14 Photos That Illumine a Dark Chapter of U.S. History

Seventy-five years after his forebears were sent to internment camps, a photographer is recovering pieces of his lost past.

Seventy-five years ago, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The directive set the stage for the largest forced relocation in American history.

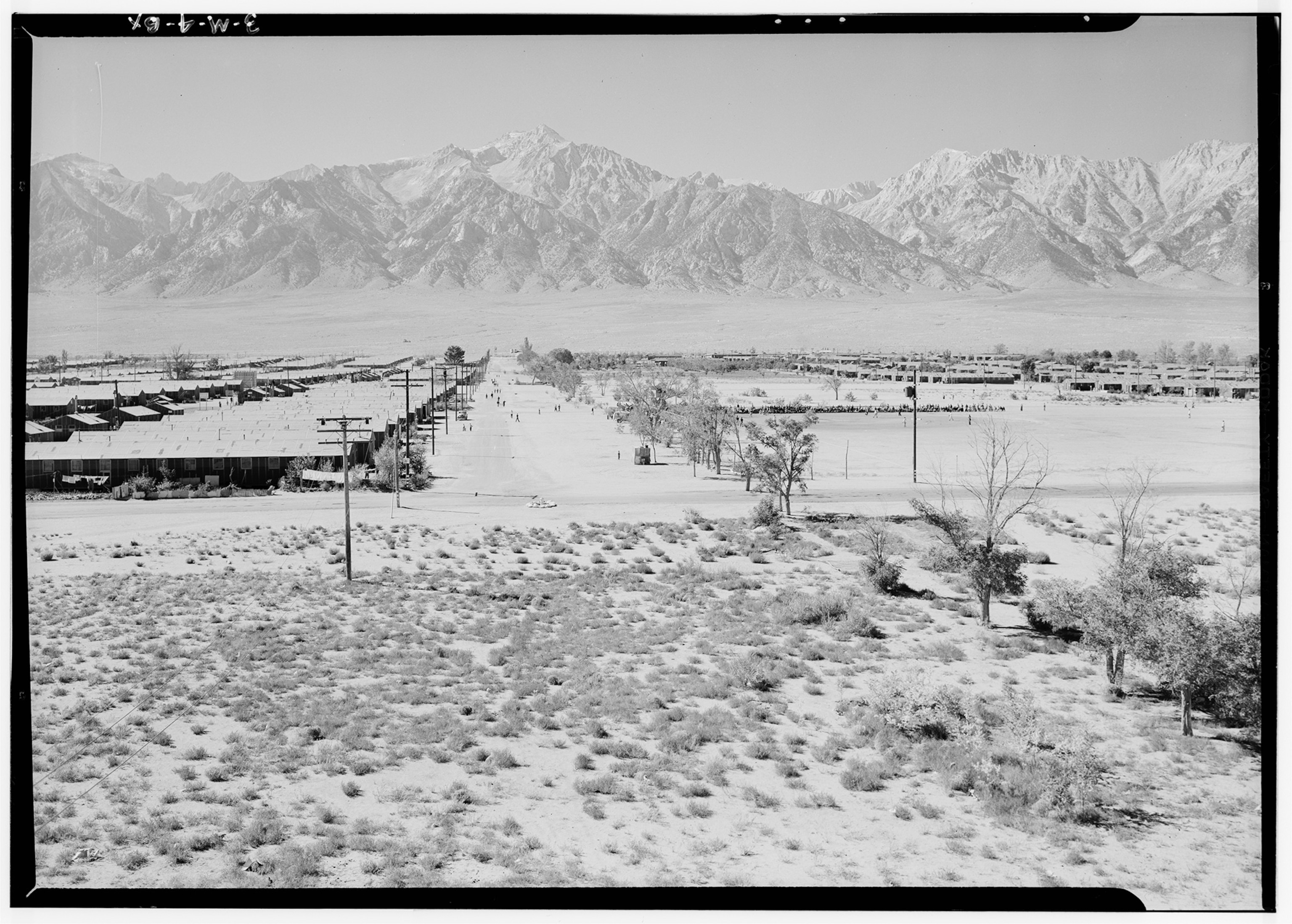

The sting of the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor was still fresh, and there were rumors of an imminent invasion of the U.S. Pacific Coast. In response, the federal government took draconian action, ordering more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry—aliens and citizens alike—to evacuate the West Coast and move inland to 10 "relocation centers" scattered across remote parts of the country, far from populated areas and the war industry.

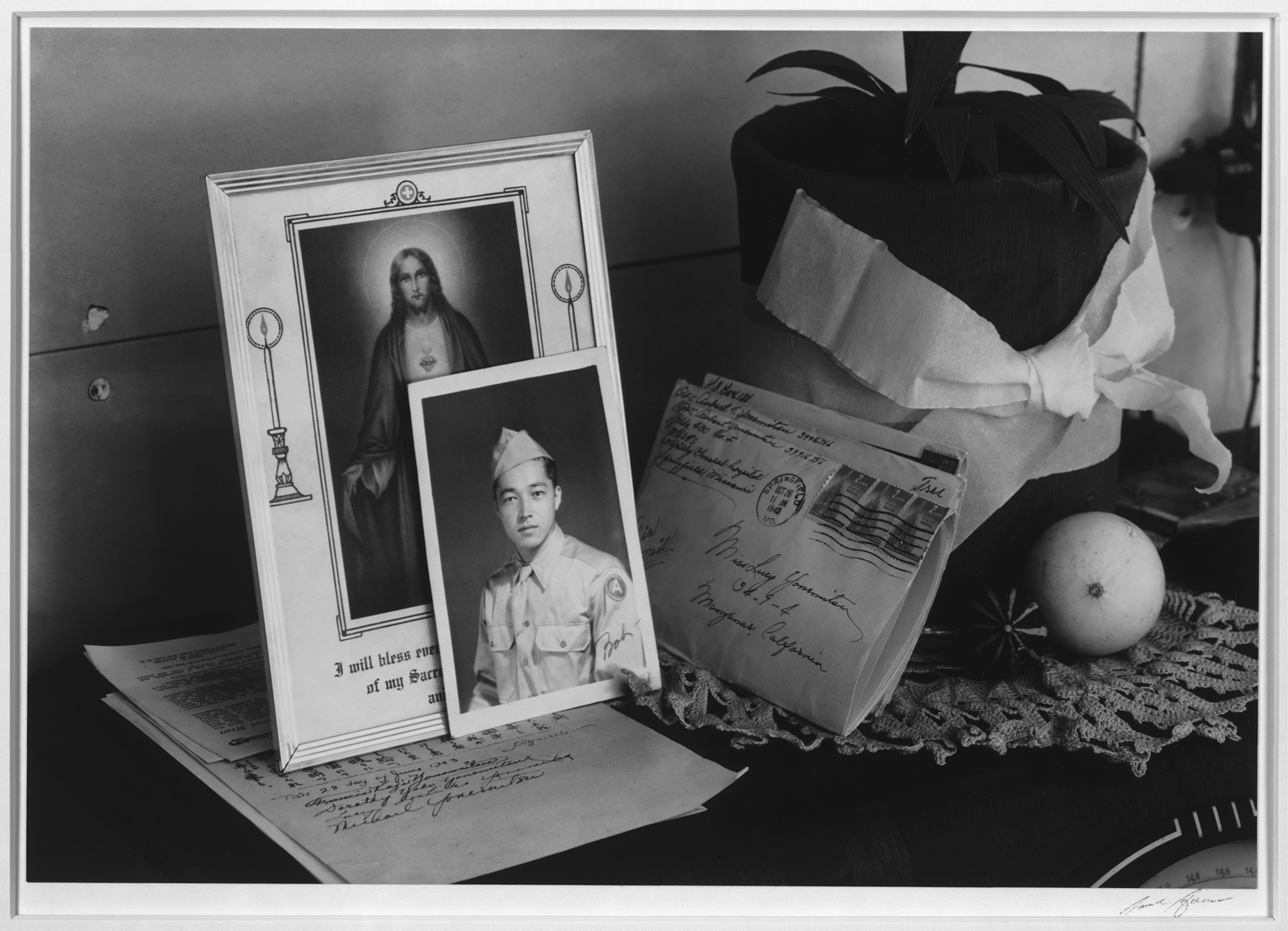

To deter any would-be saboteurs, the military confiscated all weapons, radios—and cameras. This led to "a gap in the Japanese American family album," says photographer Kevin Miyazaki, whose father was 13 years old when he and his family were sent to an internment camp. "I think we have only four photographs of our family from that period."

The ban on cameras wasn't the only reason for the dearth of family photos, says Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, a professor of Asian American studies at the University of California, Los Angeles.

"Because of the FBI sweeps right after Pearl Harbor, a lot of families destroyed photo albums and other memorabilia that linked them to Japan," he says. Such items might have been interpreted as evidence of disloyalty to the United States.

In 2007 Miyazaki visited Tule Lake in Northern California, one of two internment camps where his father's family was incarcerated. There Miyazaki learned that at the end of World War II the camp barracks were turned over to a government-sponsored homesteading program and distributed to returning veterans, who repurposed them for homes, barns, and outbuildings. Some of the recycled structures are still in use today.

Since that discovery, Miyazaki has been photographing the former barracks in hopes of recovering some pieces of his lost past.

"Searching for the buildings and approaching their owners is an important part of the process," Miyazaki says. "I'm seeking family history—both my own and that of the current owners—and we often spend time sharing our uniquely American stories."

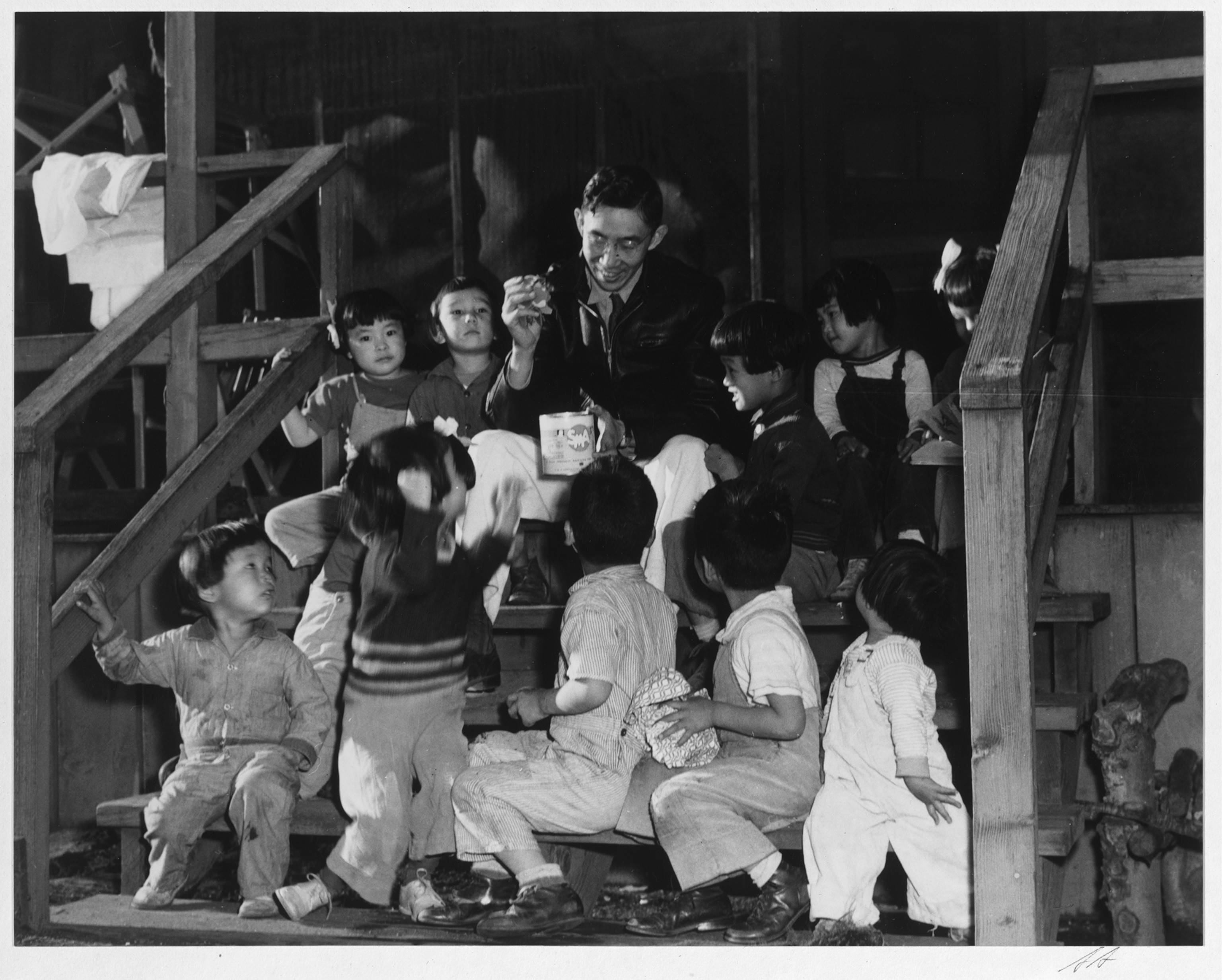

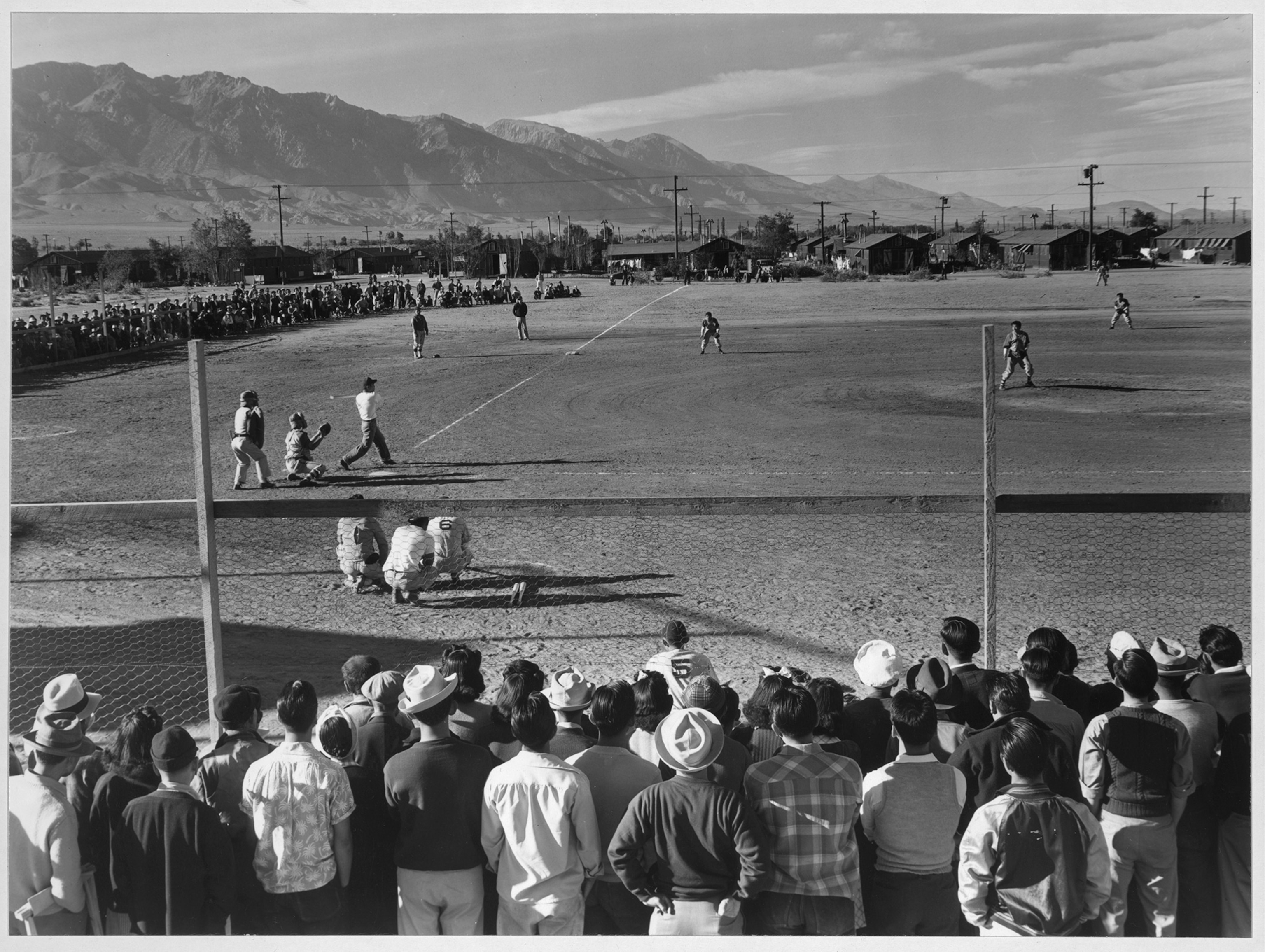

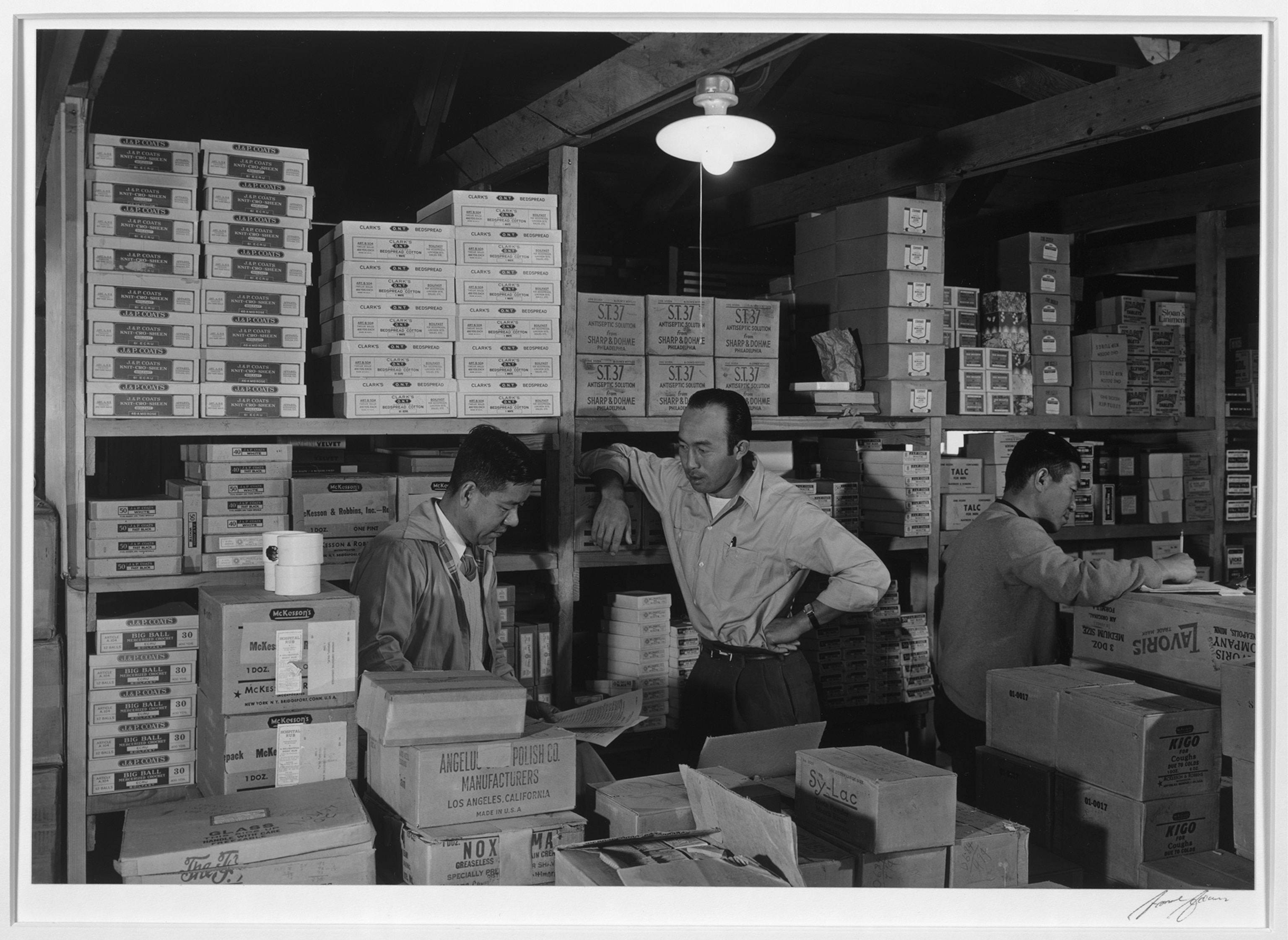

Another photographer whose images help illumine that dark chapter of American history is Ansel Adams. In 1943 the famous landscape photographer was invited to document the daily life of internees at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in eastern California.

"The purpose of my work," Adams later wrote, "was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and despair by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment."

For some U.S. residents today, the photographs by Miyazaki and Adams may take on new urgency in light of recent calls for a registry of American Muslims.

"When I hear talk about a Muslim registry, I think about two homemade wooden crates in the basement of my mother’s house," Miyazaki says. Both are marked with "the number assigned to my father’s family before they were sent to incarceration camps."