80 years later, you can still see the shadow of a Hiroshima bomb victim

In the wake of the blast, these eerie shadows were left etched into surfaces across the city—almost like a photo negative of those who were lost.

It was business as usual in the morning of August 6, 1945, in Hiroshima, Japan. In the city’s financial district, bankers prepared for the day and customers queued up to deposit money or apply for a loan.

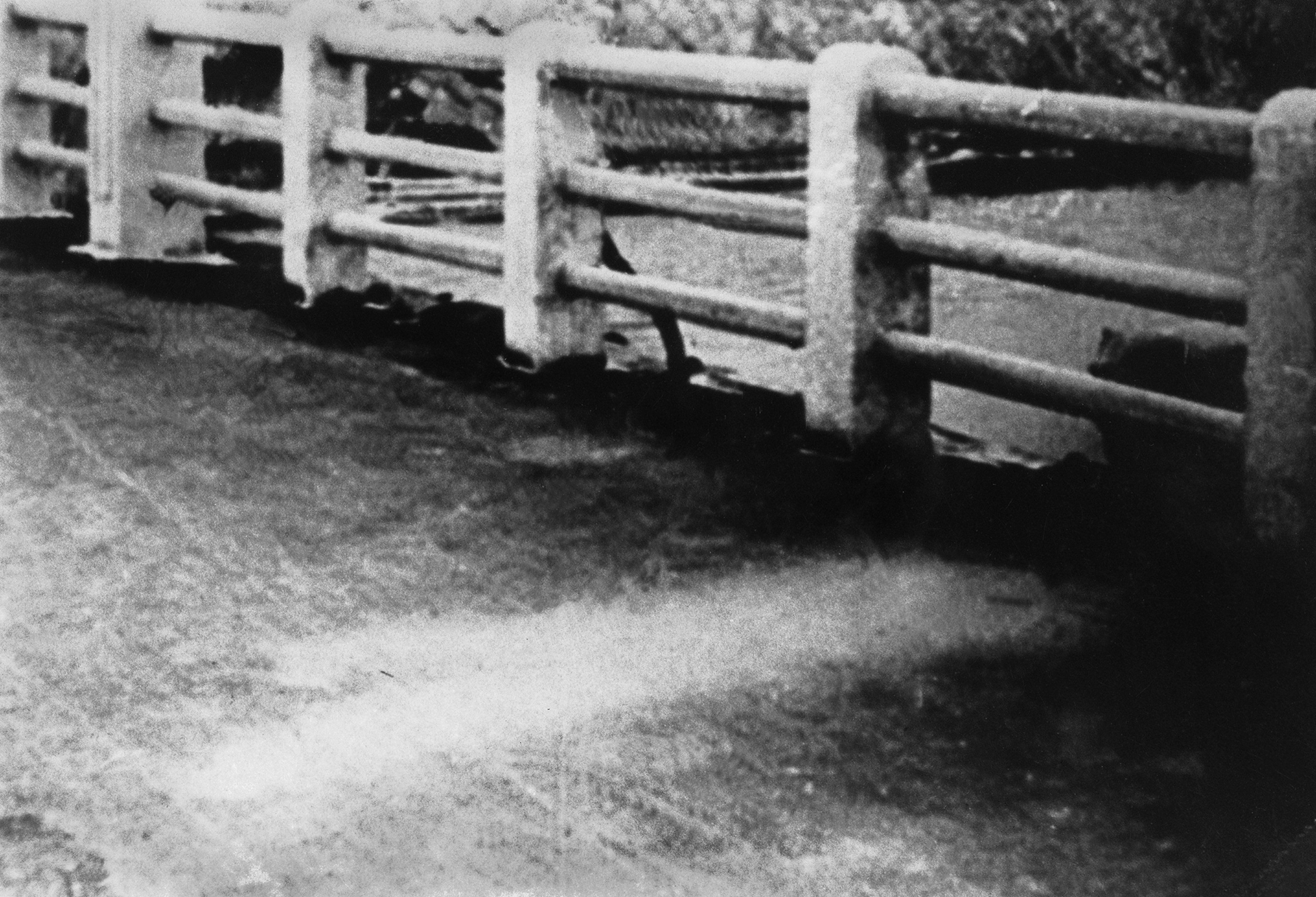

At 8:15 a.m., someone was either standing or sitting on the steps of Sumitomo Bank when the Enola Gay, a U.S. Army Air Force plane, flew overhead and dropped an atomic bomb that detonated 1,900 feet above the city.

That person likely died immediately, as the intense heat at the center of the blast would have been in excess of 7,000 degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to swiftly kill anyone. But a shadowy imprint of their body was left scorched onto the stone steps.

And this mark wasn’t alone: The intensity of the bomb created so-called nuclear shadows throughout the area on the ground beneath the explosion, as if freezing the city in time.

Now, 80 years after the bomb, Hiroshima’s nuclear shadows remain a chilling, poignant testament to one of the most consequential days in human history.

How did the Hiroshima nuclear shadows form?

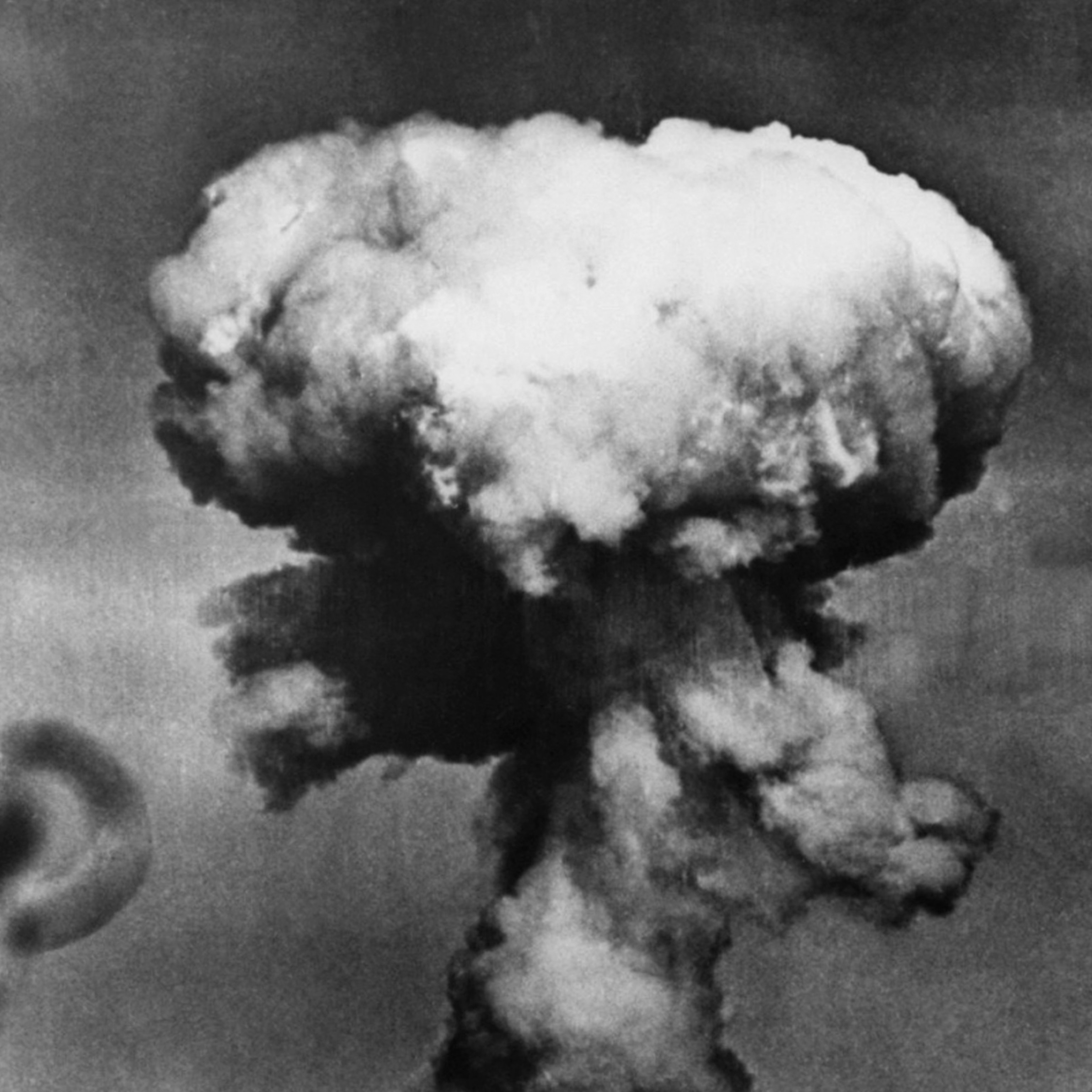

The 10,000-pound atomic bomb that detonated over Hiroshima unleashed a massive amount of energy—the equivalent of around 15,000 tons of TNT—in a fraction of a second. That energy took the form of several things: light, heat, radiation, and pressure.

The explosion’s intense heat washed over Hiroshima at a pace of 186,000 miles per second and was over as quickly as it had begun, according to the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, an official report on the effects of the bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The explosion had flash-burned everything within 9,500 feet, charring trees and casting UV light so powerful that it bleached non-combustible surfaces like stone and concrete.

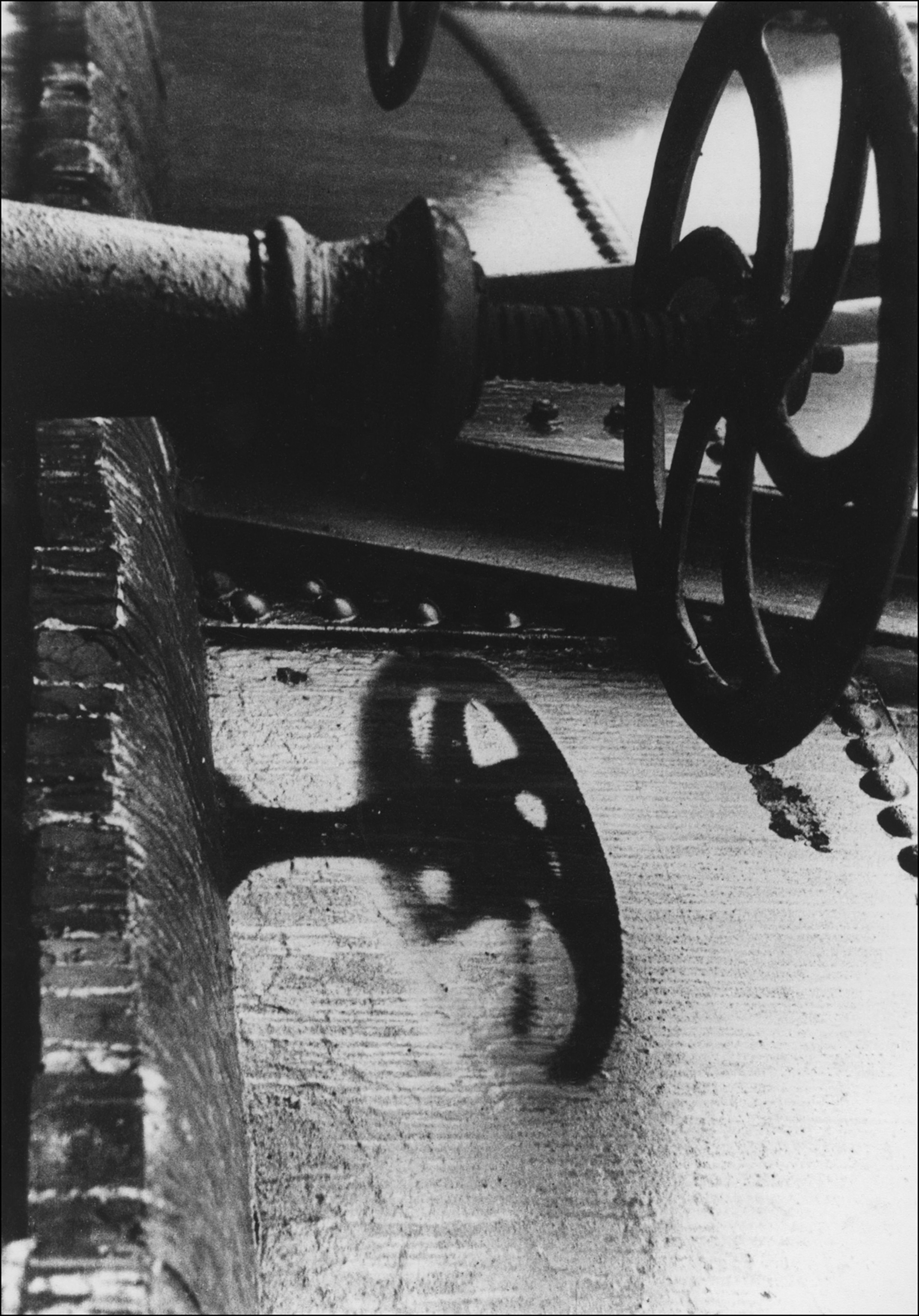

This process is what created the nuclear shadows—they aren’t the remains of people and things that were destroyed in the blast but rather they were etched like a photo negative in places that had been protected from the destructive path of radiant heat and light.

Sumitomo Bank, only 260 meters from the bomb’s hypocenter, was one of about 70,000 buildings in Hiroshima that the bomb damaged or obliterated. “[The bank’s] reinforced concrete outer walls remained, but most of the interior was completely burned out,” says Ariyuki Fukushima, curator at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

And while the bank’s granite steps retained their shape, Fukushima points out that “the intense heat rays from the atomic bomb caused them to become pale and discolored.” The person who had been on the steps during the explosion shielded a section of them from the heat rays, thus creating the shadow.

The same process created shadows of nails, ladders, and other objects on streets and buildings across the city.

What Hiroshima’s nuclear shadows reveal

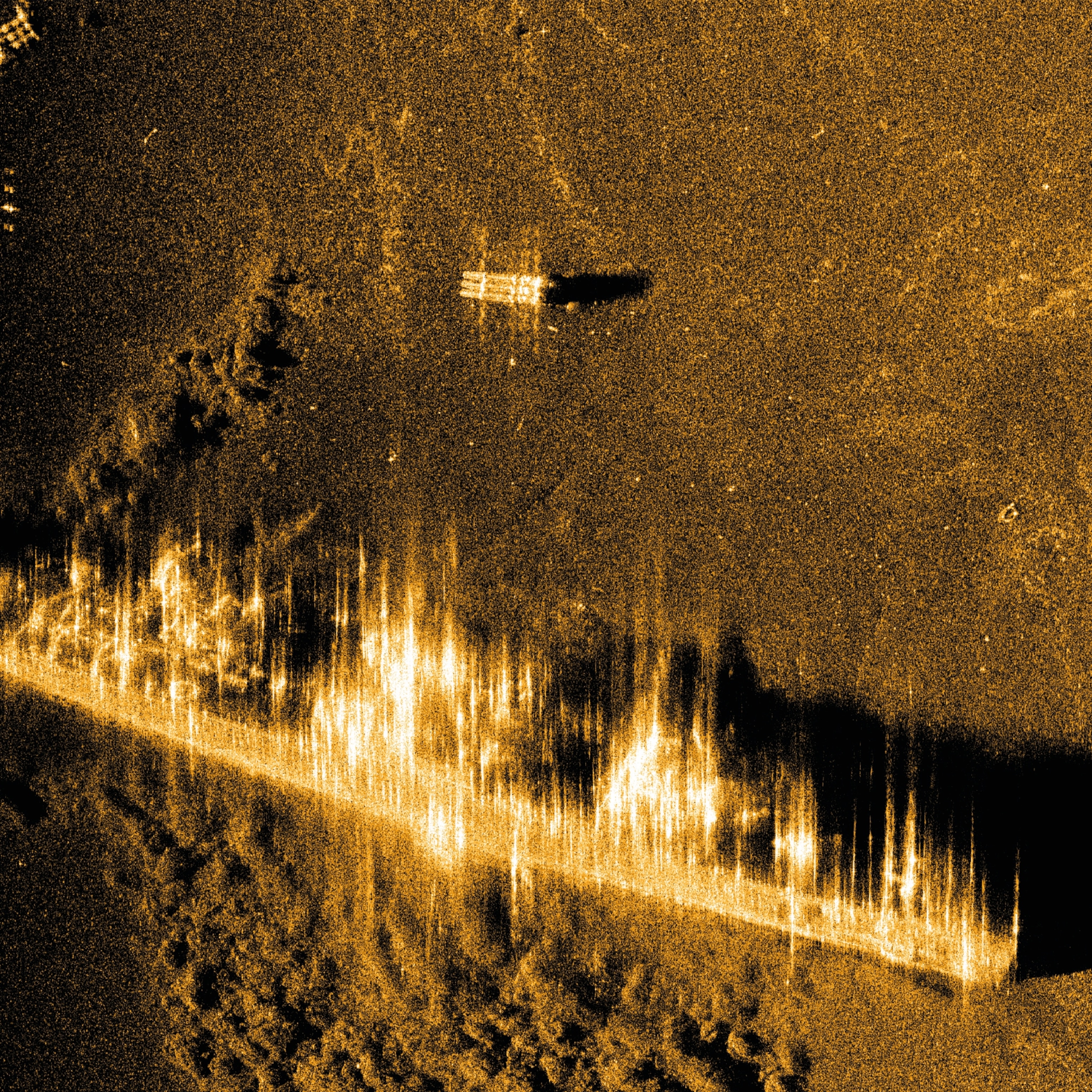

While most of the nuclear shadows depict inanimate objects, a few of them are believed to represent people who were killed. For example, the Yorozuyo Bridge, 910 meters from the hypocenter, appeared to bear shadows of people who may have been on their way to work or school when they were killed. (The shadows are no longer visible on the bridge, which was later rebuilt.)

“Almost everyone who was within a kilometer was killed,” says Robert Jacobs, emeritus professor of history at the Hiroshima Peace Institute and Hiroshima City University.

The explosion killed upwards of 80,000 people in a flash, and thousands more would die in the subsequent days and months.

Among the victims were workers inside Sumitomo Bank. Fukushima notes that only “three individuals are known to have escaped,” though “one of them died a few days later.”

These shadows also helped scientists solve one major question when they descended on Hiroshima in early September 1945, shortly after Japan’s surrender, to study the weapon’s effects. The angle of the shadows “enabled observers to determine the direction toward the center of explosion,” allowing them to locate the bomb’s hypocenter “with considerable accuracy.”

The legacy of Hiroshima’s nuclear shadows

Although we’ll never know the stories of those who were killed in the bomb’s hypocenter, their shadow endures. In 1971, Sumitomo Bank donated its steps to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, where the silhouette remains a haunting symbol of what happened 80 years ago. It is believed to be one of the only remaining nuclear shadows of a person.

Indeed, many of the shadows no longer exist given the decades of rebuilding that the city had to do in the wake of the bombing. Still, Jacobs says the shadows remind us of “the impermanence of humans and civilization.”

“If a person could be reduced to their shadow by a weapon, […] that carries a profoundly existential message to human beings—you and your whole world could be gone in the blink of an eye.”

The shadows are also a solemn reminder of the horrors people faced that day in Hiroshima.

While walking through the ruined city minutes after the bombing, photographer Yoshito Matsushige encountered children who had evacuated their school just before the explosion.

“Having been directly exposed to the heat rays, they were covered with blisters, the size of balls, on their backs, their faces, their shoulders and their arms,” he later recalled. “The blisters were starting to burst open and their skin hung down like rugs.”

These scenes were so horrific that Matsushige couldn’t bear to take any photographs. When he “finally summoned up the courage to take one picture” and then another, he realized “the view finder was clouded over with my tears.”