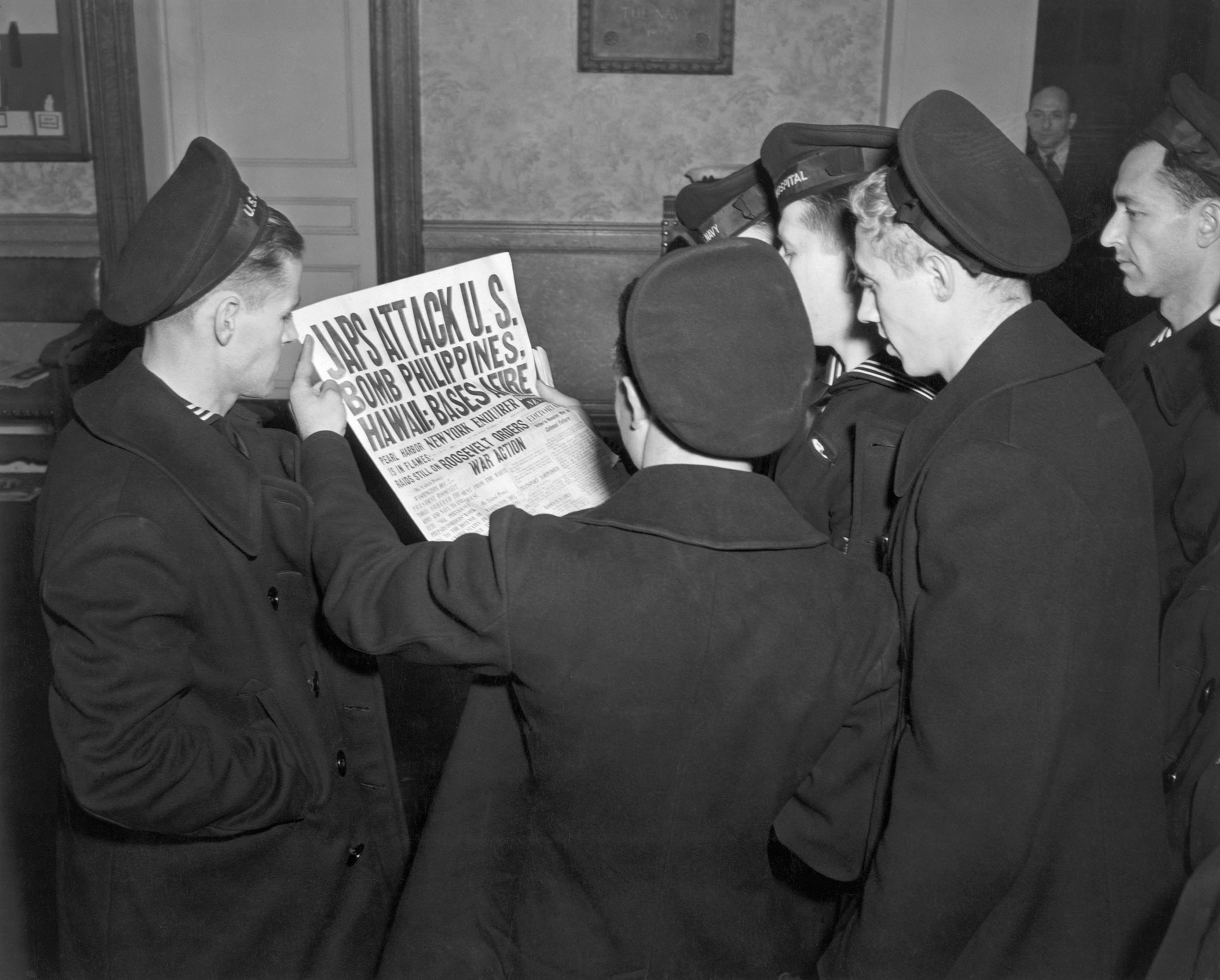

Seventy-five years ago, at 7:55 a.m. on December 7, 1941, a Japanese strike force unleashed 353 warplanes on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s base on Oahu, Hawaii. Relations between the United States and Japan had been worsening—Japan had invaded China in 1937 and then, in 1940, allied itself with Italy and Germany—but the attack was a shock.

Within minutes, much of the Pacific Fleet had been destroyed, more than 2,000 Americans killed, and the United States dealt a massive psychological blow. “Nothing as catastrophically unexpected, as self-image shattering, had happened to the nation in its 165 years,” writes Steve Twomey in his new book, Countdown to Pearl Harbor: The Twelve Days to the Attack. What's worse, it could easily have been prevented. (Find out how five people survived the atomic blast at Nagasaki at the end of World War II.)

Speaking from his home in Montclair, New Jersey, Twomey explains how notions of racial superiority made the Americans underestimate the Japanese, how a war game simulation of such an attack had been run and then ignored, and why Pearl Harbor stunned the nation even more than 9/11.

A preventable catastrophe, caused by incompetent leadership, racist stereotypes, and an arrogant belief in the invincibility of the United States—is that a fair assessment of Pearl Harbor?

That’s extremely fair. I use the phrase “Assumption fathered defeat,” and it did on many levels, both big and small. All through 1941, there were newspaper articles touting the superiority of the [United States] Navy. There was also an assumption in Washington that the Pacific Fleet had been alerted and was ready, which wasn’t the case. It goes all the way up to the racial assumptions about the potential ability of the adversary. From big things to small things, America was complacent about where things stood on December 7.

If you read the American magazines and newspapers in 1941, it’s amazing how the Japanese were considered a funny, curious people, who were technologically inept. They were supposedly physiologically incapable of being good aviators because they lacked a sense of balance and their eyes were not right. It was even believed that the Japanese were bad pilots because, as babies, they would be carried on the backs of their big sisters and got bounced around, so their inner ear was knocked askew. [Laughs]

But the most important mistake was that the American Pacific Fleet commander, Husband Kimmel, all through these days when he knew things were getting more tense, chose not to begin air reconnaissance, which was the sole means by which he could make sure that he was safe.

However, if you are going to pin the label of incompetent leadership on anyone, it should go to Harold Stark, chief of naval operations in Washington. There were clues coming in that he should have read more accurately. Several days before the attack, the Japanese had ordered the burning of all documents at Japanese embassies. And on December 6, a coded Japanese message showing that an attack was imminent was intercepted. But the message Stark wrote to warn the forces out in Hawaii was ambiguous in its warning and could be misunderstood—and it was.

Put us on the sea on the morning of the attack. It must have been carnage.

The best way to describe it is to talk about Husband Kimmel. It was a Sunday morning and he was about to play golf with the commander of the Army on Oahu. He had a large house that sat on a rise overlooking the harbor, and he was there when he was told in a series of phone calls that an air attack was underway.

He walked out into the yard and looked down on the harbor as Japanese planes swarmed above his ships. It was the most stunning moment of his life. He realized immediately that this was catastrophic.

The aviators were some of Japan’s finest pilots and, in contrast to all the press and publicity of 1941, they were very good. The greatest damage was caused by 40 Japanese torpedo planes. That was shocking because the Americans thought Pearl Harbor was too shallow to drop torpedoes. The Japanese had solved that problem by attaching extra fins to the torpedoes, so they didn’t dive too deeply.

The single most devastating explosion came when a bomb plunged into the forward magazine of the battleship Arizona. The ship all but disappeared in a purple cloud of smoke that rose a thousand feet into the air. Most of the people killed on December 7 were killed in that explosion. In all, there were about 2,400 fatalities, and 17 or 18 ships out of about a hundred warships in the Pacific Fleet were destroyed.

It’s important to note that, militarily, the attack was less horrific than people think. It was more a psychic strike on America. There were no American aircraft carriers in the harbor at that time. One was on the West Coast and two were at sea.

Six months later, one of those two [at sea] was essential to the greatest American victory of the Pacific war when the American fleet surprised and ambushed the Japanese, sinking four of the six aircraft carriers that had participated in Pearl Harbor.

One of the battleships damaged at Pearl Harbor also ended up off the coast of Normandy on June 6, 1944, providing cover for American, British, and Canadian troops on D-Day.

The story of Pearl Harbor is also the story of two naval commanders, Kimmel and Isoroku Yamamoto. Give us a psychological profile—and explain how and why Yamamoto outfoxed his opponent.

Yamamoto and Kimmel were extremely different in personality. Yamamoto was a very sentimental guy, a bit of a romanticist. He also was, at heart, a gambler. He liked to tell people that if he had another life, he would live in Monaco and play the gaming tables. He pushed the plan for Pearl Harbor against the objections of many within the Imperial Navy. At one point, he said, “You have told me that this is a great risk, but I like speculative games and I’m going to do this.”

Kimmel was very much a disciplinarian, a by-the-book, laser-focused guy who tolerated no deviation from rules and regulations. He was obsessed with taking the offense as soon as war broke out, which in a way is a good thing. But he should have gone much more to a defensive posture, and he didn’t because he didn’t want to. He wanted to go attack somebody. That was the reason he didn’t send out search planes. He wanted to use them for his grand offense as soon as the war broke out.

Kimmel did not think a surprise attack was a possibility. The Americans had actually war-gamed the possibility that Japan could do this, but it was like one of those mental exercises you do for the record but don’t take to heart.

Kimmel also didn’t have a sense of the looming power of aircraft carriers. Aircraft carriers were only about 20 years old as a weapon. It was hard to imagine how much damage could be inflicted if 350 planes suddenly arrived from the sea, because that had never happened before. Nobody had put together a fleet with so many aircraft carriers at one time as the Japanese did on December 7.

Satellite technology, massively improved radar, and espionage make it unlikely that such a surprise attack could occur today. Talk about the difference between then and now.

We have to remember that in that day and age there were no satellites peering down, revealing all. So when the Japanese set sail on November 26, 1941, we did not know that. In their journey 3,000 miles across the Pacific, they never encountered a commercial ship, a search plane, a warship, and were never seen from above. It was the essential ingredient of their plan. They had to achieve surprise. If they didn’t, everything would have failed.

I don’t think there will be another Pearl Harbor because the ability to detect movement of armed forces is so much better, not just with satellites but also with listening devices and the ability of nations to suck up the radio transmissions of their opponents.

We can have a Pearl Harbor these days, but it will be pulled off by independent actors, such as on September 11, 2001. And those kinds of surprise attacks will probably always occur. But I don’t think we will have a classic military confrontation that begins with a massive, surprise attack that the victim never saw coming.

Tease out the similarities between Pearl Harbor and 9/11.

It’s a bit ghoulish to compare tragedies as to which was worse, so I’m not going to do that. But in both cases the sudden arrival of mass destruction and death pulverized America’s sense of itself. I would offer this difference. As soon as the attack became news in 1941, Americans knew they were immediately in the midst of a giant world war and that their sons, brothers, husbands, and fathers were going to be going off to war in faraway places.

It was popular to say that 9/11 changed everything, but it didn’t in the way Americans in 1941 knew it was going to change. America had been sitting out the war while France, Britain, Russia, and others were at war with Germany. Pearl Harbor changed that overnight.

What can we learn from Pearl Harbor today?

It’s wise, in management, to allow your subordinates to be creative and come up with their own solutions. But it’s not wise to then consciously remain ignorant of the choices they’ve made.

A second thing, which is particularly true of what happened with Admiral Kimmel, is that you shouldn’t let your desires color new facts. Kimmel just wouldn’t switch from what he wanted to do to what he should be doing.

Finally, if you’ve commissioned someone to do a report on something and they come back and forecast the future, don’t forget it! One of the most remarkable things about Pearl Harbor is that the nature and scope of the attack were exactly forecast only a few months before it happened by an admiral and a general.

The admiral was on Oahu in the days before the attack. But no one went to him and said, “You know the scenario you talked about where aircraft carriers might sneak up on our island? That may be happening right now because we cannot find the location of most of the Japanese aircraft carriers.” No one said that. He was ignorant–until the bombs started falling.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.