London’s most notorious thief was also a hero of the people

An expert in picking locks, Jack Sheppard rose to fame in the 18th century for his spectacular escapes from London’s notorious prisons—but harsh English laws against theft eventually sent him to the gallows.

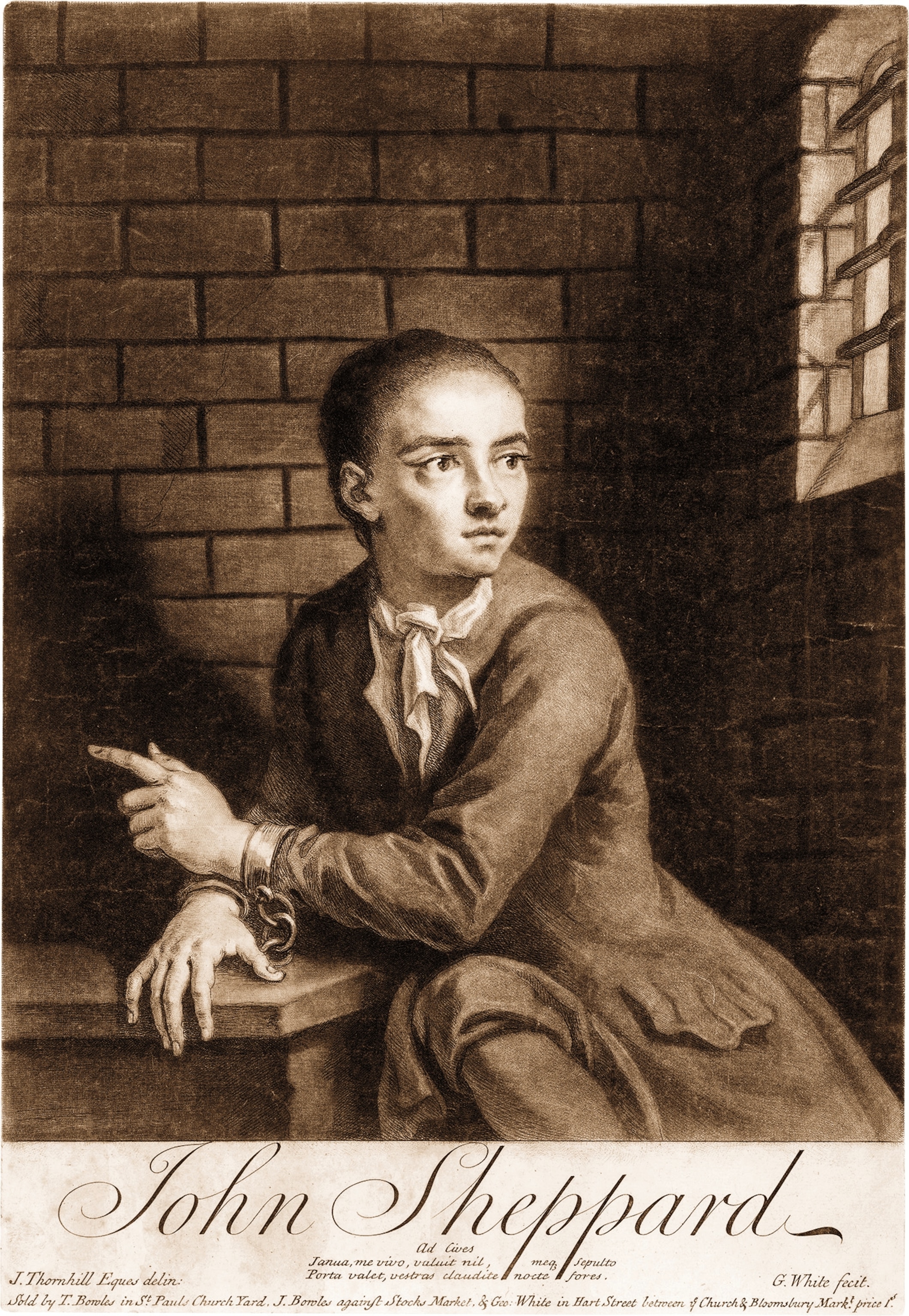

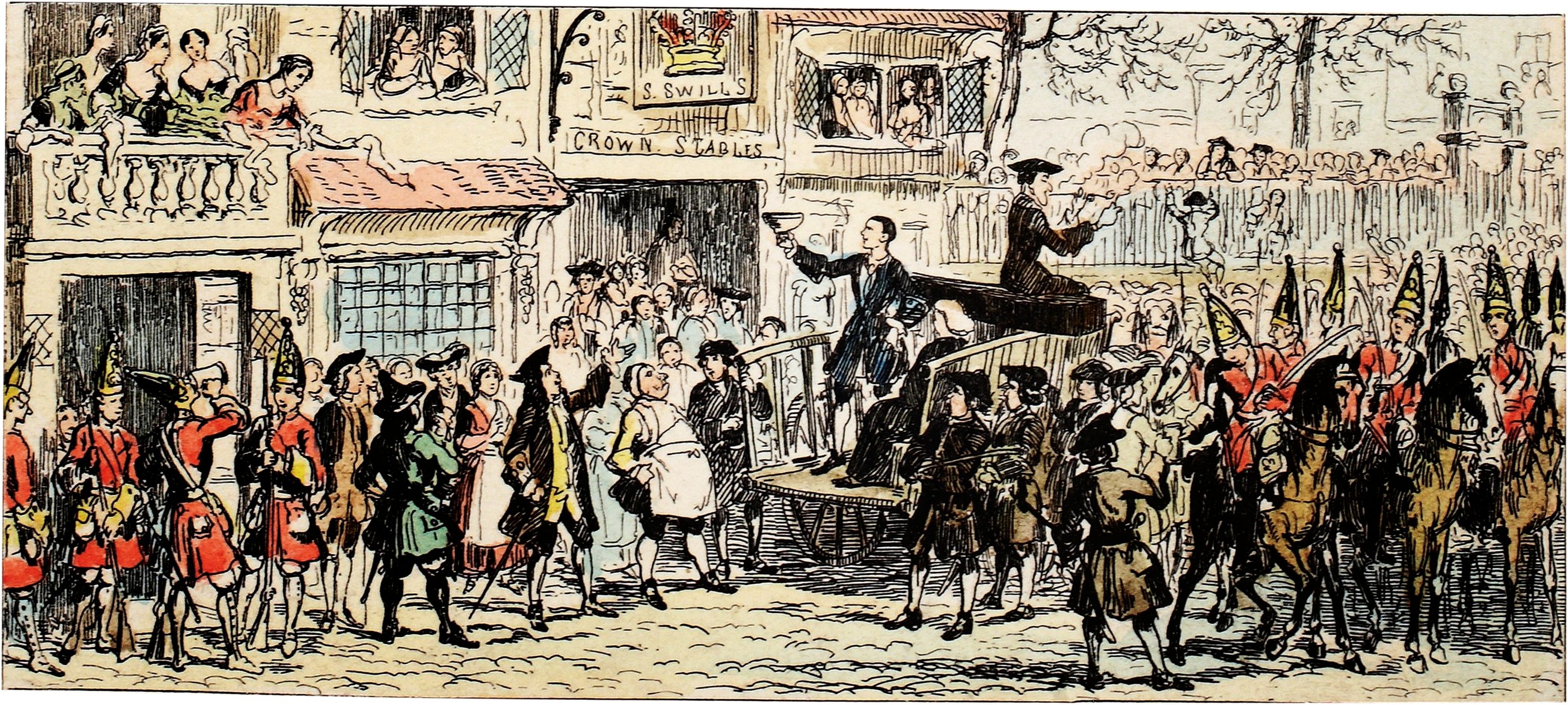

On November 16, 1724, a 200,000-strong crowd gathered around the gallows at Tyburn, London, to witness the execution of 21-year-old John “Jack” Sheppard. Formerly a carpenter’s apprentice, Sheppard had become, according to historian Peter Linebaugh, a household name in 18th-century England. Sheppard owed his fame to his extraordinary, daring prison breaks—at a time when the British working class was suffering under an increasingly draconian criminal justice system.

Sheppard was born in 1702 in Spitalfields, now East London, into a humble family of carpenters. His father died when he was just four, leaving his mother to raise three children on her own. As soon as Sheppard came of age, he followed in his father’s footsteps and started work as a carpenter’s apprentice. Physically small but very robust, he soon became skillful at handling locks and bolts. With a taste for fine clothes and luxuries well beyond his means, Sheppard became a regular in the city’s taverns and was often seen in the company of prostitutes. He moved in with one such woman named Elizabeth Lyon, better known as Edgeworth Bess, after her hometown. The legend of Jack Sheppard, popularized by the English writer Daniel Defoe, says that Lyon led him astray and drew him into a life of crime. The idea of a woman being the root of a man’s downfall was a common trope in 18th-century literature. Sheppard had, in fact, already been involved in petty theft before meeting Lyon.

Whatever led Sheppard down that path, he was far from being alone. Britain’s unregulated commercial and colonial expansion was pushing many working-class people to the margins of society. Thieving and banditry were thriving. Figures like the highwayman Dick Turpin gained notoriety for galloping across the countryside to rob carriages on remote roads. Meanwhile, in London, gangster Jonathan Wild amassed an enormous fortune through organized crime—while operating as a thieftaker by betraying to the authorities fellow criminals who ignored or resisted his own criminal organization.

(How did hundreds of antiquities end up in a London warehouse? These sleuths are on the case.)

Jonathan Wild

High stakes

Although there was big money to be made through robbery, the perpetrators were taking a considerable risk. In early 18th-century England, property-related crimes were punished more severely than those committed against people. In a society shaped by the rapid rise of the bourgeoisie, protecting property became imperative for the state. Judges did not think twice before handing down death sentences for simple theft.

Unlike Turpin and his ilk, Sheppard was no bandit. He did not hold up carriages or extort money by force. His avoidance of violence and choice of victims contributed to his folk hero status. He targeted members of the bourgeoisie, skillfully breaking into their houses through a mix of extraordinary physical agility and his talent for lock-picking. His first forays into crime were robbing the clients of the carpenter for whom he had worked as an apprentice. Having broken into their homes, he committed small-scale thefts, taking what he could carry— rolls of cloth, silverware, or coins.

Newgates' star prisoner

Legendary escapes

When Sheppard finally landed in jail, it was not because of clever police work but because of betrayal. The first to turn him in was his own brother, Thomas, who testified against Sheppard to save his own skin. Not long after that, Sheppard’s friend James Sykes followed suit, to claim a reward. In 1724, Sheppard was arrested and imprisoned five times, but managed to escape all but the final stint— earning instant fame and a place in the history books.

Fugitive couple

The first two breakouts were from minor prisons, but it was his third that would start turning Sheppard into a legend. This third escape, his first of two from Newgate, occurred during a visit from Lyon and a friend. The two distracted the guards, allowing Sheppard to escape disguised as a woman. Newspapers followed his exploits eagerly, casting him as a folk hero. A hefty reward was offered for information leading to his capture.

(The Tower of London has impressed—and terrified—people for nearly 1,000 years)

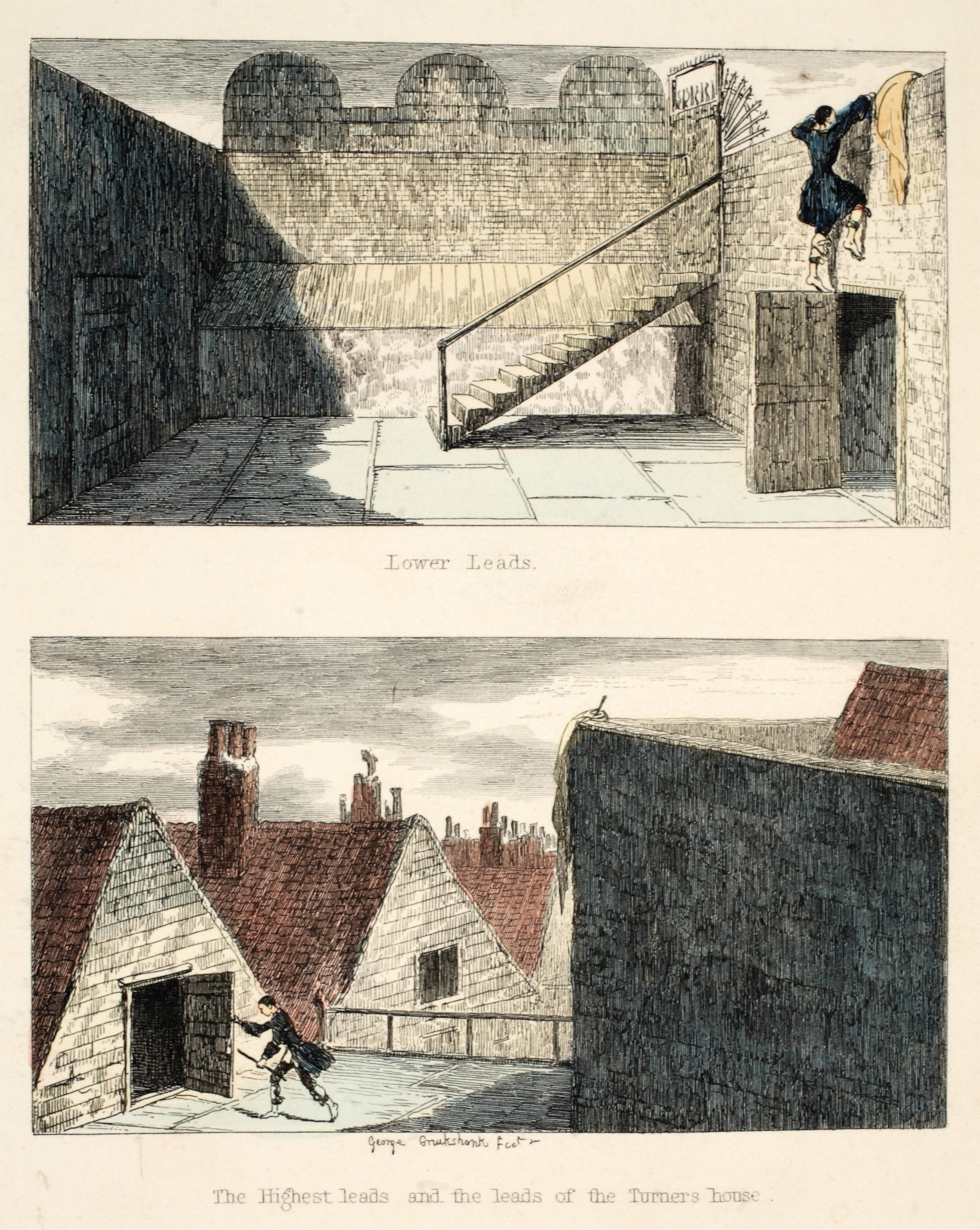

Sheppard was caught and returned to Newgate, locked away in the prison’s most impregnable room, known as the Castle. What happened next, on October 15, 1724, would go down in crime history. Chained to the floor, Sheppard somehow broke free and used a broken link from his shackles to smash through a section of the chimney, where a pipe blocked his only exit. Climbing up, he emerged in a room that had been sealed for seven years. Using skill and determination, he forced his way through the prison by unlocking, breaking, or prying open six barred doors before triumphantly gaining his freedom.

The gallows

No sooner was Sheppard free than he was back to flirting with risk. He stole again, and let himself be seen around the city dressed in finery. After a short time, he was recognized and arrested. This time, the guards took no chances. Shackled to the floor, he was watched day and night until November 16, 1724, when he was led to the public gallows at Tyburn amid much anticipation from the London public.

Sheppard embodied the spirit of freedom and escape until the very end, cracking jokes as the guards walked him to the noose. Although watching hangings was a part of daily life in London, Sheppard’s execution was especially spectacular, drawing the biggest crowd in 75 years. Sheppard’s charm and popular reputation for perpetrating what many saw as victimless crimes, as well as his escapology, made him a working-class hero. His admirers regarded him as a kind of wayward boy, guilty only of defying the rigid judicial system of the time.

Sheppard’s posthumous reputation was already taking shape in the last moments of his life. At the execution, attendees could buy copies of his supposed autobiography, The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard, likely ghostwritten by Daniel Defoe, who had followed Sheppard’s exploits in the newspapers and presented him in a positive and humane light.

(This 19th-century London dandy caused a style revolution)

A literary hero

This romanticized image of Sheppard only grew stronger with time. In 1728, just four years after Sheppard’s death, poet and playwright John Gay lit up the stage with The Beggar’s Opera, a razor-sharp satire on the lives of thieves and prostitutes in London’s underbelly. It was a runaway success and, two centuries later, would be reimagined by Bertolt Brecht as The Threepenny Opera.

In 1839, William Harrison Ainsworth cemented Sheppard’s legend with his novel Jack Sheppard: A Romance, a sensational retelling that captivated Victorian readers. Ainsworth, known for turning out popular fiction about infamous outlaws like Dick Turpin, found his greatest success with Sheppard’s story. The serially published novel, which appeared in 1839 and 1840, sparked a wave of theatrical adaptations so influential—and potentially subversive—that authorities eventually banned any stage play using Sheppard’s name, fearing it might glorify crime and corrupt the masses.

Like his contemporary Charles Dickens, Ainsworth had a keen eye for the struggles of the British working class in the wake of the industrial revolution. In his hands, Jack Sheppard was not just a thief—he became a rebellious symbol of society’s downtrodden fight against a brutal and unequal world.