Decoding the lost scripts of the ancient world

Across the globe, a race is under way to crack some of the last mysterious forms of writing that have never been translated. Can new technology help scholars rewrite history?

The room we are in is locked. It is windowless and lit from above by a fluorescent bulb. In the hallway outside—two stories beneath the city of London—attendants in dark suits patrol silently, giving the scene an air of cinematic drama. We’re in the downtown safety deposit center where the Iranian British art collector Kambiz Mahboubian, keeper of one of the world’s great troves of Near Eastern ancient art, houses some of his more precious pieces under lock and key.

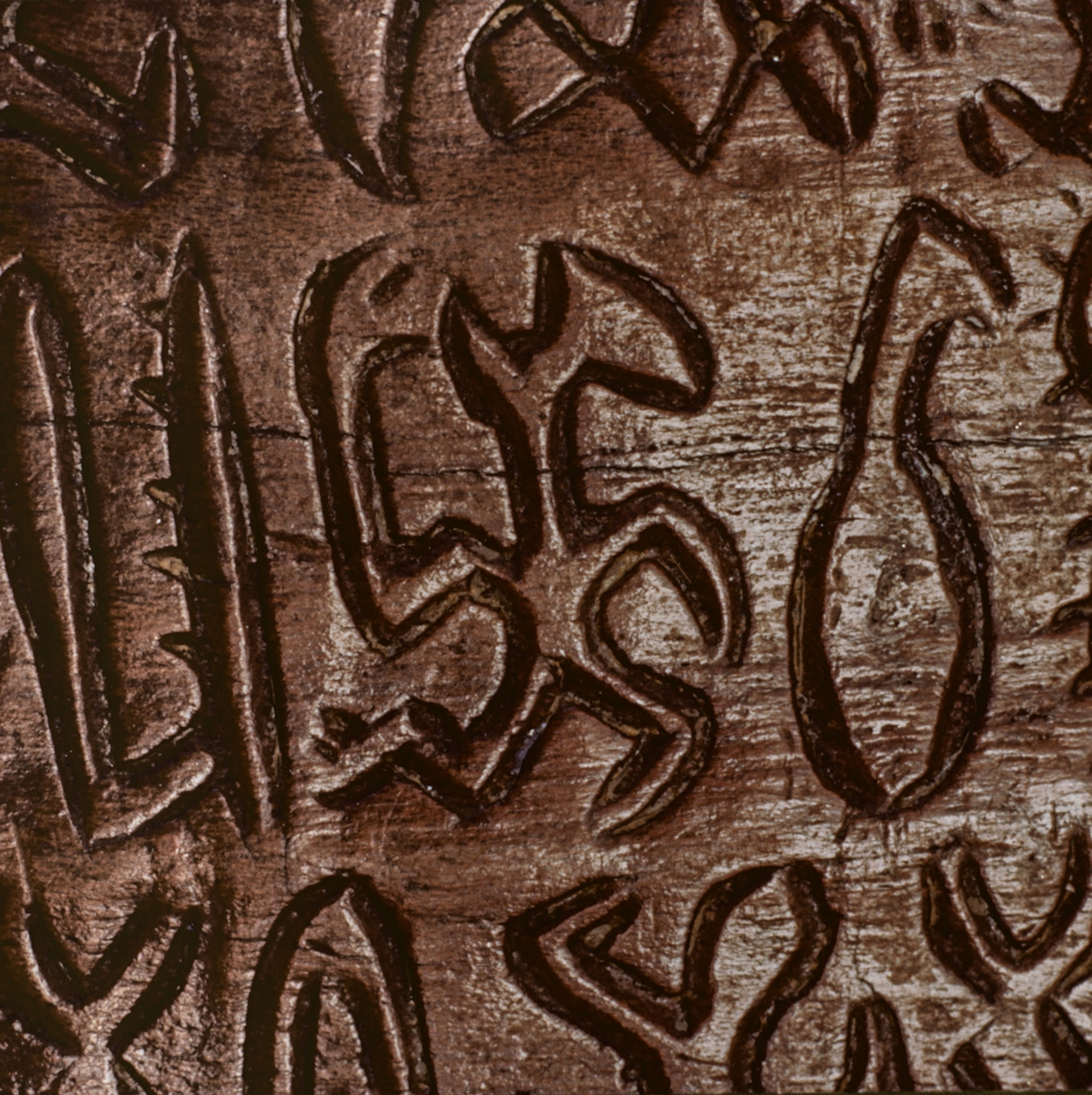

Sitting across from me at a small table, Mahboubian reaches gingerly into a green plastic shopping bag from Waitrose & Partners, the British supermarket chain. From it, he produces a silver beaker covered with friezes long ago hammered out in high relief. As he places the teakettle-size vessel on the table, I can see on it the image of a helmeted, barrel-chested man with a long, braided beard, his arms held outward in a gesture of devotion. Mahboubian motions for me to take a closer look. “Can I pick it up?” I ask him. “Of course,” he replies.

Neat rows of engraved symbols wrap around the object—asterisks, triangles with antenna-like appendages, hatched diamonds, lightning bolts. As I hold the beaker to the light, I catch a slight tremble in my hands: The metal is so soft and pliable that I fear it will break apart in my fingers. The beaker dates to the Early Bronze Age, meaning the craftsman who meticulously scratched these symbols into silver did so roughly 4,300 years ago. What they all mean has been a riddle that’s baffled archaeologists and historians.

The characters belong to a system of writing called Linear Elamite, which took root between 2700 and 2300 B.C. in a powerful kingdom called Elam, in what is now southwestern Iran. The Elamite writing system endured for several hundred years before it was swept aside by another script and lost to history. Then, just over a century ago, French archaeologists excavating the Elamite capital of Susa discovered 19 inscriptions written in stone and clay. The long sequences of signs clearly meant something. But what?

For decades, philologists studying the symbols in a quest to understand Linear Elamite made little progress for one big reason: The corpus of written material consisted of only about 40 inscriptions. The code-cracking researchers who piece together ancient languages generally rely on an abundance of symbols to spot repetitions, patterns, and sign clusters, the raw data that provide clues to grammar, syntax, names, and places.

One such scholar who fell into the seemingly impossible mission of making sense of Linear Elamite was François Desset, a French archaeologist whose curiosity turned into a 20-year journey to decipher the writing system. His recent headline-making claims of success have both galvanized public attention and incited skeptics. They’ve also underscored the idea that we might be at a pivotal moment in the study of these ancient scripts.

Today roughly a dozen forms of writing remain undeciphered. And a new generation of scholars has set forth, often with the aid of new technology, to reveal the last secrets of the ancients. Decipherers have used AI in recent years to locate archaeological sites, restore illegible texts, and analyze linguistic patterns to make inferences about grammar and vocabulary. But while AI has sped up the translations of languages and writings already known to a handful of scholars, the technology has yet to demonstrate the creativity needed to decode hitherto unknown scripts.

Indeed, creativity is what Desset summoned when he set out to understand Linear Elamite. His first conclusion was that he needed to find more examples of the script. Around 2004, he heard about the Mahboubian collection—the stockpile of Near Eastern treasures that the family claims had initially been acquired by Mahboubian’s grandfather, a physician turned archaeologist named Benjamin Mahboubian. The collection included 10 silver vessels and fragments, known as kunanki, decorated with images and covered by Linear Elamite inscriptions. The family has long maintained that Benjamin Mahboubian uncovered the art himself in a tomb in Kamfiruz, in southwestern Iran. “He found them all in one place,” Kambiz Mahboubian told me, “and then he sent them all to Paris,” where they remained with relatives before making their way to London.

But experts have challenged the authenticity of the kunanki. The family has no documents proving their provenance. The Mahboubians fled Tehran just before the toppling of the shah in 1979, and arrived in London, where they became prominent art dealers.

Desset, eager to get his eyes on what he imagined to be Linear Elamite, reached out to the Mahboubians, who ignored his approaches for years. Then a British Museum curator they trusted made an introduction. In 2015, the kunanki, which had been stored in the London vault, were delivered by a security team to the home of Mahboubian’s sister, Roya, where Desset was at last permitted to inspect them.

What Desset found amazed him. Laid out before him, he could see rows of symbols wrapping around beakers, cups, and fragments of broken vessels. He was elated as he snapped hundreds of photographs—documenting everything while suspecting he might never see the artifacts again. He told me that he thought, “Maybe this will be the last time; I should get all the information possible.”

Desset says that the visit to Roya Mahboubian’s home had vastly increased the number of symbols available to him. And he hoped that among the symbols he might find the missing link he had yearned for—the break that would allow him to solve one of archaeology’s most vexing puzzles.

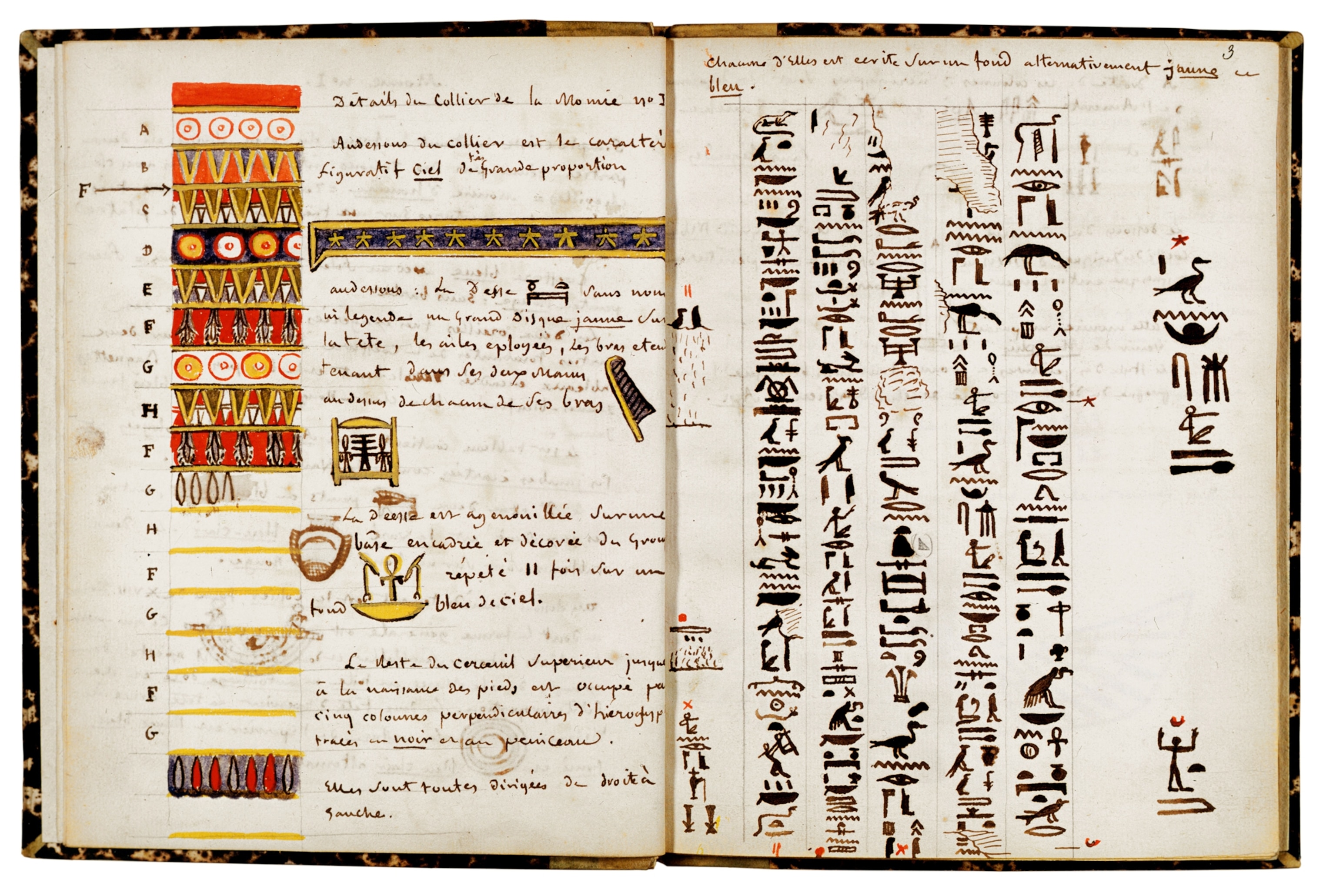

Every now and again, there are moments when history seems to lift its veil and the secrets of long-lost scripts are freshly revealed. In the early 1800s, the discovery of the famed Rosetta stone ignited a competition between Englishman Thomas Young and Frenchman Jean-François Champollion to decrypt Egyptian hieroglyphs, the sacred writing of the pharaohs. Three decades later, the excavation of 2,500-year-old riverside palaces in northern Iraq set off a race between the Victorian scholars Henry Rawlinson and Edward Hincks to understand Assyro-Babylonian. Their breakthroughs captivated millions, stirred patriotic fervor, and made accessible the science, medicine, history, mythology, and quotidian life of some of the ancient world’s greatest civilizations.

Deciphering ancient writing reveals how people understood the world, organized their societies, and thought about love and death. The work reanimates the voices of kings and ordinary citizens alike, exposing dreams, insecurities, obsessions, and even humor. It makes the ancients human. And the scholarship under way now to recover and decipher some of the oldest and most mysterious writing is reshaping our view of how languages spread—and, in the case of Linear Elamite, how early writing itself might have begun.

Of course, the scripts that remain undeciphered occupy that category for a reason: They present extraordinary challenges. For instance, linguists have been working for a century to decipher Rongorongo, a collection of glyphs carved mostly into wood by the Rapa Nui people of Easter Island. Success has eluded the experts. Similarly, the ancient writing known as Etruscan, used from the seventh to the first century B.C. and found inscribed on clay tablets in Italy, has defied attempts to crack it for generations.

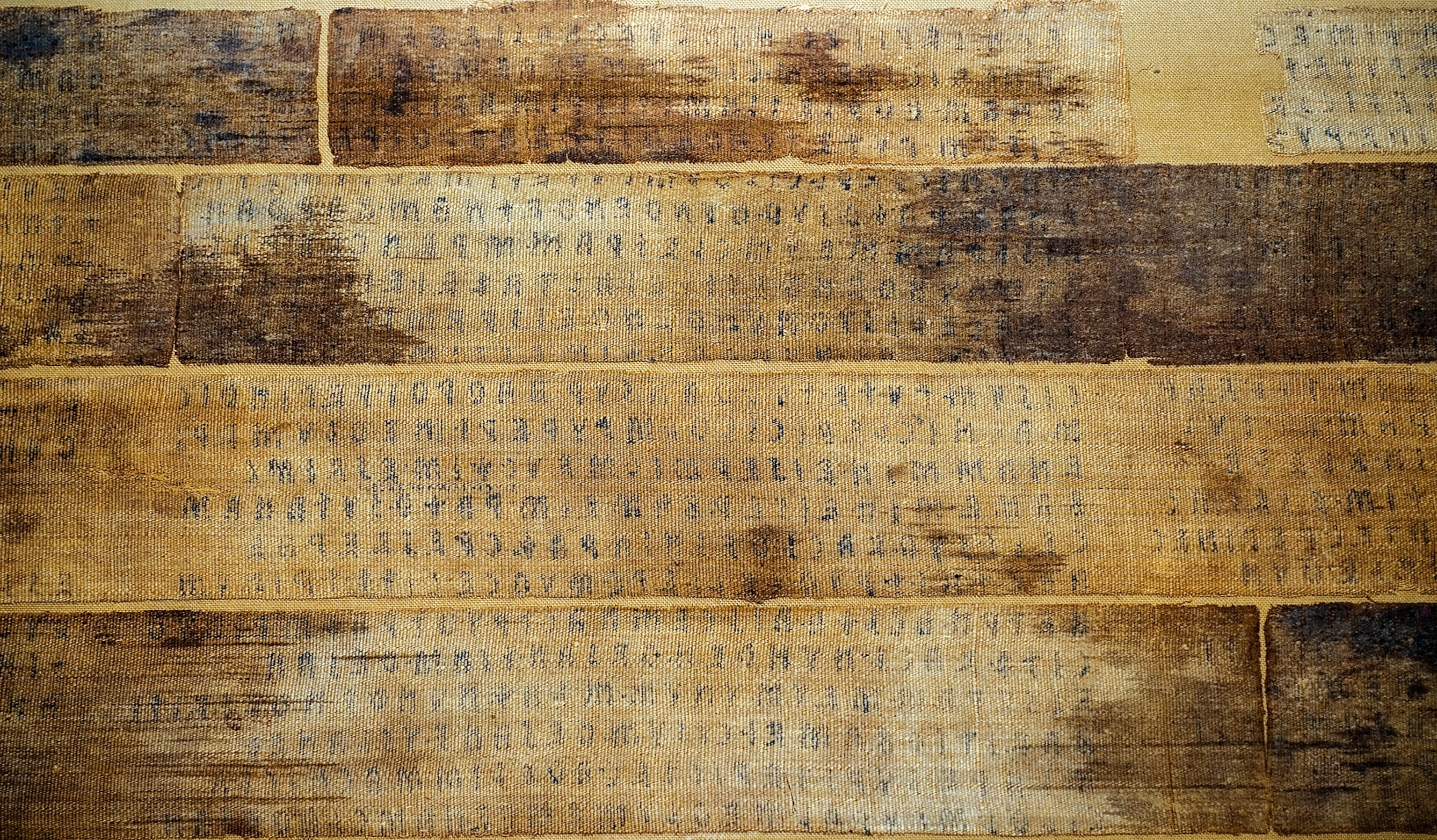

(What was the mystery message written on the mummy's wrappings?)

But the progress that is seemingly being made on several ancient systems—among them, a form of writing referred to as the Indus script; a system of writing called Linear A; and certainly, the advancements that François Desset captained on Linear Elamite—provide instructive insight on how new tools and fresh ideas might soon reveal some of history’s longest held secrets.

One drizzly morning in Chennai, India, the bustling capital of the state of Tamil Nadu, I rode in an auto-rickshaw out along the Bay of Bengal, traveling past a beach covered with wooden fishing boats and tin-roofed shacks. We turned onto a side street and stopped before a yellow concrete building marked “The Indus Research Centre.” Inside, I found Sukumar Rajagopal, a software engineer and amateur decipherer who has been working for more than 18 years on the Indus script. He was hunched over a pile of academic papers, immersed in what he calls “my obsession.”

Rajagopal describes himself as an irrepressible problem solver. He was 20 years into a software engineering career when he first grew intrigued by the ancient script, joining a long line of would-be decoders—professionals and amateurs alike who’ve tackled the Bronze Age script, perpetually optimistic that the critical breakthrough is right around the corner. Just last year, interest in the long-running project was given a major boost after the chief minister of Tamil Nadu offered a one-million-dollar prize to anyone who solved the mystery and could prove it. Not surprisingly, the bounty has ratcheted up the stakes in the hunt for solutions.

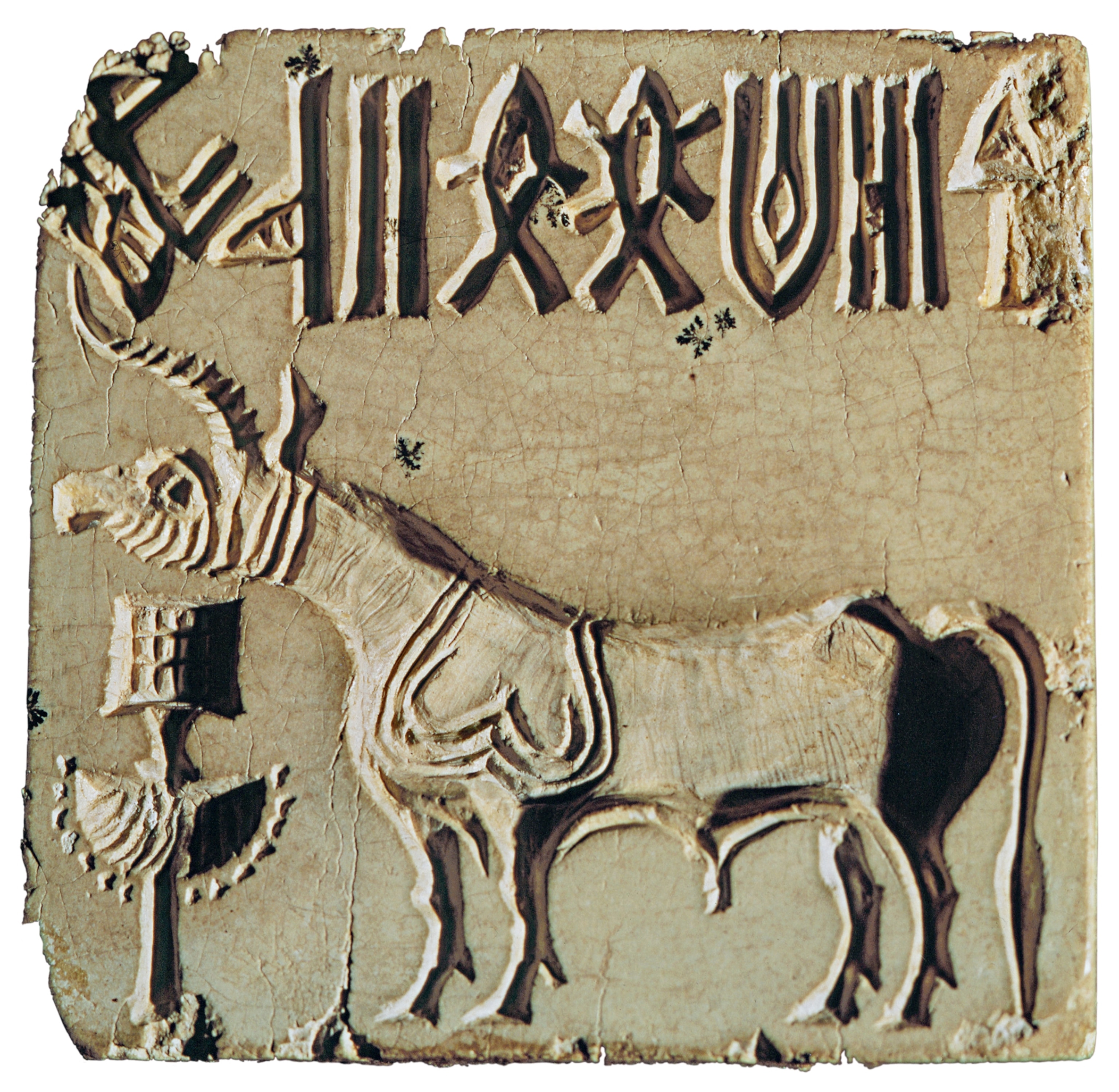

Back in the 1920s, when archaeologists found the script, they recognized its importance right away. Researchers had been working at two sites—Mohenjo Daro and Harappa—along the Indus River in what is now Pakistan when they located 2,400 small pieces of soapstone, as well as a few bits of ivory and clay, all engraved with what looked like both abstract characters and recognizable objects such as fish, water buffalo, plants, and humanlike stick figures. The British archaeologist leading the excavation, Sir John Marshall, theorized that they were looking at evidence of one of the world’s first literate societies, the achievements of which were, he wrote, “far in advance of anything to be found at that time in Babylone [sic] or on the banks of the Nile.”

If Marshall suspected that he was on the brink of unlocking something extraordinary, those hopes eventually fizzled. The inscriptions on the soapstone seals are frustratingly—maddeningly—short. Ninety percent of them consist of fewer than four characters; the longest has only 14. “What could you possibly communicate with that?” asks Rajagopal. In 2004, three noted scholars in the field published a paper titled “The Collapse of the Indus Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization.” In it, they posited that the signs say nothing at all.

More recently, the Indus Research Centre has become a gathering point for linguists and a locus of modern investigation into the script. Rajagopal began volunteering there in 2009. He had always nurtured a deep admiration for the great philologists of the past. “If there were a shrine for Champollion, I would be seen worshipping there,” he told me, referring to the decipherer of hieroglyphics. Now he was working among Champollion’s intellectual descendants, including Iravatham Mahadevan, an Indian epigraphist who helped establish the organization. Rajagopal told me that Mahadevan, who died in 2018, took him under his wing. “He converted what was a hobby in my head into a formal discipline.”

In the 1970s, Mahadevan, along with a colleague named Asko Parpola, a professor of Indology at the University of Helsinki, compiled separate lists of about 400 unique signs from the Indus script. The characters had been glimpsed on thousands of objects found across half a dozen archaeological sites. Next, they tried to determine what they were looking at.

Philologists know that all systems of writing fall into one of four categories. Some types use alphabets, composed generally of 25 to 35 signs denoting consonants and vowels that form words. Other writing depends on what’s called a syllabary, which is a symbol used to represent a combination—consonant-vowel, vowel-consonant, or consonant-vowel-consonant—that comes together to form words. A third form of writing is known as logographic (Chinese, for example) and is composed of a galaxy of unique signs, often numbering in the high thousands, each standing for an object, an action, or an idea. The final category includes hybrid systems like hieroglyphics or Japanese that mix logograms and a phonetic alphabet.

If the Indus script was indeed real writing and not random combinations of characters, Mahadevan and Parpola figured it likely belonged in the hybrid category as a mix of distinct word components, or phonemes, and logograms. Based on what they knew of other ancient forms of writing, they also theorized that the script could have been built upon an underlying language that in some form might still be spoken. This is one of the great tools used in the detective work of ancient philology: Figure out the sounds that the characters make, string them together, and you might conjure up the meanings as well. By comparing scraps and pieces—by triangulating what is known with what is mysterious—researchers can inch their way toward clarity.

After some hunting, Mahadevan and Parpola agreed that the Indus script was likely built on “Proto-Dravidian,” a nascent form of language that many philologists believe dominated the Indian subcontinent during the Early Bronze Age. The ancient language was lost, but vestiges remain in modern Tamil and other southern Indian tongues.

Parpola then zeroed in on the most prevalent sign in the script: a fishlike character that the professor believed was a logogram. In Tamil, Parpola knew, the word for “fish” is min. But min has a second meaning: “star.” “All early scripts had the rebus principle,” Parpola, now retired and living in Helsinki, told me: using a pictogram or symbol for its sound, not its meaning. For example, in the world’s first writing system, Sumerian cuneiform, scribes combined the pictogram for barley, which has the phonetic value “she,” with the symbol for milk, which connotes the sound “gah,” to make “she-gah,” which had nothing to do with barley or milk but meant “pleasing.”

Following these principles, Parpola, over several years in the late 1960s and early 1970s, searched for other clues. He found in the Indus script another symbol that showed a fish divided down the middle by a vertical line. The line, he proposed, stood for pasu, the ancient Tamil word for “half.” But pasu also means “green.” If the fish connoted “min,” he now had a rebus: pasu-min, or “green star,” which he took to mean the planet Mercury.

Pushing further, Parpola found what he thinks are rebuses for Saturn, Venus, and other stars. He also located what he believes were a few purely phonetic signs. What did it all signify? Because the inscriptions are so short, Parpola believes that they contain no grammar, no full sentences, no elements of real writing. He posits that they never were intended to communicate messages but rather were used as the markers of citizens who were named after celestial objects, like many rulers of the age, including those in Assyria and Babylonia.

Of course, decoding work like this that relies on interpretation and speculation prompts disagreement. Mahadevan parted ways with his colleague on many of Parpola’s readings, beginning with the fish sign, which, Mahadevan believed, had nothing to do with astronomy. It was, he contended, the sign for a sea nymph, a creature prevalent in Indian mythology. But the brevity of the inscriptions and the uncertainty about the language meant that neither scholar could say he solved the riddle.

Rajagopal, for one, thought that Parpola was on the right track. A few years ago, he began to fixate on one seal that consisted of a row of five rotating swastikas, a sacred symbol in many ancient religions, followed by two parallel vertical lines. Parpola had claimed that the double line formed part of a rebus for the planet Venus (when combined with the fish, he said, it made VeLi-Min, or “bright star”), but the swastikas remained an enigma.

Rajagopal told me he was consumed by the mystery of the sequence and thought about it constantly: “I was going down a rabbit hole.” One morning in November 2020, while sitting in his home office in Chennai, he chanced upon a NASA website that traced the trajectory of Venus as it moved across the morning and evening skies. He stopped and stared at his computer screen. The double-snake-like pattern formed by the planet’s path looked just like the swastika he’d been studying. “I got the goose bumps,” he says.

With that, he was off and running. The inscription, he theorized, had to be a celestial omen signifying the completion of Venus’s eight-year cycle as it orbited the sun and returned to the same position in the sky. He looked for similar astronomical depictions. Another seal, he proposed, showed the alignment of three planets. Half of the seals, he now believes, identify celestial events. Rajagopal theorizes that they were written so that Indus Valley priests could dispatch these seals to villages to provide guidance for the timing of crop plantings and harvest festivals.

Rajagopal now claims to have deciphered “with confidence” 70 seals out of 4,200. He finds it difficult to pull himself away. “I will take some seal and keep obsessing, and somehow I get an idea and push it forward,” he told me. “Many times, I hit a dead end, and then I’ve got to spin the next hypothesis and try again.”

Not everybody accepts his interpretations—and the public attention around Rajagopal’s progress has only highlighted how tricky this work can be. At a 2023 Indus script conference in Chennai, a fellow decipherer stood up during his lecture and ridiculed him. Another amateur scholar in Chennai, Sumangali Kidambi Venkatesan, says that Rajagopal’s celestial theory is misguided and that most seals were simply shipping instructions—Bronze Age versions of DHL waybills. Venkatesan says he has found his own Dravidian-based rebuses, which are nothing like Rajagopal’s. One inscription, Venkatesan told me, consists of a combination of logograms and phonetic signs and refers to the highlands of Afghanistan. He translates it to read: “Very clever trapper Velappan of the triple mountain sends by boat along the big river by care to the tiller of land.”

The range of disagreement and the volume of theories underscore the intensity of the enduring debate as well as the idea that would-be code breakers may never reach a consensus. Even the Dravidian hypothesis itself is challenged. Some scholars argue that the underlying language of the Indus script is Sanskrit, the basis of Hindi. One decipherer claimed to have identified rebuses for the gods Shiva and Indra, mentioned in the ancient Sanskrit religious text known as the Rig Veda. Like nearly everything in India, ethnocentrism is fueling the debate. Many Tamils want to bolster claims that their ancestors, not northern Hindi speakers, created India’s first urban civilization.

A few hundred miles southwest of Chennai, archaeologists recently found glyphs scratched into clay tablets at Keeladi, a 2,600-year-old site, that match signs from Mohenjo Daro. This, they insist, is evidence of a connection between the Dravidian culture of southern India and the original settlers of the Indus Valley. “Of the 50 different signs, we have 29 perfect matches,” Ramesh Masethung, Keeladi’s chief archaeological officer, told me as he escorted me around a football-field-size excavation pit in a grove of coconut palms in rural Tamil Nadu. But if Sanskrit is in fact the underlying language beneath the Indus script, Rajagopal and many others will be sent back to the drawing board—and that million-dollar reward will seem further away than ever.

The great hope among philologists today is that the breakthroughs lurking right around the corner will be ushered in thanks to tools and technologies that their predecessors never dreamed of. Francesco Perono Cacciafoco, a 45-year-old professor of linguistics at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University in China, has devoted more than half his life to trying to decipher another Bronze Age script called Linear A. The writing system was used by the Minoan civilization of Crete—the predecessor of the Mycenaean Greeks—from about 1800 to 1450 B.C. The problem has been that the Minoans seemingly employed a language unrelated to any dialect of ancient Greek—or, apparently, any other known language from that time period.

When he began studying the writing in 1999, Perono Cacciafoco noticed that the system used many of the same characters as a Cretan syllabary called Linear B, deciphered by English scholar Michael Ventris half a century earlier. But the characters of Linear A formed words that bore no resemblance to those of Linear B. “If you try to read the corresponding symbols, it’s not Greek,” Perono Cacciafoco told me. “It’s gibberish.”

Where Parpola’s quest to understand the Indus script had led him to philological research into ancient Dravidian, Perono Cacciafoco took a different path. In 2017, he assembled a team of 16 mathematicians, engineers, and linguists, and designed what they called the “Linear A Decipherment Programme.” The team fed into the computer the vocabularies and grammatical structures of deciphered ancient languages from across the Mediterranean area—ancient Egyptian, Luwian, Assyro-Babylonian, Aramaic, Amharic, and Hittite, to name just a few—and asked the program to compare the words with possible transliterations of Linear A. They hoped that the comparison would find similar etymological roots. But after three years, “the Machine,” as Perono Cacciafoco called it, had found no matches. In 2020, funding for the project ran dry, the pandemic shuttered the university, and the project was put on hold. Computer programs, he had come to believe, aren’t totally up to the task. Now Perono Cacciafoco’s team is using a modified version in the hope that it will produce better results.

Artificial intelligence, Perono Cacciafoco says, will probably never be able to decipher an undeciphered language, because it’s not able to produce original thought or intuitive connections. What it could do, he explains, is speed up the deciphering process by recognizing patterns and making statistical calculations about the appearances of certain characters in unknown texts. In 2023, researchers from MIT and Google’s DeepMind tested AI tools on previously deciphered Linear B texts and were impressed by the ease with which the programs worked. The system “got it about 60 percent right,” says Andreas Fuls, an engineer at Berlin’s Technical University, one of those attempting to decipher both the Indus script and the mysterious writing on what’s known as the Phaistos disk—an ancient clay saucer found on Crete that contains a spiraling inscription in an unknown writing.

In those experiments, the AI was primed with the knowledge that Linear B was an ancestor of ancient Greek. It turns out that AI is excellent at comparing a script to other members of the same linguistic family. But when asked to decode a script written in an unknown language that has no relationship to other tongues, AI still struggles. This, says François Desset, the philologist unraveling Linear Elamite, is because the technology, at least currently, lacks the ability to “think creatively … to come up with something out of nowhere.”

On a recent morning in France’s Loire Valley, I met Desset at his apartment in the city of Angers. Tousle-haired and goateed, he was happy to describe for me that moment in 2015 when he finally got to see the Mahboubian family’s prized kunanki.

For years, though, his efforts to decipher Linear Elamite had been stymied by the paucity of inscriptions. Unlike hieroglyphs, which covered temples and tombs along the Nile, or Akkadian cuneiform, inscribed on palace walls and clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamian cities, Linear Elamite was rare. “Writing didn’t seem to play the same central role for the Elamites,” Desset says.

After much floundering and frustration, he found himself in Roya Mahboubian’s elegant North London apartment, examining an academic gold mine: 759 Linear Elamite signs engraved on 10 cups and fragments, plus inscriptions in cuneiform. “I was thinking, Eureka,” he told me. “But I was also skeptical. Everybody in the academic world was sure it was all fake.” But Desset nursed a conviction that the kunanki had to be authentic; no forger could have strung together so many Linear Elamite signs that actually contained bits of coherent text. Later tests by a metallurgist in Italy confirmed that the kunanki were made of a 90 percent silver, 10 percent copper alloy consistent with other vessels from the period.

Even though philologists had long ago determined that the language spoken in ancient Elam had no known relatives, Desset did have one tool at his disposal—something that for centuries had aided those who study antiquity. Sometimes, when a message was committed to writing on a tablet or a piece of art, the same or similar information was inscribed in several languages and scripts at once. This practice helped the scribes reach the largest audience possible. Thousands of years later, that habit has helped philologists who can compare deciphered writing with the adjacent undeciphered script. Desset had just such a bilingual inscription that he hoped could provide clues to some of Linear Elamite’s phonetic values. Archaeologists at Susa in 1903 had turned up a limestone artifact called the Table au Lion, now on display at the Louvre. The kings of Elam had often inscribed Linear Elamite side by side with inscriptions in Akkadian cuneiform, the writing of nearby Mesopotamia, which had been deciphered in the 1850s.

In 1905, the German linguist Ferdinand Bork noticed a sequence of four Linear Elamite characters on the Table au Lion that appeared twice. The adjacent Akkadian text also had four characters that showed up with the same frequency. These cuneiform signs formed part of two names: Puzur-Sušinak, the last king of Elam’s Awan dynasty, and the Elamite god Insušinak. From these parallel sign patterns, Bork deduced that the Elamite characters must be su, shi, na, and k. That gave him pu, zu, and r, as well—for a total of seven characters. From there, the decipherment stalled. The trouble was, for decades, there just wasn’t that much Linear Elamite in existence. Could Desset’s new trove change everything?

Early one morning in spring 2017, he sat before his laptop in his apartment near the University of Tehran, where he was teaching. The screen glowed with Linear Elamite characters, which Desset had copied by hand and digitized from the photos he had taken. His eyes settled on a four-sign pattern from one of the kunanki. It showed up repeatedly. He recognized the first sign in the sequence immediately; it was shi, as Bork had first seen in Puzur-Sušinak.

Then came three unknown signs—the last two of which were identical. In a flash, Desset could see it: The duplicated sign was ha, which formed the last syllables of Ši-l-ha-ha, an early second millennium B.C. Elamite king. Minutes later, Desset spotted another repeated sequence, with one recognizable sign: r. In cuneiform texts, he knew, Šilhaha was often mentioned with who is most likely his father: E-pa-r-ti. In 15 minutes, Desset had acquired the values of five signs. Thrilled, he plugged the sounds into the texts and spotted other names, leading to his identification of more signs.

For the next few years, Desset continued making progress. He had assumed from the start of his studies that Linear Elamite, like all other writing systems from the Early Bronze Age, was mixed. “I was looking for logograms, saying, Where the hell are they?” he said. But as his knowledge of the signs deepened, Desset took what he calls “a creative leap.” Linear Elamite, he now perceived, was a purely phonetic script, with 77 signs, including five vowels and 12 consonants. Until now, it was widely accepted among linguists that the oldest purely phonetic alphabet was Proto-Sinaitic, a Middle Bronze Age script from the Sinai Peninsula, which appeared 500 years after Linear Elamite. Desset’s analysis, if verified by other philologists, could force a radical reconsideration of the history of writing and human progress. It would reorder the chronology of phonetic writing, shifting the focus away from the Levant to the Iranian plateau. It would also elevate the previously overlooked Elamite kingdom to a primary place in human intellectual development. Seven years after that encounter in London, in 2022, Desset and four colleagues authored an article in Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie (Journal for Assyriology and Near-Eastern Archaeology), a respected journal published in Berlin. The phonetic values of every Linear Elamite character, they declared, had been deciphered at last.

The claim was remarkable. If true, it represents the first time that all the sounds of an ancient script have been figured out in decades. But Desset and his team, he admits, haven’t accomplished a 100 percent decipherment of the writing system. According to most philologists, real decipherment occurs only when a script’s sounds and its meaning are both understood. Champollion had determined the meaning of hieroglyphs after sounding out some words and recognizing that the language must be a direct ancestor of Coptic Egyptian; Hincks and Rawlinson were able to understand Akkadian cuneiform after perceiving that the underlying language closely resembled Hebrew. But the language of Linear Elamite—known simply as Elamite—remains largely a mystery.

Thanks to the inscriptions on the kunanki, Desset has managed to tease out not just the names of places and kings but also a smattering of titles, epithets, common nouns, adjectives, and verbs. One silver beaker, he suggests, was an offering given by a ruler to the Elamite supreme god. “I Pala-išan … mighty lord,” the inscription reads in part, “I am the servant of Napireša.” Desset found the words kere, which he translates as “devotion” or “worship,” and zeni, a divine blessing bestowed by a god on his royal subject. Other words, including zemt for “king,” hort for “people,” and shak for “son,” also became clear in context. “It shines a little light on this long-vanished place,” he says. Today, of the 1,863 Linear Elamite signs that exist in the corpus, Desset says he is able to sound out 1,810 of them—the rest have eroded into illegibility—but, he acknowledges, he can make sense of only a few words. “I am still facing a lot of problems with the translation,” he told me.

He faces critics too. Jacob Dahl, an Oxford professor considered one of the world’s foremost scholars of Mesopotamia, disputes Desset’s assertion that Linear Elamite is a purely syllabic script. “That part of the decipherment is certainly not correct,” he told me. “I would suspect there were logograms as well.” He also says that so much about the script remains unknown—the meaning of many words, the grammar, the values of certain signs—that Desset’s claims of victory are wildly premature. “I have little patience for Desset,” Dahl told me. “Much of it is complete rubbish.”

Desset has tried to shrug off the criticism. Since the announcement of the Linear Elamite decipherment, he told me, escorting me to the door of his apartment, “I have found new friends, and I have found new enemies.” His next undertaking is an attempt to decipher Proto-Elamite, a precursor to Linear Elamite that first appeared in the fourth millennium B.C. and represents the earliest stage of civilization in Iran. The writing consists of 400 to 800 characters, the hallmark of a logographic-syllabic system. “It is a total mystery,” he says. Just the kind of challenge that code breakers love.