Can TikTok resurrect Scots?

Inside the decidedly modern campaign to revitalize a lost language (that some say isn’t truly a language).

When “hurkle-durkle” went viral on social media a couple of years ago, most of the people using the phrase had only a faint idea what language it came from—but not Len Pennie.

Pennie is a poet and Scots language influencer with more than a million followers on Instagram, TikTok, and other platforms. Originally from just outside Glasgow, the 26-year-old appreciates that people connected with hurkle-durkle as a fun, funny-sounding way to say “lounge in bed when one should be up and about”—just like how the cozy, convivial concept of hygge, from Danish and Norwegian, entered the zeitgeist years before.

But old-fashioned hurkle-durkle “is not a word that most people in Scotland are going to know,” says Pennie. Partly because it’s the linguistic equivalent of a penny-farthing (an early type of bicycle). And partly because Scots has been hiding in plain sight, even in its homeland, for decades. Lately, however, with the help of young ambassadors and activists like Pennie, Scots is making itself known—not just on TikTok, but in everyday life.

Today Scots is spoken by roughly 1.5 million people (with almost another million having some understanding of the language), which, in a country of about 5.5 million, is no small amount. Last year, it was granted official status by the government alongside Gaelic, which is spoken by some 130,000 people. But Scots still lives in the shadow of English, the dominant language in Scotland. Historically spoken mostly south and east of the Highlands, Scots was the nation’s quasi-official tongue, complete with a growing literature, until the union with England in 1707 put English decisively on top. After that, it was considered the language of the uneducated, no matter how beloved Robert Burns’s “light Scots” verse was. Within living memory, you could get corporal punishment for speaking it at school. Even now, Scots still carries a kind of hillbilly stigma.

Pushing back on that attitude while battling for the hearts and minds (or, perhaps, the tongues and ears) of non-Scots speakers is a younger generation of creatives—singers, writers, social media natives, and others—reviving and reinventing the language for the 21st century. In their 20s and 30s, hailing from all over the country, they’re bringing Scots into TikToks and text messages, pop music covers and poetry.

“This has just all come out of nowhere,” says Pennie of her own trajectory, as she steps out of the BBC Scotland studios in Glasgow, where she hosts a four-times-weekly, Scots-inflected radio show on arts and culture. (It’s not lost on her that she broadcasts from inside what was once a famous bastion of “proper” English.) During the COVID pandemic, Pennie’s therapist advised her to get a hobby. Cross-stitching hurt her hands too much, so she started writing poetry and sharing it online. One poem in particular, part love letter to her mother and grandmother, part language lesson, went viral. Within its lines, an italicized phrase in English is challenged by its equivalent in Scots:

“I’m no havin children, A’m gonnae hae weans;

an ye’ll can ask whit A cry them, no what are their names … ”

Pennie went on to publish an award-wining poetry collection in 2024, with a follow-up volume this past fall—both in a mix of the two languages. Meanwhile, her social media fans (70 percent of them in the United States) hang on her Scots word of the day. Recent examples include smookit, a “sly or crafty person,” as in, an awfy smookit wee smout (an awfully sly yet insignificant person), and prinkle, meaning “glitter,” as in, his een aye prinkle (his eyes always glitter).

Squint and you can see that plenty of Scots words are close cognates with English ones. But where Scots has long been considered a dialect, plenty of linguists insist it’s really more a sister language of English, with its own distinct vocabulary, grammar, and resonance. That’s complicated by the fact that it’s not uncommon for speakers to move between English and Scots. There are different spellings, pronunciations, and usages. “The Doric [Scots dialect] of the Northeast and Aberdeenshire is different to the Scots of Ayrshire and Galloway, and different again to Glaswegian Scots,” says Emma Harper, a Scottish Parliament member who championed Scots officialization. Pennie and other activists often reflect this interwoven reality, while also challenging listeners to figure certain things out for themselves. “Everyone’s got their own standard,” Pennie says.

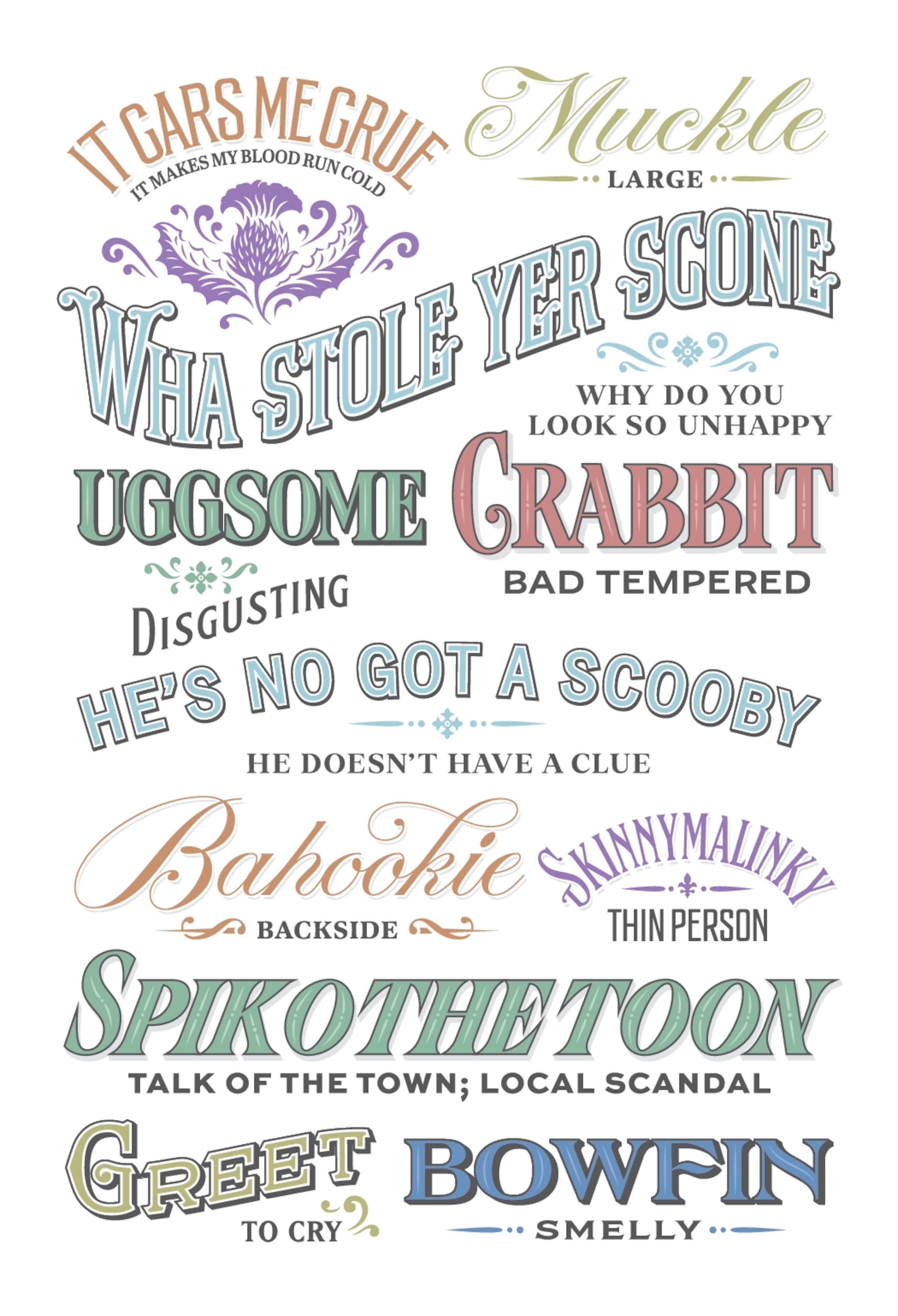

While many Scots speakers celebrate all this variety, others hope that official recognition will provide a degree of clarity, consistency, and active protection. The kind that will guard against, say, a North Carolina teenager who barely knew the language writing half of the entire Scots-language Wikipedia entry in a garbled pseudo-Scots for the better part of a decade (as was discovered in 2020). On the other side, some worry that viralities like hurkle-durkle just continue a history of not taking the language seriously—a process of cutesy commodification that Pennie links to “the tartan, tea towel, and kilt faux-identity that’s packaged for tourists.”

Parliamentarian Harper gives plenty of credit to the new cohort of influencers for helping keep the language, well, youthful. “Young people, like most Scots, code-switch on a daily basis, and as social media has integrated itself into their daily lives, so the code they use online is their day-to-day one—which in most cases is Scots,” says Harper. “It’s a good example of government matching its actions and legislation with the reality of what’s happening in society right now—thousands of young people using Scots on a daily basis, an ancient language in a very modern context.”

Further proof: Writers, musicians, and artists are taking Scots in new directions. While reading at the recent launch of his debut poetry collection, Goonie, Glaswegian poet Michael Mullen, 30, wearing a fabulously decorative suit, mixed languages as fluidly as he mixed talk of vodka and Irn-Bru (Scotland’s national soft drink) and queer New York icon Marsha P. Johnson. Across town at the Reeling, an annual traditional music festival, young singers like Beth Malcolm moved easily between Scots and English.

While the language melts into the cosmopolitan mix of a city like Glasgow, it’s up north in fishing communities like Fraserburgh and Peterhead that Scots (here often known as Doric) is sometimes said to be strongest.

Having grown up there, 37-year-old writer Shane Strachan is a bridge between a weathered Scots-speaking world anchored in pubs and ports (as well as farms and fairs) and the new language movement online and onstage. His own grandmother “barely speaks what would be perceived as English,” says Strachan, and she was “belted at school” for speaking her mother tongue. But as a former Scots Scriever (an official title, like a poet laureate), Strachan acts as a roving ambassador for the language. When he’s not teaching at the ancient University of Aberdeen, he visits hospitals and book festivals, and once hosted the annual, geekily glamorous Scots Language Awards. (“Glamour” is originally a Scots word meaning “magic” or “witchcraft” and deriving—believe it or not—from “grammar.”)

Strachan sees Scots’s revitalization being driven in part by young people’s desire for, as he puts it, “what’s left that makes you different” in an era of social media homogenization. A new generation of Scots speakers wants to talk about what’s happening in the world, in their own words. Strachan’s poetry collection DWAMS, named for a word meaning “a stupor, a trance; a day-dream, reverie” (at least, that’s one of six definitions in the Dictionaries of the Scots Language) touches on everything from the climate crisis to xenophobia to queer love and sex. In a recent spoken word performance, Strachan brought the house down with “Dreepin,” a poem in the form of “sexy” voice mails between Aberdeen and the oil industry it’s built upon.

Singer Iona Fyfe, born and raised near Aberdeen, expands Scots’s linguistic horizons through music. “I feel so much more comfortable singing Scots than I do speaking Scots,” says the 27-year-old, “because there’s an art form” that no one can argue with. Fyfe is steeped in the Scots ballads tradition but also writes new songs in the language—and has even recorded a Scots version of Taylor Swift’s “Love Story.” Letting Scots absorb pop culture through translation keeps it relevant, she points out. Now you’ll find books getting Scots versions, from Harry Potter to Animal Farm, children’s books to classical Chinese novels.

Of course, proof of Scots’s vitality is its presence in the myriad day-to-day conversations of a Gen Zer like Fyfe. Texting in Scots is “really normal nowadays,” she says. She posts in Scots—and about Scots—on every social media platform around, including TikTok, Bluesky, and Facebook. It helps that technology has made typing easier: You’ll find Scots support in browsers and predictive text. More futuristically (and controversially), ChatGPT can “write” in Scots, having trained on texts by authors from the past and present without permission.

Fyfe has modest hopes that the legal recognition of Scots as an official and national language by the Scottish Parliament will give “a wee bit mair encouragement” to speakers—proof that “just because you’re using Scots doesn’t mean that you’re lower class or uneducated.” More institutional backing could potentially lead to multilanguage signage (which happened in some areas for Gaelic), support for writers, and a presence in schools that goes beyond the poetry of Burns.

Scots’s existence is in some ways a microcosm of Scotland’s own political future, caught as it is between calls for independence and the potential to be absorbed deeper into the United Kingdom. The language’s youngest champions are using every modern medium at their disposal to keep it alive and vital. Though Len Pennie also points to nothing more cutting-edge than “a great Scots word, thrawn: stubborn pigheadedness.”