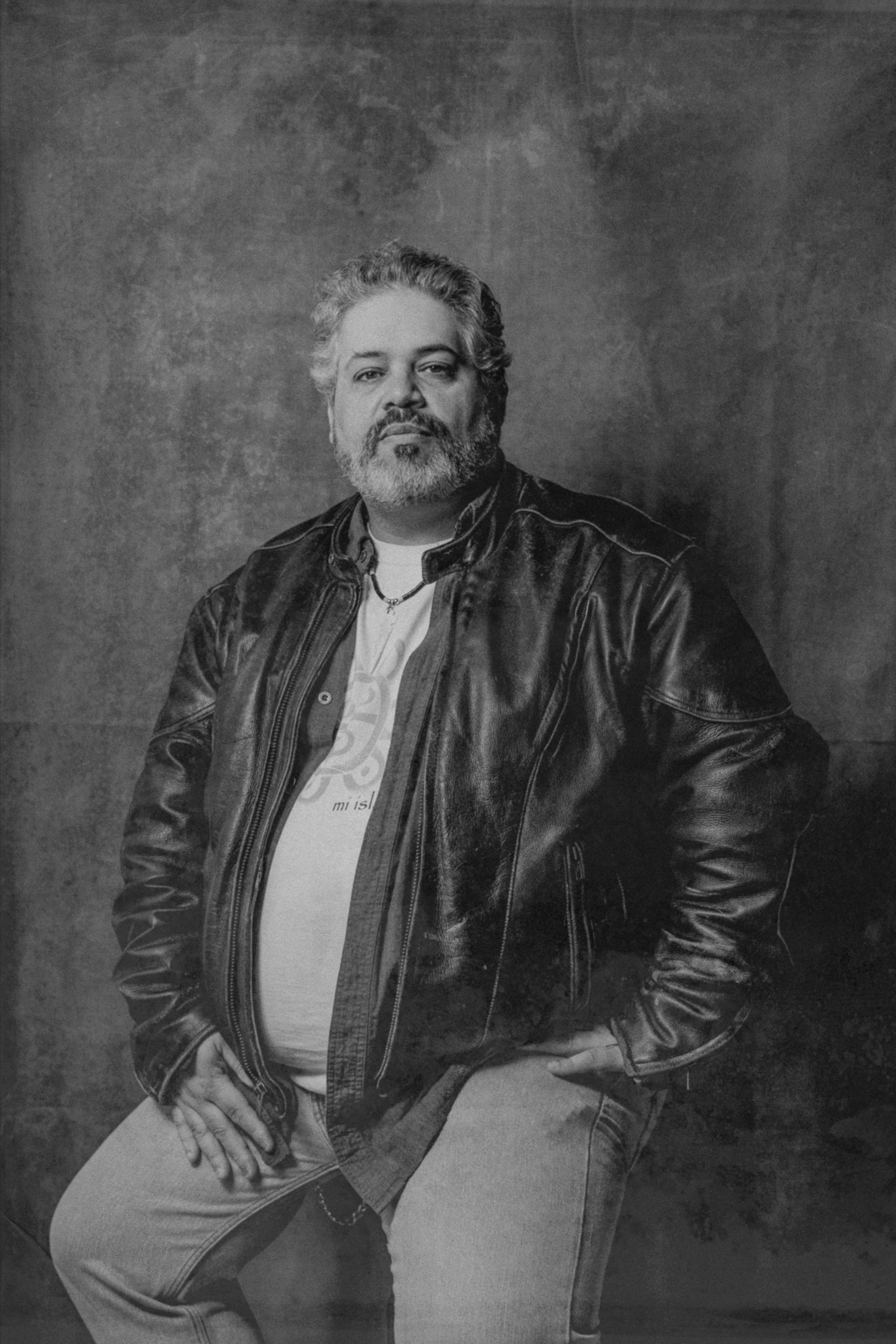

Meet the survivors of a ‘paper genocide’

A leader of the indigenous Caribbeans known as the Taíno describes how his people’s history was erased—and what they’re doing to get it back.

The people we now call Taíno discovered Christopher Columbus and the Spaniards. He did not discover us, as we were home and they were lost at sea when they landed on our shores. That’s how we look at it—but we go down in history as being discovered. The Taíno are the Arawakan-speaking peoples of the Caribbean who had arrived from South America over the course of 4,000 years. The Spanish had hoped to find gold and exotic spices when they landed in the Caribbean in 1492, but there was little gold and the spices were unfamiliar. Columbus then turned his attention to the next best commodity: the trafficking of slaves.

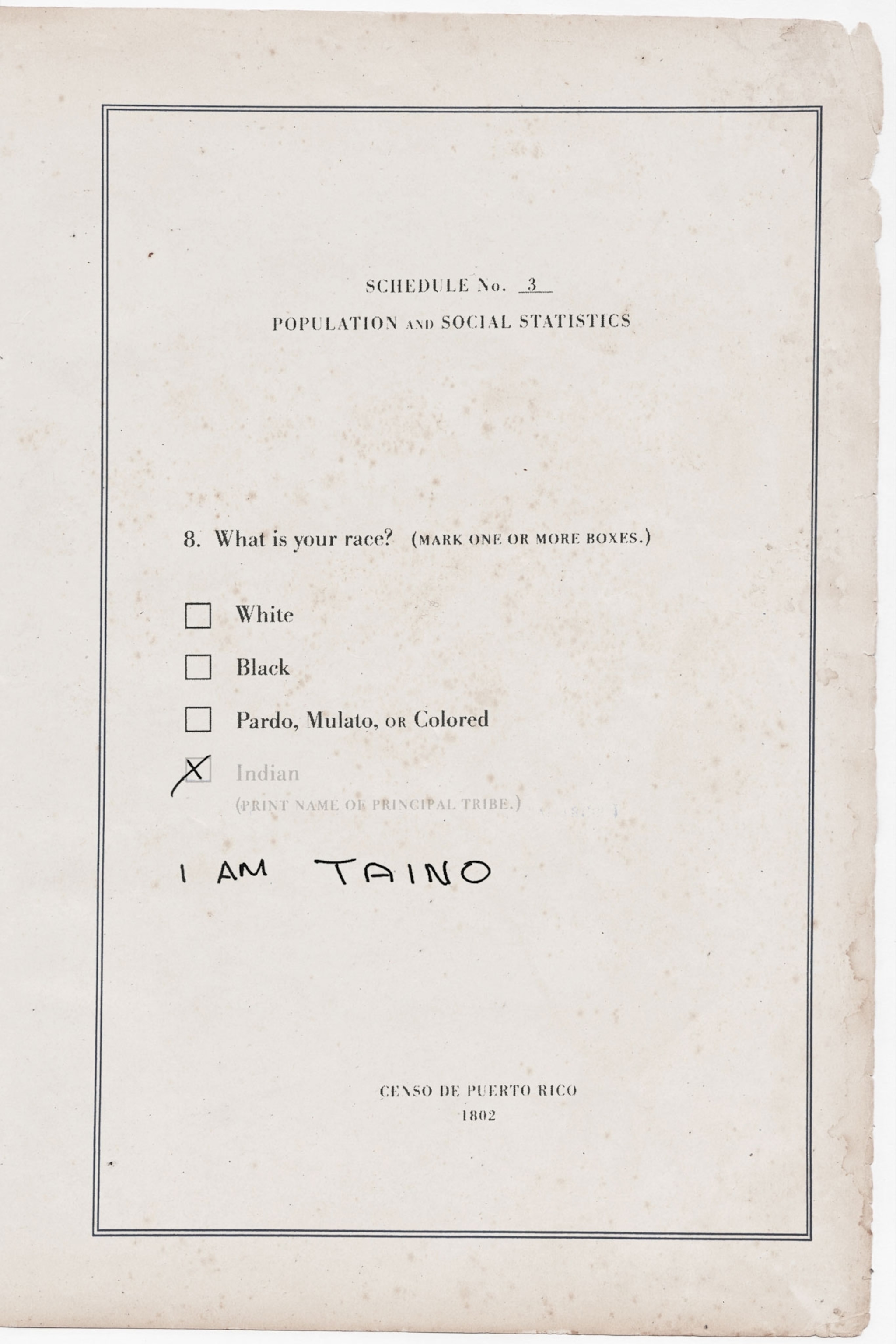

Due to harsh treatment in the gold mines, sugarcane fields, and unbridled diseases that arrived with the Spanish, the population rapidly declined. This is how the myth of Taíno extinction was born. The Taíno were declared extinct shortly after 1565 when a census shows just 200 Indians living on Hispaniola, now the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The census records and historical accounts are very clear: There were no Indians left in the Caribbean after 1802. So how can we be Taíno?

Few historians have taken a deep critical look at these census records, even though Indians kept appearing in reports, wills and testaments, and marriage and birth records throughout the Colonial period and beyond. We survived because many of our ancestors ran off into the mountains. When the inquisition began in Spain in 1478, any Jew that did not want to be tortured or murdered had only to convert to Catholicism. They became known as conversos (converts). This practice was also applied to Taíno Indians. Then, after 1533, when Indian slaves were “granted” their freedom by the Spanish monarchy, any Spaniard who was reluctant to let their Taíno slaves go would simply re-classify them as African. Throughout, Spanish men in the Caribbean were marrying Taíno women. Were their children not Taíno?

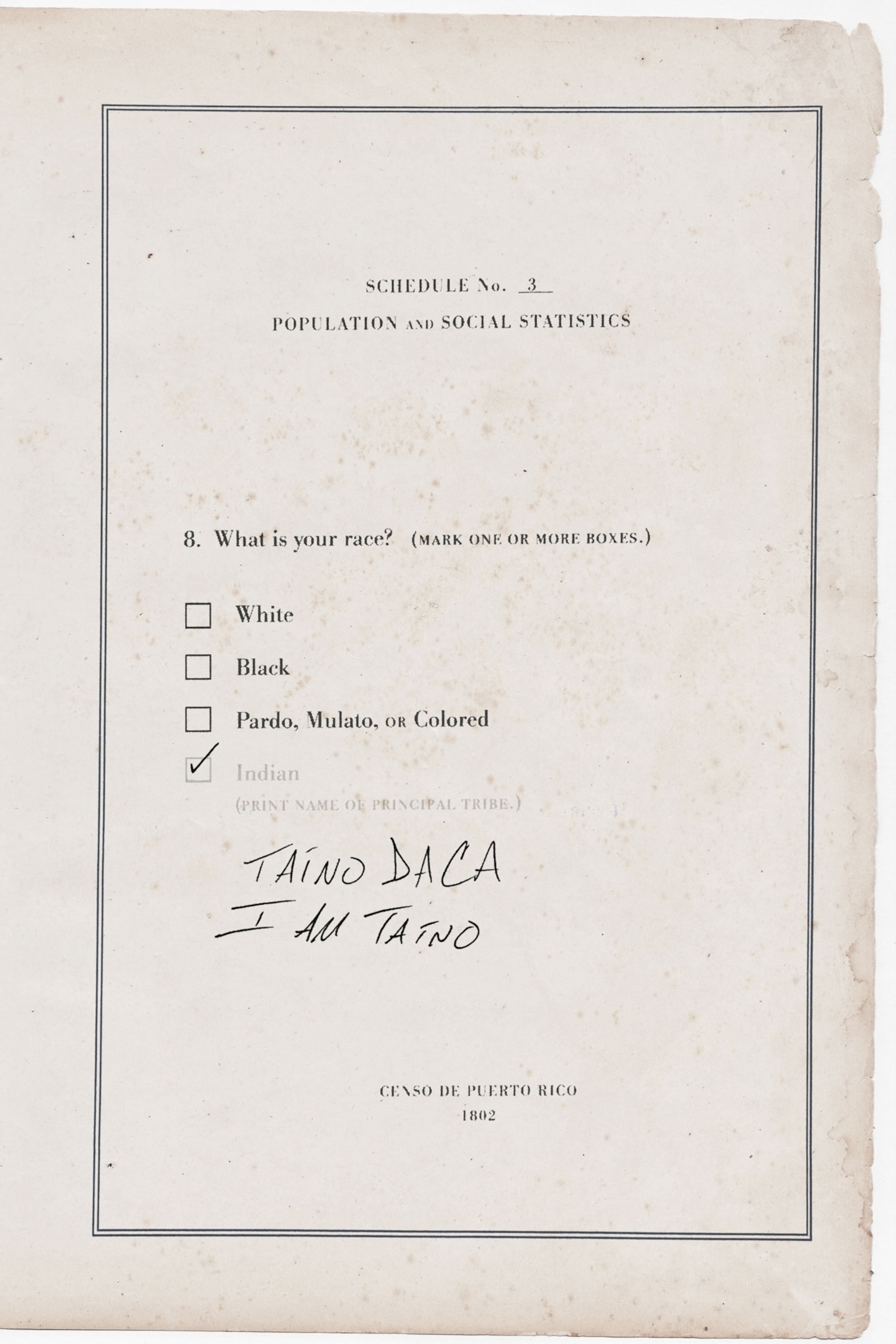

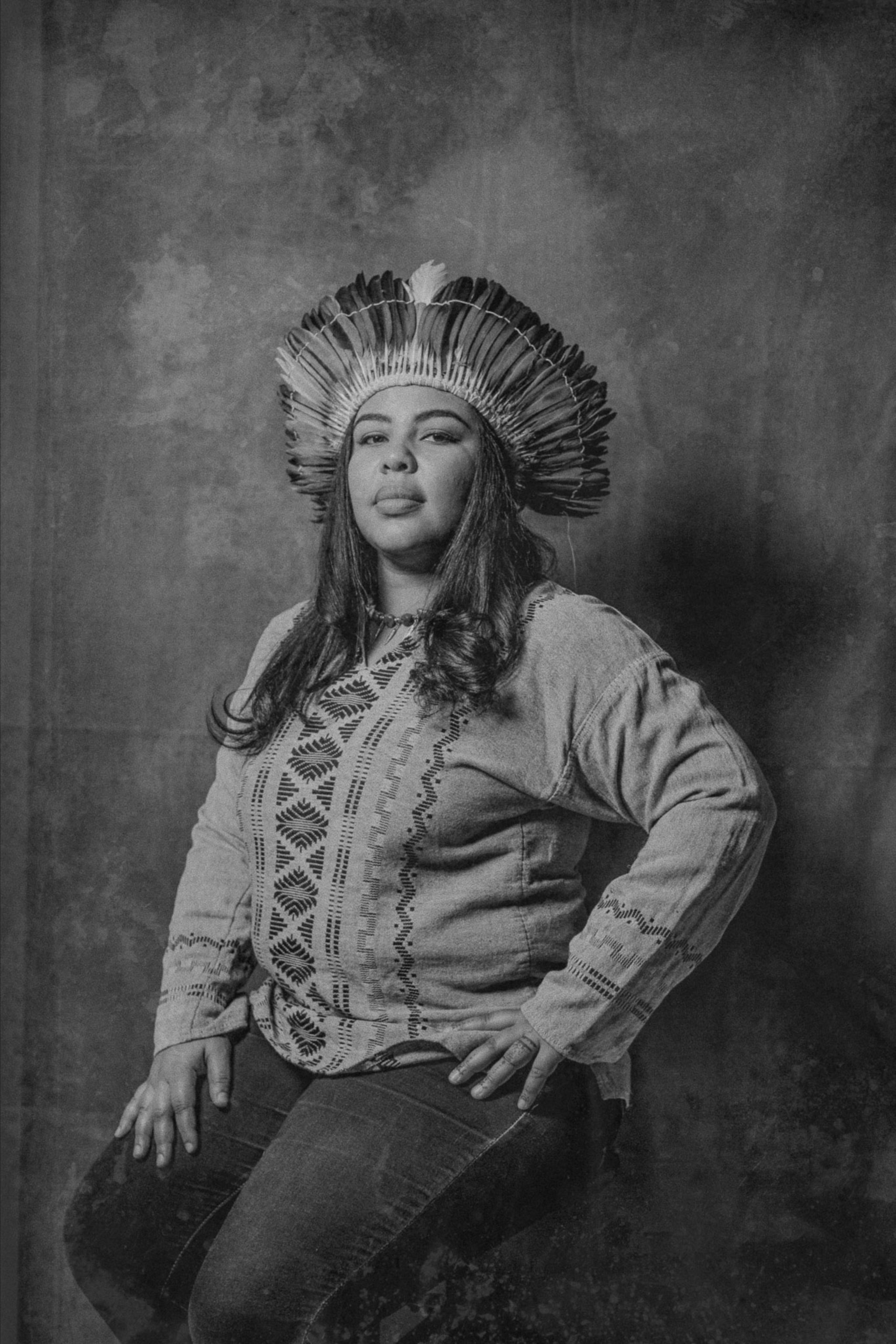

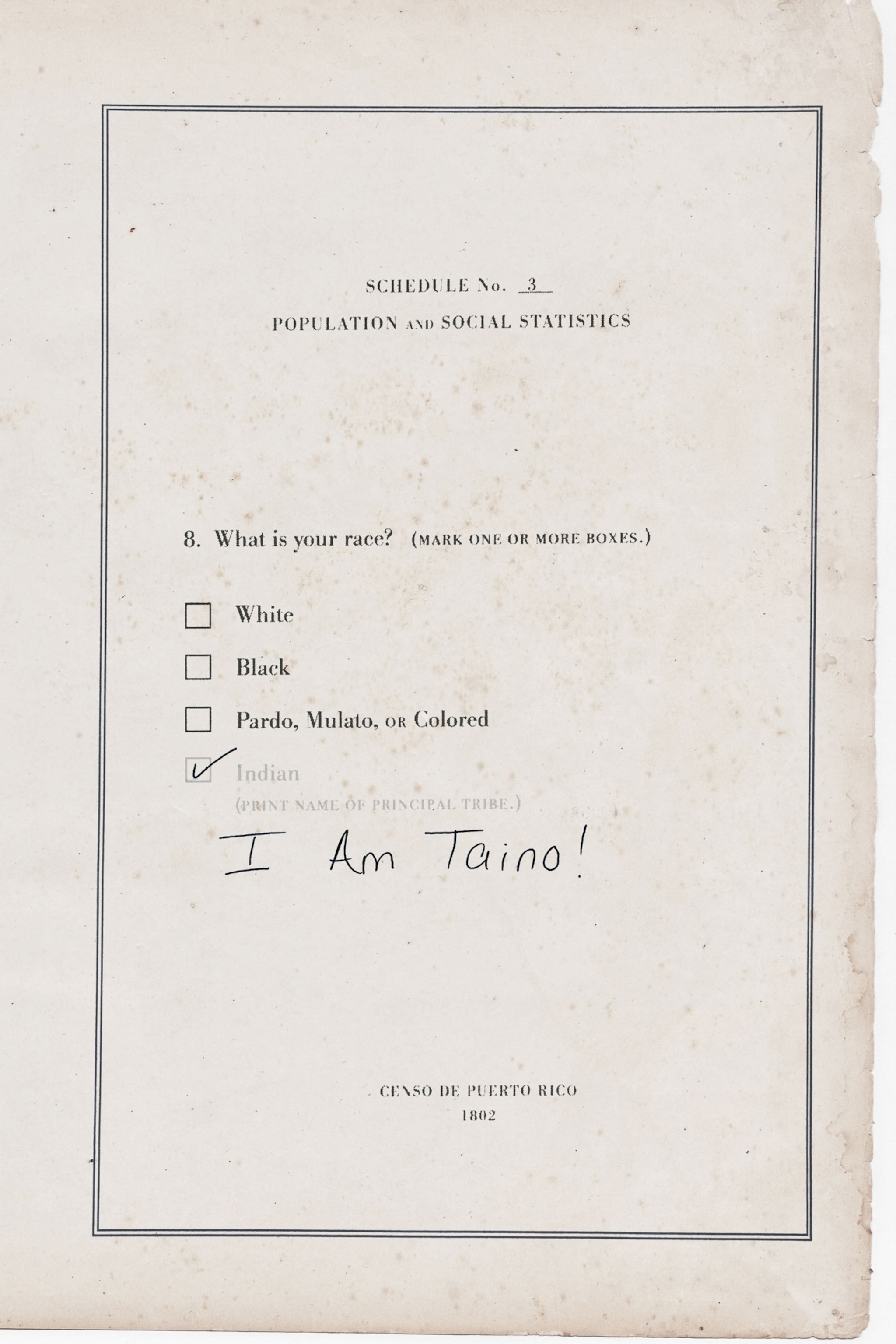

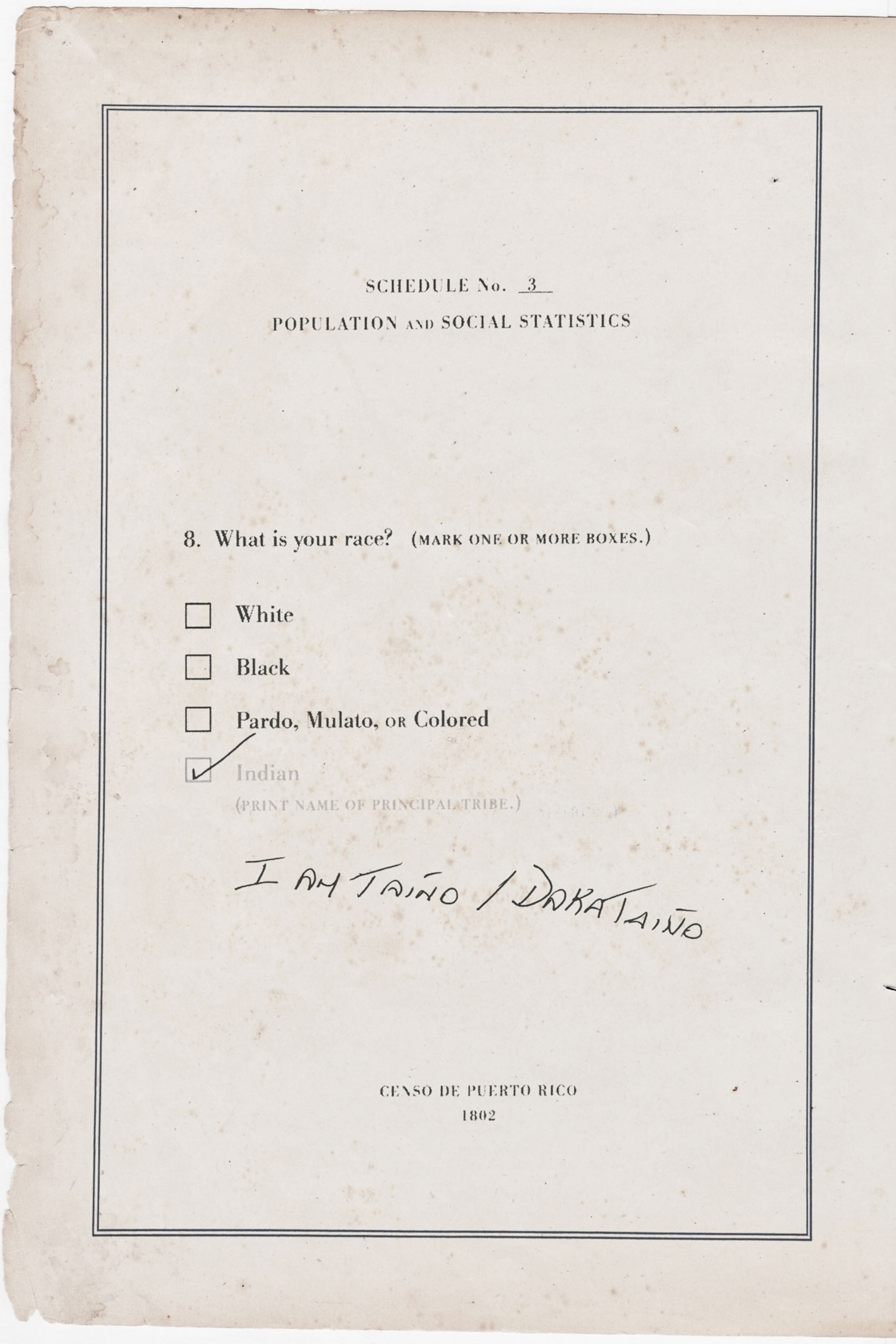

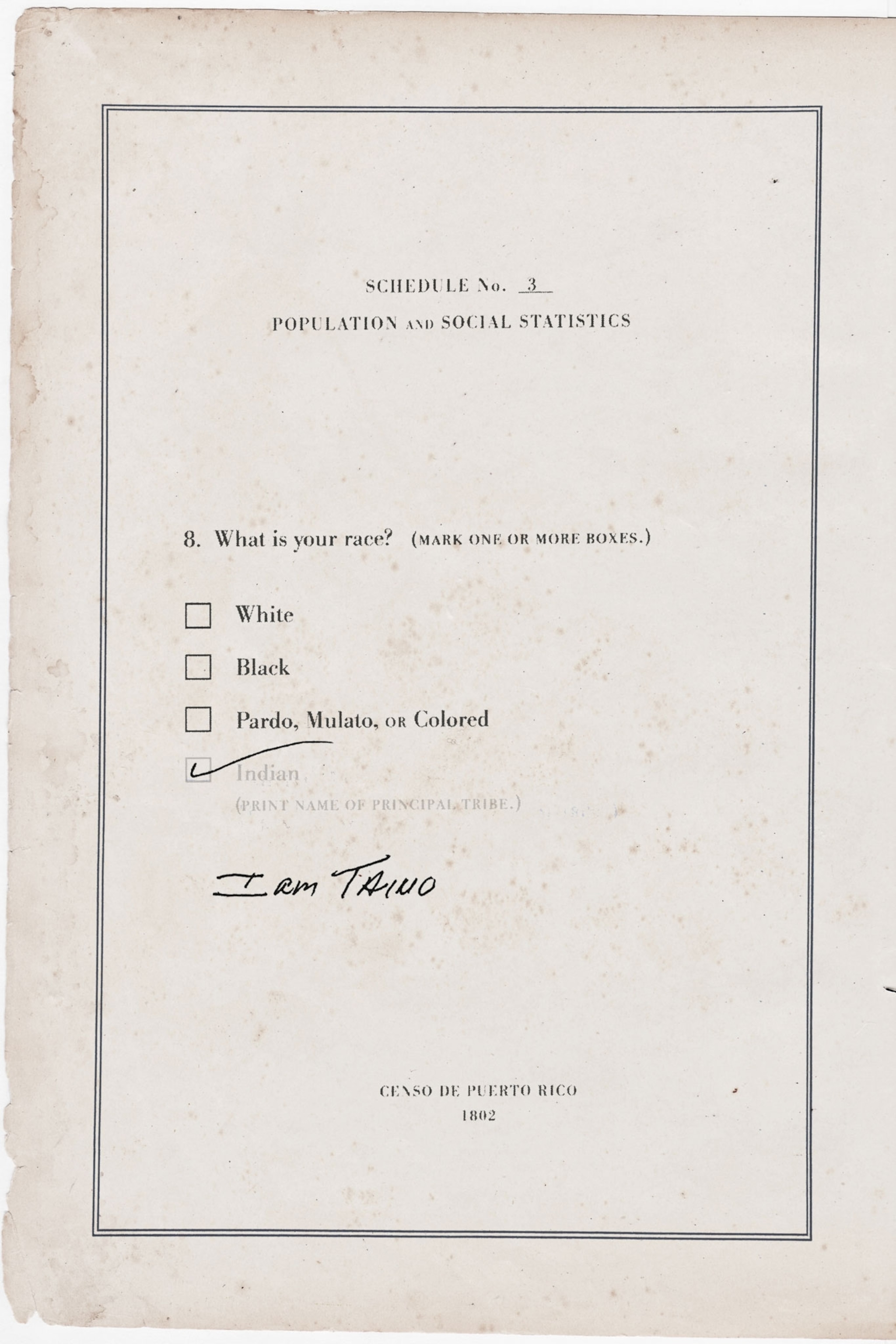

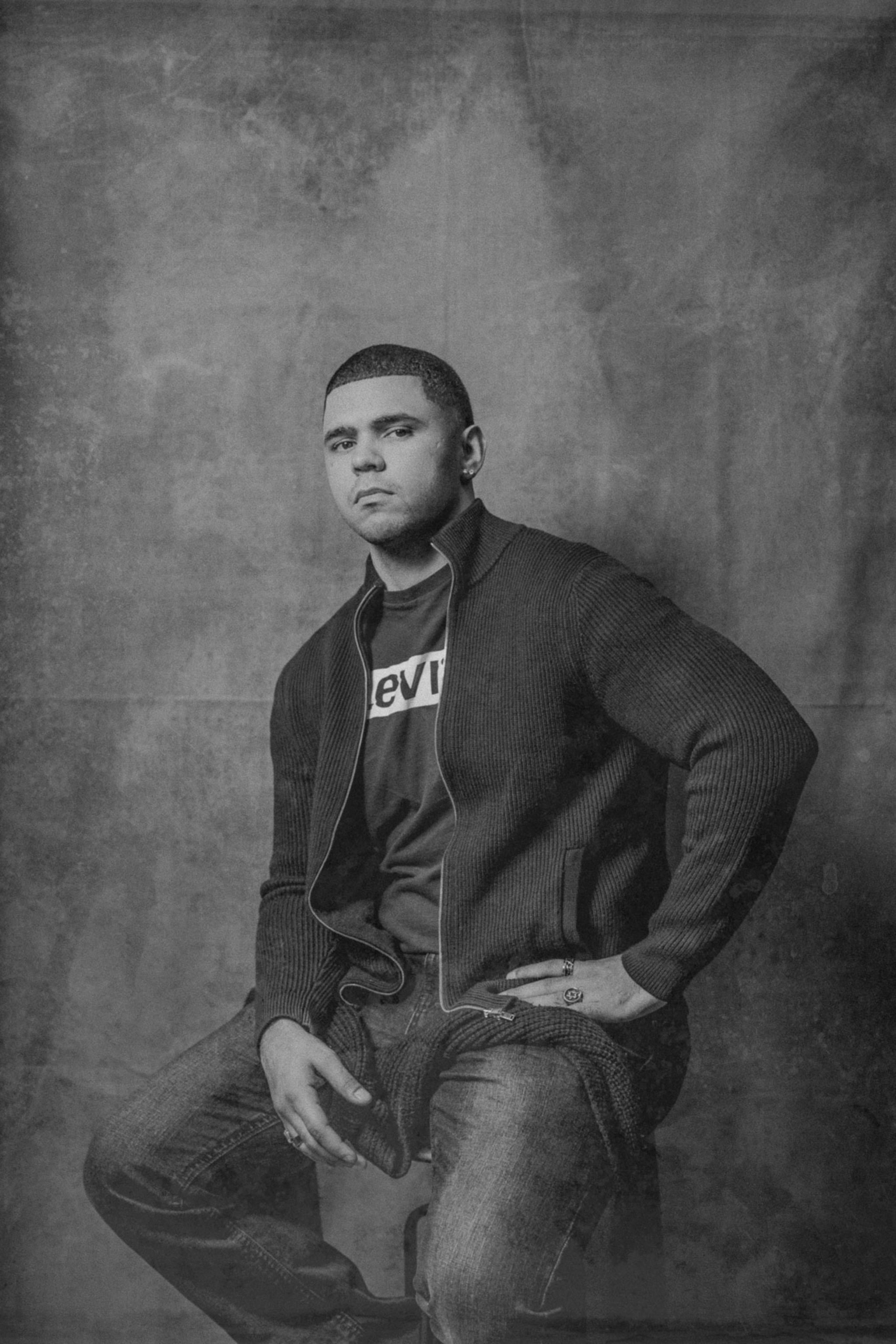

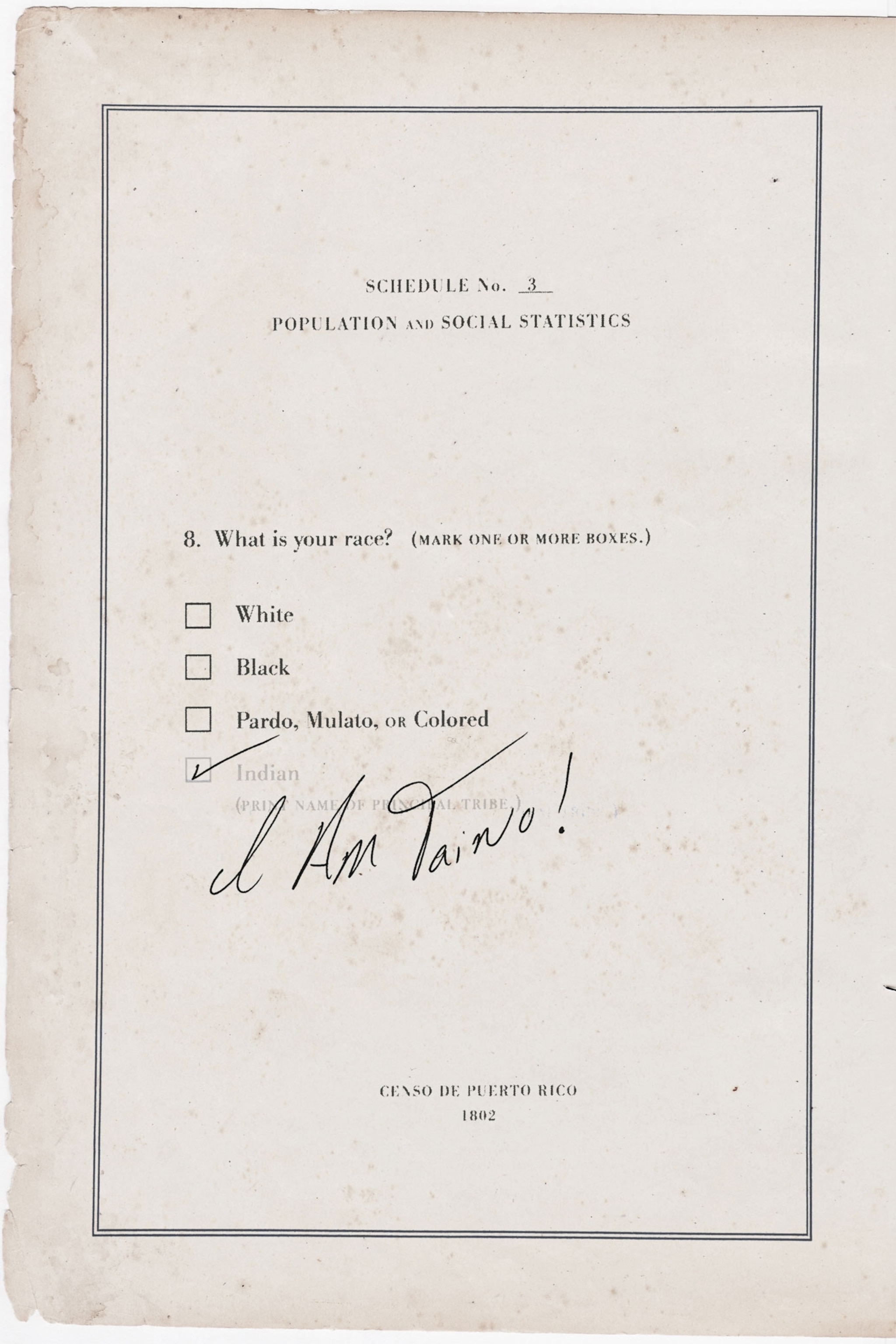

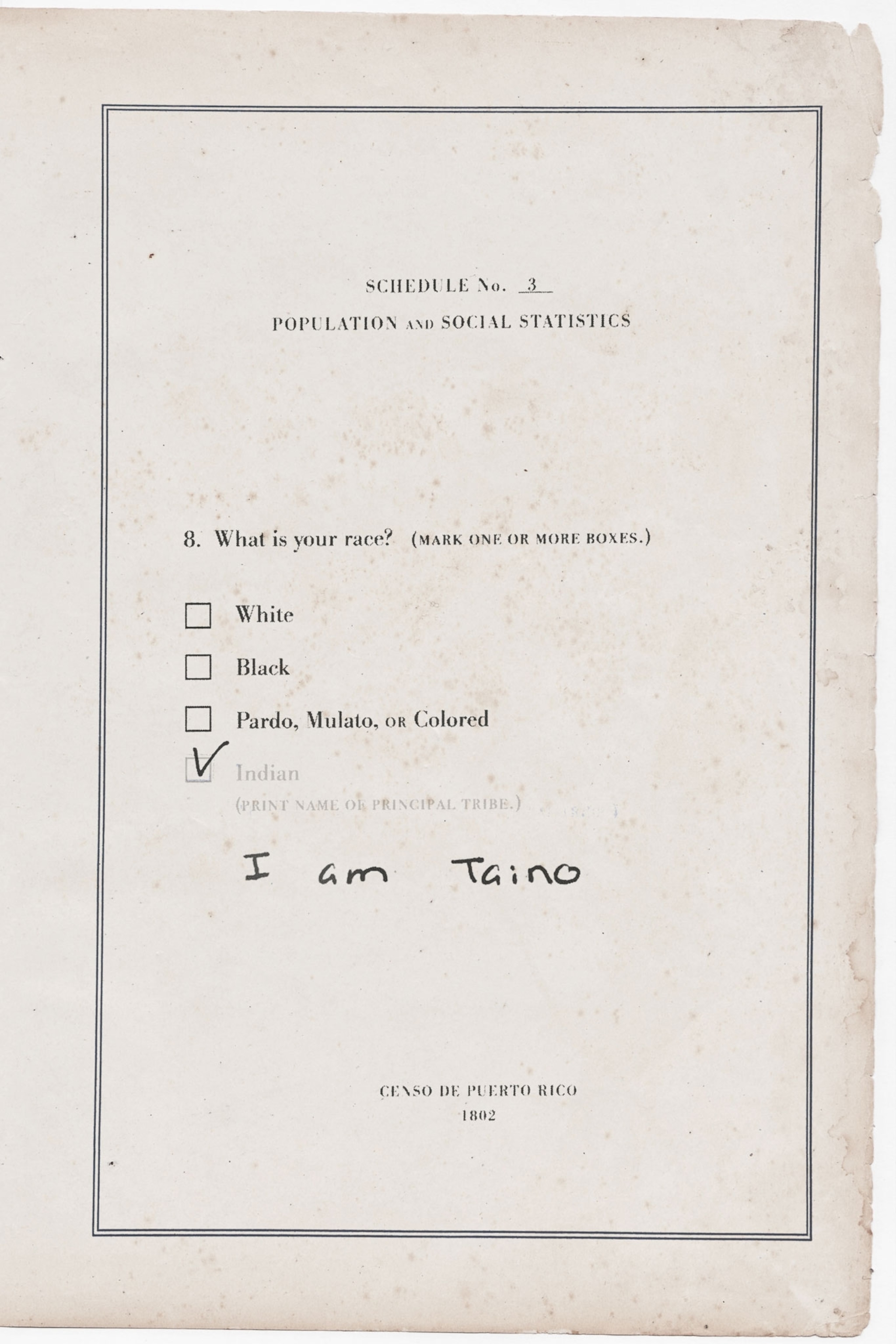

Paper genocide means that a people can be made to disappear on paper. The 1787 census in Puerto Rico lists 2,300 pure Indians in the population, but on the next census, in 1802, not a single Indian is listed. (The photography project here reimagines that census data.) Once something is put down on paper there is almost nothing you can do to change it. Every encyclopedia has Columbus’s accounts of his, and that he called us Indians and that not a single Indian was left in the Caribbean shortly after. No matter how you may look physically or assert your identity, you are extinct. This is paper genocide: a narrative created by the conquerors and perpetuated by every subsequent researcher.

I was born in the town of Jaibon in the Dominican Republic. As a young boy growing up in the United States, I had read that there was not a single drop of indigenous blood in the Caribbean, that every single Indian had been killed off. But people like myself always identified as indigenous. We always knew we had Indian ancestry.

In the early ‘90s we began meeting up at different native events such as pow-wows and festivals. We began a reclamation movement to try to preserve what we knew of the language and surviving practices.

Later DNA studies started to show that people in the Caribbean did indeed have Native American mitochondrial DNA: 61 percent of all Puerto Ricans, 23 to 30 percent of Dominicans and 33 percent of Cubans. That is a high number of genetic markers for a supposedly extinct people. In 2016, a Danish geneticist pulled ancient DNA from a tooth found in a 1,000-year-old skull from the Bahamas. This tooth had a full strand of Taíno DNA. Would we match? Of 164 Puerto Ricans tested, every single one matched the Taíno DNA. (Get the facts on whether DNA tests can reunite immigrant families.)

All along, we have been writing ourselves back into history. The internet is our most powerful tool. Today, we have a whole cadre of young scholars who identify as Taíno. Asking new questions and questioning old answers, they are writing us back into history. Some books have stopped using the word extinction to describe us as well.

Another way we assert our identity is by attacking the census records. For a long time, there was no Indian option for people from Latin America—you were either Hispanic, white, black, or a mixture. When the Indian or indigenous option was placed in the Puerto Rican census, 33,000 people identified as Indian. Our identities have always been hidden in plain sight. That’s what this photography project reflects.

We want the world to know that the Taíno people were not exterminated. We played an important role in the formation of our island nations. For us, learning this story is like finding a long lost relative, a piece of yourself that you knew nothing about. When I realized that much of our oral traditions, material culture, spirituality, and language is indigenous, I realized just how triumphant the Taíno people were. (Here's how mapmakers are helping indigenous people defend their lands.)

I remember when I first came home as a child after discovering Columbus. I was so excited and I’d drawn a picture of the three little ships. When I got home my mother told me the real story. I was shocked. Millions of people died because of his thirst for gold and recognition. To get to a point today where the population at large, not just Caribbean or indigenous people, agree that he’s not someone to be celebrated is very gratifying.

Whenever I contemplate my history and think of the atrocities committed by the Spaniards I wonder: What were the grandmothers and mothers doing as they watched their children, siblings, and parents slaughtered and raped, their villages pillaged and plundered? They must have prayed hard, as all suffering people do. But what happened to those prayers? Did they vanish in the air like smoke from a camp fire? Then it hits me: we the descendants are their prayers. We’ve come back to make things right, to tell our story.