How one heroic crew helped win World War II’s largest naval battle

Outnumbered and outgunned, the crew of the U.S.S. Johnston fought overwhelming odds before their ship sank more than 21,000 feet into one of the world’s deepest submarine chasms.

Early in the morning on October 25, 1944, just east of the Philippine island of Samar, a lightly armed U.S. Navy task unit of six small escort carriers, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts found itself squaring off against a vastly superior Japanese flotilla of 11 destroyers, two light cruisers, six heavy cruisers, and four battleships—including the Yamato, the largest and most powerfully armed battleship ever built.

Retreat was not an option. At stake for the Americans at this stage in World War II was the success of their landing on the island of Leyte and Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s ultimate retaking of the Philippines. Three task units—code-named Taffy 1, Taffy 2, and Taffy 3—were there to provide shore support for the 130,000 men of the Sixth Army who’d landed on Leyte five days earlier, not to go toe-to-toe with the cream of the Imperial Japanese Navy. But with the mighty U.S. Third Fleet lured away in pursuit of a decoy fleet of Japanese ships, the Seventh Fleet engaged in conflict far to the south, and Taffy 1 and Taffy 2 some 25 miles to the southeast, Taffy 3 became the last line of naval defense for the men on shore.

Despite overwhelming odds Taffy 3’s carrier planes dominated the air above the ships and were joined by planes from Taffy 2. Taffy 3 attacked with such ferocity, its destroyers charging the battleships and heavy cruisers and launching torpedo attacks, that it was the Japanese who retreated, possibly assuming the task unit’s escort carriers were fleet carriers with large numbers of fighters and bombers primed for action. Their withdrawal, after three cruisers were sunk and a fourth badly damaged, handed the Americans a crucial strategic victory.

(How did a Japanese WWII submarine end up in Texas?)

Courage under fire

Success came at a heavy cost. Among the ships and men lost that day was the U.S.S. Johnston, a Fletcher-class destroyer that played a decisive role in the fighting. Its captain and crew continued to press home attack after attack even after they’d exhausted their supply of torpedoes and were reduced to firing smoke bombs and signal flares at the Japanese ships in the hope of setting them alight.

The Johnston’s captain, Cmdr. Ernest E. Evans, who was Creek and Cherokee, would become the first Native American awarded the Medal of Honor in the history of the U.S. Navy. His conduct that day included not only attacking in the face of insurmountable odds but also drawing enemy fire to save other ships. The Johnston’s crew would be awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for extraordinary heroism. For most of them, including Evans, the honors would come posthumously. Of the 327 men aboard the destroyer, only 141 survived.

So conspicuous was the courage and tenacity of the ship’s captain and crew that even as the shell-riddled destroyer rolled and slipped beneath the waves one of the Japanese destroyers, the Yukikaze, drew up to point-blank range not to fire but to offer a solemn parting salute.

(80 years later, you can still see the shadow of a Hiroshima bomb victim)

The Battle off Samar was one of four separate engagements that collectively became known as the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle in WWII, involving over 200,000 personnel and more than 360 American, Australian, and Japanese ships. It was also the first battle where Japanese aircraft carrier pilots carried out planned kamikaze attacks. Although the American task units at Samar were outgunned by the Japanese, in the other three engagements the Allies had overwhelming superiority. The Battle of Leyte Gulf was a comprehensive Allied victory, after which the Japanese Imperial Navy was a spent force.

Searching the abyss

Tracking down historic shipwrecks is always a challenge. But searching for ships sunk during the Battle off Samar takes wreck hunting to a new level. The confrontation took place in waters above the Philippine Trench, one of the deepest submarine trenches on the planet. Ships that sink here lie miles below the surface in a cold, dark world beyond the reach of all but a few highly specialized vehicles.

In 2019 the Johnston was discovered by just such a craft, the research vessel Petrel operated by the late Paul Allen’s Vulcan Inc., but was at a depth beyond the limit of the search equipment. The next person to see the Johnston was former U.S. Navy commander and millionaire adventurer Victor Vescovo, at the helm of a two-man deep-sea submersible called Limiting Factor whose 3.5-inch-thick titanium hull was designed to handle any depth. Having already used the Limiting Factor to visit the deepest points in each of the world’s five oceans, Vescovo decided in 2020 to turn his hand to finding the storied WWII destroyer.

A few months later, in March 2021, when the Limiting Factor’s searchlight beam illuminated the Johnston at a depth of 21,180 feet, or about four miles, it was the deepest shipwreck ever found.

(Nearly 80 years after World War II, their voices recall the struggle)

Such depths are hard to fathom—both literally and figuratively. Less than 2 percent of the world’s oceans are as deep as the submarine cliff on which the remains of the Johnston are poised. The famously deep and hard-to-reach wreck of the Titanic is a mere 12,500 feet below the surface.

The Johnston lies in what oceanographers call the hadal zone, also known as the hadalpelagic zone, named for Hades, the Greek god of the underworld. As with the mythical underworld, no light or warmth from the sun reaches this murky layer of the ocean at depths of between about 19,700 and 36,000 feet. Darkness reigns—the only occasional feeble glow being bioluminescence from the otherworldly creatures that inhabit these depths. Temperatures hover around freezing, and the pressure at 20,000 feet is a crushing four and a half tons per square inch.

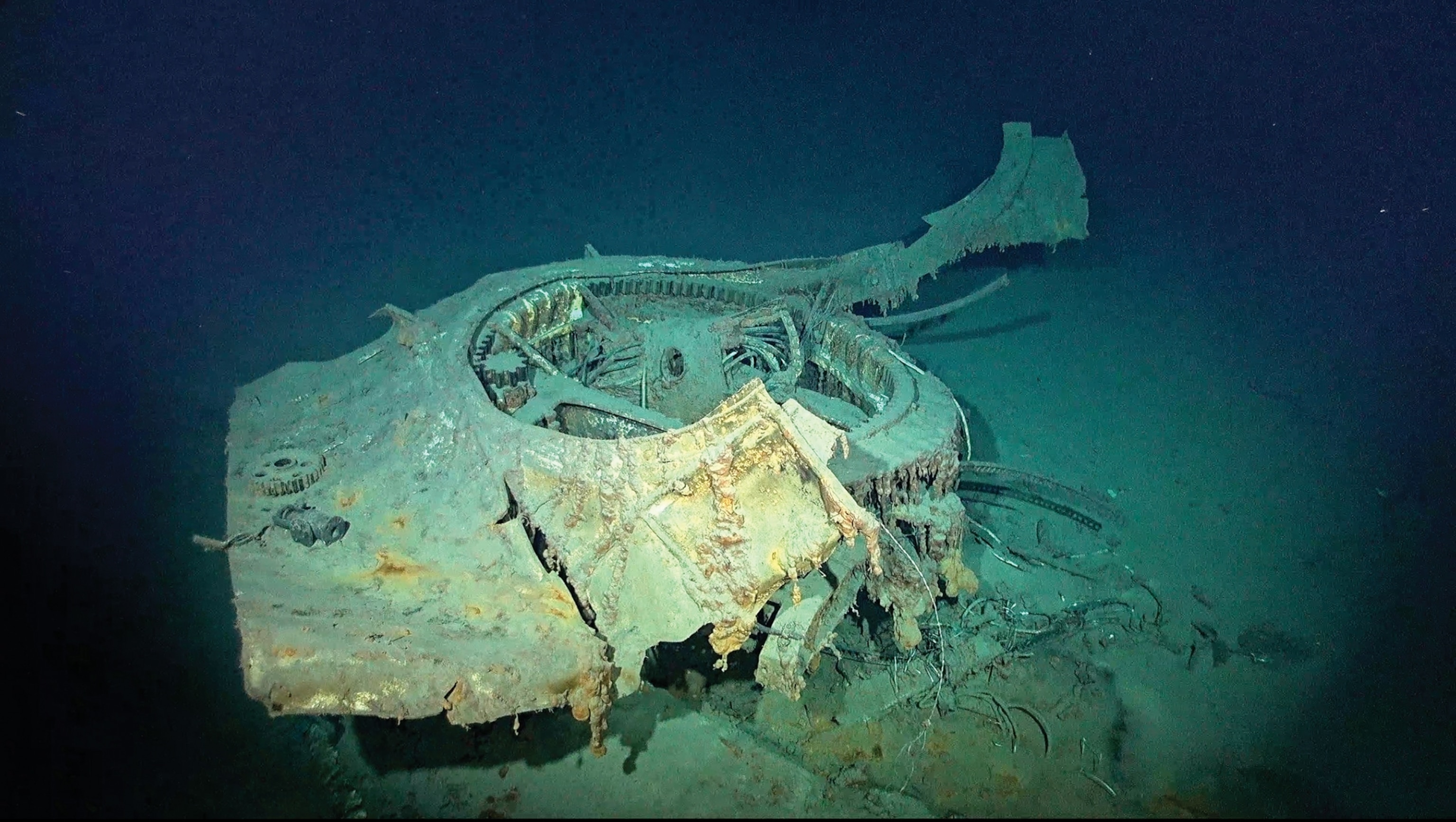

In two eight-hour dives, Vescovo filmed and surveyed the ghostly wreckage, noting details of the damage the Johnston sustained in the fray: its flanks shot through, the rear third of the ship missing where it was struck by an 18-inch shell from the mighty Japanese battleship Yamato, and a hole from a six-inch shell beneath the bridge. The wreck’s empty torpedo racks are an eloquent sign of the no-holds-barred fight the crew put up. Its five-inch guns still point to the starboard side in the direction of enemy ships when it sank.

(What everyone gets wrong about the deadliest shark attack in history)

Many other ships perished in the Battle off Samar. The Johnston would only briefly hold the distinction of being the world’s deepest shipwreck. Vescovo returned to the Philippines the following year and located the destroyer the U.S.S. Samuel B. Roberts at a depth of 22,621 feet—more than 1,400 feet deeper than the Johnston. The Sammy B. had also fought heroically to the end, sinking with the loss of 89 of its 224-man crew. Other wrecks from the battle may lie deeper still: The U.S.S. Hoel, the U.S.S. Gambier Bay, and several Japanese ships are yet to be found.