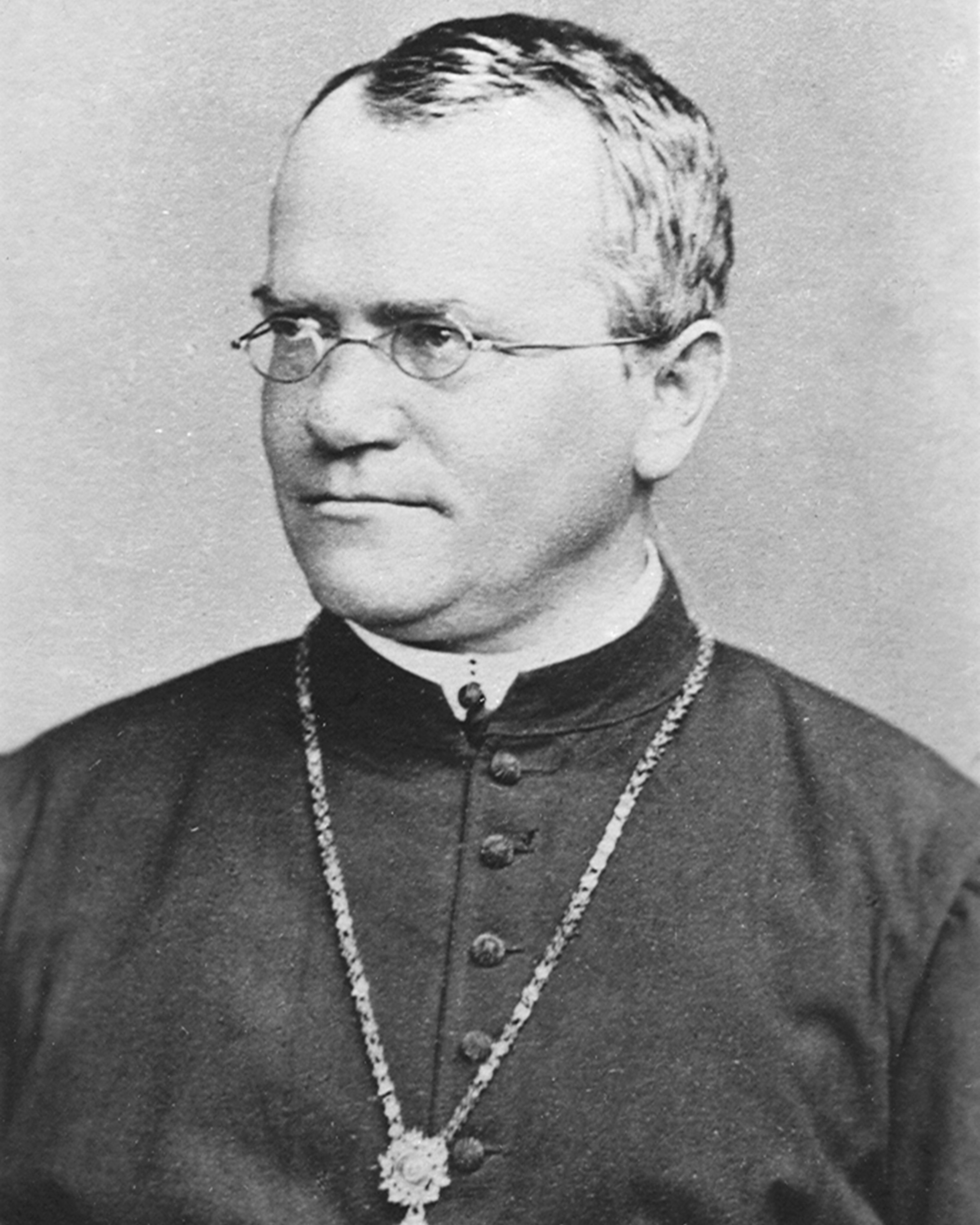

How Gregor Mendel’s pea plant experiments created modern genetics

Mendel’s monastery garden experiments went largely unnoticed during his life, but their implications would ripple through science decades later.

Hidden away in a rural monastery in current-day Brno, Czech Republic, Gregor Johann Mendel planted the seeds of modern genetics.

Known today as the “father of modern genetics,” the Austrian peasant’s chosen career as an Augustinian monk had gotten off to a disappointing start: He had been deemed unfit to work as a parish priest due to “unconquerable timidity,” as his mentor, the abbot Cyrill Napp wrote at the time. However, Mendel’s experience working on his family farm—along with his science and math studies at the University of Vienna—made him an excellent candidate to take care of the monastery garden.

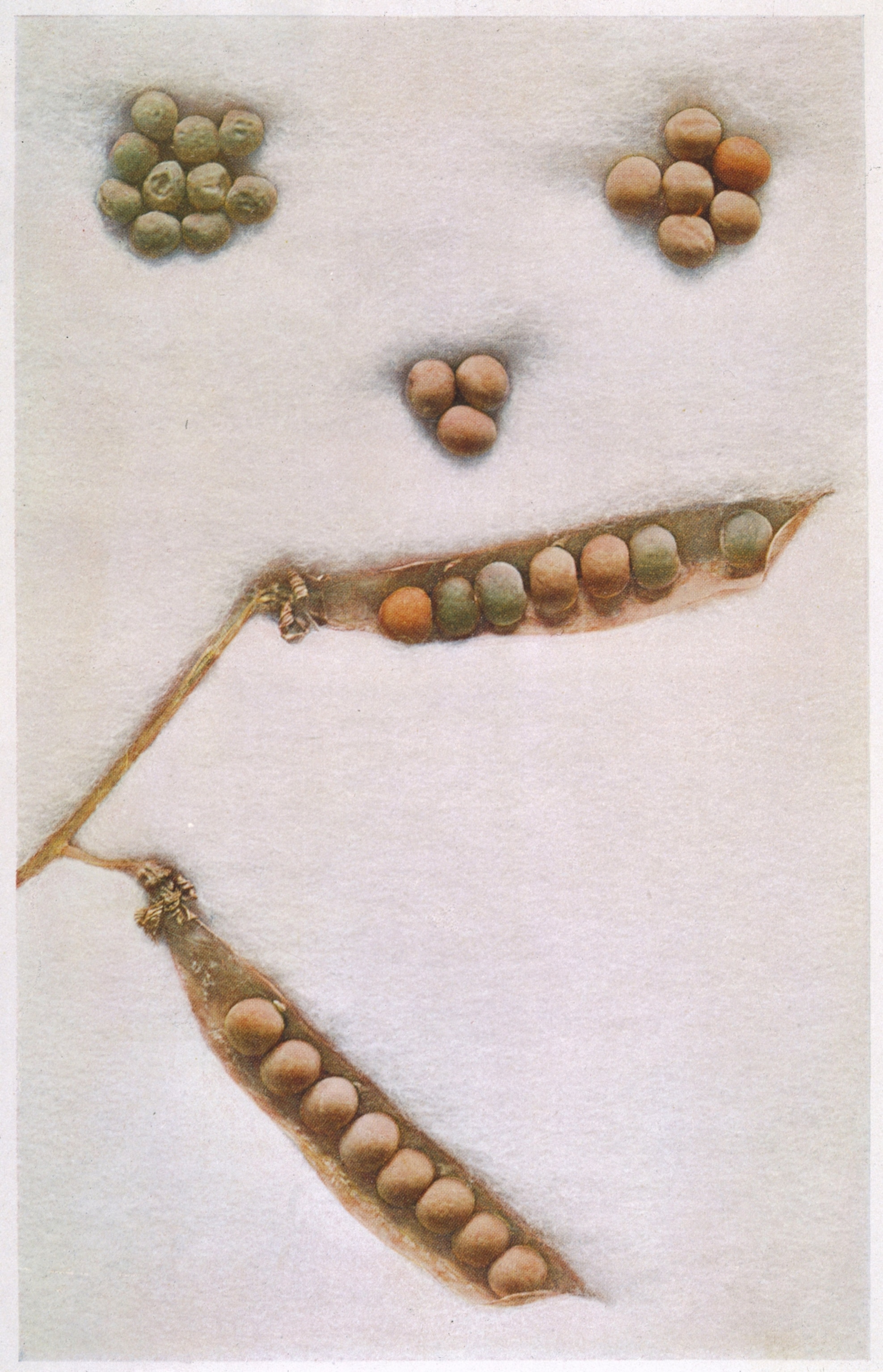

Mendel conducted his now legendary experiments on Pisum sativum, the garden pea, from 1856 to 1863 while living at the Abbey of St. Thomas. Through these studies, he sought to understand how traits like pea color and pod shape passed from one generation to the next. Mendel’s laws of inheritance challenged the dominant theory of blending inheritance—the belief that offspring were merely a blend of their parents' traits.

“Without Mendel's laws, you likely don't get modern genetics,” says Daniel Kevles, Yale University history professor.

Mendel’s work wasn’t recognized until after his death in 1884. “The poor guy had been dead for 16 years or something when people started taking an interest. That's sort of sad,” says Jessica Riskin, Stanford’s Frances and Charles Field professor of history.

Here’s how Mendel’s meticulous work in a monastery garden transformed biology, without recognition during his lifetime.

The pea plant experiments that eventually changed science

Abbot Napp was interested in plant heredity and urged Mendel to conduct experiments in the monastery garden.

So why study pea plants? Well, they were perfect for controlled breeding. Mendel experimented with around 28,000 pea plants for eight years in total obscurity. One pea plant produces dozens of pea pods and hundreds of individual peas, offering Mendel easily observable traits. “You're looking for organisms that are cheap to breed, that breed in abundance, and breed quickly,” Kevles explains. This gives you the best chance of seeing “statistical patterns.”

Mendel’s breakthrough grew out of a rigorously controlled experiment he began in 1856, grounded in careful, sustained observation. No detail was too small as the biologist documented the seven traits of pea plants—the shape of the seeds, the color of the albumins, or pea proteins, the color of the seed coats, the shape of the pods, the color of the unripe pods, the position of the flowers, and the length of the stems. Then, Mendel meticulously recorded what traits the next generation of pea plants possessed when they were self-pollinated versus cross-pollinated.

No one, not even Mendel himself, knew that he was making a major scientific discovery until later. Previous scientific understanding held that new generations are a mix of their two parents. Mendel’s observations refuted that belief. His research accidentally found that “particles”—later known as genes—delivered inherited traits to the next generation.

Mendel wasn’t trying to answer questions about plant heredity when he started his experiments, Kevles says. “The key to what primarily interested Mendel himself is that he was a well-known breeder of floral plants, hybridized to produce different colors.” Mendel was trying to figure out if a specific set of laws could determine the type of offspring hybrid plants produce.

Mendel outlined his findings to roughly 40 attendees in two presentations at the Natural Science Society of Brünn (modern-day Brno) on February 8 and March 8, 1865. His paper, which was published the following year, contained the three principles of inheritance known today as Mendel’s laws. At the time, though, his ideas didn’t garner much notice.

(The Human Genome Project and other scientific breakthroughs of the last 25 years.)

Mendel’s first principle was the Law of Dominance and Uniformity, which explains that some traits, like freckles, are dominant while others are recessive, meaning that offspring have to inherit two copies of the gene for it to appear. The second principle—the Law of Segregation—describes how genes are distributed to offspring, with one copy of a gene for a given trait coming from each parent. Mendel’s third and last principle—the Law of Independent Assortment—states that each trait passes to offspring independently of the others. You may inherit your mom’s blue eyes, but that does not mean you’ll also inherit her red hair.

Why Mendel’s research was ignored for decades

While monumental to the advancement of genetic research, Mendel’s work didn’t gain recognition during his lifetime due to his lack of close ties to the broader scientific community. “He didn’t know anybody. He wasn’t a correspondent of Darwin or anything,” says Riskin.

In addition to his relative obscurity as a scientist, heredity wasn’t a popular area of focus when Mendel made his discoveries. Scientists of the mid-19th century focused largely on evolution, explains Kevles.

In the years following Mendel’s death in 1884, evolutionary biologists began to use agriculture to examine how change occurs in species. Botanists grew large quantities of plants to better understand how traits passed between generations and hopefully improve their quality.

In 1900, three scientists unknown to one another—Carl Correns, Erich von Tschermak, and Hugo de Vries—independently rediscovered Mendel’s work, stumbling on the key to what we now call genetics.

The field of genetics was formed during the 20th-century. “Mendel did not use terms like gene or genetics,” says Sharon Kingsland, history of science and technology professor at Johns Hopkins University. “After 1900, other biologists drew inspiration from his work to argue for the creation of the field that would be known as genetics.”

The word “genetics” wasn’t even used until 21 years after Mendel’s death. Biologist William Bateson first used the word in a 1905 letter to colleague Adam Sedgwick, proposing the term as a name for inheritance studies as its Greek roots mean "to give birth."

The term was adopted a year later at London’s International Conference on Plant Hybridization in 1906. The term “gene” was first coined in 1909 by botanist Wilhelm Johannsen, finally giving a name to the “particles” Mendel had described in his work over 40 years earlier.

Mendel’s legacy in modern genetics

“Others would have discovered Mendel’s laws, given time,” Kevles says. “But Mendel was there first, and he knew what he was doing.”

Mendel’s work remains fundamental to the modern-day field of genetics and understanding how traits pass from generation to generation for many species, including humans. His laws of inheritance also advanced modern evolutionary biology by answering a question Darwin couldn’t––how offspring receive traits from their parents.

Mendel had faith that his genius would be recognized. Just months before his death, he told another monk, “my scientific work has brought me great joy and satisfaction; and I am convinced that it won't take long that the entire world will appreciate the results and meaning of my work.”