Newly Released Maps Show How Housing Discrimination Happened

A new online collection of documents shows historical bigotry in banking and real estate.

The maps in this post are part of a grim history. They were created by a government program in the 1930s and played a role in keeping African Americans and other minorities from owning property in American cities, thereby leaving an indelible mark on the racial and economic history of the United States.

Now, for the first time, hundreds of these maps and documents are available online in one place.

The collection, called Mapping Inequality, includes maps and notes from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a federal program established during the Great Depression to shore up the housing market.

The HOLC was tasked with figuring out the investment risks in various cities so banks could determine where to give out loans. To do this, the organization often relied on local real estate agents and lenders, who, in many cases, judged neighborhoods based largely on their racial and socioeconomic makeup. Less affluent neighborhoods and those with significant minority and foreign-born populations got lower ratings and were colored red on the maps, a practice that came to be known as "redlining."

Low ratings from HOLC made it difficult for many minorities and poor whites to take out a loan to buy a house—a legacy of discrimination that’s still being felt today. (Though there’s still some debate among historians over whether HOLC and the maps it produced actually caused housing discrimination, or merely reflected discriminatory practices that were already happening).

The redlined neighborhoods didn’t necessarily have high mortgage default rates to begin with, says Nathan Connolly, an urban historian at Johns Hopkins University and one of the leaders of the effort to digitize the HOLC documents and put them online. But the act of redlining areas meant that homeowners who got in trouble during the Depression wouldn’t be eligible for a bailout. “It became a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

“These residential decisions had decades-long consequences,” Connolly adds. “So much of the wealth inequality that exists in America is driven by inequality in real estate market and the ability to generate equity and pass it down from one generation to the next.”

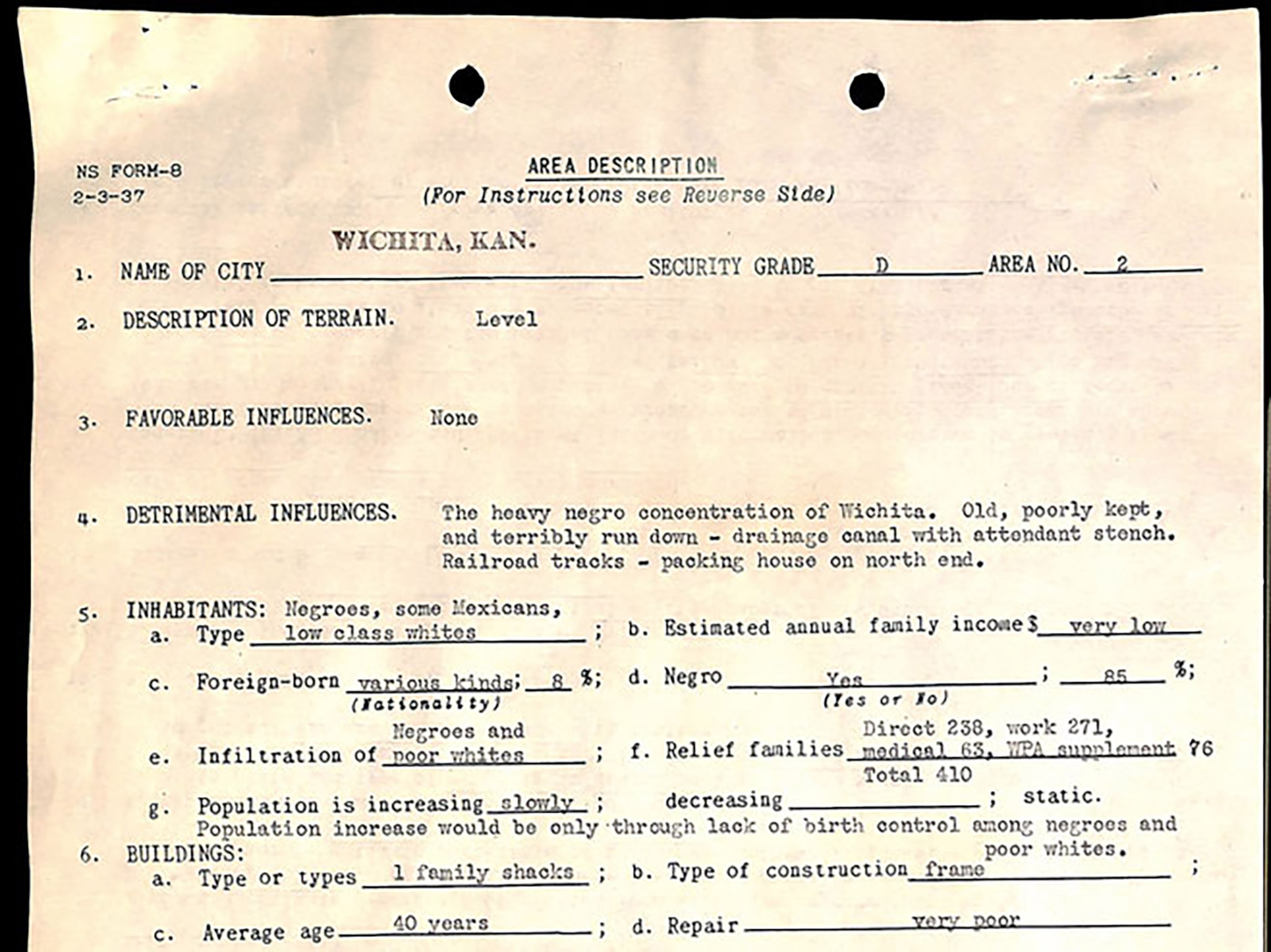

Some of the documents make plain the racial discrimination at play. In Miami, local assessors working for HOLC described the detrimental influences on one neighborhood as: “Close to dump and Negro area.” In an area near downtown Portland, Oregon, the downsides included “Infiltration of subversive racial elements.”

The 1937 map below depicts a large redlined area in the center of Wichita, Kansas. The notes that accompanied the map (there’s an excerpt at the bottom of this post) reveal some of the reasons. Area D-2, near the center of the map, contains “the heavy Negro population of Wichita,” according to the notes. The assessors described the area’s desirability as “as low as it can be” and predicted that the only reason the population there would increase would be “through lack of birth control among negroes and poor whites.”

The local real estate agents who did the assessments reinforced the racial biases of their time, Connolly says. “The assumption was that any discernable black presence would be undesirable to ‘mainstream buyers,’ which is another way of saying white buyers.” The real estate agents also had significant conflicts of interest: The ratings they issued had a big influence on the value of the properties they were buying and selling.

As a result of redlining, many African Americans had to rent housing, often at exorbitant rates, from landlords who knew they had no choice. And people in white neighborhoods often tried to protect their property values by adding so-called restrictive covenants to real estate contracts. “These are agreements that say, ‘OK, we’ll sell you this house on the condition that you’re never going to build a barn on the property, you’re never going to build a liquor store, and you’re never going to sell it to black people,’” Connolly says.

The HOLC maps and notes have always been open to the public at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and some have been put online previously, but this is the first time so many of them have been available to anyone with a computer. Richard Marciano at the University of Maryland, Rob Nelson of the University of Richmond, and LaDale Winling of Virginia Tech spearheaded the project along with Connolly.

On the Mapping Inequality website you can easily find maps of many major cities and click on the neighborhoods defined by HOLC to pull up the corresponding notes (though not all of them have been uploaded yet). There’s also a slider that changes the transparency of the HOLC maps so you can see the modern street grid underneath. Connolly and his colleagues hope the collection will be a valuable resource for historians—professionals and amateurs alike—as well as for ordinary people curious about the history of where they live, or where they came from.