The discovery of DNA started with this overlooked scientist

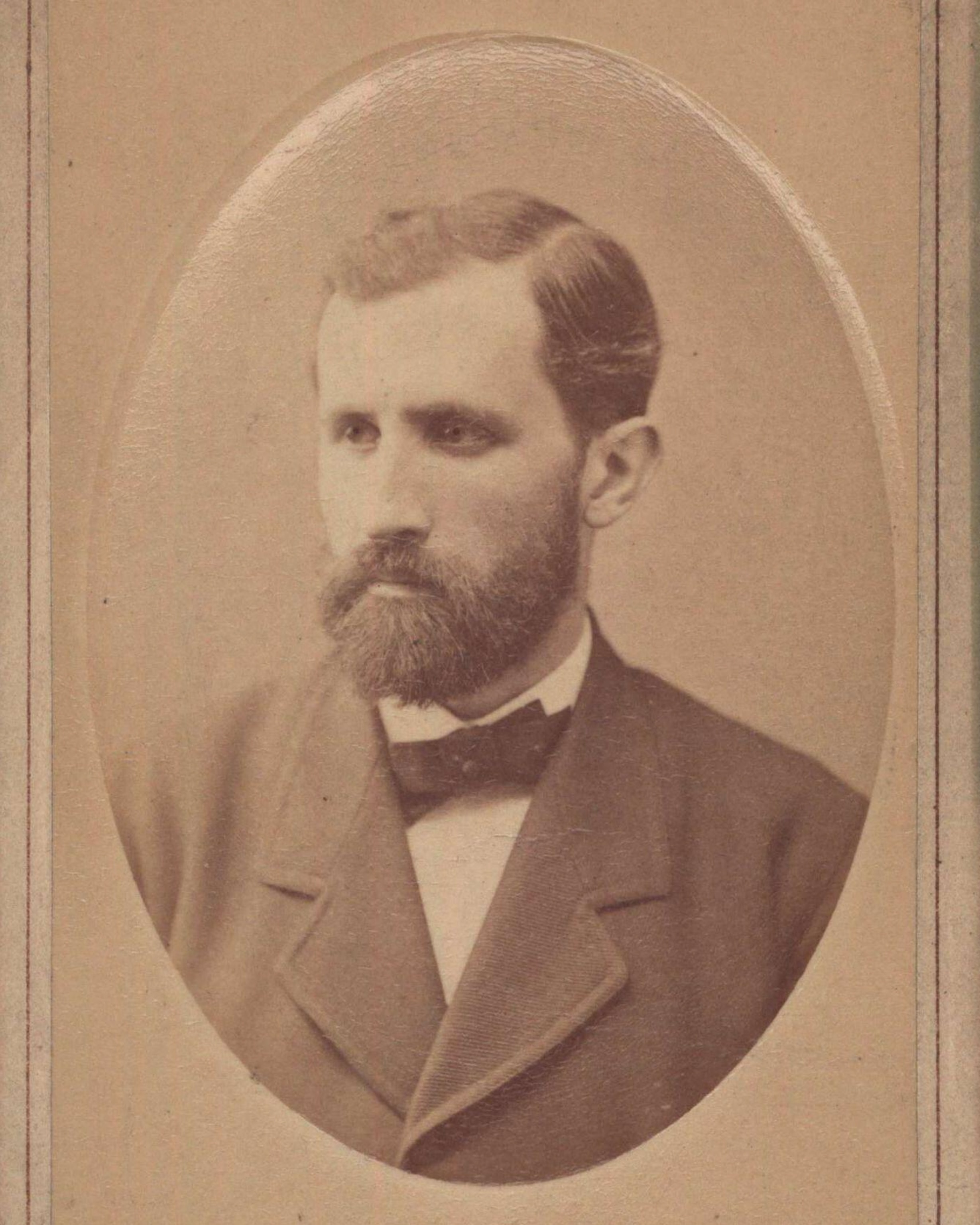

In 1869, Swiss scientist Friedrich Miescher isolated a mysterious substance from cell nuclei—an overlooked finding that would later reshape biology and our understanding of life itself.

When James Watson and Francis Crick uncovered the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953, they didn’t just solve a biological puzzle—they released the hidden code that governs life itself. But the landmark discovery was only possible because of earlier remarkable findings.

Eighty years before, the research of one Swiss biochemist identified an essential foundation for DNA: nucleic acid. While experimenting with pus cells from used bandages, scientist Friedrich Miescher discovered this key component of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. Today, nucleic acid is considered the fourth main biomolecule alongside lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins. Unlike Mendel or Darwin, few remember Miescher’s impact because his discovery was decades ahead of its time, lacking context regarding its role in heredity.

However, his work is critical to our understanding of the world around us. “If you're thinking about DNA, it starts with Miescher,” says science historian Neeraja Sankaran.

So, who exactly was the forgotten scientist Friedrich Miescher? Here’s how a 19th-century scientist few have heard of discovered a building block of DNA in human cells.

Before the DNA helix

Miescher was born in 1844 in Basel, Switzerland, into a family of respected doctors, which sparked his interest in science from a young age. He studied medicine, but his hearing loss from a childhood bout with typhus made him worried he wouldn’t be a good physician, says molecular biologist Kersten Hall.

In 1868, Miescher moved to Tübingen, Germany, to work in a lab under the scientist who founded biochemistry and molecular biology—Felix Hoppe-Seyler.

While working at Tübingen University in 1869, Miescher studied white blood cells by collecting pus in used hospital bandages. Antiseptics weren’t widely available yet, so wounds regularly got infected, explains molecular biologist Ralf Dahm.

Miescher wanted “to understand life at the chemical level, so understanding how molecules make life effectively; an unbelievably ambitious goal he had,” Dahm says. White blood cells were an ideal starting point because “they're not embedded in a tissue, and because they can move, unlike most other cells.”

As Miescher began studying the white blood cells, he spotted the three known biomolecules at the time—lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins. “Miescher found a substance which was enigmatic to him because it didn't have the properties of the other substances,” says Dahm.

He tried digesting the mysterious substance with pepsin to break down proteins, staining it with iodine to identify carbohydrates, and washing it with alcohol and ether to dissolve the lipids. But it was all to no avail. He called the new substance "nuclein” because he separated it from the nuclei of the white blood cells, which houses our DNA.

(Everything you need to know about the building block of life.)

Miescher knew he had made a monumental discovery, says Dahm, and he wanted to make sure everyone knew about it.

No one wants to read about pus

Before Miescher could publish his work, he experienced a series of unfortunate events. First was that he had to wait two years to publish his paper as Hoppe-Seyler verified his work. This was done out of caution, as one of the scientist’s previous students had wrongly claimed to find a new substance that ended up being only a “chemical mirage,” Hall says.

In 1871, Miescher published his findings in a paper titled On the Chemical Composition of Pus Cells. “It's not a title that has you on the edge of your seat,” Hall says.

If the name alone didn’t stop people from reading his paper, Miescher also buried the significance of his findings until page 19 of the 20-page paper. “You have to wade through a lot of excruciatingly boring chemical analysis of cells you may not care about in the least to discover that he has just revolutionized biology,” Dahm says.

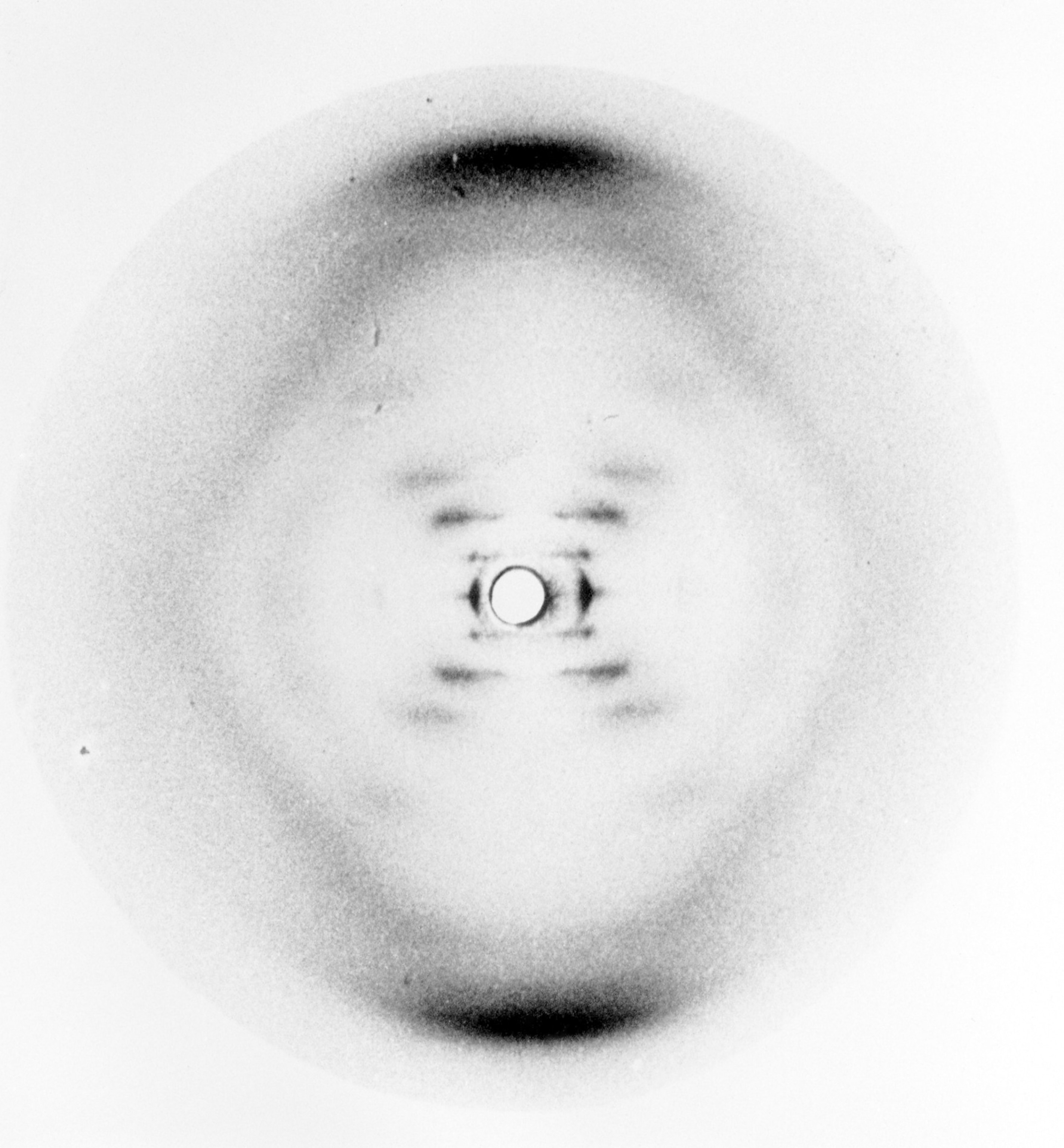

He also didn’t have anything compelling to show people to demonstrate his findings. “DNA at Miescher’s time was an abstract concept,” Dahm says. “It was a molecule with properties somewhere in the cell.”

“There’s this letter he wrote where he said, 'For years now I have had to get used to the feeling that my work has an urgency, and I go to bed feeling like a schoolboy who has not studied for his lessons.' It's just that sense of things left undone.”

In 1872, a year after his paper was finally published, Miescher began teaching at the University of Basel. His students regarded him as an extremely dedicated scientist, almost to a fault. One of his students, Fritz Suter, said that Miescher nearly missed his own wedding because he was in the lab working.

The road of research that led to DNA

In 1889, 20 years after Miescher’s initial finding, his student Richard Altmann coined the term “nucleic acid” to describe nuclein. “I think it was a little bit of an intellectual land grab on the part of the student to usurp the mentor,” says Hall.

By coming up with a different name for the same DNA molecule, Altmann made a convincing argument that Miescher’s nuclein wasn’t the same thing as his own nucleic acid. This downplayed Miescher’s findings considerably. “And Altmann’s name stuck,” along with the term nucleic acid, Hall adds.

Hall’s upcoming book on Miescher, co-authored with Dahm, reveals that Miescher, not famed Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger, was the first person to suggest how variation in biological traits might show up in a molecule, says Hall. “To the best of my knowledge this is the first time that anyone had proposed this.”

Decades later, in 1953, Watson and Crick would give a structure to the DNA molecule Miescher found in the form of the iconic double helix, says Hall.

Watson and Crick had more visible evidence of their discovery than Miescher did. “The double helix is, at least to me, a very beautiful structure aesthetically, totally independent of its function,” Dahm adds. “It makes it tangible.”

Miescher’s legacy

Miescher died in 1895 of tuberculosis at age 51 and even now his work is rarely acknowledged by the scientific community.

Miescher also described himself as Sisyphus from the Greek myth, doomed to endlessly push a boulder up the hill, Hall adds.

But Hall argues that is an important part of Miescher’s legacy. “[Science] is like rolling the boulder up the hill, but it’s a team sport,” Hall says. “I'm very keen to get away from all these stories of lone geniuses and eureka moments.”

It took a series of intricately woven threads for scientists to arrive at the full significance of Miescher’s findings, Sankaran says. Miescher had “one very important thread.”