How political conventions went from provocative to predictable

For nearly a century, presidential candidates didn’t even attend national conventions, where nominations were often contentious and hashed out in backroom deals.

“To Lincoln: You are nominated.”

These five words, with little fanfare, were telegraphed in 1860 from the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, to Springfield, as Abraham Lincoln, former congressman and current lawyer, walked toward his law office there. A crowd surrounded Lincoln in the street, shaking his hand and congratulating him on his nomination as the Republican Party’s candidate for president of the United States. Lincoln later received official notice of his nomination by letter and accepted by one of his own.

For more than a century, nominating conventions were used not to crown a known frontrunner but for party bosses to gather and hash out who should actually run. Presumptive candidates didn’t accept their nominations at conventions, or even attend them. Their acceptance speeches, when they gave them at all, were delivered close to home rather than before their party’s delegates.

But thanks to technology, changes to the U.S. political system, and the dawn of mass media, that changed. Presidential nominations are now a foregone conclusion after a series of primary elections, while the convention itself has shifted into a public event full of laudatory addresses from fellow party leaders and culminating in the candidate’s acceptance speech.

This year, however, marks a return to the past. Due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, neither Democrat Joe Biden nor Republican Donald Trump plan to attend their conventions—which are taking place August 17-20 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and August 24-27 in Charlotte, North Carolina, respectively—in person. Instead, like Lincoln, they’ll receive news of their official nomination remotely.

But why do we have these conventions at all? Here’s how they began and how they evolved.

Early conventions

When the U.S. Constitution was written, it didn’t lay out a process for determining a presidential nominee. For years, political parties relied on a secretiveprocess known by the derisive nickname “King Caucus” to select their candidates. These caucuses were informal affairs in which U.S. Congressmen met to set their parties’ platforms and determine who would run.

Candidates and citizens alike despised this undemocratic system. By the 1820s, criticism had reached a fever pitch and it became clear King Caucus’ days were numbered. But how should parties figure out who to nominate?

An answer came out of left field in 1831, when the nation’s first third party, the Anti-Masons, held the first ever nominating convention in an attempt to do away with caucus secrecy. Though the nominee, William Wirt, only won seven electoral votes in the national election and the party lasted little more than a decade, the idea almost immediately was taken up by the two major political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs, forerunners of the Republicans.

But 19th-century nominating conventions were dramatically different from today’s. In theory, they gave the American people more say in the political process by shifting the nominating responsibility from Congress to state delegates who would vote on the candidates at a national convention. But in reality party insiders controlled these proceedings, too, as they were valuable opportunities to meet and exchange both information and political favors. As presidential historian Gleaves Whitney writes, it was “the era of the proverbial smoke-filled room.” (These are four of the worst political predictions in history.)

Candidates didn’t attend those early conventions, as it was considered immodest to take part in rallying delegates to their side, and nominations were rarely a foregone conclusion. Conventions could be dramatic, boisterous affairs, and issues like slavery split parties into bitter factions. In 1852, for example, the Democratic convention had to hold 49 votes before two-thirds of the delegates could agree on a compromise candidate, pro-slavery Franklin Pierce. Presidential candidates like Pierce instead followed along by telegraph, which Samuel Morse had invented in the 1840s, and responded to the nomination with hometown speeches and acceptance letters.

In the 1890s, a Progressive-era push to further democratize the electoral process led several states to institute a system of primary elections that allowed ordinary Americans to either choose a candidate or the candidate’s delegates directly without party boss interference. Though it now became easier to predict frontrunners, party bosses retained considerable power at the conventions—and presidential candidates still stayed home.

Evolution to modern conventions

Things began to change with the dawn of radio and with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a New York Democrat who had spent over a decade honing his reputation as a skilled speaker stumping for other candidates at political conventions.

During his first presidential campaign in 1932, Roosevelt broke with tradition, flying to Chicago to address delegates in person. Noting that his appearance was “unprecedented and unusual,” Roosevelt told the audience, “I have started out on the tasks that lie ahead by breaking the absurd traditions that the candidate should remain in professed ignorance of what has happened for weeks until he is formally notified.”

Roosevelt’s acceptance speech, which was broadcast by radio to a massive prime-time audience, signaled a new era in candidate participation in political conventions.

Roosevelt missed the nominating conventions for his third and fourth terms in 1940 and 1944—by choice in 1940 and after that due to World War II strategy sessions—and delivered radio addresses remotely instead. (In 1940, his acceptance speech was also broadcast on television, the first time a political convention utilized the medium.) But the precedent had been set: Since 1948, every presidential nominee of a major political party has attended the convention and accepted the nomination in person.

Though more states switched to primary elections over the years, party bosses still occasionally managed to work around the will of voters. In 1968, the Democratic National Convention descended into chaos after Hubert Humphrey, a candidate who had not participated in a single primary race—concentrating instead on non-primary states—clinched the nomination due to backroom dealing by political bosses. (Here's the difference between a caucus and a primary election.)

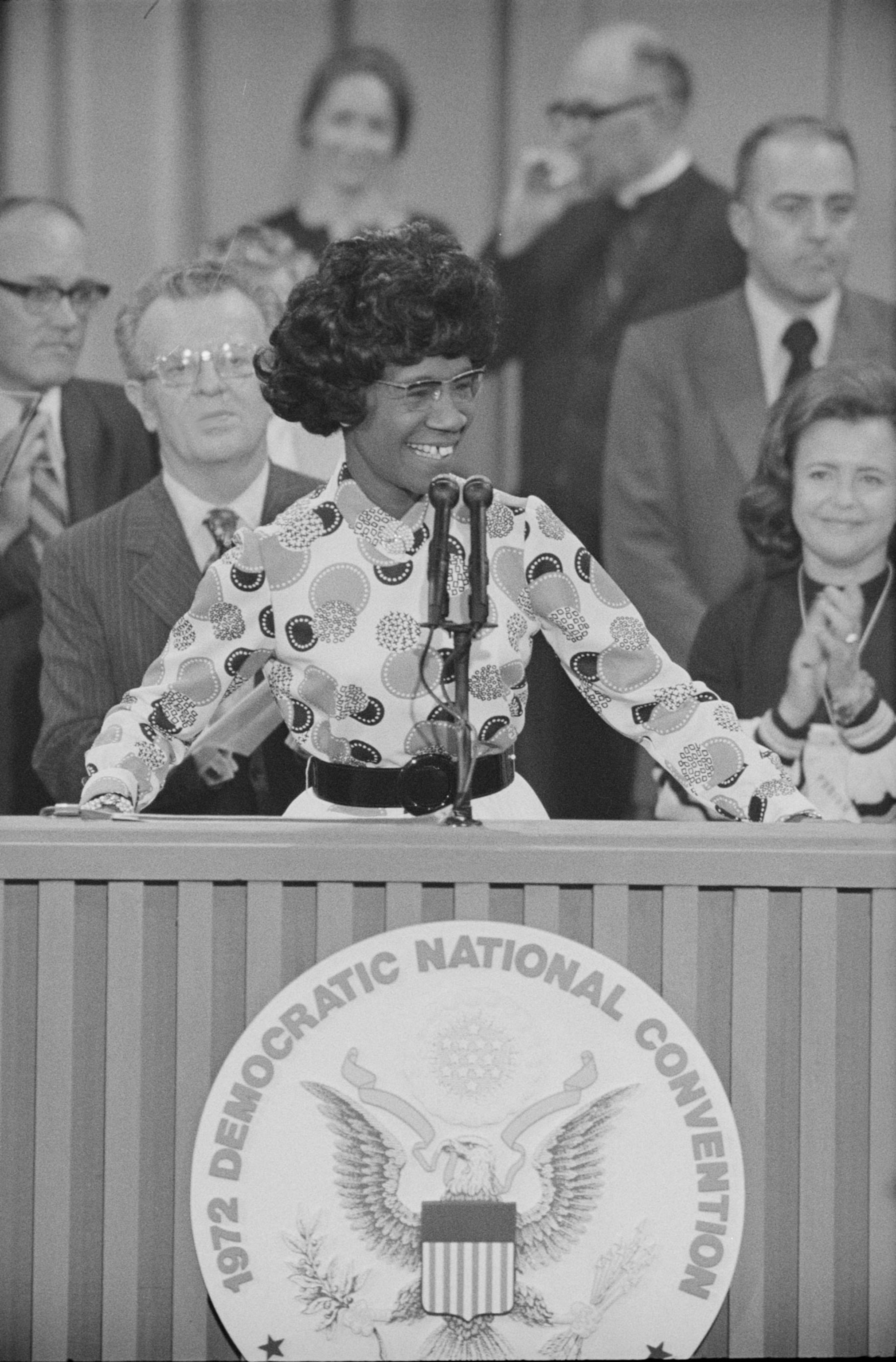

In the wake of the contentious convention, the McGovern-Fraser Commission proposed new rules that permanently wrested control away from political bosses and prompted the majority of states to adopt the primary system.

Since then, contested conventions have become much rarer. Political conventions no longer take place in smoke-filled rooms, but in glitzy auditoriums, and they spotlight party platforms as well as presumptive nominees. That is, until the 2020 pandemic.

This year, both presumptive presidential nominees plan to accept the nomination not at the convention, but closer to home. President Donald Trump has suggested he will give his acceptance speech either at Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania or at the White House itself; presumptive Democratic nominee Joseph Biden has indicated he will give an address from his Delaware home. Perhaps the tradition of hometown nominations has survived, after all.