How the first woman defied a ban to climb Mount Fuji—and then was forgotten

In 1832, Tatsu Takayama made a defiant climb up to the top of Mount Fuji dressed as a man. This is the story of her historic journey.

The grave of Tatsu Takayama is unassuming and plain. She’s buried within Saishō-ji Temple, in a quiet corner of western Tokyo, under a stone pillar nearly indistinguishable from the others around it.

And yet the bones there carry with them the remarkable spirit of a woman whose reverence for the mountains—and courage to honor them—has long outlasted her story.

In 1832, Takayama became the first woman to summit Mount Fuji—which, at the time, was forbidden for women to climb. In defiance of common law and religious custom, she went anyway, disguised in men’s clothes, risking exile.

(Why hundreds of thousands climb Mount Fuji every year.)

Moments before reaching the summit, she told those accompanying her, “I want to climb up to the summit even if I should die at the moment when I reach it. If I can return home, I want to encourage all women to climb,” writes historian Fumiko Miyazaki in Female Pilgrims and Mt. Fuji: Changing Perspectives on the Exclusion of Women.

Though her accomplishment was extraordinary, her story has largely disappeared from public memory, overshadowed by the male-dominated records of early mountaineering in Japan and the limited preservation of women’s religious and climbing histories at the time.

“What she was doing wasn’t mountaineering in the modern sense. Climbing mountains in Japan then was a religious act, a pilgrimage—not a conquest,” says Barbara Ambros, a religious studies professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Because of that, women like Tatsu Takayama often disappeared from the record.”

Yet it underscores how exceptional Takayama’s climb was—a bold, rule-breaking act of devotion that deserves recognition alongside the earliest stories of mountaineering in Japan. The details of her story that remain, preserved in temple archives and family records, are sparse, but striking.

The banning of women from the mountain

Mount Fuji is not merely a mountain. For the Fuji-kō—a folk Buddhist-Shintō confraternity that flourished around Edo, in what is now Tokyo, during the Edo period (1603 to 1868)—it wasn’t a destination; it was a deity.

To climb it was to endure thin air in the name of devotion, the closest one could come to purification. To reach the summit was to stand among the gods.

Based in the Kanto region of Japan, the Fuji-kō organized structured pilgrimages to Mount Fuji, relying on oshi houses, or pilgrim inns, where priestly guides offered lodging, prayers, and ritual preparation for climbers.

For women, this reverence had limits. The Edo doctrine of nyonin kinsei, the “no women rule," cast them as ritually impure, a threat to the mountain’s sanctity—even as the mountain itself was worshipped as a female deity.

“It was thought that the mountain gods would be offended,” says Ambros. “Women were considered polluted through blood, so menstruation and childbirth. It was assumed that pollution was so inherent to them that it couldn’t be shed.”

(As we’ve told women’s stories, they’ve changed the world.)

Guards and checkpoints were staged upon the mountain to regulate pilgrims and reinforce the ban on women above certain altitudes; those caught were turned away or punished. Generations of Fuji-kō women prayed from afar, building shrines at the mountain’s base and sending their wishes upward through men. Some even built Fujizuka, small, climbable replicas of Mount Fuji, in order to perform the ascent symbolically.

Still, some women were not content with the symbolic climb. As Miyazaki writes in her book, “female pilgrims tried to climb as high up the mountain as they could whenever the opportunity presented itself,” defying the law that barred them.

“Tatsu wasn’t necessarily the only one that pushed for women to be able to go to the summit,” Ambros says. “She was embedded in this religion [that] had ideas about relationships between masculine and feminine that were perhaps idiosyncratic and counter to others at the time.”

Takayama’s defiant climb

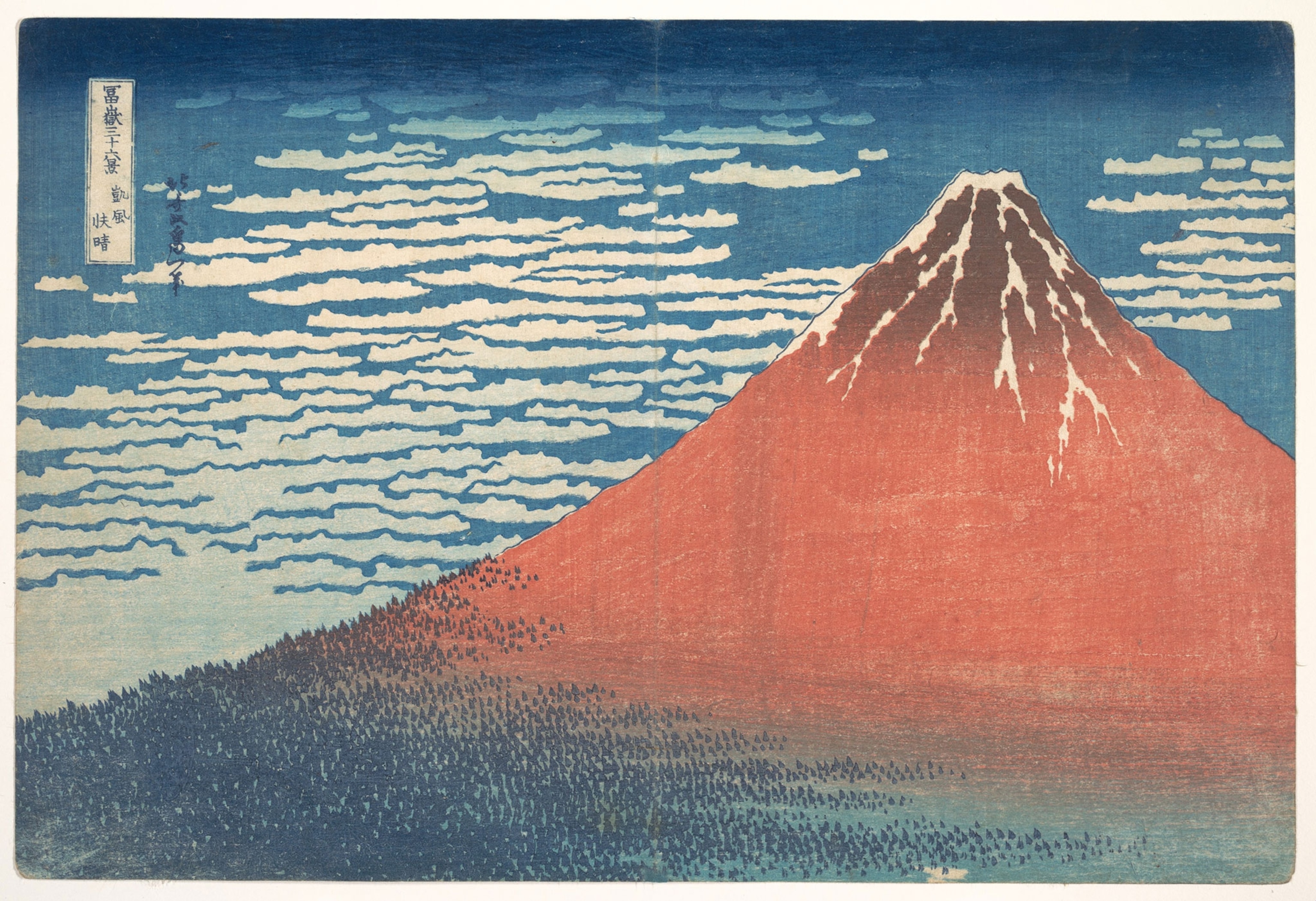

To this day, Mount Fuji rises in near-perfect symmetry from the plains of central Honshu in Japan, its cone stretching more than 12,000 feet into the sky. At dawn, light gathers slowly on its face, filtering through forests of cedar and pine and giving way to volcanic scree and fields of cinder. The air thins near the top, and even in summer, frost lingers in its folds.

Takayama began her climb at the edge of the season, in late October 1832. As documented in Takayama Tatsuko kankei shiryō, a compilation of historical records and sect documents related to Tatsu Takayama, she started from the Yoshida trailhead with five male companions—three fellow disciples, a porter, and Sanshi, the 68-year-old Fuji-kō priest who led the way. Sanshi’s guidance was unusual; most leaders of the time upheld the “no women” ban, but a small, vocal minority within the sect argued for granting women limited access to the mountain.

Takayama was 24 at the time. Her bangs were shaved, her posture careful. The records state she was “wrapped in a Benkei-style horned kimono” made of coarse, dark fabric, wide in the shoulders and tight at the waist.

They set out before dawn, when the air was brittle and biting. They wore straw sandals, their feet wrapped in layers of cotton tabi, socks designed for wear with the sandals. Each pilgrim carried little more than what could be tied at the waist: rice balls wrapped in cloth; ofuda, paper talismans stamped with the seal of their Fuji-kō congregation to ward off misfortune; and a strip of flint for fire.

By the fifth station, Chūgū, they stopped for the night. Once morning came, the world turned white: Snow had gathered overnight.

A Fuji-kō chronicle reproduced in Takayama Tatsuko kankei shiryō records say the group “traversed through thick snow,” the path forward sliding away beneath them, only to reappear, then vanish again. The wind tore at their clothes and gnawed at their faces.

Hours later, the summit gate, Torii, emerged through the mist. In Shinto practice, Torii marks the threshold between worlds, signaling the start of sacred ground.

There was no fanfare at the end of the ascent, only a young woman in men’s robes, head lowered at 12,000 feet. The Fuji-kō record marks it simply: “A woman born in the Year of the Dragon climbed the mountain in the Year of the Dragon.”

Sanshi recorded the ascent in a scroll preserved in Fuji-kō records kept by the Takayama family in Kamiochiai, Shinjuku. It’s one of the few surviving documents that attest to her groundbreaking climb.

What came after the climb

Although Takayama’s climb violated the “no-women rule,” historical records suggest she completed it without getting caught, likely moving quietly among a few other pilgrims and relying on the cover of an early-morning ascent and her disguise in men’s robes. Still, word of her feat spread slowly through Fuji-kō networks and local communities.

“The news of Tatsu’s ascent had in fact provoked the antipathy of local residents, some of whom attributed the natural disasters of the subsequent several years to it,” Miyazaki writes in her book.

Women remained prohibited from the mountain. Temple patrol logs, official records kept by Fuji-kō temples to document pilgrim activity, preserved in the historical compilation Nihon Sangaku Fujin-shi, describe several instances of women apprehended near Fuji’s mid-slopes.

Things wouldn’t start to change until 1867, 35 years after Takayama’s ascent, when Fanny Parkes, the wife of British diplomat Sir Harry Parkes, was hailed as the first woman to reach Fuji’s summit.

Parkes ascent gave non‑Japanese women a precedent for summiting Mount Fuji. Foreign women climbers were increasingly tolerated by trail officials in the late Edo years, even before the formal repeal of the ban.

More pilgrims followed, trails widened, and shelters appeared. And so it went: Japanese women climbed, were forgotten, and were buried in the margins of history. Takayama’s imprint faded.

(These 20 women were trailblazing explorers—why did history forget them?)

In 1872, four decades after Takayama’s ascent, the Meiji government lifted Japan’s ban on women entering sacred mountains. The reform was practical, not moral—a by‑product of modernization and government decree. And despite villagers and temple authorities long opposing women’s access, warning it would invite disaster, no large‑scale recorded protest marked the overturning of the ban.

More than a century later in the 1980s, Japanese historians Kōichirō Iwashina and Hiroshi Okada found Takayama again. In family archives, they uncovered a Fuji-kō scroll—frayed paper, faint ink, and a single line naming the woman who had climbed in the Year of the Dragon.

At the Saishō-ji temple, her grave sits small among many—its stone softened by rain and moss, its inscription worn to a whisper. Nothing marks her as the first or the boldest.

Mount Fuji still draws thousands of pilgrims each summer. Most will never know that the first woman to reach its summit did so in disguise, in snow, and without permission.