Fleeing violence in Venezuela, women migrants face callous indifference

Photos document the lives of migrant women in Lima, Peru as they strive to create safe spaces while longing for home.

From her apartment’s rooftop just as the sun sets, Rosa Marín curves her left index and thumb to form a circle in the air. Her two fingertips meet and create a little tunnel that seems to erase the rest of the landscape before her. With the improvised peephole, she frames a couple of distant tin-roofed shanties. For this brief moment she is no longer in Santa Anita, a working-class neighborhood east of downtown Lima, but rather back in her homeland some 2,600 miles away.

“My little Caracas,” says the Venezuelan migrant from her rooftop in Peru. “Whenever I go out of the room at night, I see this little spot that reminds me of home.”

Marín, 27, fled Venezuela in 2018 with her two children aboard a bus that took them on a week-long journey to start a new life in Peru, where she hoped to find stability and make enough money to help family members left behind. She envisioned Peru as a haven. But soon after settling in, she realized she didn’t feel safe nor welcome there.

“There’s a lot of harassment and xenophobia,” she says.

Marín is among the more than 6.1 million Venezuelans who have fled their country to escape a collapsed economy and healthcare system as well as increasingly deteriorating public services, which have resulted in frequent power outages and unreliable water supply.

Most Venezuelans settle in Colombia due to family ties and geographic proximity. The neighboring nation has received an estimated 1.84 million people. But Peru follows closely with nearly 1.30 million, and now has the second largest population of Venezuelan migrants in the world.

(Where else are millions of Venezuelans fleeing?)

This migration, dubbed by the UN as the largest external displacement crisis in Latin America’s recent history, also has shed light on the risks Venezuelan and other women migrants and refugees face across the region. Studies have found that they are at greater threat of becoming victims of sexual abuse and other sexist and xenophobic attacks while at work, at social events, or in public spaces.

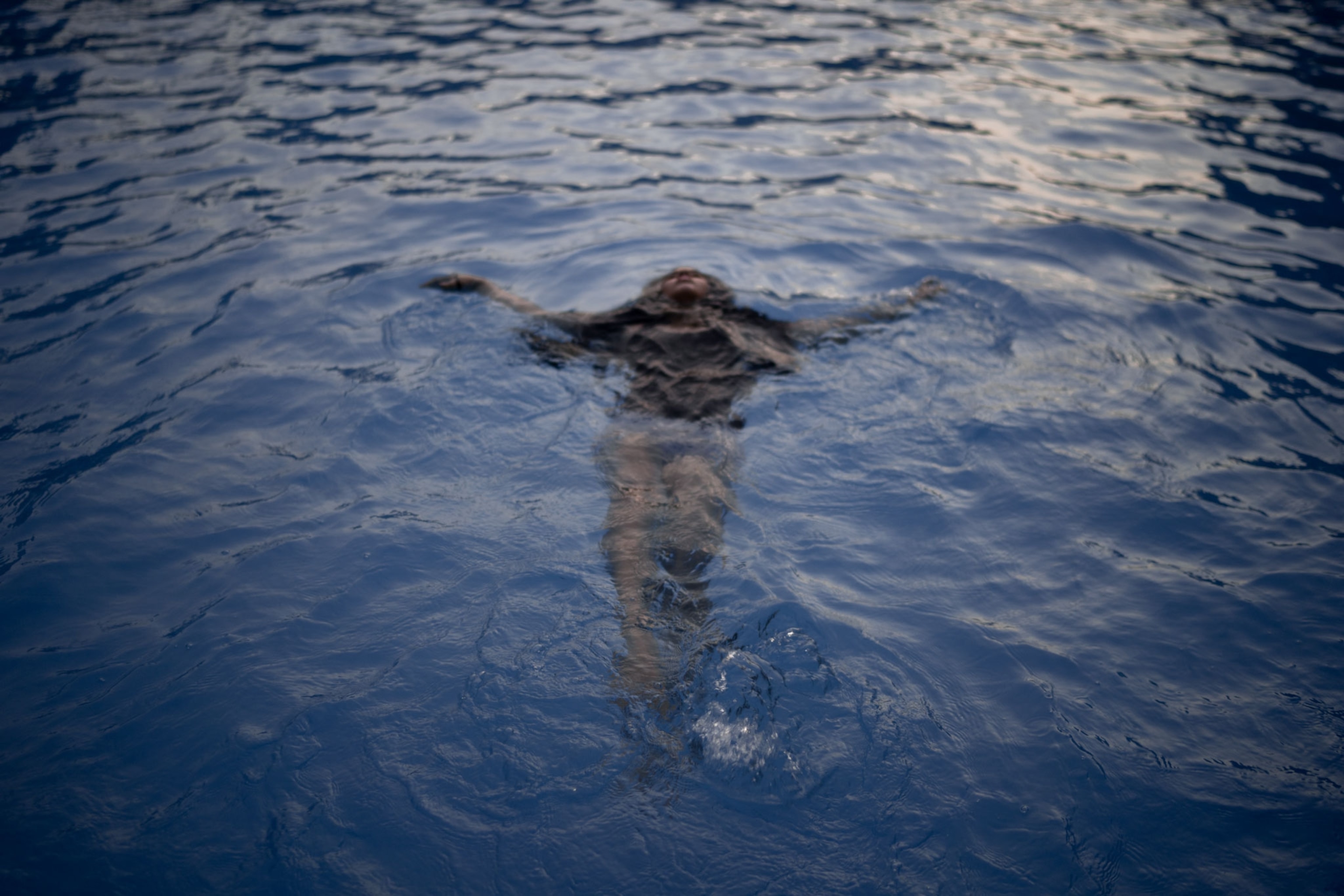

Many Venezuelan women in Peru, including Marín, have experienced these abuses. But rather than focusing on violence, which has become all too common, Peruvian photographer Daniela Rivera opted to document the safe spaces these women have created for themselves while navigating a hostile environment and yearning for the familiar.

“These women miss their families, their homes, having normal conversations with people, the warmth of the Caribbean,” says Rivera. “These tiny spaces they have built are their core and act as a protective shell.”

After living abroad for nearly four years, Rivera returned to Peru in 2019 to find a different country from the one she left behind. It was now common to hear the Venezuelan accent while buying groceries, using mass transit, or strolling the streets of Lima.

For six months, Rivera photographed eight Venezuelan women who chose Peru as their destination for a new life. They shared not only nationality, gender, and a history of violent encounters, but also a feeling of añoranza—deep sorrow for the absence, deprivation, or loss of someone or something loved. Rivera captures these complex yearnings in her images.

A study by academics Leda Pérez and Daniela Ugarte, from the Universidad del Pacifico in Lima, suggests that Venezuelan women in Peru face “a triple jeopardy” characterized by their nationality, gender, and condition as migrants. Because of this, they also risk engaging in informal, precarious, and underpaid jobs regardless of their level of education.

“Migrating like this, moved by the sense of survival because you have to leave to guarantee your well-being, already puts you in a vulnerable position from the start,” Pérez says, adding that starting anew in a country with “high levels of informality” in the economic sector can result in exploitation.

Yenifer, who prefers not to share her last name due to safety concerns, is 22 and mother of two, and entered the informal market despite having pursued a career as a dental technician. In 2019, she moved to Peru after the clients of the dental clinic where she worked in Venezuela started to pay with food instead of money.

Once in Lima, Yenifer began cleaning houses and selling food in kiosks. She often made less than minimum wage, suffered harassment and verbal abuses from her employers, and worked long shifts.

“You wake up early and it’s as if you were a robot. You go to work, you get home and nobody’s waiting for you, no one has made food for you,” Yenifer says. “The next day it’s the same. That’s the life of the Venezuelan migrant, you feel lonely all the time. It’s like a void.”

The Asociación Protección Población Vulnerable (APPV), a nongovernmental organization based in Peru, is striving to change this reality for women migrants. Founded by Martha Fernández, a Venezuelan human resources specialist who moved to Lima in 2008, APPV has created a support group for women migrants to connect, organize, and learn about their rights.

“We have received many cases of Venezuelan women whose rights have been violated. We want them to create spaces to stay together and support each other,” says Fernández. Since its creation in 2019, APPV has helped hundreds of women migrants from different backgrounds.

For Marín, adjusting to the new life became too difficult.

Last March, she boarded a bus again with her children and returned to Venezuela. The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru and the desire to see her family again was unbearable.

“I had been away for four years and my parents got sick while I was in Peru. I wanted to see them before something happens,” she says.

While she is relieved to be home, Marín doesn’t know if she will stay in Venezuela for long. But as she arrived in Caracas, her eldest son had a request: “No more adventures, Mom.”

Daniela Rivera Antara was born in Peru and raised between Lima and Australia. Her work focuses on gender with strong interests in displacement, inequality and identity. She is particularly interested in the role of memory, on trauma and belonging which are correlated to her experience as an immigrant and in being raised in a country with a complex post-conflict identity. See more of her work on her website or on Instagram.