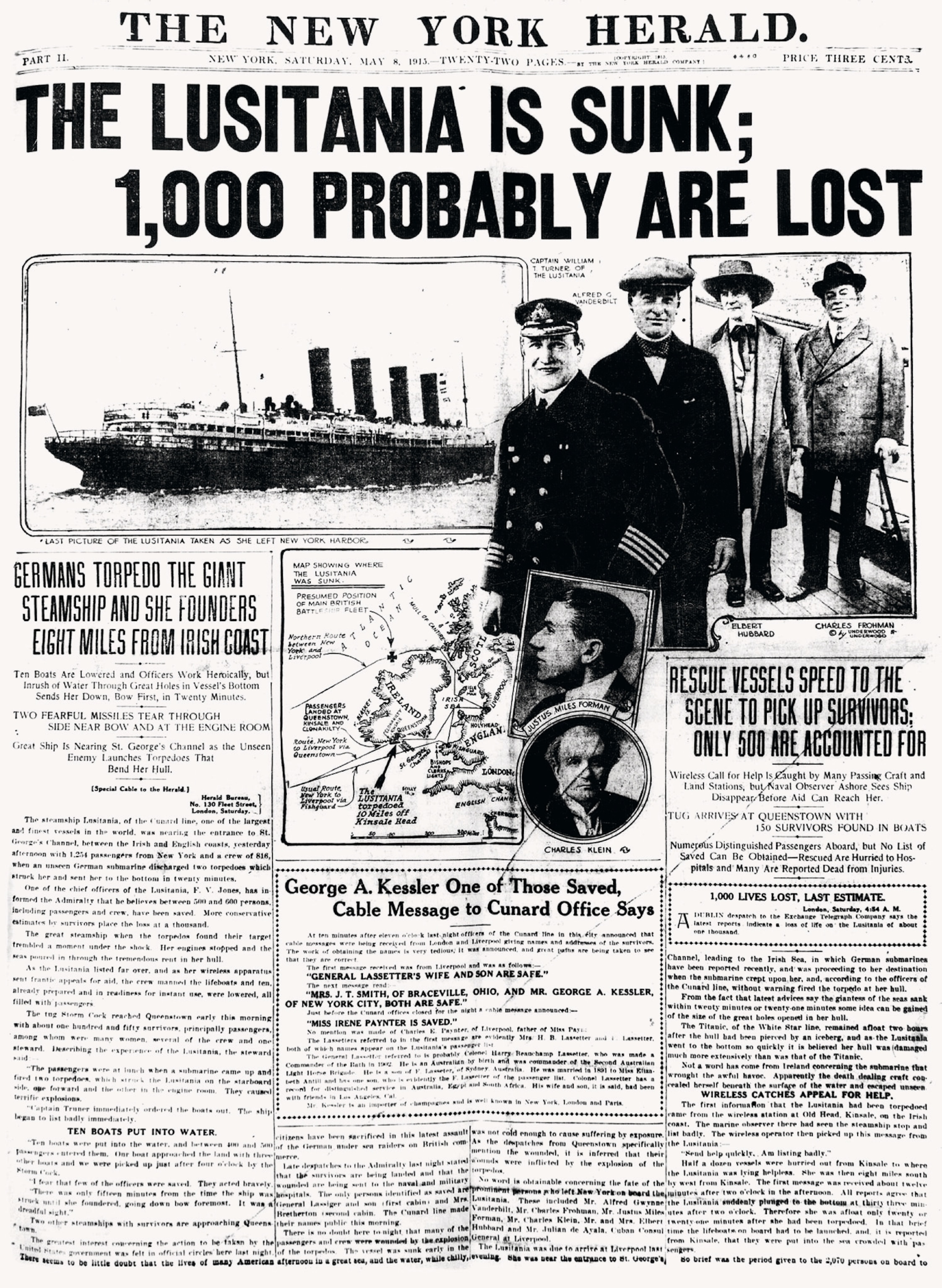

How one torpedo sank the mighty Lusitania

The British ocean liner was torpedoed by the Germans during World War I, killing over one thousand people and changing the tide of war. But controversy still surrounds the disaster as some questions are left unanswered.

Built between 1904 and 1906, R.M.S. Lusitania measured a whopping 787 feet in length and could accommodate over 2,000 passengers and 800 crew members. It soon became the flagship of its operator, the Cunard Line, and for a time was distinguished as being the largest passenger ship in the world. Both the vessel’s luxurious design and fate are often compared to those of R.M.S. Titanic, launched in 1912 by Cunard’s main rival, the White Star Line. Despite their grandeur, both ships met tragic ends, though under markedly different circumstances. While the Titanic sank after hitting an iceberg in 1912, the Lusitania was torpedoed by a German U-boat during the First World War.

Germany under blockade

Since the onset of WWI in 1914, Germany had faced a comprehensive naval blockade imposed by the British Navy that cut their flow of war supplies, food, and fuel. The Germans retaliated by using their submarine fleet, the Unterseeboote, or U-boats, to target neutral ships that were supplying the Allies. They hoped to starve Britain before its blockade defeated them. The Lusitania was a prime target. The passenger liner regularly transported food and supplies from the United States to Britain, but on that fateful day it may have also had on board bullets, fuses, shells, and munitions. Although the crew and Germans were likely aware of that, the cargo was probably unknown to the passengers.

(Wreck of fabled WWI German U-boat found off Virginia)

In February 1915, under pressure from his naval officers, German emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II authorized a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare to attack British merchant ships. Until then, enemy merchant ships that were carrying contraband could be sunk only if they had first been searched and evacuated. But Germany argued that the risks to U-boat crews made surface inspections impossible. This new policy placed the Lusitania in the line of fire. In March 1915, Captain William Turner replaced Captain Daniel Dow as master of the Lusitania. It has been reported that Dow took sick leave and had been showing signs of stress. Some speculate that it was because of having to operate through a war zone. On May 1 of that year, under Turner’s command, the Lusitania departed New York for Liverpool on what would become its 202nd and final transatlantic voyage.

The departure was marked by unusual anxiety. Days earlier, the Imperial German Embassy in the U.S. had placed an advertisement in American newspapers, declaring that passengers on English vessels sailed “at their own risk.”

The Lusitania was seen as invulnerable. The passenger liner was said to be faster than any German submarine and could easily outrun them. Rumor also had it that in the event of an attack, the British Navy would provide an escort or that the ship would remain afloat long enough for all passengers to be evacuated safely. The number of lifeboats onboard had been increased since the Titanic’s sinking, reinforcing a sense of security.

(What we’ve learned—and lost—since the Titanic wreck was found)

Precautions

Despite German warnings, the Lusitania set sail as expected. The voyage started with warm weather and smooth seas. On May 6, upon entering the newly declared maritime war zone, passengers were instructed to close the portholes, the ship’s lights were turned off, and lifeboats were prepared as a precaution. That night’s concert was interrupted by an announcement from Captain Turner: German submarines had been sighted in the waters ahead. Turner assured them there was no cause for alarm, reiterating that the Lusitania was faster than any German submarine, and that they would be protected by the British Royal Navy the following day. One of the ship’s four boilers had been shut down to conserve coal, but it still should have been able to outrun any German submarine. Despite Turner’s efforts to reassure them, many passengers, feeling uneasy, chose to sleep on deck.

At 6 a.m. on May 7, a thick fog settled over the ship. Captain Turner ordered the vessel to slow down and had the foghorn sounded every minute, unsettling the passengers. As the weather cleared up later in the morning and the Irish coast became visible from the deck, passengers began to relax. But beneath the surface, the threat was already closing in on the Lusitania.

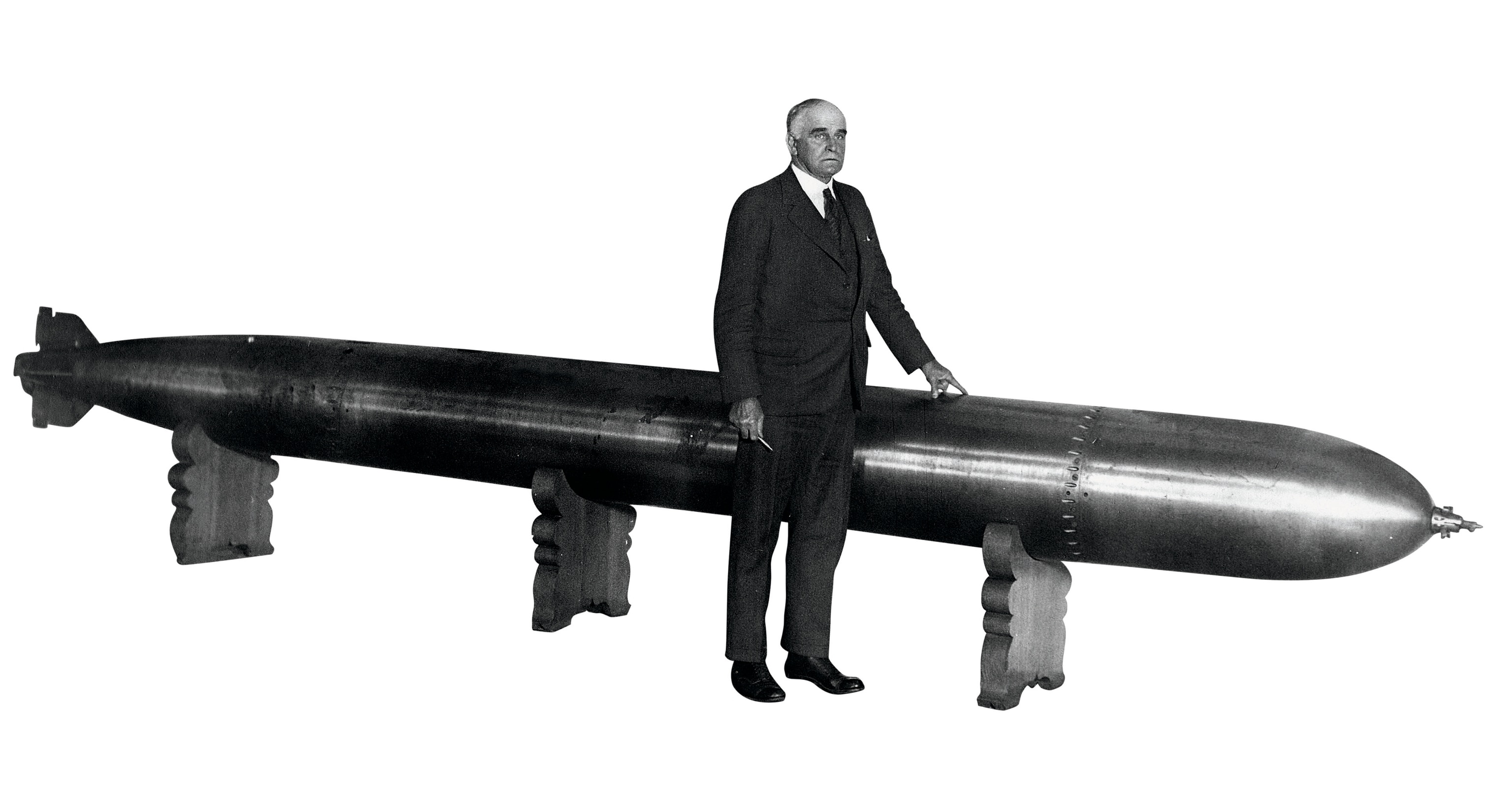

The attack

A German submarine, the U-20, had spotted the ship and,thanks to improved visibility, positioned itself just 2,300 feet away. At 10 minutes past two in the afternoon, it fired a torpedo. Albert Bestic, Lusitania’s third officer, saw the trail of bubbles left by the projectile as it raced toward the ship.“This is the approach of death,” he thought. The impact triggered a violent explosion. Bermudian traveler Mary Beatrice Lobb, who is said to have been sitting and reading on the deck, reportedly stated that there was a terrific booming explosion, followed by a torrent of water and coal dust. Moments after the initial impact, a second, even more powerful explosion rocked the vessel, accelerating its fatal descent. Some theories blamed coal dust and/or boiler rupture; others pointed to hidden munitions, a claim Germany used to justify the attack. Recent evidence shows that the ship may well have been carrying high explosives.

German aggression

Whatever the source, the damage was catastrophic. The ship began to list severely, and Captain Turner, realizing the extent of the destruction, attempted to steer for the coast. But the rudder wouldn’t respond, and the engines couldn’t be slowed. Turner gave the order to evacuate, but there was little way of escaping. Some of the lifeboats were inaccessible because of the heavy starboard list, while others were destroyed after crashing into the water. The Lusitania sank in a mere 18 minutes, preventing most lifeboats from being launched. Of the 1,959 people on board, an estimated 792 survived. Among the dead were 94 children, 35 of them infants.

Commotion

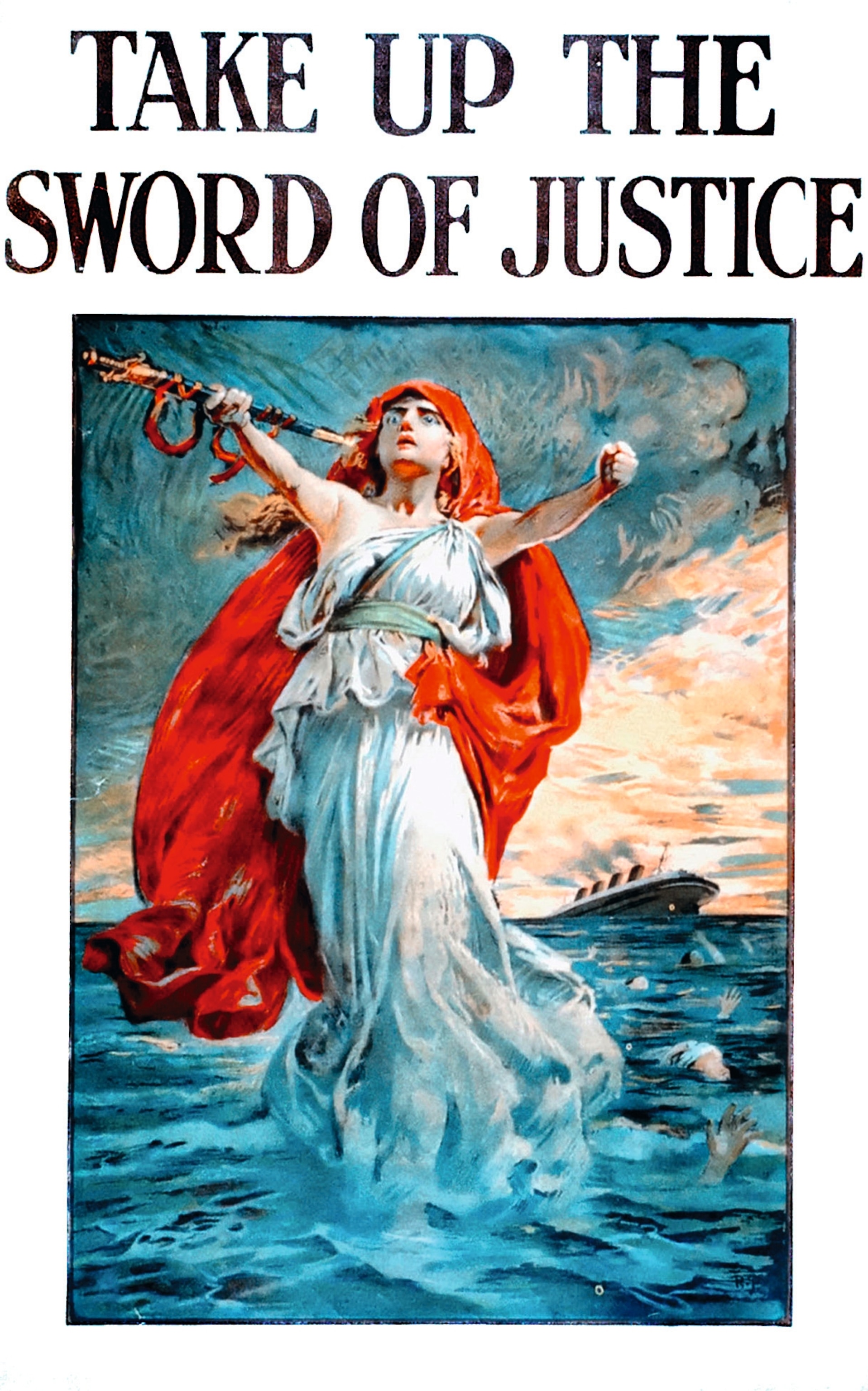

German Crown Prince Wilhelm reported to his father, Kaiser Wilhelm II, that there was “great joy” among army officials at his headquarters in northern France. Pro-imperial newspapers celebrated the attack as a strategic success, claiming Germany’s naval war was more humane than Britain’s, and that the British naval blockade condemned the entire German population to starvation, Germany had only attacked those who ventured to cross hostile waters.

(Inside the murder plot that changed the course of history)

The Allies saw things very differently. The New York Times headline on May 8, 1915, read: “Press Calls Sinking of The Lusitania Murder; Editorials in New York Newspapers Agree Torpedoing Was Crime Against Civilization.” In British cities such as London and Liverpool, crowds expressed their anger by ransacking German-owned stores. Among the Allied ranks, the disaster reinforced the conviction that the Germans were brutish, with no respect for international law, which fueled the Allies’ determination to defeat Germany in defense of Western civilization. No longer seen as a distant European affair, the tragedy marked a decisive shift toward U.S. intervention in the Great War, hastening the conflict’s global escalation.

Loose ends in the Lusitania tragedy

The sinking of the flagship of the British civilian fleet sparked long-standing debate. Controversies continue to surround key issues such as the nature of the war cargo on board and the actions of the ship’s captain.

1) The ammunition charge and the mystery of the second explosion

Along with food and supplies, the Lusitania was carrying 4,200 cases of rifle cartridges, cases of shrapnel shells, and aluminum powder used to produce explosives. Germany claimed that the ammunition triggered the fatal second explosion. The British initially denied that the ship was carrying ammunition, before later admitting that it was, but only small arms and empty artillery shell casings. However, secret British defense files released in 2014 revealed serious concerns surrounding the ship’s 1982 salvage operation, with warnings given to divers of the danger of high-explosive shells. Numerous surveys have since been conducted at the wreck, but no explosives have ever been found.

2) The British government faced conspiracy theories over perceived failure to protect the Lusitania

The lack of protection for the Lusitania near British waters led to speculation that the British government deliberately risked a German attack to draw the U.S. into the war. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote a letter to the British Board of Trade a week before the tragedy, saying “it is most important to attract neutral shipping to our shores, in the hope of embroiling the United States with Germany ... we want the traffic—the more the better; and if some get into trouble, better still.” The negligence may be better explained by British naval forces being tied up in the Gallipoli campaign and the belief that Lusitania’s speed would keep it safe.

3) Was it easy for a torpedo to sink an ocean liner?

At the time, submarines had to be within 1,600 to 1,000 feet of their targets to launch a successful torpedo strike, which is why many believed that the Lusitania’s speed would allow it to escape danger once an enemy submarine was spotted. Ironically, it was a change of course ordered by Captain Turner that brought the ship within range of the U-boat. The torpedo’s impact on the starboard side proved critical. If it had struck another part of the ship, it may not have affected the nearby boiler room, and the second explosion may not have occurred. The fatal, perfectly aimed hit was also due to the German captain’s belief that the Lusitania was traveling four knots faster than it actually was.

4) Lusitania captain criticized for saving his own life

After doing everything within his power to avert disaster, Captain Turner remained on the bridge with his life jacket, refusing to abandon ship until the water had risen to that level. As the ship sank he washed off the bridge and spent three hours in the sea before being pulled into a lifeboat. Despite this, public opinion condemned him as a coward for surviving the sinking. The Admiralty sought to place blame on him; passengers who had survived shouted insults at him in the streets; and he received anonymous letters that mocked his decision not to go down with his ship. His estranged wife left for Australia with their children. Yet Cunard retained him as captain, and in 1917 he survived another torpedo attack that sank his ship in the Mediterranean.