Inside the murder plot that changed the course of history

A young Bosnian Serb had one plan to free his people from the monarchy of Austria-Hungary: kill Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the crown. The intricate assassination plan ended up setting off a chain of events that led to World War I.

The multinational capital of Bosnia

On the sunny morning of Sunday, June 28, 1914, the fates of two men collided with world-changing consequences in the city of Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nothing could have suggested their paths would ever cross. One of the two was Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a member of the monarchy and heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The other, 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip, came from a humble family. But despite his apparent powerlessness, Princip had one all-consuming mission: to strike a blow against the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, which had annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina six years prior. The young firebrand dreamed of shaking the monarchy to its core and stirring up Bosnian Slavs—whether Serbs, Croats, or Muslims— to rebel against their Austrian occupiers. Princip’s plan to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand was extremely audacious.

The heart of the matter

When he was born in 1863, Franz Ferdinand was third in line to the throne, and no one had expected him to become ruler of a powerful empire. Sickly with tuberculosis during his 20s and early 30s, it seemed more likely he would die young. He didn’t. Others, however, did not fare so well. The archduke’s cousin Rudolf, son of the aging Emperor Franz Josef and first in line to the throne, died of an apparent suicide in 1889. Then Franz Ferdinand’s father (Archduke Karl Ludwig), the emperor’s brother, who was next in line, died of typhoid fever in 1896. Suddenly, Franz Ferdinand was Franz Josef’s successor just as the Austro-Hungarian Empire began facing an existential crisis.

Emperor Franz Josef governed Austria and Hungary, splitting his empire into a dual monarchy. The two entities only had the monarch and the ministries of war, foreign affairs, and finance in common; they were otherwise a fragile unity. What kept that unity from unraveling was the political dominance that the Austrians and Magyars held over the other peoples of the empire. However, the rise of Slavic nationalism focused on Bohemia to the north and Serbia to the south, which threatened the fragile status quo. Bosnia and Herzegovina was becoming a tinderbox.

The roots of this volatile situation stretched back to 1878, when the Russian victory over the Ottoman Empire gained provinces in the Caucasus. Emboldened, Balkan states, including Serbia, declared war against the Ottomans in 1912, stripping the empire of nearly all its European territories.

The archduke's political vision

The Serbian leaders cherished the dream of a Greater Serbia that would include all the Slavs of the Balkans within its borders. However, this vision was severely shaken in 1908, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to international agreements, this region had been under Austro-Hungarian guardianship since 1878, though it was still formally Ottoman. It was on Bosnia and Herzegovina, with its mixed population of Muslims, Croats, and around 43 percent Orthodox Christian Serbs—like the Princip family—that Serbia’s nationalist ambitions became focused.

The people of Bosnia and Herzegovina considered the annexation an affront. Their discontent hardened into fervent nationalism, which in 1911 led to the founding of the Serbian nationalist society Unification or Death, better known as the Black Hand. This secret society was led by Dragutin Dimitrijević, also known as Apis, an army officer with a stellar military career behind him. The Black Hand’s goal was to unite Serbs by any means necessary.

In 1907 Princip, 13, left his native village of Obljaj for Sarajevo to study. Princip felt incensed by the annexation. His anger was fueled by the injustice he saw around him: the precarious living conditions of the community to which he belonged (six of his siblings died in infancy) and the lack of political rights. Like him, hundreds of young people opposed Austro-Hungarian colonial rule and longed to take action. Many were part of Young Bosnia, a network of groups promoting resistance against the authorities in Austria-Hungary.

Bogdan Žerajić the martyr

Direct action

To many members of Young Bosnia, violence seemed a legitimate response to the oppression they faced. One such act by a Young Bosnia member laid the groundwork for Princip. On June 15, 1910, 24-year-old Bogdan Žerajić fired five shots at the governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina on the Emperor’s Bridge over the Miljacka River in Sarajevo. But Žerajić missed, and with his last bullet, he took his own life. For Princip, Žerajić became an example of devotion to the liberation of Bosnia.

In Sarajevo, Princip immersed himself in various revolutionary literature (socialist, anarchist, nationalist) and attended student demonstrations against foreign rule.However, it seems he cut a rather lonely figure, always remaining an outsider. His increasing involvement with politics started to get him into trouble; in 1912, he took part in an anti-Austrian demonstration and was expelled from high school.That same year, Princip went to Belgrade, the Serbian capital, to complete his schooling. It was there that the young rebel chose to become an assassin.

Assassination avenue

By now Serbia was championing Balkan Pan-Slavism. Belgrade attracted young people who came there to study and also to express their political leanings. Many of these young people enlisted as irregular combatants in the Balkan Wars of 1912 (against the Ottomans) and 1913 (against Bulgaria),from which Serbia emerged with twice the population and territory.

Princip tried to enlist in 1912 but later claimed that he was rejected for health reasons. He went on to live a meager existence in Belgrade along with many other students and Bosnian ex-combatants from the past two wars. He told investigators later: “Wherever I went, people took me for a weakling ... and I pretended I was a weak person, which I was not.” Then the moment arrived for him to show his true colors.

The long shadow of Apis

In the course of the assassination, Dimitrijević was wounded. Three bullets remained lodged in his body. Nicknamed Apis, he became increasingly powerful within Serbia, founding the Serbian nationalist movement the Black Hand. His primary objective was to incorporate Bosnia and Herzegovina into Serbia. Apis helped foment guerrilla activity against the Austro-Hungarians. Princip received aid from the Black Hand, so it is likely that Apis directly participated in the plan to kill the archduke.

The plot

In March 1914, Princip read in the press that the archduke would travel to Sarajevo to inspect military maneuvers. His friend Nedeljko Čabrinović also read a similar newspaper clipping, which he showed to Princip. Čabrinović had reportedly stated that Princip suggested they assassinate Franz Ferdinand when he came to Sarajevo in June.

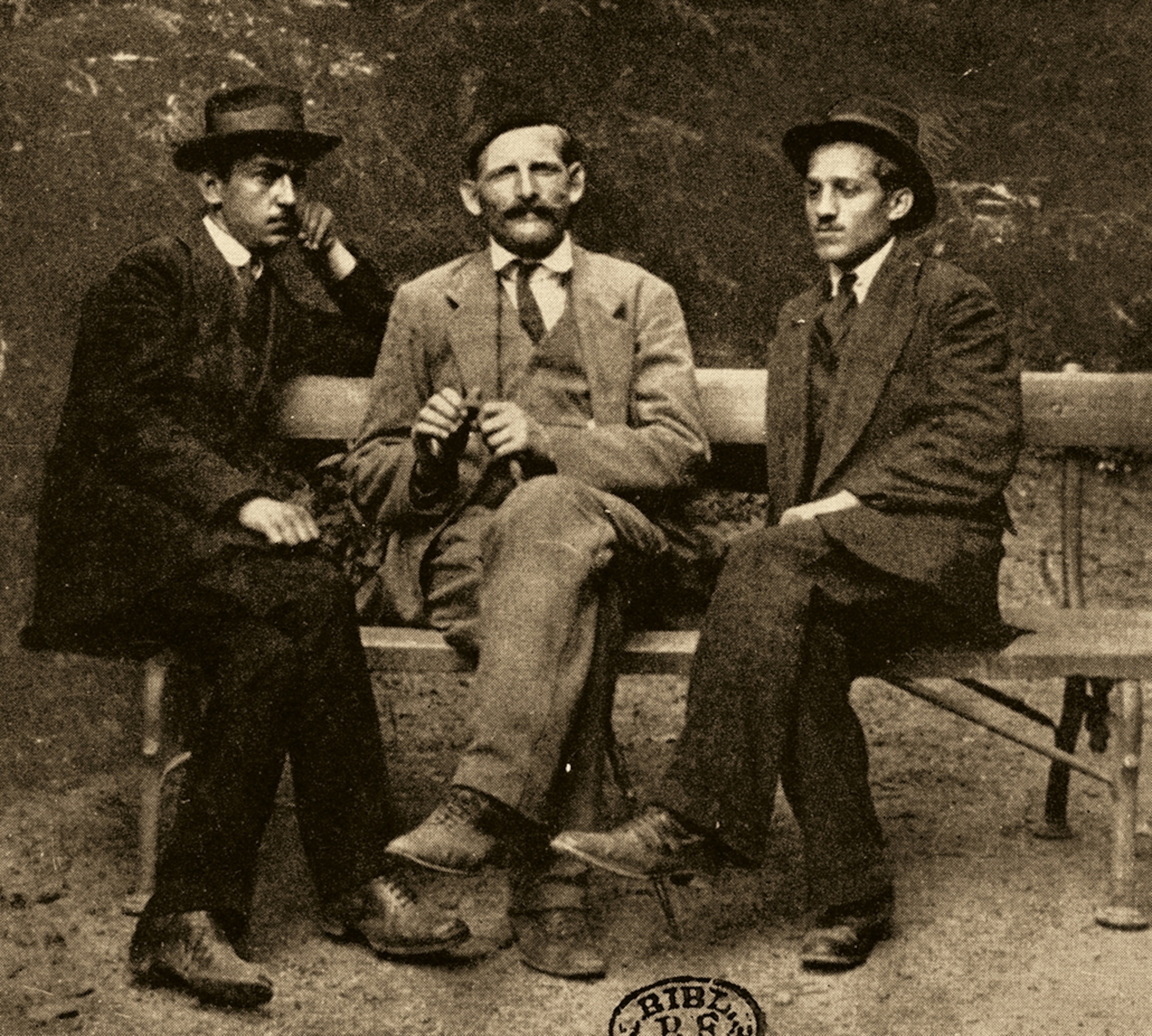

But time was short. Princip needed accomplices, weapons, and money in order to cross from Serbia into Bosnia without being picked up. He chose two Bosnian Serb comrades in Belgrade to help him: his initial co-plotter, Čabrinović, a typesetter, and Trifko Grabež, a student. Everything else would come via the Black Hand. But despite the support that the Black Hand provided, it was 19-year-old Princip who came up with the plot, amateurish as it was, and drove it forward. Astonishingly, it succeeded.

Princip got hold of the weapons through Milan Ciganović, a former Bosnian Serb combatant linked to the Black Hand. Ciganović, in turn, had gotten clearance from the Serbian commander Vojislav Tankosić, a major player in the Black Hand. Apis, the leader of the Black Hand, would later state that the Black Hand had been responsible for the entire plot. There were claims that Princip had been a member of the organization. However, in fact, his political goals were distinct. The Black Hand wanted the unification of the southern Slavs under Serb hegemony.But Princip envisioned a state that would welcome Serbs, Muslims, and Croats on an equal footing.

Ciganović provided the three would-be assassins with six bombs and four pistols. He took them to a forest, where he taught them how to shoot. He also provided enough money to pay for their trip to Sarajevo. The young men set out from Belgrade on May 28. Thanks to maneuvers by the Black Hand, the Serb customs officials looked the other way as the group crossed the Drina River into Bosnia. When they arrived on the western bank, Bosnian Serbs helped them on their journey southwest to the city of Tuzla. From there, they continued by rail, arriving in Sarajevo on June 4.

Previously, Princip had written to Danilo Ilić, who lived in Sarajevo and was a member of Young Bosnia, asking him to find more accomplices for the attack. In May Ilić recruited three more people: a Bosnian Muslim carpenter in his mid-20s, Muhamed Mehmedbašić, and two students—Vaso Čubrilović, age 17, and Cvjetko Popović, 18. Mehmedbašić had already been involved in a failed Black Hand plot to kill Gen. Oskar Potiorek, the governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

A linguistic muddle and a lucky shot

On June 14 Ilić collected the weapons, which Princip had entrusted to a businessman from Tuzla. However, as time went on, Ilić had doubts about the attack. He wondered if it might unleash even more suffering for the Serbs under Austro-Hungarian rule. Ilić discussed with Princip whether political action might be more effective than terrorism. Ultimately, he was persuaded to go ahead with the plan for the sake of his friend.

(World War I soldiers created underground art in the trenches)

The attack

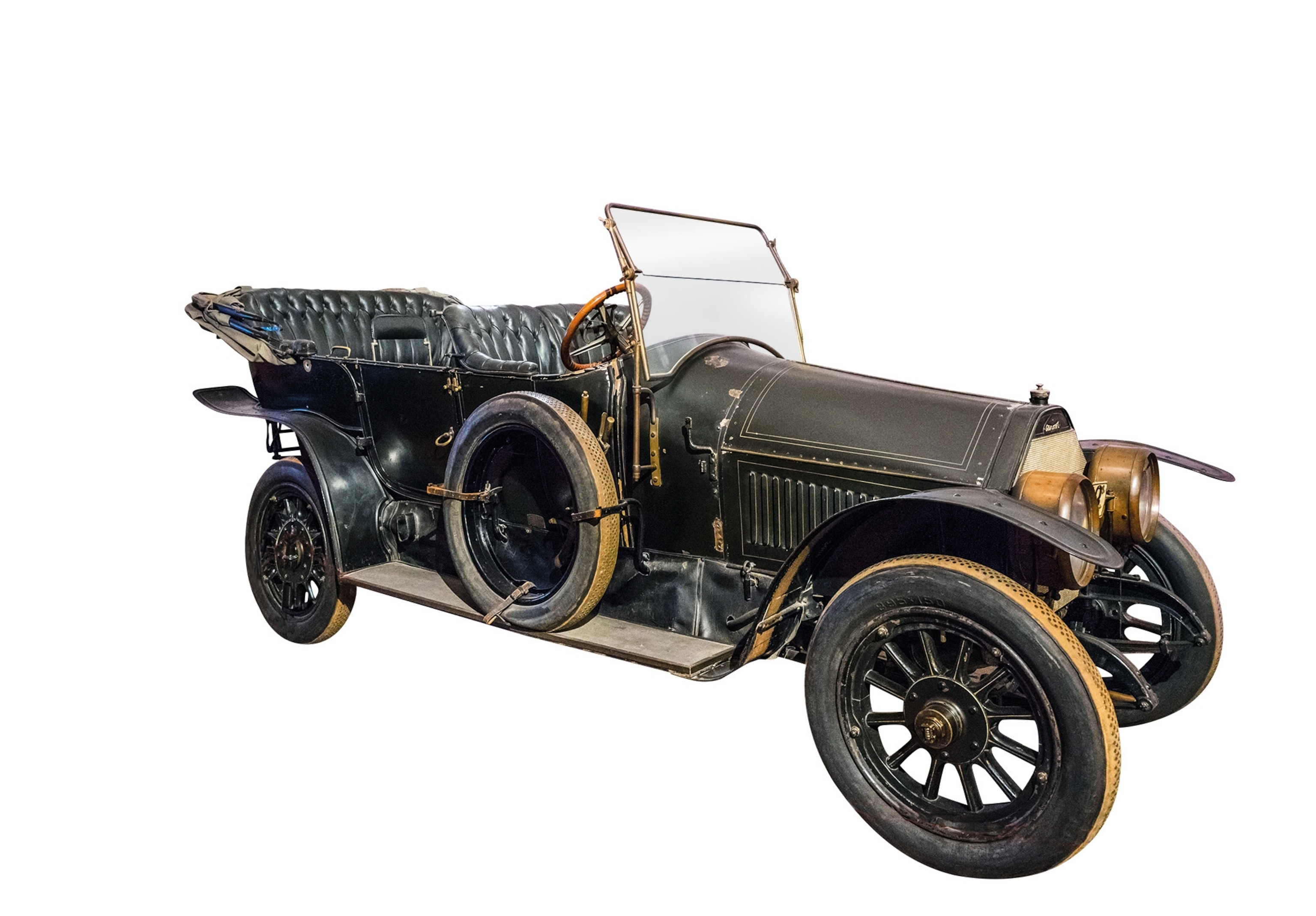

On June 28 Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Countess Sophie Chotek, Duchess of Hohenberg, were scheduled to attend a reception at Sarajevo’s city hall and visit the local museum. They arrived in Sarajevo from Ilidža, a nearby spa town, and were scheduled to travel in their motorcade on Appel Quay to city hall for a reception. This wide avenue is next to the Miljacka River, which divides Sarajevo in two. Along the route, six armed men—Mehmedbašić, Čubrilović, Čabrinović, Popović, Princip, and Grabež—mingled with the crowd that had turned out to see the royal couple as they passed along the Appel Quay. To engineer a sense of closeness between the crown and the Bosnian people, the army had not cordoned off the route. Additionally, the local authorities had mobilized only about 150 police officers. It was a risky move, and the possibility of an attack hung in the air. That threat had prompted the countess to accompany her husband to Bosnia in the first place.

With luck on their side

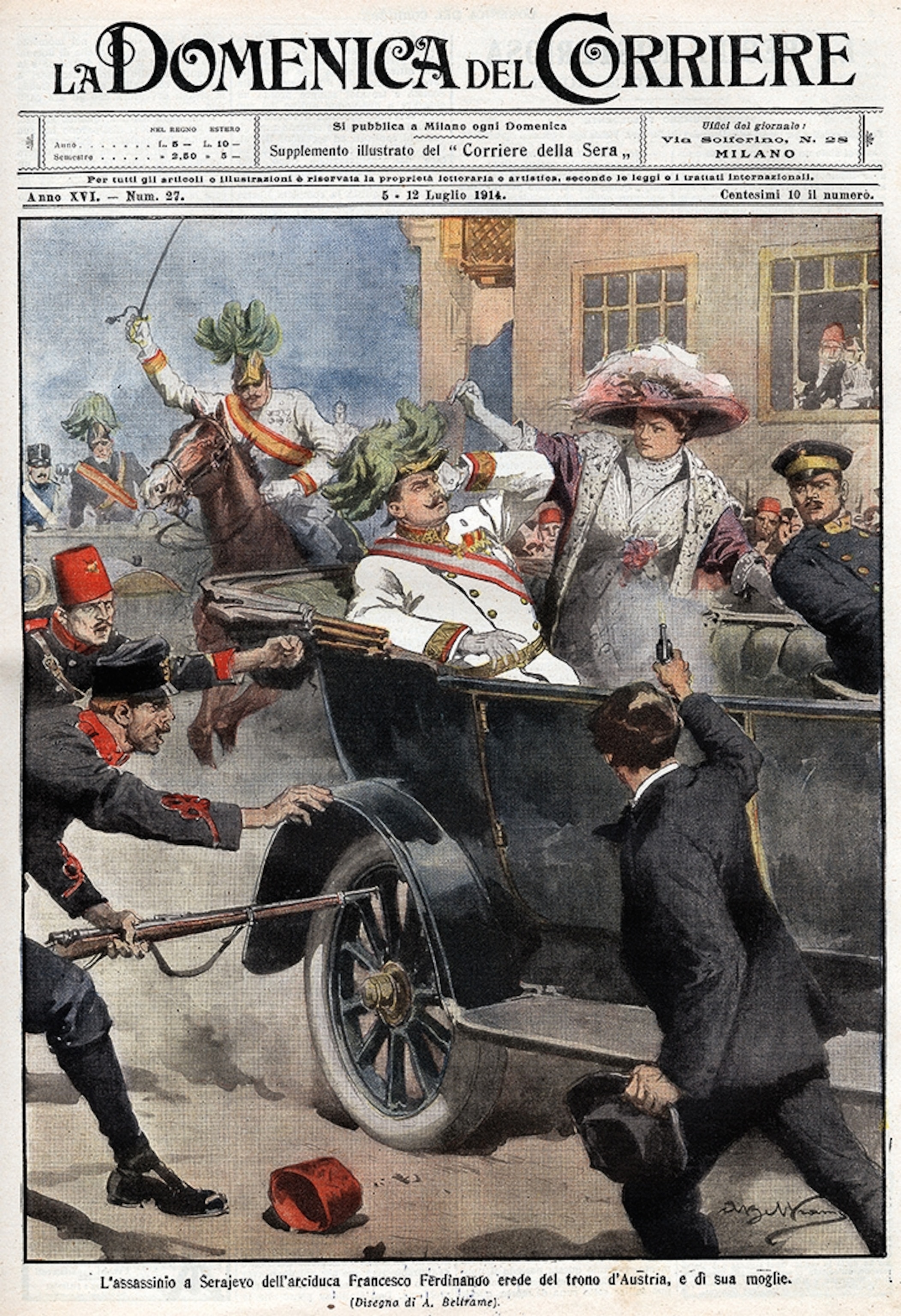

The motorcade of six vehicles passed in front of Mehmedbašić, who stood primed and ready with his bomb. But he didn’t detonate it as planned because a police officer was reportedly in the vicinity. Čabrinović, the next to get a chance, hurled his bomb at the third car in the motorcade, where the archduke was traveling. Franz Ferdinand’s helmet, topped with green-dyed vulture feathers, made a useful target. But the bomb ricocheted off the canopy at the back of the car and fell to the ground, exploding as the next vehicle passed by, injuring several people. It was 10:10 a.m. The motorcade sped up, making it impossible for the other four men to get a decent aim. Čabrinović tried to escape by jumping into the Miljacka River. Like all the terrorists, he was carrying cyanide, which he then took in a bid to kill himself rather than be captured. But the poison only burned his mouth and throat, and Čabrinović was caught and arrested.

Despite the attempt on his life, the archduke tried to appear unruffled.The couple attended a reception at the city hall. However, a decision was made to modify their route. The archduke and his wife didn’t enter the city to go to the museum as originally planned. Instead, they drove along the Appel Quay to the hospital and visited those wounded in the attack. However, the change of plan to divert to the hospital was not properly communicated to the archduke’s driver. Once they reached Franz Josef Street, the driver turned right.

On the corner at Appel Quay, next to the Moritz Schiller café, Princip stood quietly, waiting for the motorcade to pass. Military governor Oskar Potiorek, also in the car with the royal couple, saw the mistake in the route and yelled at the driver to back up. But putting the car into reverse was not easy: It involved first reversing the drive belts, a procedure that took some time. Princip saw his chance and fired twice, one shot at the archduke and another at Potiorek. The first bullet hit Sophie in the abdomen. The second bullet hit Ferdinand in the neck, severing a jugular. Those around him did not realize what happened at first, as the blood was pumping out under the tunic of his uniform. Franz Ferdinand and the countess were mortally wounded, dying within minutes. Princip swallowed his cyanide and then aimed the gun at his head.But the weapon was snatched from his hand before he could pull the trigger, and the cyanide would prove not to be fatal.

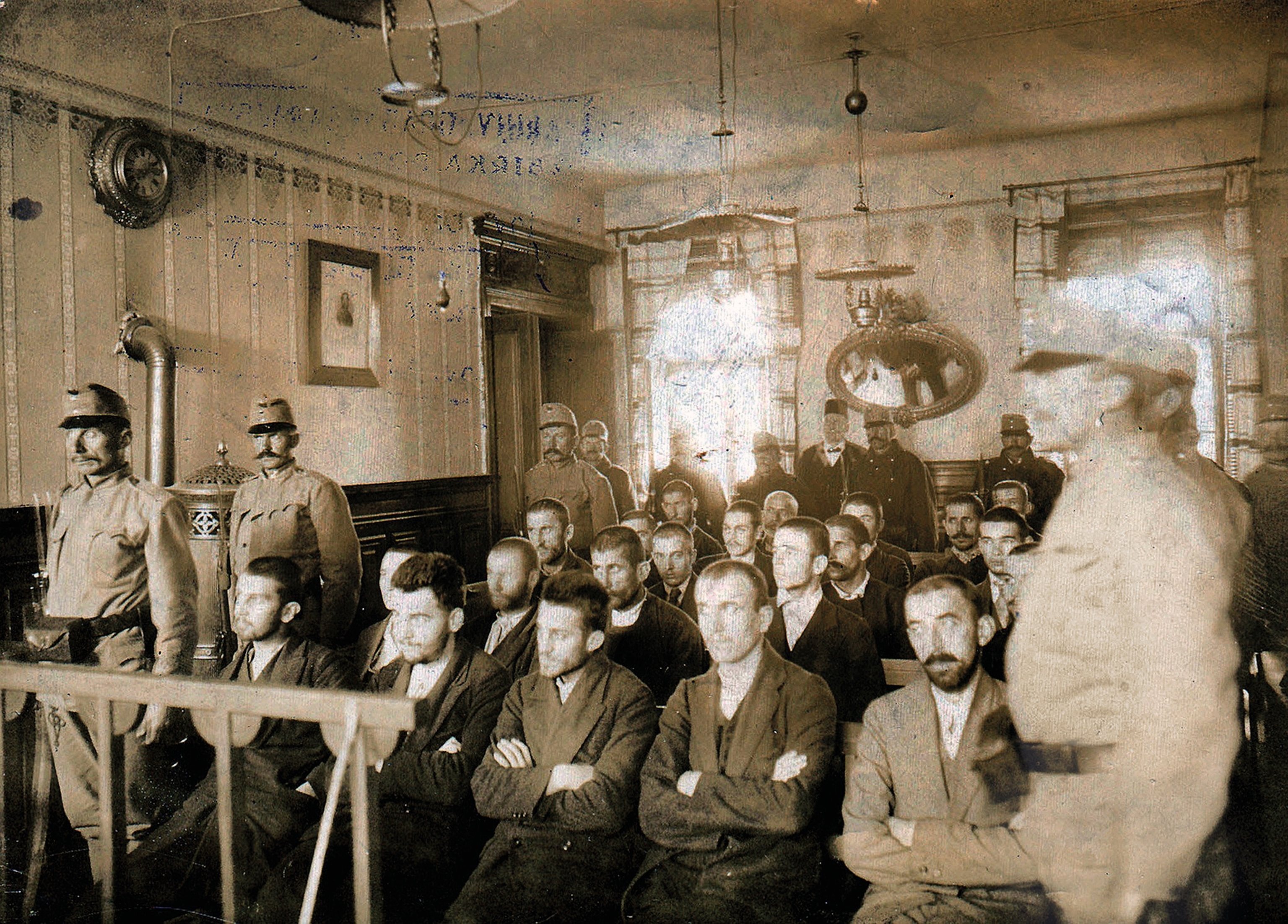

A chapel of remembrance

Mehmedbašić managed to flee to Montenegro, but the other five participants in the attack and those who had helped them in Bosnia were all arrested. Ilić was hanged, while the others were spared capital punishment due to their age. Čabrinović and Princip later died in prison from tuberculosis. The incident gave Austria-Hungary an excuse to attack Serbia, causing a shift in alliances among the European powers. A chain reaction was started, propelling Europe into the First World War, the most extensive conflict the world had experienced up until that time.

How much did Serbia know?

The conclusion

The investigations by the Austrians could not prove that the Serbian government was involved in the assassination or knew much about the plan in any detail. The Austrian investigations also failed to clarify the precise role that the Black Hand had played, although they did identify Ciganović and Tankosić as accomplices.