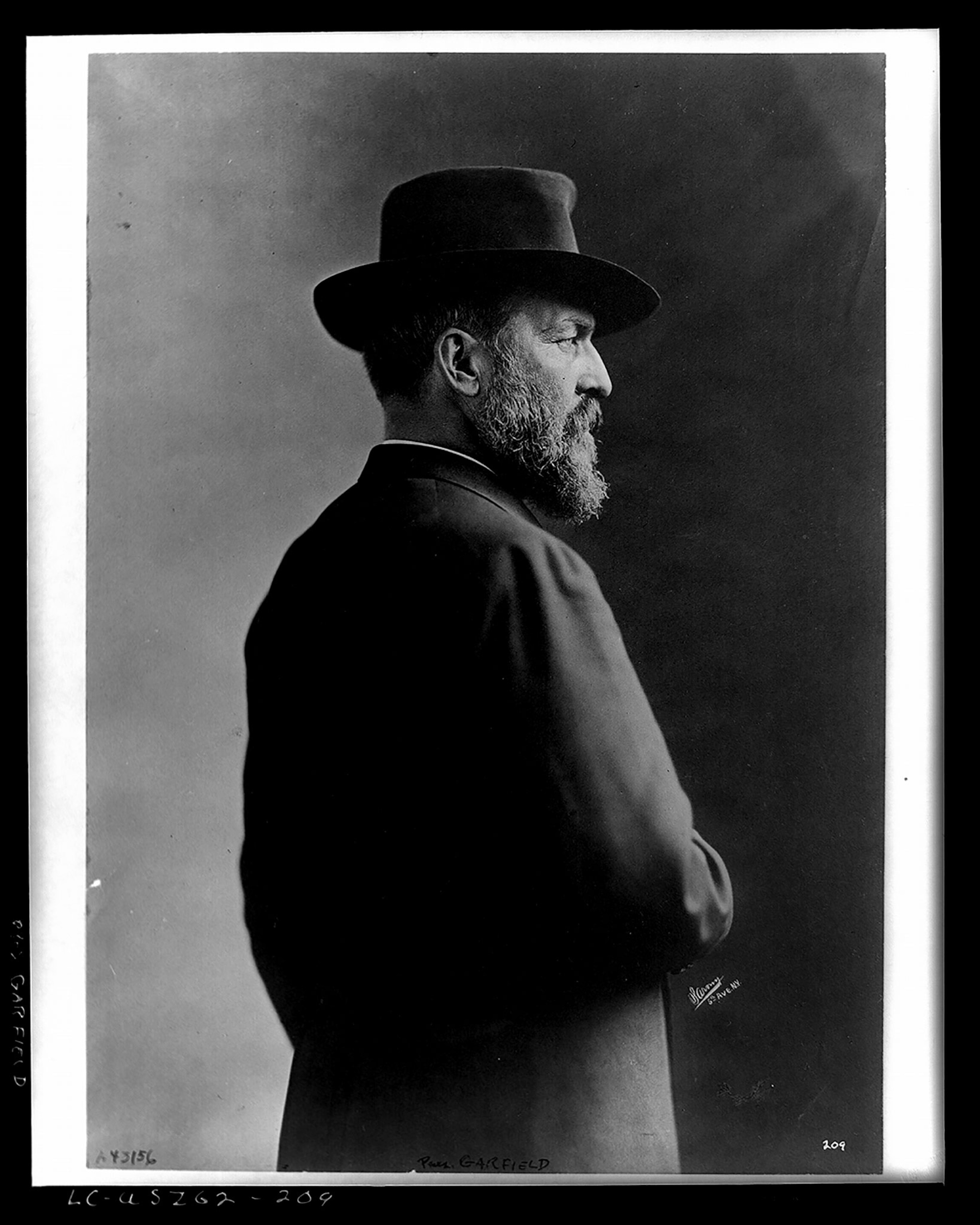

How did James Garfield die? The medical mistakes that killed the forgotten U.S. president

In the summer of 1881, a gunshot at a Washington D.C. train station set off one of the most dramatic chapters in American history—the slow and gruesome death of the 20th president of the United States.

On July 2, 1881, United States president James A. Garfield waited at Washington, D.C.’s Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station to board a train that would take him to New England to begin his summer vacation and reunite with his wife.

The president’s journey home took a deadly turn. Charles Guiteau, a disgruntled would-be federal worker, came up behind Garfield, pulled out a gun, and shot the president twice.

The bullets didn’t initially kill Garfield. Instead, he experienced a slow, agonizing decline characterized by putrid infection, severe pain, and digestive issues. He died on September 19, two months after the assassination attempt.

Why couldn’t the U.S. president be saved in those two months of extended life? The bullets weren’t the only thing that harmed him—his medical team also wreaked havoc on his body.

Garfield’s road to the White House

James Garfield craved a life bigger than the log cabin in which he had been born in Ohio on November 19, 1831. After working on canals and studying at local schools—where he met his future wife Lucretia Rudolph—he gained admission to Williams College.

Garfield left Williams’ campus with a bachelor’s degree and a deep interest in politics. Having served as a major general in the Civil War and as a member of the Ohio State Senate, Garfield became a U.S. congressman in 1863, a position he would hold for the next 17 years.

During the Republican National Convention in 1880, Garfield gave a speech promoting fellow Ohioan John Sherman for the presidential nomination. But it wasn’t Sherman who became the nominee—Garfield, who did not seek the nomination, nonetheless won it in the convention’s 36th ballot.

(How political conventions went from provocative to predictable.)

In November of that year, Garfield defeated Democratic nominee Winfield Scott Hancock to become the 20th president of the United States.

The presidency filled Garfield with apprehension. He wrote on December 31, 1880, just a few months before his inauguration, “I close the year with a sad conviction that I am bidding good-by [sic] to the freedom of private life, and to a long series of happy years, which I fear terminate with 1880.”

How entitlement fueled Garfield’s assassination

Garfield was responsible for making federal appointments, and he was besieged by eager job-seekers.

Charles Guiteau was one of them. Delusion and eccentric, Guiteau had been a supporter of Garfield’s, even making a few speeches on the president’s behalf during the election, and he felt this entitled him to a posting in Europe, despite having no diplomatic experience or meaningful political connections. He hounded the president’s office and made a nuisance of himself until he was banned from the White House.

Claiming God had commanded him to act, Guiteau resolved to assassinate Garfield in retribution so that Chester Arthur—Garfield’s vice president—would take the helm of government.

One thing made Guiteau’s task even easier: Garfield didn’t have bodyguards or any security detail to speak of. The president was virtually a sitting duck.

After stalking Garfield for nearly a month, Guiteau saw a chance. A newspaper published the president’s itinerary for his upcoming trip, including details about when he would leave Washington. Guiteau would be waiting for him.

When Guiteau shot the president on July 2, one bullet grazed Garfield’s shoulder, while the other lodged in his back. Guiteau fled the scene—leaving the president slumped in a pool of his own blood—but police quickly apprehended him.

The shooting hadn’t ended Garfield’s life—not yet anyway. Officials moved him to the White House in an attempt to keep the newly elected president alive.

The treatments that infected Garfield

A medical team, led by Doctor Willard Bliss, quickly formed around Garfield. Bliss had served in the Civil War as a surgeon and provided the president with “medical treatment not dissimilar from that given to wounded Civil War soldiers two decades earlier,” explains Jake Wynn, former director of interpretation at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office. Surgeons typically treated gunshot wounds by extracting the bullet, suturing the wound, and dressing it with lint and bandages. These wounds were susceptible to infection, however, since bullets could bring bits of clothing and dirt into the wound.

The medical team operated under another holdover from the Civil War era: an inability to prevent infection. The knowledge did exist at the time of Garfield’s assassination. In 1865, the same year the war had ended, British surgeon Joseph Lister had developed a method to keep wounds and instruments clean with carbolic acid. However, “Garfield’s medical team were not followers of Lister’s surgical techniques,” Wynn explains. They probed his wound for the bullet with fingers and instruments that hadn’t been sanitized.

“This was bad practice even by 1880s standards,” says historian Kenneth D. Ackerman, author of Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield. “Doctors on the western frontier who treated gunshot wounds on a regular basis even sent letters warning Lucretia to not let the doctors examine the wound, just let it heal.”

The result? Infections and blood poisoning ravaged Garfield.

Physicians doggedly attempted to locate the bullet. They even asked inventor Alexander Graham Bell to use a metal detector to help them find it, but the sick bed’s metal bedsprings made it difficult.

The medical team was probing in the wrong place. Physicians had misjudged the bullet’s trajectory, believing it was lodged on his right side when Garfield’s autopsy later revealed it had veered left. As a result, they “created a separate channel through Garfield’s body that let infection spread internally,” Wynn explains.

After several weeks, his medical team made another disastrous decision. To help drain an abscess, physicians created another incision—but it was neither sterile nor big enough, only another avenue for infection.

Garfield languished for 79 days

Garfield’s convalescence was excruciating and undignified. He fell in and out of fever and often struggled to withstand the pain or keep food down. To help with the pain, his physicians administered opium; to nourish him, they fed him rectally.

Garfield’s weakened body festered in the Washington D.C. heat, though his doctors attempted to devise what historian John Clark Ridpath called “a simple refrigerating apparatus” that lowered the temperature in the room to a more comfortable 77°F.

He was eventually moved once more, this time to a seaside house in Elberon, New Jersey, where it was believed the cool, clean sea breeze would be good for him.

It didn’t cure him, but it gave him peace in the final days of his life. He died on September 19, 1881, just 199 days into his term, making his presidency the second shortest in U.S. history.

Was Garfield’s death preventable?

The public mourned Garfield and became incensed at his physicians’ inability to save him. “The prevention of septiceaemia […] was everything; the treatment after its occurrence almost a hopeless task,” one anonymous physician wrote in the New-York Tribune on September 23.

Lack of faith in the president’s medical team had become so widespread that Guiteau quipped on the first day of his trial in November, “The doctors ought to be indicted for murdering James A. Garfield, not me.”

Sanitation and sterilization were at the heart of some of the outrage, especially since “proponents of Lister’s anti-septic techniques [had] raised fears about Garfield’s medical care in the weeks leading up to the president’s death,” Wynn says.

“In the years that followed, Lister’s techniques and subsequent advancements took root in the U.S,” as more physicians and the general public became receptive to sanitation and sterilization practices.

Had Garfield’s physicians applied Lister’s antiseptic methods, his story might have ended differently.

“Certainly, modern medicine would have saved Garfield’s life,” Ackerman argues. “Even 1880s medicine probably could have saved his life. Had the doctors simply cleaned the wound and nursed Garfield back to health, he likely would have lived.”