The Tower of London has impressed—and terrified—people for nearly 1,000 years

Built to impress and terrify, the Tower was first a fortress in the 1070s and then evolved into a prison for enemies of the crown, including Anne Boleyn, the Nine Days' Queen, and Guy Fawkes.

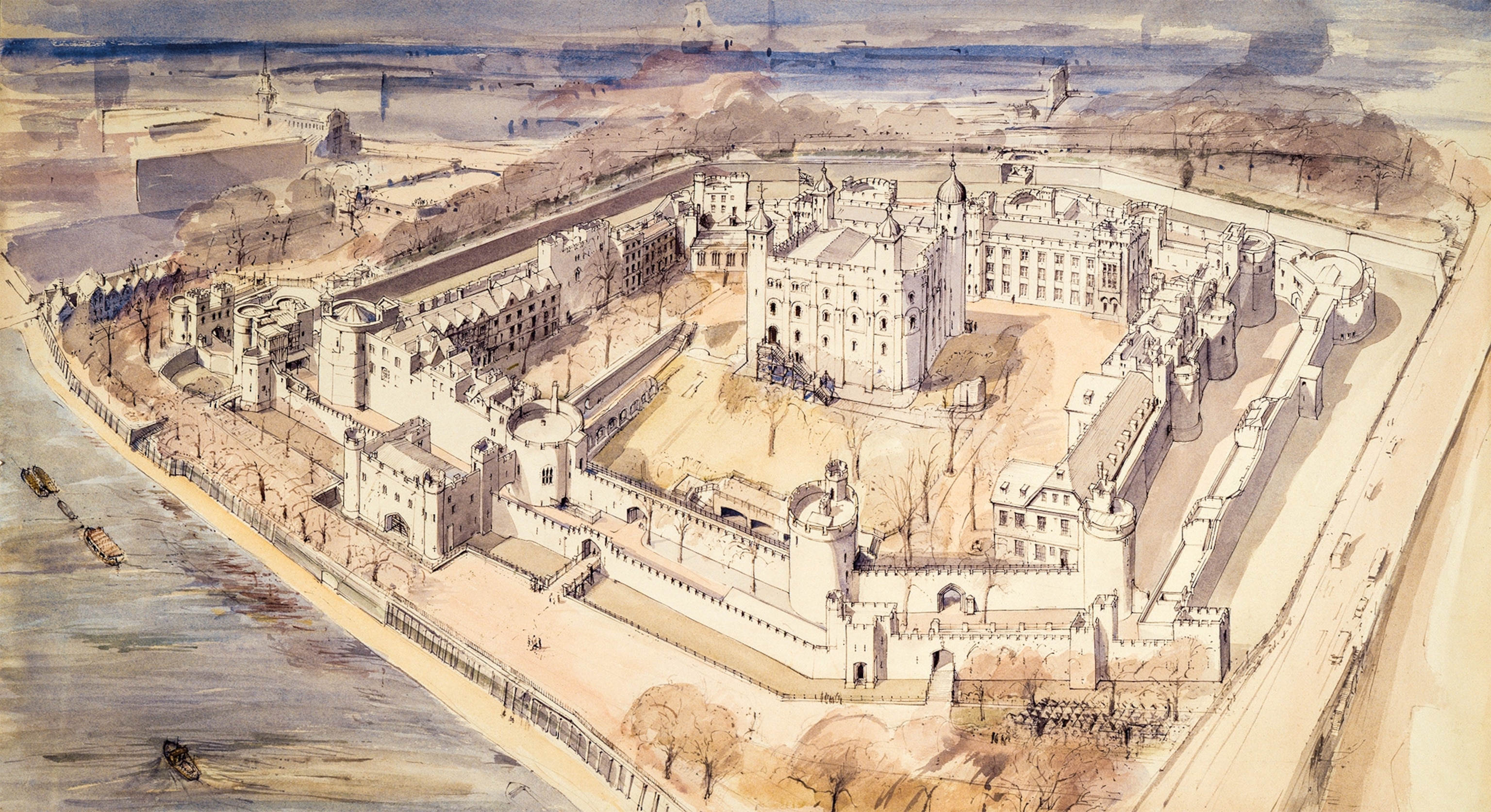

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London: How aptly the title states the major roles of this iconic structure. Rising next to the River Thames, it was once the largest nonecclesiastical building in England and a focus of power for each new monarch.

Over the centuries, the structure has been renovated, enlarged, and enhanced. As the architecture has changed, so has the Tower’s purpose. It’s been a fortress, a prison, and a palace. It’s served as the Royal Mint, displayed a menagerie of exotic animals, housed the crown jewels, and become the home of the six royal ravens, whose presence, tradition says, keeps the kingdom from falling.

(Queen Elizabeth II: A lifetime of devotion and service.)

Fortress on the Thames

The Tower of London’s origins go back to 1066. After defeating Harold II, last Saxon king of England, at the Battle of Hastings, William I of England (known as William the Conqueror) needed to consolidate his hold over his new kingdom. He doled out responsibility for conquered lands to his favorite nobles, a successful practice from wars in Normandy and elsewhere: they would build motte-and-bailey forts. A ditch was dug in a strategically appropriate spot, with dirt piled up to make or add to a hill (the motte). On top, soldiers erected a wooden tower or barracks, housing not only the fort’s battalion, but weapons, horses, food, and valuables. This barracks became a refuge if outer defenses were breached.

William the Conquerer used this tapestry as his war propaganda.

Around the hill, just inside the ditch, soldiers erected a palisade. The area within it (the bailey) had room for sinking a water well, raising a few crops, feeding livestock, practicing combat, and maintaining weapons. The Normans became so adept at this that they could build one in a week.

Twelve years after Hastings, William I wanted something more impressive to stake his claim to Saxon lands and intimidate hostile subjects. His fort, at a bend of the Thames just outside the London city limits, would become a castle. Gundulf, a clergyman adept at designing castles and churches in France, was installed as Bishop of Rochester in 1077, and then charged by William with designing the new fortress-castle.

(Anglo-Saxon England's defeat unfolds across the Bayeux Tapestry.)

It would become known as the White Tower (although it was not whitewashed until the 1200s). Nearly square, 107 feet by 118 feet and nearly 90 feet high, with 15-foot-thick walls tapering to 10 feet, the Tower did not so much rise as thrust itself up, visible from nearly every part of London and from several miles away. It had three floors: the cellar was used for storage. The first floor served many different purposes. There were living quarters, a large refectory for soldiers’ meals and entertainment, a small dormitory, and the beautiful Romanesque Chapel of St. John. The second floor’s three rooms were for the constable, the Tower’s commander: a great hall for banquets or other state occasions, the chapel gallery, and one space for bedroom, meeting room, and living quarters. Others who might also use this space included the king, important guests, or state prisoners.

The Tower took 20 years to build, and William did not live to see it completed. No sooner was it finished than Gundulf began a stone curtain-wall enclosing land between the Tower and the Thames, the first among many renovations. After changes by Henry III (r. 1216-1272) and Edward I (r. 1272-1307), the Tower and its “Liberties” assumed today’s basic design: the central White Tower, surrounded by two curtain walls (Gundulf’s earliest, innermost wall has long since disappeared), with their 20 towers and a wide grassy strip sweeping around the site’s three sides that are not bordered by the river.

English royals began using the site as a residence after a sumptuous palace was built between the southerly wall of the Tower and Gundulf’s curtain wall. Built and embellished by Henry III and Edward I in the 1200s, this palace became a residence of convenience (Edward staying only 53 days in his 35-year reign) or necessity, if a king needed refuge from enemies or an aroused populace.

By the 1500s the Tower Palace was no longer a home. Henry VII abandoned it after losing his firstborn son, Arthur. Perhaps his most enduring contribution to the Tower was founding the Yeomen of the Guard, direct ancestors of the Yeoman Warders, current caretakers and guides. Instead, the site would take on the function that would give it such notoriety in British history: a prison.

(London's underground treasures reveal lifestyles of the rich and English.)

Royal prisoners

The 1500s were not the first time the Tower of London had held prisoners. Two of the Tower’s earliest captives were prisoners of state: John the Good, king of France, captured during the Battle of Poitiers in September 1356; and Charles, Duke of Orléans, captured at Agincourt in October 1415. The fate of two of the youngest English subjects would later become the center of a tragic mystery: the fate of the “Princes in the Tower.”

After King Edward IV died on April 9, 1483, his will named Richard, Duke of Gloucester, lord protector of his son and heir, the 12-year-old Edward. Gloucester had Edward and his nine-year-old brother, Richard, Duke of York, sent to the Tower in May and June, respectively, ostensibly to await the young king’s coronation as Edward V. But the young heir would never take the throne. Perhaps spurred on by Gloucester himself, Parliament declared the two princes illegitimate and then confirmed Gloucester as King Richard III on June 26, 1483.

The two young princes were never seen alive again. Many historians speculate that the two boys were murdered in the Tower during the summer of 1483. When skeletons of two children were discovered under a Tower stairway in 1674, they were believed to be those of Edward V and the Duke of York. In 1678 the remains were interred in Westminster Abbey in a monument designed by Christopher Wren.

Among the Tower’s most famous prisoners were those incarcerated by King Henry VIII. Thomas More found that it did not matter if he was once the king’s best friend and chancellor. When Henry sought to divorce Catherine of Aragon and separated from the Catholic Church, More refused to acknowledge the king as the supreme head of the Church of England and the end of his first marriage. More was dismissed from office, arrested, removed from his family and home, and imprisoned in the Tower. He was convicted of treason; and executed on Tower Hill, just outside the walls of the Tower of London, in July 1535.

Execution of Thomas More: Gallows humor

Queens in the Tower

Henry VIII’s other famous “guests” of the Tower of London included two of his wives. Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife, had borne him one daughter (the future Elizabeth I) but no sons, leading Henry to desire a new wife, Jane Seymour. He had Anne arrested for treason, held in the Tower, and executed there in May 1536. Henry’s fifth wife, Catherine Howard, was also held briefly at the Tower prior to her execution there for adultery in 1542.

(Who are the real queens of "Six"?)

The Tower saw plenty of use as a prison in the turbulent years following Henry’s death as Catholics and Protestants fought for control of England. The sickly nine-year-old son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, King Edward VI had been raised a Protestant. In 1553, at age 15, Edward and his advisers created his “Device for the Succession” in which he disinherited his Catholic half sister, Mary, and his Protestant half sister, Elizabeth. Instead, his crown would pass down through his aunt’s line to her granddaughter Jane Grey, a Protestant. But no one told 17-year-old Jane, who only discovered the situation three days after Edward’s death on July 6, 1553. She reluctantly accepted and was proclaimed queen on July 10.

What little support Queen Jane had, including that of her entire Privy Council, evaporated in just nine days. Henry VIII’s oldest child, the Catholic Mary, was chosen as the next monarch by the Privy Council. Jane—known to posterity as “the Nine Days' Queen”—was imprisoned in the Tower on July 19.

In September Parliament officially declared Mary the queen and Jane Grey a usurper. Her trial was delayed until November, but both guilty verdict and death sentence were quickly handed down. Although Queen Mary was reluctant to sign Jane’s death warrant, she was finally persuaded that Jane remained a threat. Jane Grey was beheaded on Tower Green on February 12, 1554.

Queen Mary’s fears about usurpers were not calmed by Jane’s execution. She imprisoned her younger half sister, Princess Elizabeth (the future Elizabeth I), whom Mary believed was the focus of nobles plotting against her. For two months in spring 1554, the 20-year-old Elizabeth was kept under house arrest in the Tower. She resided in the same quarters where her mother, Anne Boleyn, had lived before her death. For exercise she was allowed access to the rooftop, still named “Princess Elizabeth’s Walk.” Finding no evidence of treason, Queen Mary moved her from the Tower to house arrest elsewhere in England.

Mary died in November 1558, and Elizabeth took the throne. The new queen continued to use the Tower to hold enemies of the crown, as would her successors. From Walter Raleigh to Guy Fawkes, the high-profile prisoners and deaths at the Tower would burnish its notorious reputation for centuries.

Imposing icon

Today the Tower has become one of London’s most famous tourist attractions. Visitors can gaze upon the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, including the coronation regalia, which is worn only at a new monarch’s investiture, and the ceremonial regalia, worn for the State Opening of Parliament.

Another popular sight at the Tower are its most famous modern residents: the ravens. According to tradition, King Charles II (r. 1660-1685) claimed that “if ever the ravens leave the Tower, the kingdom will fall.” At least six ravens live at the Tower and are cared for by a Yeomen Warder, the Ravenmaster (who also clips the birds’ wings to prevent them from flying too far). Through World War I, then the relentless Nazi bombing of London during the Blitz of World War II, the ravens showed no sign of leaving.

(London’s big dig reveals amazing layers of history.)

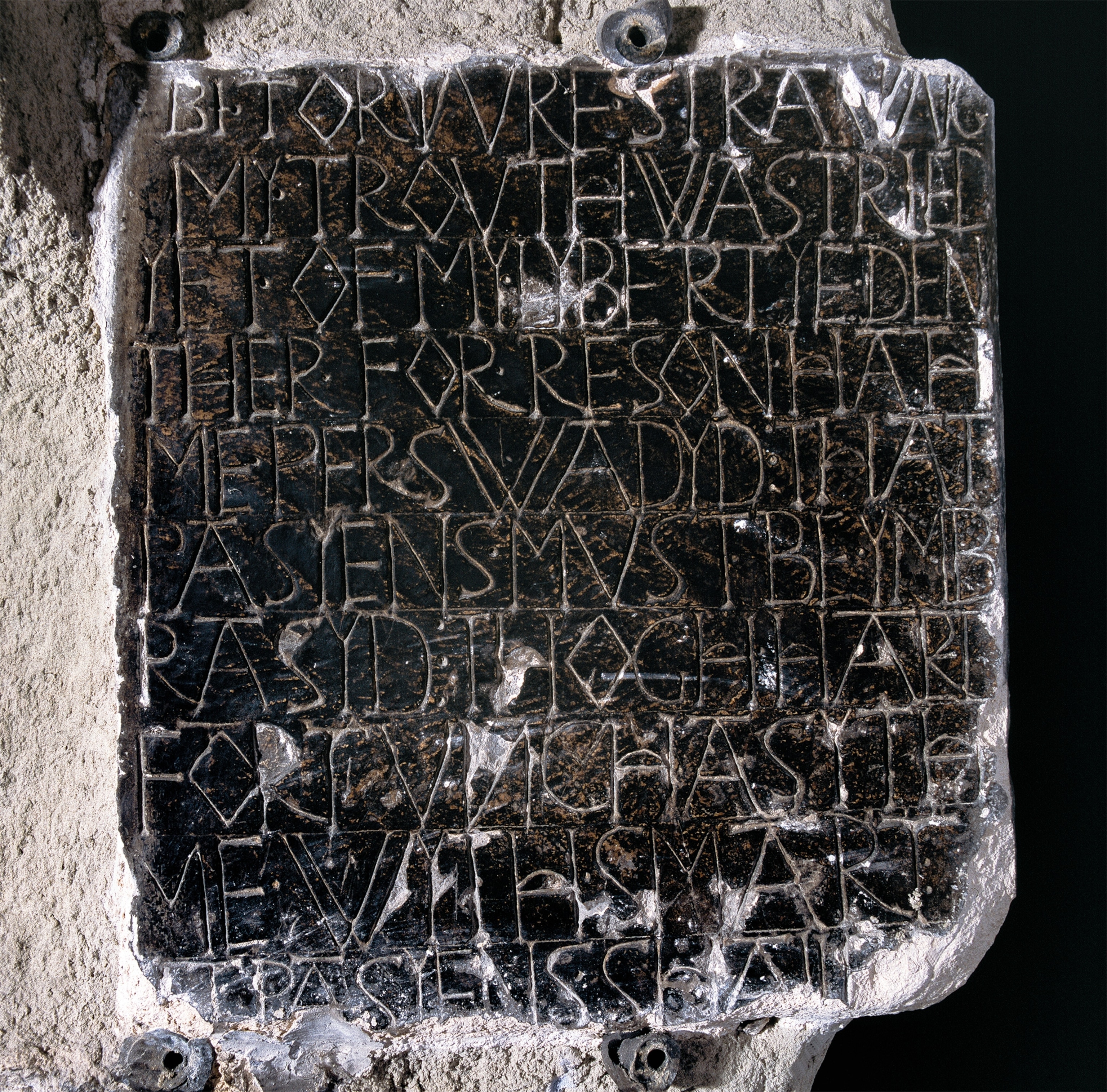

Any tour of the Tower cannot mention all the people whose histories form part of its nearly thousand-year legacy. Men and women, royal or commoner, foreigner or English citizen— those who were imprisoned there all played a part in the Tower of London’s story. Beyond the glittering jewels and the ebony ravens are humbler sites that can connect visitors with these people. In chambers like the Beauchamp Tower, prisoners carved graffiti into the walls, leaving behind their names, proclamations, and pictures—lasting memorials to their time in the Tower of London.